Turning Community Colleges into Engines of Economic Mobility and Dynamism

Community colleges should be drivers of economic mobility, employment, and dynamism in local communities. Unlike four-year institutions, many of which are highly selective and pose significant barriers to entry, two-year colleges are intended to serve people from a wide range of life circumstances. In theory, they are highly egalitarian institutions that enable underserved individuals to access learning, jobs, and opportunities that would otherwise not be available to them.

However, community colleges are asked to do a lot of things with relatively little funding: they serve individuals ranging from highly gifted high school students to prospective transfers to four-year universities to people earning skilled trades certificates. This spreads schools’ attention broadly and is especially problematic given the wide range of non-academic challenges that many of their low-income students face, such as raising dependents and lack of access to reliable transportation. Troublingly, many community college degrees do not result in an economic return on investment (ROI) for their students, and many students will not recoup their investment within five years of completing a community college credential.

To address these issues, policymakers should reform community colleges in two essential ways. First, community colleges should align curricula toward fields with high wages and strong employer demand while increasing the amount of work-based learning. This shift would provide more job-ready graduates and improve student salaries and employment rates, thereby increasing student ROI. Second, the federal government should provide greater financial assistance in the form of Pell Grants and funding for wraparound services such as transportation vouchers and textbooks, allowing more students to access high-quality community college programs and graduate on time. These are interventions with a track record of proven success but require greater funding and support capacity to scale up at a national level.

Challenge and Opportunity

Challenge 1: Community colleges serve a wide range of students, including working parents seeking a better job, students who intend to transfer to four-year universities, and high school students taking dual enrollment classes.

There is no such thing as a typical community college student. As part of the Aspen Prize for Community College Excellence, the Aspen Institute collected demographic and outcomes data for its top 150 community colleges. Within this group, over 30% of students are “nontraditional” students over the age of 25, and 45% are minorities. Moreover, 63% of community college students attend part-time, which poses significant challenges in terms of scheduling and momentum. This severely impacts retention, graduation, and transfer rates. By contrast, just 11% of students at four-year flagship institutions are enrolled part-time. Community colleges must juggle these competing priorities and must do so in the absence of clear guidelines and insufficient resources.

Challenge 2: Underprivileged students tend to struggle the most given their financial constraints and insufficient access to wraparound services. At the same time, community colleges are already starved for resources and may not have the capacity to provide those critical services to these students.

Community college students are more likely than their four-year counterparts to come from less wealthy backgrounds. As of 2016, 16% of students in four-year colleges come from impoverished families, with another 17% coming from families near poverty. By contrast, some 23% of dependent community college students and 47% of independent students come from families with less than $20,000 of annual income. Unsurprisingly, two-thirds of community college students work, with roughly one-third working full-time.

Community colleges will be hard-pressed to cover students’ financial shortfalls from their own budgets. On average, community colleges receive $8,700 per full-time equivalent student versus $17,500 per student for four-year colleges (this overstates funding per enrolled student, because more community college students are enrolled part-time). Moreover, over half of community college funding comes from local and state sources. As a result, schools with the highest proportion of low-income students are more likely to have lower funding.

Challenge 3: The United States needs more nurses and allied healthcare workers, IT and cyber professionals, and skilled tradespeople, but the recruiting pipeline and training pathway for these individuals is often understaffed, highly fragmented, and hyperlocal.

Many industries with high-paying wages have experienced or will soon experience major talent shortages in the next decade. For instance, by 2030 the United States will need another 275,000 registered nurses, which, at the minimum, requires an associate’s degree in nursing (ADN) to sit for the NCLEX entrance exam. The country needs another 350,000 cybersecurity professionals, especially in the federal workforce, where 50% of the workforce is over the age of 50 and approaching retirement age. Finally, and certainly not least, the distributed renewable energy grid will not build itself: 30% of union electricians are between the ages of 50 and 70, and we will need more solar installers, wind technicians, and other skilled trades specialists to enable the green transition.

However, these issues are not easily solved by digitally native solutions rolled out at a national level. Instead, these need to be tackled at a local level. For instance, access to clinical space can only happen through hospitals, while skill development for electricians, installers, and technicians primarily occurs through high school and community college CTE classes and industry-led apprenticeships, all of which require a substantial in-person component. Thus, workforce training to fill shortages will have to be similarly local in nature.

Challenge 4: The value of the two-year associate’s degree and certificates is highly variable and depends on the type of degree or certificate earned.

The Burning Glass Institute studied the career histories of nearly 5 million individuals who graduated between 2010 and 2020 and built a rich dataset that tied salary information to LinkedIn profiles. They then assessed “degree optional” roles (jobs where 50% to 80% of individuals held a degree) and found that a four-year degree provided a 15% wage premium, which was largely driven by the job flexibility provided by the bachelor’s degree. By comparison, they found no such premium for two-year associate’s degrees.

However, these averages hide the economic variance provided by individual degrees. Third Way investigated the economic payback period for graduates of different degree programs, which they defined as the pay increase over the median high school graduate divided by the net tuition cost. Highly technical engineering, healthcare, and computer science associate’s degrees provided exceptional payback periods, with more than 90% recouping their investment in less than five years.

By contrast, other associate’s degrees saw no economic ROI. Some of these degrees, such as general humanities and culinary arts, are unsurprising. However, other fields, such as biological and physical sciences, for which half of students had no ROI, might have had stronger ROIs as bachelor’s degrees.

Similarly, certificate programs have wildly varying ROIs. Nursing and diagnostic and skilled trades generally show a strong ROI, with more than 85% of students recouping their investment within five years. On the other hand, cosmetology, culinary arts, and administrative services are highly likely to receive no ROI, indicative of the low pay in the roles that certificate earners take upon completion of their program.

Together, these studies show that associate’s degree programs and certificates with less-defined career pathways are at risk of value erosion. This may be due in part to real differences in the skills taught in a two-year degree or certificate versus a four-year program. However, it is also clear that highly technical associate’s degrees and certificates designed to meet employer-defined needs have better economic ROIs, suggesting that there is less value erosion in roles with well-defined pathways.

Plan of Action

To address these issues, policymakers, community college leaders, employers, and philanthropic stakeholders should work together to implement five general reforms:

- Reorient community college offerings toward technical associate’s degrees and certificates that have been shown to have a strong, locally proven ROI for students while pruning programs that do not have compelling outcomes. The federal government should allocate funding to programs that have compelling five-year repayment rates and fill jobs that have high and persistent skills shortages. In addition, the Department of Education can write a “Dear Colleague Letter” that focuses on program ROI and suggest that Congress pass laws strengthening ROI requirements for federal funding

- Community colleges and local employers should partner to deliver more job training at scale, including apprenticeships and skills-based part-time work. Many of these programs, such as Project Quest, have been established for years, and community colleges can and should play a bigger role in building a student pipeline and delivering in-classroom training that leads to a high-quality credential. In addition, under the Inflation Reduction Act, local employers can receive tax breaks for clean energy projects that use registered apprenticeships. These apprenticeships, which supplement on-the-job training with classroom instruction and are tailored to employer needs, can be provided by community colleges

- Increase Pell Grant maximums to improve degree affordability and access. For the upcoming 2023–2024 school year, the maximum could be raised by $500, in line with the 2024 President’s Budget. Congress should enact provisions in the president’s budget that would provide $500 million in funding for community college programs that lead to high-paying jobs and $100 million for workforce training, both of which would strengthen post completion outcomes. In addition, Congress should pass legislation that makes Pell Grants nontaxable, which would enable students to use funding on living expenses.

- Develop and fund high-ROI wraparound solutions that have been shown to improve student outcomes, such as those developed by the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP). These include career guidance, textbook assistance, and transportation vouchers, among others. The Department of Education should also allow community colleges to spend funding (for example, some of the increases proposed in the president’s budget) on supports that are not already covered by existing entitlement programs. In addition, state and local governments can earmark special taxes and work closely with philanthropic funders to experiment with and deploy wrap around solutions, helping policymakers further assess the most cost-effective interventions.

- Create comprehensive data tracking mechanisms that track data at state and local levels to evaluate student outcomes and relentlessly funnel public, private, and philanthropic capital toward interventions and degree programs that are shown to result in strong outcomes. In particular, the recommendations in the bipartisan College Transparency Act are a good start given that they would tie Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data together.

Recommendation 1. Community colleges should reorient their offerings toward degrees that provide strong employment outcomes and student ROI (e.g., associate’s degrees in nursing and maintenance and installer certificates).

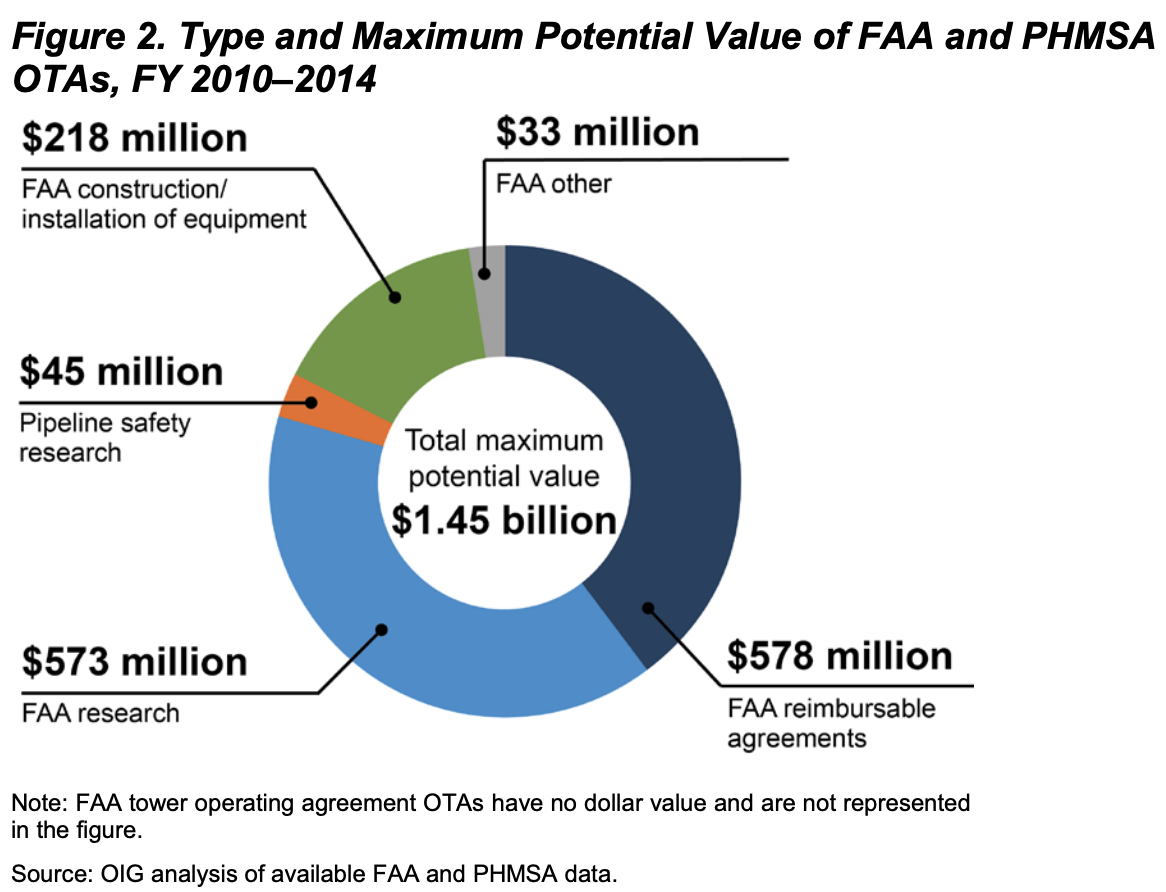

The data is unambiguous: Some programs deliver strong outcomes while others are drains of students’ and taxpayers’ money. Community colleges can better serve students by focusing more time and resources on the programs that deliver strong ROIs within their local economic contexts. As Figures 2– 4 show, these programs skew heavily toward nursing and allied health, engineering and computer science, and skilled trades roles. These also dovetail with major labor shortages, suggesting that community colleges can play a significant role in matching labor supply with demand.

This premise sounds deceptively simple but requires a meaningful reimagination of the role that community colleges play. By asking community colleges to refocus toward highly technical associate’s degrees and certificates, they would end up eschewing other aspects of the higher education landscape. In this view, community colleges would de-emphasize the production of liberal arts associate’s degrees. While they would continue to teach core science and humanities courses, the structure and content would be primarily geared toward equipping students with the critical thinking and foundational skills required to excel in higher-level technical courses. Community colleges would thus further increase their role in providing vocational training.

Refocusing community colleges on certain degrees would allow institutions to devote their limited resources to helping students navigate a smaller set of pathways. While it is certainly true that community colleges could improve liberal arts associate’s degree ROIs by helping students transfer to four-year universities, a greater emphasis on vocational degree production would help two-year colleges focus on their core competitive advantage in the higher education market. In the long run, greater focus would reduce administrative burden while helping professors, guidance counselors, and financial aid officers develop expertise in high-demand training and career pathways. In addition, a narrower focus on high-ROI degrees improves the effectiveness of public and philanthropic spending, making large-scale interventions more feasible from political and financial perspectives.

Recommendation 2. At the local level, community colleges should partner with employers to deliver job-specific training at scale (for example, apprenticeships or skills-based part-time work paired with associate’s degrees), helping economies match labor supply and demand while providing students with pay and relevant work experience.

Although increased tuition assistance would significantly improve financial access for many community college students, the reality is that programs such as the Pell Grant, while highly effective, still leave students with major financial gaps. As a result, many community college students end up working: as Figure 1 shows, 47% of independent community college students come from incomes of less than $20,000.

A practical approach would be to ask how we might optimize the value of hours worked rather than asking how we might avoid hours worked at all. Many community college students are employed in retail and other frontline roles: in fact, 23% of students in the Washington state dataset worked in retail at the start of their academic career, while another 19% worked in accommodation and food service. These are entry-level roles that pay low salaries, provide poor benefits, and are unlikely to teach transferable skills in high-paying professions.

A better way to provide wages as well as professionally transferable skills would be to increase funding for work-based training programs, including apprenticeships and part-time roles, that are directly related to the student’s course of study. The Department of Labor should fund a large increase in work-based training programs that provide the following characteristics:

- Are tied to an accredited course of study at a community college or other institution of higher learning with proven outcomes

- Are targeted toward roles and industries with job shortages, such as registered nurses

- Are designed in collaboration with employer partners who will ensure that students are learning skills directly related to their role and industry

- Have sufficient funding for key administrative and wraparound expenses, including career counseling and transportation stipends

Research has started to highlight the long-term benefits of well-designed work-based learning programs focused on high-paying jobs. San Antonio-based Project Quest works with individuals in healthcare, IT, and the skilled trades to provide low-income adults with credentials and employment pathways (sometimes through community colleges but also with trade schools and four-year universities providing certificates). In addition to training, Project Quest provides comprehensive wraparound support for its participants, including financial assistance for tuition, transportation, and books, as well as remedial instruction and career counseling.

In 2019, Project Quest published the results of its nine-year longitudinal study that included a randomized controlled trial of 410 adults, 88% of whom were female, enrolled in healthcare programs. Thus, replicability for other industries may prove challenging. Nonetheless, the study showed highly positive and statistically long-term earnings impacts for its participants, results that have not been easily replicated elsewhere.

Properly designed standalone apprenticeships have the potential to deliver large and positive impacts. For example, the Federation of Advanced Manufacturing Education (FAME) has long had an apprenticeship program in Kentucky to develop high-quality automotive manufacturing talent for skilled trades roles, which blends technical training for automotive manufacturing, skills that can be transferred to any industrial setting, and soft skills education. Participants complete an apprenticeship and finish with an associate’s degree in industrial maintenance technology. Within five years of graduation, FAME graduates had average incomes of almost $100,000.

The Inflation Reduction Act, Infrastructure Act, and CHIPS Act have made it clear that reinvesting in America’s industrial base is a key policy priority. At the same time, the private sector has identified major skill shortages in the skilled trades as well as healthcare and IT. Community college administrators can lead the effort to create work-based training solutions for these key roles and coordinate the efforts of various stakeholders, including the Departments of Education and Labor, state governments, and philanthropic organizations seeking to fund high-quality comprehensive solutions such as the ones developed by Project Quest. In doing so, community college leaders can move to the vanguard of outcomes-driven, ROI-based higher education.

Recommendation 3. The federal government should increase Pell Grant funding and ensure that more students receive funds for which they are eligible.

Pell Grants are an essential component of college funding for many low-income college students, without which higher education would be unaffordable. For the 2023–2024 school year, the Pell Grant maximum is $7,395, and on average students receive around $4,250. By contrast, the average tuition at a community college is just under $4,000, with the total cost of attendance at around $13,500. Thus, the average Pell Grant would cover all of tuition but just one-third of the total cost of attendance, assuming that the student was enrolled full-time. Nonetheless, Pell Grants are highly effective tools: the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond conducted a pilot study of 9,000 students and found that 64% of Pell recipients had graduated, transferred, or persisted in their program within 200% of the normal completion time, as opposed to 51% of non-Pell recipients.

Increasing Pell Grant awards will have two important effects. First, additional Pell Grant assistance reduces the out-of-pocket tuition burden, in turn increasing financial capacity for critical expenditures such as living expenses, textbooks, and transportation. Second, students who receive Pell Grant funding in excess of the tuition maximum could directly apply funds to those expenditures. However, under current IRS code, Pell Grant funding that is applied to living expenses is taxable. Congress should pass legislation that makes Pell Grants nontaxable in order to avoid penalizing students who use funds on critical expenses that might otherwise go unfilled or would require funding from an outside organization.

President Biden’s 2024 budget, which proposes a $500 increase in the maximum Pell Grant, is an excellent baseline for increasing access to high-quality community college programs. In all, this is estimated to cost $750 million in 2024 (including four-year college students), with a more ambitious pathway to doubling the grant by 2029. Moreover, the president’s budget calls for $500 million to start a discretionary fund that provides free two-year associate’s degree programs for high-quality degrees. These proposals have shown progress at the state level: for instance, Tennessee, a Republican-led state, offers free community or technical college to every high school graduate. Furthermore, tying funding to programs with strong graduation and salary outcomes ensures that funding flows to high-quality programs, improving student ROI and increasing its appeal to taxpayers.

Policymakers should also do more to ensure that students take advantage of funds they are eligible to receive. In 2018, the Wheelhouse Center for Community College Leadership and Research examined data from nearly 320,000 students in California. Over just one semester, they found that students failed to claim $130 million of Pell Grants they were eligible for. Sometimes, students simply forget to apply, but in other cases, financial aid offices put artificial obstacles in the way: half of financial aid officers report asking for additional verification beyond the student list required by the Department of Education. Community colleges should be given more resources to ensure that eligible students apply for grant funding, but financial aid offices can also help by reducing the administrative burden on students and themselves.

Recommendation 4. In addition to expanding Pell Grant uptake, the public sector should fund and distribute wraparound services for community college students focused on high-impact practices, including first-year experiences, guidance counseling and career support, and ancillary benefits, such as textbook vouchers and transportation passes.

In 2014, the Center for Community College Student Engagement assessed 12 community colleges to evaluate three essential outcomes: passing a developmental course in the first year, passing a gatekeeper course in the first year, and persistence in the degree program. They then pinpointed a set of practices that were meaningfully more likely to positively impact one or more of the target outcomes.

One successful intervention that bundles together many of these practices is the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP), developed in the City University of New York (CUNY) and eventually expanded to three Ohio community colleges. The ASAP study, a randomized control trial of 896 students at CUNY and 1,501 students in Ohio, provided tuition assistance and wraparound supports such as tutoring, career services, and textbook vouchers.

The program delivered outstanding results: 55% of CUNY students graduated with a two-year or four-year degree versus 44% of the control group. The Ohio results were even more compelling, with the ASAP program improving two-year graduation rates by 15.6% and four-year registrations by 5.7% at a 0.01 significance level.

To scale these programs, the federal government should allow grants to be used for wraparound supports with strong research-based impacts, potentially drawing from (or in addition to) the $500 million community college discretionary fund in the president’s budget. Ideally, this would be done via competitive applications with an emphasis on programs that target disadvantaged communities and focus on high-quality degree programs. Moreover, this could be set up via matching funds that incentivize state and local governments as well as philanthropic players to play a larger role in creating wraparound supports and administrative structures that would allow community colleges to better provide these services in the long term.

Recommendation 5. Federal, state, and local policymakers, working with large grant-writing foundations, should focus funding on interventions proven to result in higher graduation, transfer, and employment rates. As a first step, Congress should pass laws mandating the creation of datasets that merge educational and earnings data, which will help decision-makers and funders link dollars to outcomes.

Despite the success of programs such as ASAP and Project Quest, there is still a dearth of high-quality studies on comprehensive interventions. This is partly because there are relatively few such programs to begin with. Nonetheless, early results seem promising. The question is, how can we ensure that programs are properly measured in order to enable further public, private, and nonprofit financing?

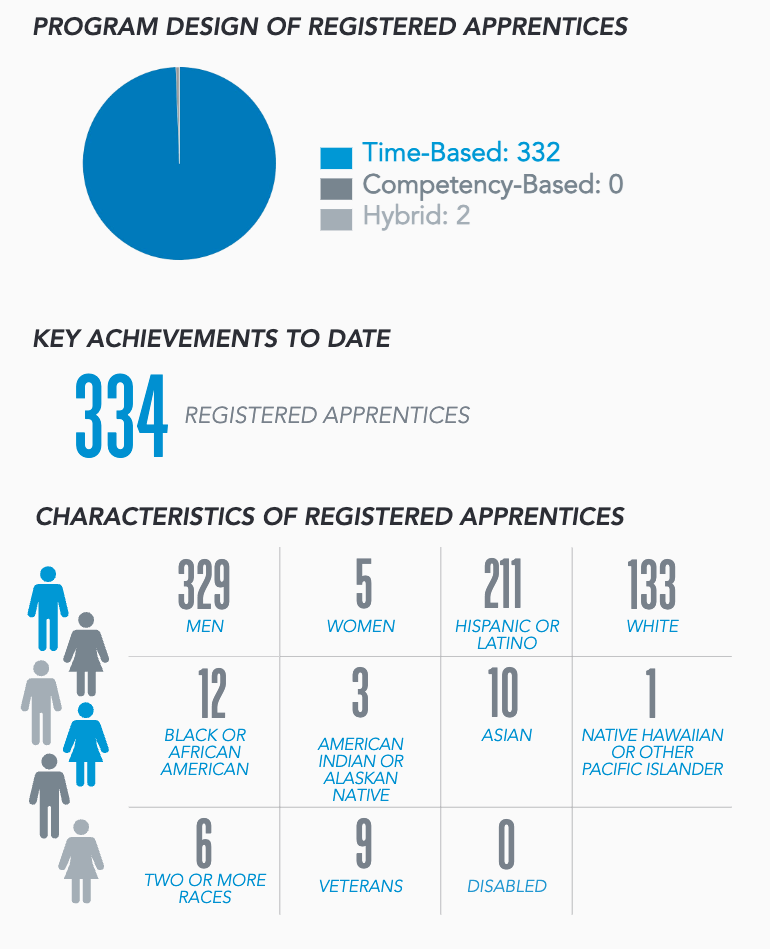

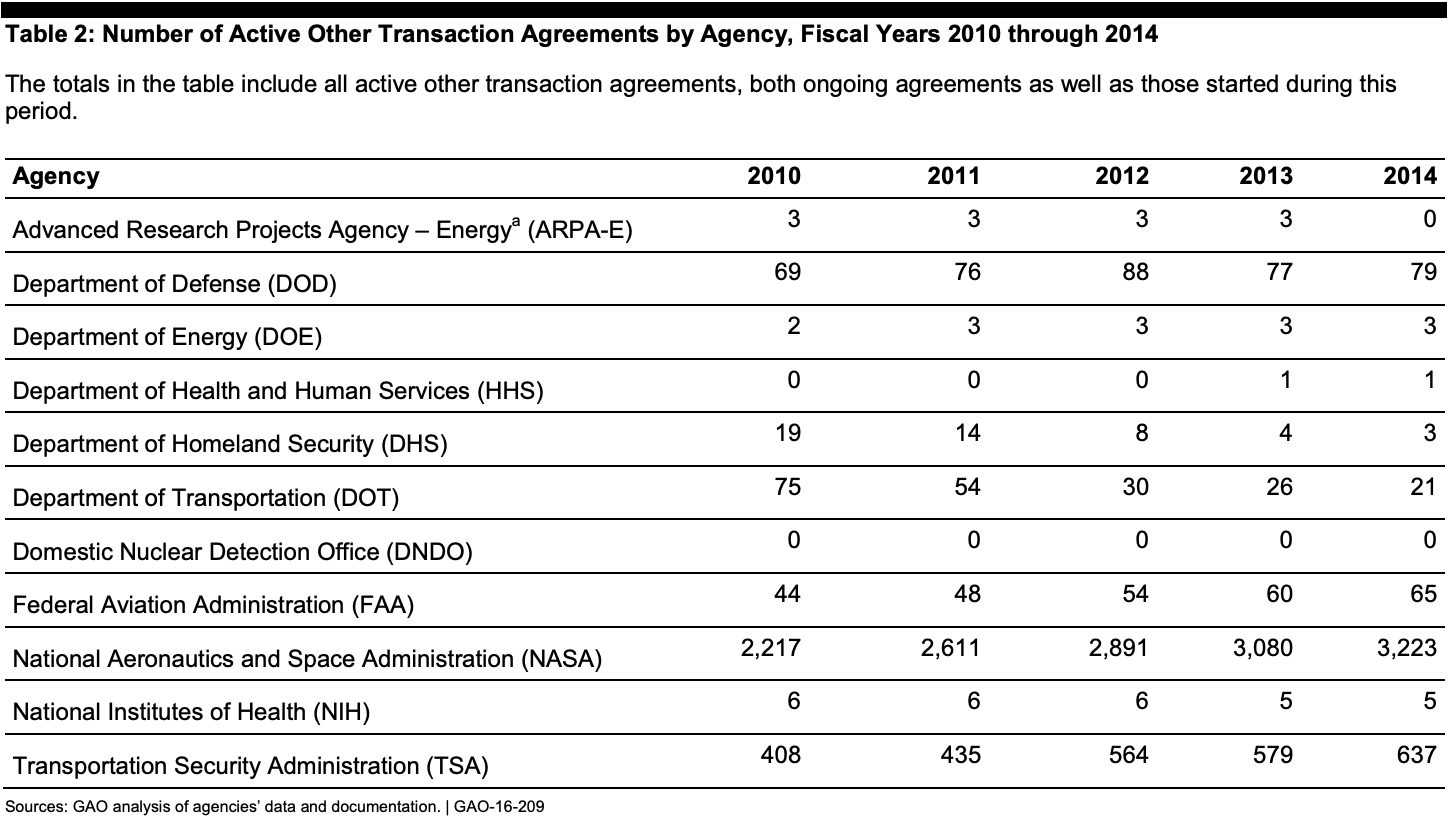

Unlike ASAP and Project Quest, most programs do not rigorously track data over a long period. For instance, the American Association of Community Colleges provides a repository of data on community college apprenticeships, broken out at an aggregate level as well as by school partner. However, a closer look shows that the public-facing dataset is missing rudimentary information on the number of apprentices who complete their programs, what types of programs have a high rate of completers versus non completers, and employment outcomes, let alone richer datasets that include background demographic information, longitudinal earnings tracking, and other pieces of information essential to constructing statistically rigorous studies of student ROI.

While there may be more privately held data in their database, the paucity of available public information is indicative of the state of data tracking for community colleges and work-based training programs. In general, institutions are not sufficiently funded to continue data tracking beyond completion or departure, leaving enormous gaps.

One way to get around this issue is to require more rigorous data collection and longitudinal tracking, leveraging existing administrative data where possible. Fortunately, there is already a bill on the floor, called the College Transparency Act, which includes provisions requiring the Education Department to match student-level data with IRS tax data to measure post completion employment rates as well as mean and median earnings by institution, program of study, and credential level. Congress should pass the act, which enjoys bipartisan support. Passing the College Transparency Act would create the much-needed foundation to rigorously compare ROI and enable greater accountability for community colleges and higher ed writ large.

Conclusion

Designed correctly, community colleges can be fonts of economic opportunity, especially for individuals from underserved backgrounds whose primary goal is to enter into a well-paying role upon program completion. By collecting high-quality data, focusing on degrees with strong outcomes, providing quality work-based training, and funding wraparound supports and tuition assistance, community colleges can be much stronger, more effective engines for students and local communities. While these reforms will take time and energy from public policymakers, community college leaders, and employers, they have the potential to deliver compelling outcomes and are worth the investment.

Certain constituents would be negatively impacted: for example, high school dual enrollment students would have fewer options for advanced course offerings, and students who want a physics, biology, economics, or similar degree would need to choose a four-year university. On the other hand, this is likely a healthy outcome. Academically gifted high school students could take AP courses in person at their high school or virtually, while liberal arts students would end up at four-year institutions where there is an appropriate amount of time to master the subject matter and the degree ROI is clearer.

The Ohio ASAP program included the following elements:

- Tutoring: Students were required to attend tutoring if they were taking developmental (remedial) courses, on academic probation, or identified as struggling by a faculty member or adviser.

- Career services: Students were required to meet with campus career services staff or participate in an approved career services event once per semester.

- Tuition waiver: A tuition waiver covered any gap between financial aid and college tuition and fees.

Monthly incentive: Students were offered a monthly incentive in the form of a $50 gas/grocery gift card, contingent on participation in program services. - Textbook voucher: A voucher covered textbook costs.

- Course enrollment: Blocked courses and consolidated schedules held seats for program students in specific sections of courses during the first year.

- First-year seminar: New students were required to take a first-year seminar (or “success course”) covering topics such as study skills and note-taking.

- Full-time enrollment: Students were required to attend college full-time during the fall and spring semesters and were encouraged to enroll in summer classes.

Although the program cost an additional $5,500 in direct costs per student (and a further $2,500 because students took more courses and degrees), the total cost per degree attained decreased because the program had a significant positive impact on graduation rates. Degree attainment is an essential key performance indicator because there are large differences in economic ROI for graduates and nongraduates, especially at community colleges.

Greater experimentation with publicly funded wraparounds, including greater uptake of entitlements for which students might be eligible, will help policymakers identify the most impactful components of the ASAP intervention. Over time, this will reduce direct costs while continuing to improve the cost per degree attained.

Project Quest included the following wraparound supports:

- Financial assistance to cover tuition and fees for classes, books, transportation, uniforms, licensing exams, and tutoring.

- Remedial instruction in math and reading to help individuals pass placement tests.

- Counseling to address personal and academic concerns and provide motivation and emotional support.

- Referrals to outside agencies for assistance with utility bills, childcare, food, and other services as well as direct financial assistance with other supports on an as-needed basis.

- Weekly meetings that focused on life skills, including time management, study skills, critical thinking, and conflict resolution.

- Job placement assistance, including help with writing résumés and interviewing, as well as referrals to employers that are hiring.

A study by Brookings and Opportunity America of graduates between 2010 and 2017 showed dramatic increases in five-year post completion wages (almost $100,000 for FAME graduates versus slightly over $50,000 for non-FAME participants). Much of the earnings impact can be attributed to differences in graduation rates: 80% of FAME participants graduate, compared to 30% elsewhere. It should be noted that FAME was not a randomized control trial (unlike Project Quest) but rather a match-paired study with a FAME participant and a “similar” individual, and data was only available for 24 of the 143 FAME participants at the five-year postgraduation mark. Nonetheless, research clearly shows that corporations, workforce development agencies, and community colleges can pair the best of Project Quest and FAME (the wraparound support provided by Quest, the broad and high-quality training in FAME, and the focus on high-demand roles in both) to optimize students’ outcomes.

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) youth apprenticeship and Perkins V programs have appropriated funding that could be used to expand work-based training for community college students. For 2022–2023, Congress appropriated $933 million for youth activities under WIOA, while Perkins V provides roughly $1.4 billion in state formula grants for youth and adult training. However, 75% of WIOA funding goes to out-of-school youth, while Perkins funding covers a wide range of career and technical education programs across secondary, postsecondary, and adult learning. Either program could administer additional funding focused on work-based learning tied to a community college degree, but Congress should appropriate or divert funds to serve these needs. Philanthropic funds could also play a role, especially in funding wraparound supports and administrative expenses, but centralized public funding is needed to ensure appropriate funding and rollout.

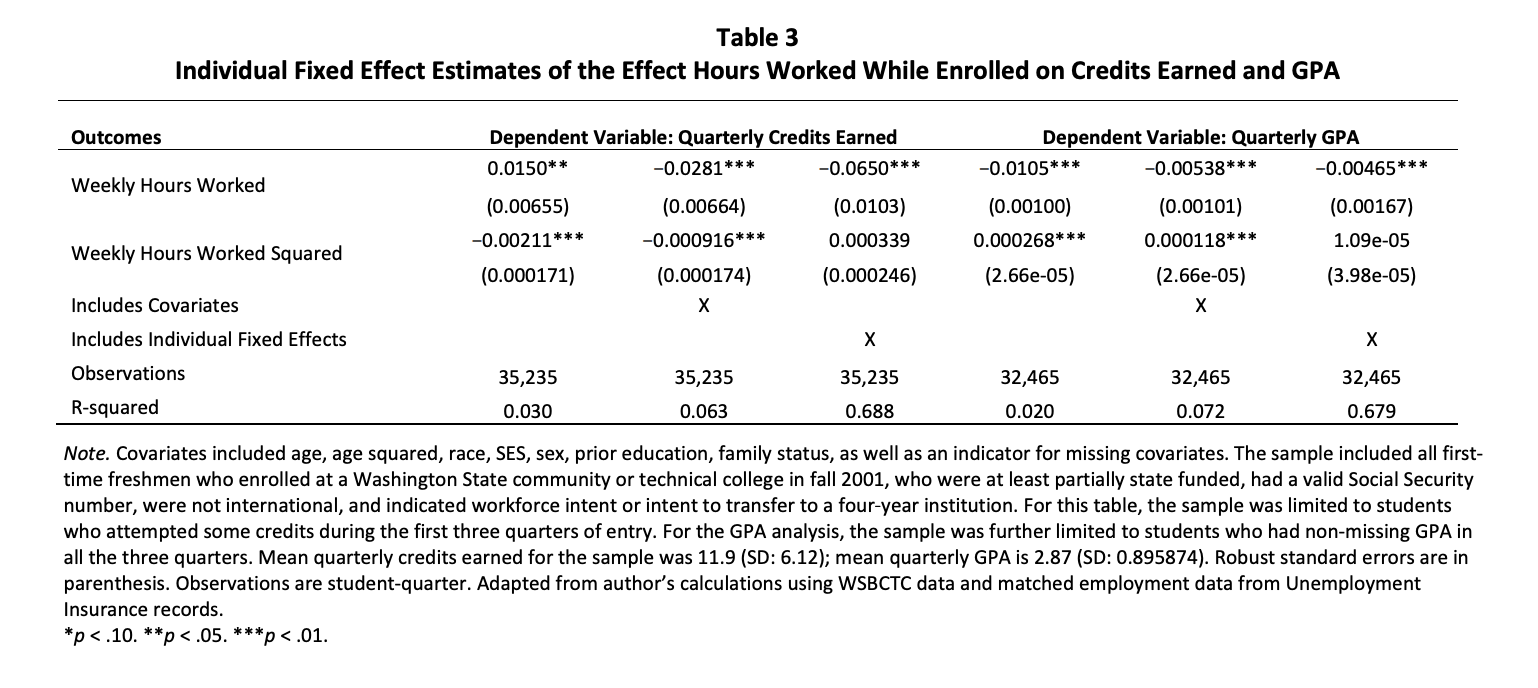

Contrary to popular belief, working while going to community college does not necessarily detract from student performance. Researcher Mina Dadgar pulled over 40,000 community college student records from the state of Washington and linked them to tax data. Although work did have a statistically significant negative impact on quarterly credits earned and GPA, it does not have a practically significant negative effect on student outcomes.

From the regression analysis above, we can see that each additional hour of work reduces the quarterly credits earned by .065 credits and grade point average (GPA) by roughly .005 points. Assuming that a student works 15 hours per week, the student would be expected to take one less credit per quarter, or three credits assuming that they are enrolled throughout the year. This is, in effect, one class per year, which while not negligible is not a major loss to academic attainment. Similarly, working 15 hours per week would predict a GPA decline of about .06 points—again, not a substantial effect on academic performance.

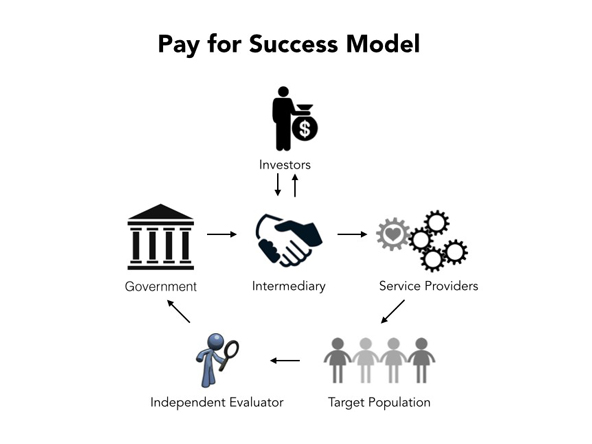

One promising structure is the social impact bond (sometimes referred to as pay for success). In this model, private investors provide upfront capital to social intervention programs and are repaid if certain performance targets are met. Although establishing the proper baseline can be challenging, the contract involves payment for reducing the overall cost of service (for instance, interventions that proactively reduce recidivism or hospital visits for chronic disease).

Existing programs focus on the financial returns of “investing” in students’ training and upskilling: for instance, impact financier Social Finance and coding bootcamp General Assembly launched a career impact bond that has funded over 800 underserved individuals seeking a credential in technology. However, there is the potential for much broader assessments of economic value that increase the appeal of comprehensive wraparound solutions. In the case of workforce training, the ideal program design might involve an assessment of the overall reduction in social services associated with individuals trapped in poverty (for instance, increased healthcare costs or extended social services provision) as well as the increase in economic activity and tax receipts from a higher-paying job.

As a result, these types of targets encourage more holistic interventions such as the ones we see in the ASAP and Project Quest programs because investors and program managers benefit from students’ long-term success, not just their short-term success. This also incentivizes rigorous data tracking, which in the long term will provide critical information on intervention packages that have the strongest positive impact while weeding out those that are not as effective in improving outcomes.

Developing a Mentor-Protégé Program for Fintech SBLC Lenders

Summary

The Biden Administration has recognized that small businesses, particularly minority-owned small businesses lack adequate access to capital. While SBA has operated its 7(a) Loan Program for multiple decades the program has historically shown poor results reaching minority-owned businesses and those in low- and moderate-income communities. Recently, the SBA has leveraged innovative fintech lenders to help fill this gap.

While the agency has finalized a rule that would allow fintech companies to participate in the 7(a) Loan Program, there are significant concerns that new entrants would put the program at risk due to a lack of internal controls and transparent evaluation. To help increase lending to low- and moderate-income communities while not increasing the overall risk to the 7(a) Loan Program, SBA should establish a mentor-protégé program and conditional certification regime for innovative financial technology companies to participate responsibly in the SBA’s 7(a) Loan Program and ensure that SBA adequately preserves the safety and soundness of the program.

The Challenge

The Biden Administration has recognized that small businesses, particularly minority-owned small businesses lack adequate access to capital. While SBA has operated its 7(a) Loan Program for multiple decades, the program has historically shown poor results in reaching minority-owned businesses and those in low- and moderate-income communities. According to a 2022 Congressional Research Service report, “[i]n FY2021, 30.1% of 7(a) loan approvals ($10.98 billion of $36.54 billion) were [made] to minority-owned businesses (20.8% Asian, 6.0% Hispanic, 2.6% African American, and 0.7% American Indian)”.

SBA has made a concerted effort previously to increase 7(a) small business lending to underserved communities by establishing the Community Advantage (CA) 7(a) loan initiative. Launched as a pilot program in 2011 and subsequently reauthorized, the CA loan initiative has been successful in encouraging mission-driven nonprofit lenders to underserved communities; however, the impact has been relatively small when compared to the traditional 7(a) loan program. In FY 2022, the CA Pilot Program approved just 722 loans totaling $114,804; whereas the general SBA 7(a) Loan Program approved 3,501 loans totaling $3,498,234,800–an order of magnitude of difference.

The COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented demand for assistance to the country’s small businesses, as they were forced to close their doors and saw their revenues dwindle. Congress responded to this demand by passing the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which established one of the largest government-backed lending programs ever, the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). During the PPP, fintech lenders, which for this policy memo includes technology-savvy banks and nonbank financial institutions that operate online and through mobile applications, proved uniquely adept at serving small businesses in traditionally underserved communities, even without specific guidance to do so from the SBA.

Many of the borrowers assisted by fintech lenders did not have pre-existing borrowing relationships with a financial institution and were therefore deprioritized by traditional financial institutions offering PPP loans, who favored lending to small businesses with existing relationships. Previously published research showed that not only did fintech lenders receive more applications from businesses from Black and Hispanic-owned businesses, but also extended a significant amount of lending to these businesses. Fintech lenders therefore expanded the impact of the PPP to underserved borrowers and successfully bolstered the efforts of mission-driven lenders, such as Community Development Financial Institutions and Minority Depository Institutions. For example, Unity National Bank of Houston, a Minority Depository Institution partnered with Cross River, a tech-focused bank that partners with fintech companies, to increase its lending from 500 loans to nearly 200,000 loans by leveraging Cross River’s lending technology. Similarly, Accion Opportunity Fund, a large Community Development Financial Institution, partnered with Lending Club, another tech-focused lender, to improve both entities’ lending operations to borrowers that were underserved during the first round of the PPP. However, Community Development Financial Institutions and Minority Depository Institutions often face challenges procuring and implementing the technology needed to help scale their nontraditional lending activities, which limits the efficacy of their mission-driven lending in an increasingly internet-based lending environment.

In an effort to increase access to capital and build on the efforts of fintech companies that successfully provided capital to small businesses in the Paycheck Protection Program, SBA has proposed lifting its moratorium on non-depository lenders participating in the program. SBA and the Biden Administration have shown real progress in removing the moratorium on Small Business Lending Company (SBLC) licenses to include fintech companies, which would expand the eligible participants in the program for the first time in 40 years.

Expanding access to capital and support for small businesses is a key priority for the Biden Administration. Specifically, the Administration noted the importance of expanding underserved small business’ access to capital. They recommended expanding the SBA’s 7(a) program by extending SBLC licenses to nonbank lenders, which include fintech companies, as one promising strategy. To this end, SBA has established a strategy of expanding its lending network by leveraging fintech companies. The SBA previously issued a proposed rulemaking to remove the moratorium on SBLC licenses and add three new categories of SBLC licenses.

However, policymakers and some industry participants have cast serious doubts on fintech companies’ participation in SBA’s 7(a) Loan Program, due to weak internal controls of unpartnered fintech companies and subsequent fraud issues experienced during the Paycheck Protection Program. Further, these critics have cited concerns with the agency’s ability to properly oversee these fintech companies due to a lack of ability to manage the fraud risks associated with developing or expanding a lending program that includes unpartnered fintech companies. Overall, the agency has shown that both it and fintech companies should improve their engagement together to ensure that the many program requirements are adhered to, and that SBA improves its abilities to mitigate potentially new or unique risks to the 7(a) Loan Program.

The Plan of Action

To solve the aforementioned issues, SBA should establish a mentor-protégé program and conditional certification regime for innovative nonbank financial technology companies to participate responsibly in the SBA’s 7(a) Loan Program. By creating a mentor-protégé program and conditional certification regime, SBA can continue to encourage the expansion of the 7(a) Loan Program to lenders that have shown their willingness and ability to lend to traditionally underserved small business borrowers, while ensuring that the agency adequately preserves the safety and soundness of the 7(a) Loan Program.

In the proposed mentor-protégé program, SBA would conduct an initial assessment of the fintech applicant and provide a conditional certification contingent on the fintech’s participation in the mentor-protégé program. To ensure that only the most well-suited fintech companies are allowed to engage in the 7(a) program, SBA should conduct a fair lending assessment. This would include a gap analysis of the company’s lending processes, akin to the existing interagency fair lending examinations conducted by the federal banking regulators. Further, SBA should require fintech companies to complete a “Community Lending Plan” detailing the specific small business lending activities the fintech company intends to complete in traditionally underserved areas. SBA would conduct a review of applications it receives and match them with banks that are established 7(a) lenders.

To help ensure that both mentors and protégés develop throughout the program, SBA would need to create program criteria for both mentor banks and protégé fintech companies. Mentor criteria should focus on ensuring that mentor banks assist and grow the knowledge of their fintech proteges. Thus, both mentors and protégés should be required to complete periodic progress reports. Further, mentors should conduct their own periodic assessments of the fintech protégé’s compliance and lending processes to ensure that the fintech is able to comply with existing 7(a) Loan Program requirements and not create an undue risk to the program. These criteria should be determined based on the expertise of the Office of Capital Access and Office of Credit Risk Management with advice from SBA’s 8(a) Business Development Program staff. Lastly, to ensure that mentors and protégés can speak candidly about their experience with the other participant, SBA would need to create communication portals for both entities that are walled-off review by either participant.

Recognizing the potential apprehension existing 7(a) lenders might have to eventually increasing competition to the 7(a) lending market, the SBA would need to incentivize banks to provide mentorship services to fintech companies by providing participating mentor banks with Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) credit and an increased SBA guarantee threshold for the bank’s 7(a) loans. By pursuing these two incentives, the SBA would provide banks with clear business and regulatory benefits from participating in the mentor-protégé program.

Based on a review of the SBA’s 2023 Congressional Budget Justification, SBA has accounted for much of the increased cost that would stem from expanding the 7(a) Lending Program to additional SBLCs. SBA noted that part of its $93.6 million request for fiscal year 2023 was to attract new lenders that participated in the Paycheck Protection Program. Similarly, SBA identified the need to continue building its oversight of Paycheck Protection Program and Community Advantage lenders. To this end, SBA requested an additional $13.9 million in small business lender oversight. Establishing the 7(a) mentor-protégé program would likely require only a small amount of additional funds relative to the 2023 requested amount. To account for the additional programmatic and administrative requirements needed to establish the 7(a) mentor-protégé program, SBA should include an additional $500 thousand to $1 million to its future Congressional Budget Justifications.

Success of the mentor-protégé program depends on robust program requirements and continuous monitoring to ensure the participants are adhering to the goal of responsibly expanding capital access to underserved small businesses. To accomplish this endeavor, SBA should leverage the internal expertise of its Office of Capital Access and Office of Credit Risk Management, while also coordinating with prudential and state financial services regulators to adequately understand the novel business models of fintech companies applying to and participating in the program. Interagency coordination between state and federal regulators will ensure that the 7(a) program’s integrity is maintained at the macro and micro levels.

Conclusion

Expanding small business lending to low- and moderate- income communities is an especially important endeavor. Few opportunities for real social and economic growth exist in these traditionally underserved communities without robust access to small business credit. While the importance of expanding access is clear, SBA has a responsibility to ensure that its flagship 7(a) Loan Program remains safe, sound, and available for the benefit of all small businesses. The recent decision to finalize rulemaking that would expand allowable lenders to the 7(a) Loan Program must come with careful consideration of which lenders should be able to participate. Incorporating fintech lenders presents an opportunity to solve the issues of small business lending to traditionally underserved communities. However, given the concerns identified throughout the rulemaking process and after its finalization, SBA should work diligently to ensure that only the best-suited entities are allowed to become 7(a) lenders. To help ensure that this occurs, they should create a mentor-protégé program that will afford fintech companies the best opportunity to succeed in the program while maintaining the safety and soundness that is so important to the overall success of the 7(a) Loan Program.

Expanding access to capital and support for small businesses is a key priority for the Biden Administration. Specifically, the Administration noted the importance of expanding underserved small business’ access to capital by expanding the SBA’s 7(a) program through extending SBLC licenses to nonbank lenders, which include fintech companies. To this end, SBA established a strategy of expanding its lending network by leveraging fintech companies. The SBA previously issued and finalized a rulemaking process to remove the moratorium on SBLC licenses and add three new categories of SBLC licenses.

Success of the mentor-protégé program depends on robust program requirements and continuous monitoring to ensure the participants are adhering to the goal of responsibly expanding capital access to underserved small businesses. To accomplish this endeavor, SBA should leverage the internal expertise of its Office of Capital Access and Office of Credit Risk Management, while also coordinating with prudential and state financial services regulators to adequately understand the novel business models of fintech companies applying to and participating in the program.

The SBA can conduct an initial assessment of the fintech applicant and provide a conditional certification contingent on the fintech’s participation in the mentor-protégé program. Further, the SBA should develop program criteria for both mentor banks and protégé fintech companies and application portals for both entities. SBA would conduct a review of applications it receives. The SBA would incentivize banks to provide mentorship services to fintech companies seeking to gain SBLC certification by providing CRA credit banks and an increased SBA guarantee threshold for the bank’s 7(a) loans.

Providing equitable access to capital for underserved communities in our country will require actions beyond the scope of this policy recommendation, including changes to the regulations that govern community banks, fintech lenders, CDFIs, and other mission-driven lenders. Fintech lenders have a proven ability to contribute to this expansion of capital access, given their collective performance as PPP lenders. In addition, fintech lenders have an ability to scale the solutions that they provide quickly, something that CDFIs and other mission-led lenders have traditionally struggled to do well.

Fintech lenders compete with conventional lenders for market share; the SBA should take care not to create programs that give one competing group an advantage over another. Creating a bespoke program, tailored to the needs of fintech lenders, would run the risk of creating more than an incidental competitive advantage. Instead, this program proposal advocates for utilizing a mentorship model that helps build strategic partnerships to accelerate access to capital for underserved groups, without creating separate rules or carve-outs.

Aligning U.S. Workforce Investment for Energy Security and Supply Chain Resilience

With the passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the United States has outlined a de facto industrial policy to facilitate and accelerate the energy transition while seeking energy security and supply chain resilience. The rapid pace of industrial transformation driven by the energy transition will manifest as a human capital challenge, and the workforce will be realigned to the industrial policy that is rapidly transforming the labor market. The energy transition, combined with nearshoring, will rapidly retool the global economy and, with it, the skills and expertise necessary for workers to succeed in the labor market. A rapid, massive, and ongoing overhaul of workforce development systems will allow today’s and tomorrow’s workers to power the transition to energy security, resilient supply chains, and the new energy economy—but they require the right training opportunities scaled to match the needs of industry to do so.

Policymakers and legislators recognize this challenge, yet strategies and programs often sit in disparate parts of government agencies in labor, trade, commerce, and education. A single strategy that coordinates a diverse range of government policies and programs dedicated to training this emerging workforce can transform how young people prepare for and access the labor market and equip them with the tools to have a chance at economic security and well-being.

Modeled after the U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) program, we propose the Energy Security Workforce Training (ESWT) Initiative to align existing U.S. government support for education and training focused on the jobs powering the energy transition. The Biden-Harris Administration should name an ESWT Coordinator to manage and align domestic investments in training and workforce across the federal government. The coordinator will spearhead efforts to identify skills gaps with industry, host a ESWT White House Summit to galvanize private and social sector commitments, encourage data normalization and sharing between training programs to identify what works, and ensure funds from existing programs scale evidence-based sector-specific training programs. ESWT should also encompass an international component for nearshored supply chains to perform a similar function to the domestic coordinator in target countries like Mexico and promote two-way learning between domestic and international agencies on successful workforce training investments in clean energy and advanced manufacturing.

Challenge and Opportunity

With the passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, the United States has a de facto industrial policy to facilitate and accelerate the energy transition while seeking energy security and supply chain resilience. However, our current workforce investments are not focused on the growing green skills gap. We require workforce investment aligned to the industrial policy that is rapidly transforming the labor market, to support both domestic jobs and the foreign supply chains that domestic jobs depend on.

Preparing Americans to Power the Energy Transition

The rapid pace of industrial transformation driven by the energy transition will manifest as a human capital challenge. The energy transition will transform and create new jobs—requiring a massive investment to skill up the workers who will power the energy transition. Driving this rapid transition are billions of dollars slated for incentives and tax credits for renewable energy and infrastructure, advanced manufacturing, and supply chain creation for goods like electric vehicle batteries over the coming years. The vast upheaval caused by the energy transition combined with nearshoring is transforming both current jobs as well as the labor market young people will enter over the coming decade. The jobs created by the energy transition have the potential to shift a whole generation into the middle class while providing meaningful, engaging work.

Moving low-income students into the middle class over the next 10 years will require that education and training institutions meet the rapid pace of industrial transformation required by the energy transition. Education and training providers struggle to keep up with the rapid pace of industrial transformation, resulting in skills gaps. Skills gaps are the distance between the skills graduates leave education and training with and the skills required by industry. Skills gaps rob young people of opportunities and firms of productivity. And according to LinkedIn’s latest Green Economy report, we are facing a green skills gap—with the demand for green skills outpacing the supply in the labor force. Firms have cited skills gaps in diverse sectors related to the energy transition, including infrastructure, direct air capture, electromobility, and geothermal power.

Graduates with market-relevant skills earn between two and six times what their peers earn, based on evaluations of International Youth Foundation’s (IYF) programming. In addition, effective workforce development lowers recruitment, selection, and training costs for firms—thereby lowering the transaction costs to scale moving people into the positions needed to power the energy transition. Industrial transformation for the energy transition involves automation, remote sensing, and networked processes changing the role of the technician—who is no longer required to execute tasks but instead to manage automated processes and robots that now execute tasks. This changes the fundamental skills required of technicians to include higher-order skills for managing processes and robots.

We will not be able to transform industry or seize the opportunities of the new energy future without overhauling education and training systems to build the skills required by this transformation and the industries that will power it. Developing higher-order thinking skills means changing not only what is taught but how teaching happens. For example, students may be asked to evaluate and make actionable recommendations to improve energy efficiency at their school. Because many of these new jobs require higher-order thinking skills, policy investment can play a crucial role in supporting workers and those entering the workforce to be competitive for these jobs.

Creating Resilient Supply Chains, Facilitating Energy Security, and Promoting Global Stability in Strategic Markets

Moving young people into good jobs during this dramatic economic transformation will be critical not only in the United States but also to promote our interests abroad by (1) creating resilient supply chains, 2) securing critical minerals, and (3) avoiding extreme labor market disruptions in the face of a global youth bulge.

Supply chain resilience concerns are nearshoring industrial production—shifting the demand for industrial workers across geographies at a shocking scale and speed—as more manufacturing and heavy industries move back into the United States’ sphere of influence. The energy transition combined with nearshoring will rapidly retool the global economy. We need a rapid, massive, and ongoing overhaul of workforce development systems at home and abroad. The scale of this transition is massive and includes complex, multinational supply chains. Supply chains are being reworked before our eyes as we nearshore production. For example, the port of entry in Santa Teresa, New Mexico, is undergoing rapid expansion in anticipation of explosive growth of imports of spare parts for electric vehicles manufactured in Mexico. These shifting supply chains will require the strategic development of a new workforce.

The United States requires compelling models to increase its soft power to secure critical minerals for the energy transition. Securing crucial minerals for the energy transition will again reshape energy supply chains, as the mineral deposits needed for the energy transition are not necessarily located in the same countries with large oil, gas, or coal deposits. The minerals required for the energy transition are concentrated in China, Democratic Republic of Congo, Australia, Chile, Russia, and South Africa. We require additional levers to establish productive relationships to secure the minerals required for the energy transition. Workforce investments can be an important source of soft power.

Today’s 1.2 billion young people today make up the largest and most educated generation the world has ever seen, or will ever see, yet they face unemployment rates at nearly triple that of adults. Globally the youth unemployment rate is 17.93% vs. 6.18% for adults. The youth unemployment rate refers to young people aged 15–24 who are available for or seeking employment but who are unemployed. While rich countries have already passed through their own baby booms, with accompanying “youth bulges,” and collected their demographic dividends to power economic growth and wealth, much of the developing world is going through its own demographic transition. While South Korea experienced sustained prosperity once its baby boomers entered the labor force in the early 2000s, Latin America’s youth bulge is just entering the labor force. In regions like Central America, this demographic change is fueling a wave of outmigration. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the youth bulge is making its way through compulsory education with increasing demands for government policy to meet high rates of youth unemployment. It is an open question whether today’s youth bulges globally will drive prosperity as they enter the labor market. Policymakers are faced with shaping labor force training, and government policy rooted in demonstrable industry needs to meet this challenge. At the same time, green jobs is already one of the most rapidly growing occupations. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that adopting clean energy technologies will generate 14 million jobs by 2030, with 16 million more to retrofit and construct energy-efficient buildings and manufacture new energy vehicles. At the same time, the World Economic Forum’s 2023 future of jobs report cites the green transition as the key driver of job growth. However, the developing world is not making the corresponding investments in training programs for the green jobs that are driving growth.

Alignment with Existing Initiatives

The Biden-Harris Administration’s approach to the energy transition, supply chain resilience, and energy security must address this human capital challenge. Systemic approaches to building the skills for the energy transition through education and training complement the IRA’s incentivized apprenticeships, and focus investments from the IIJA, by building out a complete technical, vocational, education and training system oriented toward building the skills required for the energy transition. We propose a whole-of-government approach that integrates public investment in workforce training to focus on the energy transition and nearshoring with effective approaches to workforce development to address the growing green skills gap that endangers youth employment, the energy transition, energy security and supply chain resilience.

The Biden-Harris Administration Roadmap to Support Good Jobs demonstrates a commitment to building employment and job training into the Investing in America Agenda. The Roadmap catalogs programs throughout the federal government that address employment and workforce training authorized in recent legislation and meant to enable more opportunities for workers to engage with new technology, advanced manufacturing, and clean energy. Some programs had cross-sector reach, like the Good Jobs Challenge that reached 32 states and territories authorized in the American Rescue Plan to invest in workforce partnerships, while others are more targeted to specific industries, like the Battery Workforce Initiative that engages industry in developing a battery manufacturing workforce. The Roadmap’s clearinghouse of related workforce activities across the federal ecosystem presents a meaningful opportunity to advance this commitment by coordinating and strategically implementing these programs under a single series of objectives and metrics.

Identifying evidence-driven training programs can also help fill the gap between practicums and market-based job needs by allowing more students access to practical training than can be reached solely by apprenticeships, which can have high individual transaction costs for grantees to coordinate. Additionally, programs like the Good Jobs Challenge required grantees to complete a skills-gap analysis to ensure their programs fit market needs. The Administration should seek to embed capabilities to conduct skills-gap analyses first before competitive grants are requested and issued to better inform program and grant design from the beginning and to share that learning with the broader workforce training community. By using a coordinated initiative to engage across these programs and legislative mandates, the Administration can create a more catalytic, scalable whole-of-government approach to workforce training.

Collaborating on metrics can also help identify which programs are most effective at meeting the core metrics of workforce training—increased income and job placements—which often are not met in workforce programs. This initiative could be measured across programs and agencies by (1) the successful hiring of workers into quality green jobs, (2) the reduction of employer recruitment and training costs for green jobs, and (3) demonstrable decreases in identified skills gaps—as opposed to a diversity of measures without clear comparability that correspond to the myriad agencies and congressional committees that oversee current workforce investments. Better transferable data measured against comparable metrics can empower agencies and Congress to direct continued funds toward what works to ensure workforce programs are effective.

The DOL’s TAACCCT program provides a model of how the United States has successfully invested in workforce development to respond to labor market shocks in the past. Building on TAACCCT’s legacy and its lessons learned, we propose focusing investment in workforce training to address identified skills gaps in partnership with industry, engaging employers from day one, rather than primarily targeting investment based on participant eligibility. When investing in bridging critical skills gaps in the labor market, strategy and programs must be designed to work with the most marginalized communities (including rural, tribal, and Justice40 communities) to ensure equitable access and participation.

Increased interagency collaboration is required to meet the labor market demands of the energy transition, both in terms of domestic production in the United States and the greening of international supply chains from Mexico to South Africa. Our proposed youth workforce global strategy, the Energy Security Workforce Training Initiative outlined below provides a timely opportunity for the Administration to make progress on its economic development, workforce and climate goals.

Plan of Action

We propose a new Energy Security Workforce Training Initiative to coordinate youth workforce development training investments across the federal government, focused on critical and nearshored supply chains that will power energy security. ESWT will be charged with coordinating U.S. government workforce strategies to build the pipeline for young people to the jobs powering the energy transition. ESWT will rework existing education and training institutions to build critical skills and to transform how young people are oriented to, prepared for, and connected to jobs powering the energy transition. ESWT will play a critical role in cross-sector and intergovernmental learning to invest in what works and to ensure federal workforce investments in collaboration with industry address identified skills gaps in the labor market for the energy transition and resilient supply chains. Research and industry confirmation would inform investments by the Department of Energy (DOE), Department of Education (ED), Department of Commerce (DOC), and Department of Labor (DOL) toward building identified critical skills through scalable means with marginalized communities in mind. A key facet of ESWT will be to normalize and align the metrics by which federal, state, and local partners measure program effectiveness to allow for better comparability and long-term potential for scaling the most evidence-driven programs.

The ESWT should be coordinated by the National Economic Council(NEC) and DOC, particularly the Economic Development Administration. Once established, ESWT should also involve an international component focused on workforce investments to build resilience in nearshore supply chains on which U.S. manufacturing and energy security rely. Mexico should serve as an initial pilot of this global initiative because of its intertwined relationship with U.S. supply chains for products like EV batteries. Piloting a novel international workforce training program through private sector collaboration and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), DOL, and U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) investments could help bolster resilience for domestic jobs and manufacturing. Based on these results, ESWT could expand into other geographies of critical supply chains, such as Chile and Brazil. To launch ESWT, the Biden Administration should pursue the following steps.

Recommendation 1. The NEC should name an ESWT Initiative Coordinator in conjunction with a DOC or DOL lead who will spearhead coordination between different agency workforce training activities.

With limited growth in government funding over the coming years, a key challenge will be more effectively coordinating existing programs and funds in service of training young people for demonstrated skills gaps in the marketplace. As these new programs are implemented through existing legislation, a central entity in charge of coordinating implementation, learning, and investments can best ensure that funds are directed equitably and effectively. Additionally, this initial declaration can lay the groundwork to build capacity within the federal government to conduct market analyses and consult with industries to better inform program design and grant giving across the country. The DOC and the Economic Development Administration seem best positioned to lead this effort with an existing track record through the Good Jobs Challenge and capacity to engage fully with industry to build trust that curricula and training are conducted by people that employers verify as experts. However, the DOL could also take a co-lead role due to authorities established under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). In selecting lead agencies for ESWT, these criteria should be followed:

- Access to emerging business intelligence regarding industry-critical skills—DOC, DOE

- Combined international and domestic remit—DOE/DOL, DOC (ITA)

- Remit that allows department to focus investment on demonstrated skills gaps, indicated by higher wages and churn—DOC

- Permitted to convene advisory committees from the private sector under the Federal Advisory Committee Act—DOC

Recommendation 2. The DOC and NEC, working with partner agencies, should collaborate to identify and analyze skills gaps and establish private-sector feedback councils to consult on real-time industry needs.

As a first step, DOC should commission or conduct research to identify quantitative and qualitative skills gaps related to the energy transition in critical supply chains both domestically and in key international markets — energy efficiency in advanced manufacturing, electric vehicle production, steel, batteries, rare earth minerals, construction, infrastructure and clean energy. DOC should budget for 20 skills gap assessments for critical occupational groups (high volume of jobs and uncertainty related to required, relevant skills) in the above-mentioned sectors. Each skills gap assessment should cost roughly $100,000, bringing the total investment to $2 million over a six-to-twelve-month period. Each skills gap assessment will determine the critical and scarce skills in a labor market for a given occupation and the degree to which existing education and training providers meet the demand for skills.

This research is central to forming effective programs to ensure investments align with industry skills needs and to lower direct costs on education providers, who often lack direct expertise in this form of analysis. Commissioning these studies can help build a robust ecosystem of labor market skills gap analysts and build capacity within the federal government to conduct these studies. By completing analysis in advance of competitive grant processes, federal grants can be better directed to training based on high-need industry skill sets to ensure participating students have market-driven employment opportunities on completion. The initial research phase would occur over a six-month timeline, including staffing and procurement. The ESWT coordinator would work with DOC, ED, and DOL to procure curricula, enrollment, and foreign labor market data. Partner agencies in this effort should also include the Departments of Education, Labor, and Energy. The research would draw upon existing research on the topic conducted by Jobs for the Future, IYF, the Project on Workforce at Harvard, and LinkedIn’s Economic Graph.

Recommendation 3. Host the Energy Security Workforce Development White House Summit to galvanize public, private, and social sector partners to address identified skills gaps.

The ESWT coordinator would present the identified quantitative and qualitative skills gaps at an action-oriented White House Summit with industry, state and local government partners, education providers, and philanthropic institutions. The Summit could serve as a youth-led gathering focused on workforce and upskilling for critical new industries and galvanize a call to action across sectors and localities. Participants will be asked to prioritize among potential choices based on research findings, available funding mechanisms, and imperatives to transform education and training systems at scale and at pace with industrial transformation. Addressing the identified skills gaps will require partnering with and securing the buy-in of both educational institutions as well as industry groups to identify what skills unlock opportunities in given labor markets, develop demand-driven training, and expanded capacity of education and training providers in order to align interests as well as curricula so that key players have the incentives and capacity to continually update curricula—creating lasting change at scale. This summit would also serve as a call to action for private sector partnerships to invest in helping reskill workers and establish buy-in from the public and civil society actors.

Recommendation 4. Establish standards and data sharing processes for linking existing training funds and programs with industry needs by convening state and local grantees, state agencies, and federal government partners.

ESWT should lay out a common series of metrics by which the federal government will assess workforce training programs to better equip efforts to scale successful programs with comparable evidence and empower policymakers to invest in what works. We recommend using the following metrics:

- Successful hiring of workers into quality green jobs

- The reduction of employer recruitment and training costs for green jobs

- Demonstrable decreases in identified skills gaps

Metrics 2 and 3 will rely on ongoing industry consultations—as well as data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Because of the diffuse nature of existing skills gap analyses across federal grantees and workforce training programs, ESWT should serve as a convenor for learning between jurisdictions. Models for federal government data clearinghouses could be effective as well as direct sharing of evidence and results between education providers across a series of common metrics.

Recommendation 5. Ensure grants and investments in workforce training are tied to addressing specific identified skills gaps, not just by regional employment rates.

A key function of ESWT would be to determine feasible and impactful strategies to address skills gaps in critical supply chains, given the identified gaps, existing funding mechanisms, the buy-in of critical actors in key labor markets (both domestic and international), agency priorities, and the imperative to make transformative change at scale. The coordinator could help spur agencies to pursue flexible procurement and grant-making focused on outcomes and tied to clear skills gap criteria to ensure training demonstrably develops skills required by market needs for the energy transition and growing domestic supply chains. While the Good Jobs Challenge required skills gap analysis of grantees, advanced analyses by the ESWT Initiative could inform grant requirements to ensure federal funds are directed to high-need programs. As many of these fields are new, innovative funding mechanisms could be used to meet identified skills gaps and experiment with new training programs through tiered evidence models. Establishing criteria for successful workforce training programs could also serve as a market demand-pull signal that the federal government is willing and able to invest in certain types of training, crowding-in potential new players and private sector resources to create programs tailored for the skills industry needs.

Depending on the local context, the key players, and the nature of the strategy to bridge the skills gap for each supply chain, the coordinating department will determine what financing mechanism and issuing agency is most appropriate: compacts, grants, cooperative agreements, or contracts. For example, to develop skills related to worker safety in rare-earth mineral mines in South Africa or South America, the DOL could issue a grant under the Bureau of International Labor Affairs. To develop the data science skills critical for industrial and residential energy efficiency, the ED could issue a grants program to replicate Los Angeles Unified School District’s Common Core-aligned data science curriculum.

Recommendation 6. Congress should authorize flexible workforce training grants to disperse—based on identified industry needs—toward evidence-driven, scalable training models and funding for ESWT within the DOC to facilitate continued industry skills need assessments.