How the NEED Act Would Ensure CHIPS Doesn’t Crumble

A year and a half after its passage, money is starting to flow from the CHIPS and Science Act to create high-paying, high-tech jobs. In Phoenix, for example, the chip manufacturer Intel will receive billions to help build two new computer chip manufacturing plants that will transform the area into one of the world’s most important players in modern electronics.

That project was one of several – totaling nearly $20 billion – announced recently with Intel for computer chip plants in Arizona, Ohio, New Mexico and Oregon. The company said the investments will create a combined 30,000 manufacturing and construction jobs.

With numbers like that, it’s easy to see why all of the attention and headlines for the legislation thus far have focused on the “CHIPS” part of the law. But now, it is time for Congress to put its bipartisan support behind the “and Science” or risk the momentum the law has created.

That’s because both the law and the semiconductor industry recognize that the U.S. needs a bigger, more inclusive science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) workforce to fulfill the needs of a robust high-tech manufacturing industry. While CHIPS sets the conditions for a revitalized domestic semiconductor industry, it also calls for improved “access to education, opportunity, and services” to support and develop the workers needed to fill these new jobs.

The numbers show the U.S. lags behind its global competitors when it comes to math and science achievement. Middle school math scores are exceptionally low: only 26 percent of all eighth-grade students scored “proficient” on the math portion of the National Assessment of Education Progress in 2022. This presents big problems down the road for higher education.

To put it more bluntly: at a time when CHIPS is poised to ramp up demand for STEM graduates, the nation’s education system is unprepared to produce them.

So what’s a fix? A good first step would be for Congress to pass the New Essential Education Discoveries (NEED) Act to improve the nation’s capabilities to conduct education research and development. NEED would create the National Center for Advanced Development in Education (NCADE), a new Center within the research arm of the U.S. Department of Education to develop innovative practices, tools, systems, and approaches to boost achievement among young people in the wake of the pandemic.

NCADE would enable an informed-risk, high-reward R&D strategy for education – the kind that’s already taking place in other sectors, like health, agriculture, and energy. It’s akin to the approach that fuels the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which has led to innovations like GPS, the Internet, stealth technology, and even the computer mouse. Education needs something like this, and NEED will create it – a flexible, nimble research center pushing transformational education innovations.

The passing of the CHIPS and Science Act was a strong indication that Republicans and Democrats can work together to solve big, complex problems when motivated to do so. Passing the NEED Act will show that the same bipartisan spirit can ensure the long-term success of the law while simultaneously setting the course for vast and fundamental improvements to the nation’s schools and universities through improved R&D in education.

CHIPS and Science Funding Gaps Continues to Stifle Scientific Competitiveness

The bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act sought to accelerate U.S. science and innovation, to let us compete globally and solve problems at home. The multifold CHIPS approach to science and tech reached well beyond semiconductors: it authorized long-term boosts for basic science and education, expanded the geography of place-based innovation, mandated a whole-of-government science strategy, and other moves.

But appropriations in FY 2024, and the strictures of the Fiscal Responsibility Act in FY 2025, make clear that we’re falling well short of CHIPS aspirations. The ongoing failure of the U.S. to invest comes at a time when our competitors continue to up their investments in science, with China pledging 10% growth in investment, the EU setting forth new strategies for biotechnology and manufacturing, and Korea’s economy approaching 5% R&D investment intensity, far more than the U.S.

Research Agency Funding Shortfalls

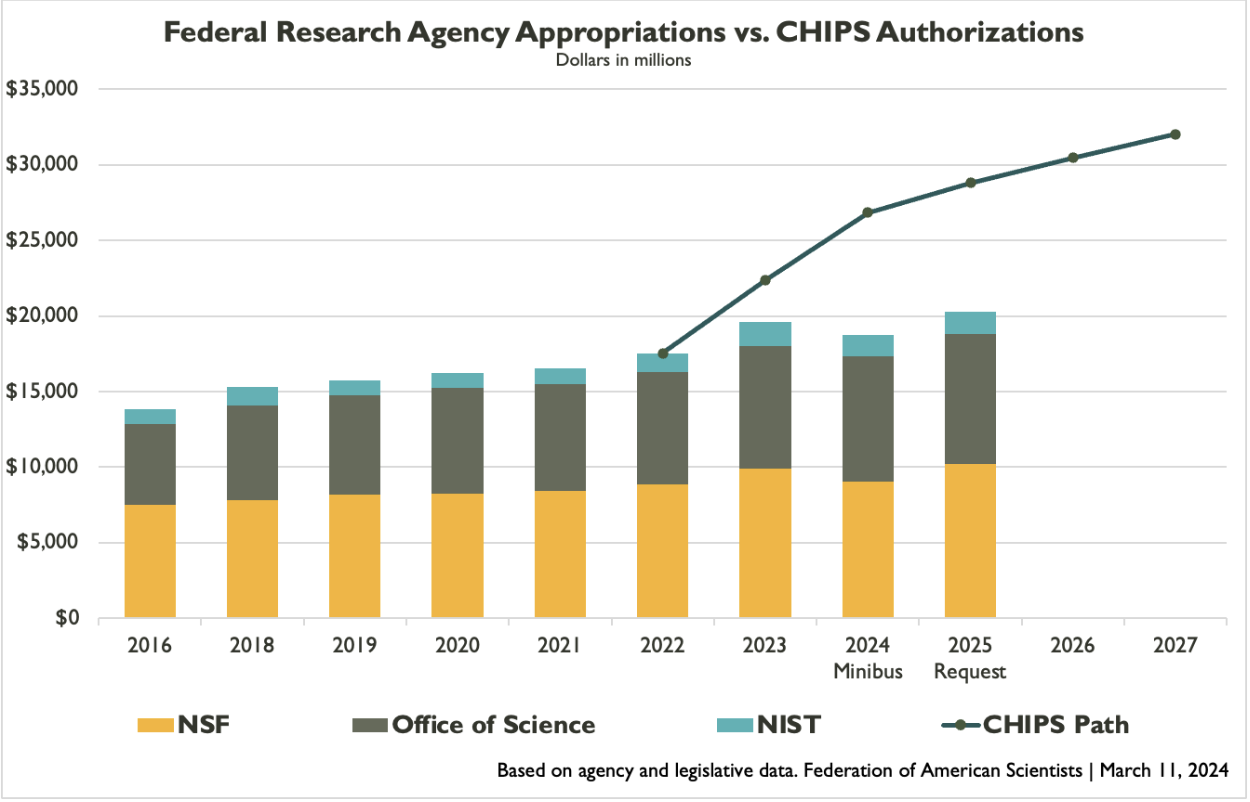

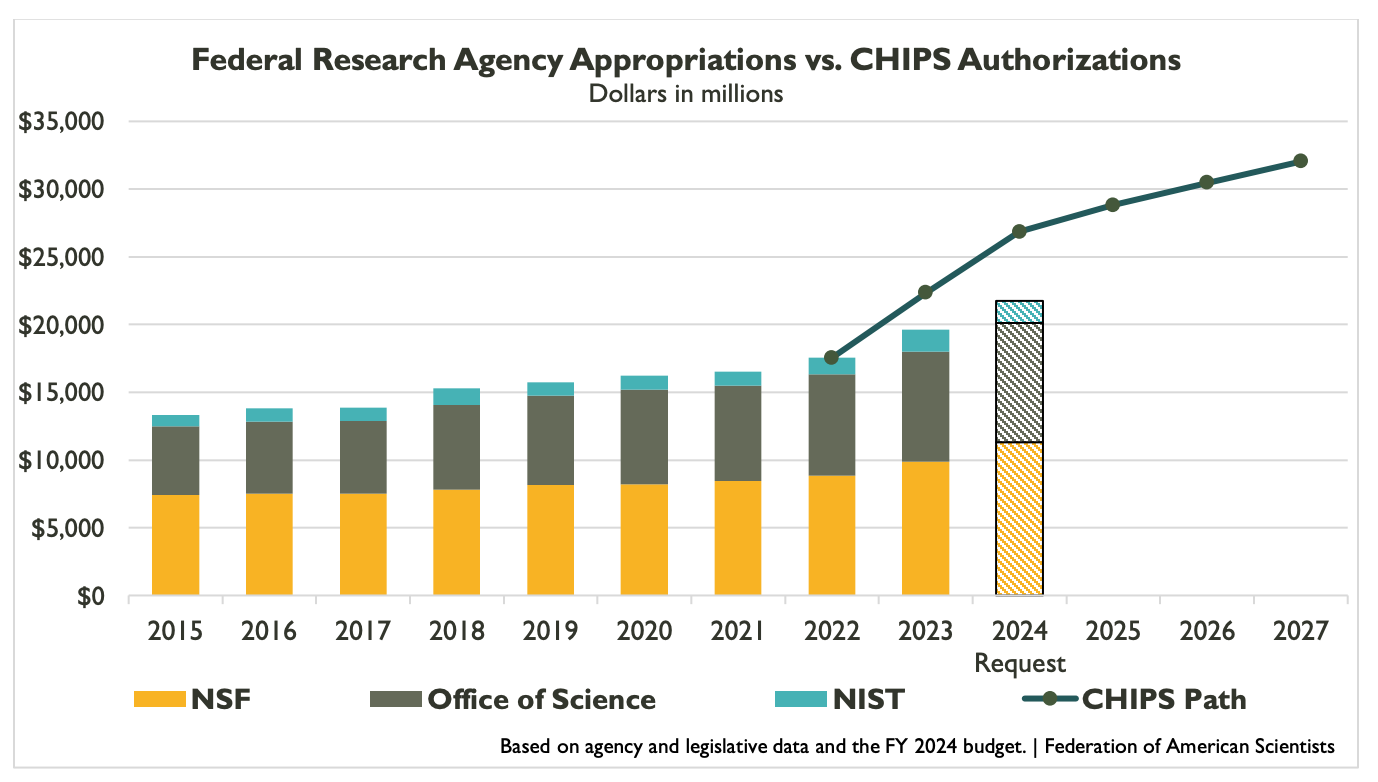

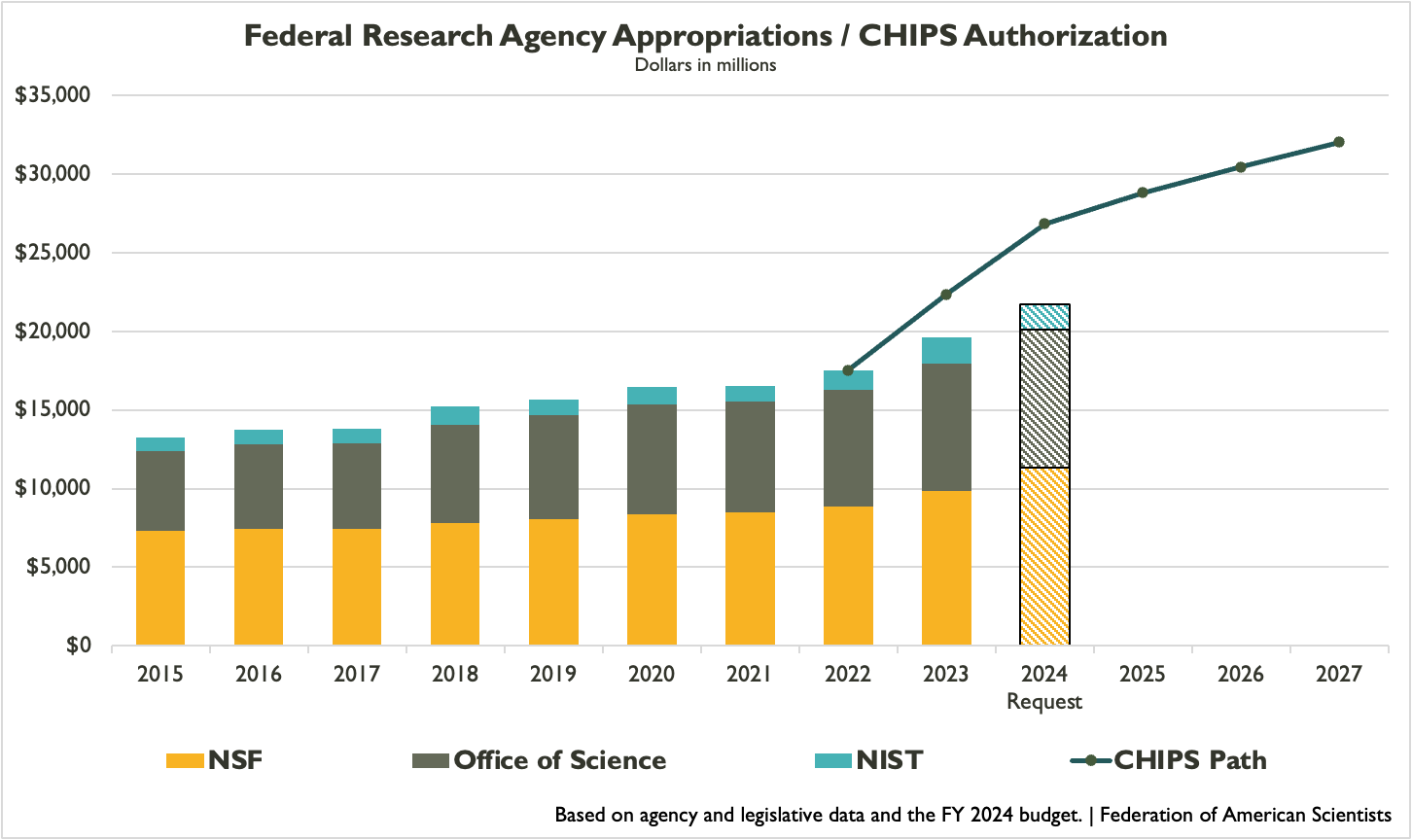

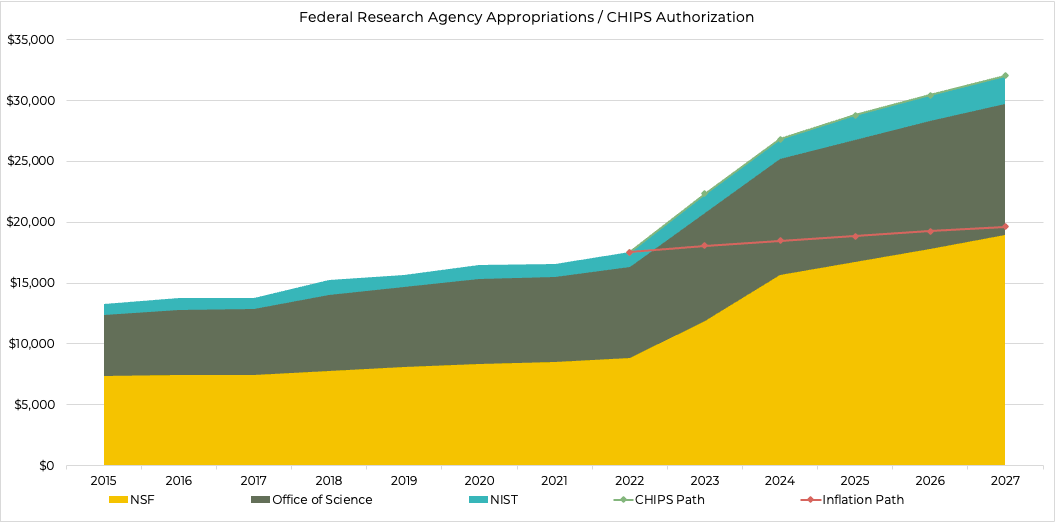

In the aggregate, CHIPS and Science authorized three research agencies – the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE SC), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) – to receive $26.8 billion in FY 2024 and $28.8 billion in FY 2025, representing substantial growth in both years. But appropriations have increasingly underfunded the CHIPS agencies, with a gap now over $8 billion (see graph).

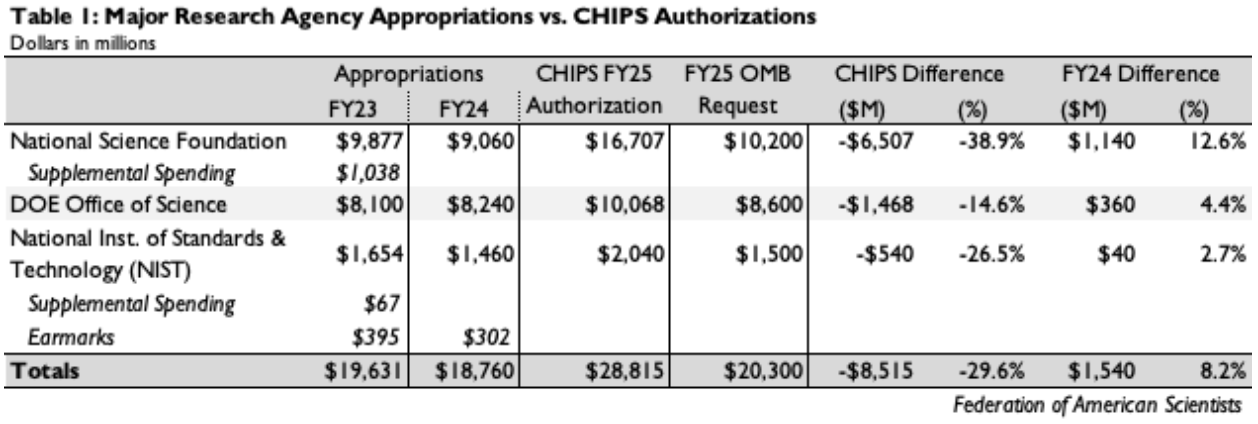

The table below shows agency funding data in greater detail, including FY 2023 and FY 2024 appropriations, the FY 2025 CHIPS authorization, and the FY 2025 request.

The National Science Foundation is experiencing the largest gap between CHIPS targets and actual appropriations following a massive year-over-year funding reduction in FY 2024. That cut is partly the result of appropriators rescuing NSF in FY 2023 with over $1 billion in supplemental spending to support both NSF base activities and implementation of the Technology, Innovation and Partnerships Directorate (TIP). While that spending provided NSF a welcome boost in FY 2023, it could not be replicated in FY 2024, and NSF only received a modest boost in base appropriations. As a result, the full year-over-decline for NSF amounted to over $800 million, which will likely mean cutbacks in both core and TIP (the exact distribution is to be determined though Congress called for an even-handed approach). It also means a CHIPS shortfall of $6.5 billion in both FY 2024 and FY 2025.

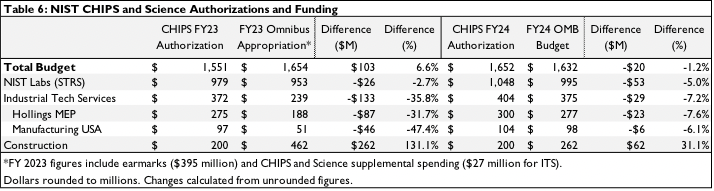

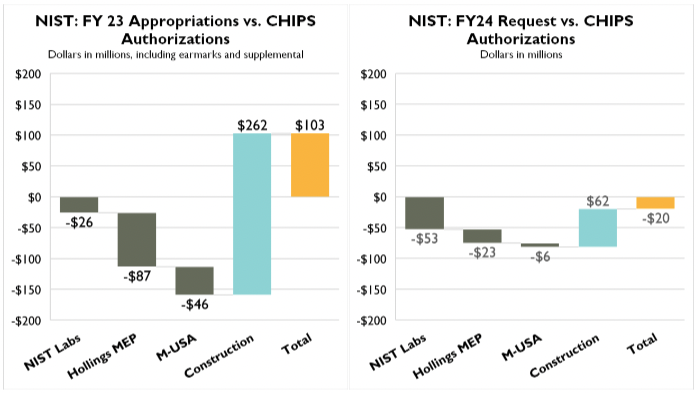

The National Institute of Standards and Technology also requires some additional explanation. Like NSF, NIST received some supplemental spending for both lab programs and industrial innovation in FY 2023, but NIST also has been subject to quite substantial earmarks in FY 2023 and FY 2024, as seen in the table above. The presence of earmarks in FY 2024 meant, in practice, a nearly $100 million reduction in funding for core NIST lab programs, which cover a range of activities in measurement science and emerging technology areas.

The Department of Energy’s Office of Science fared better than the other two in the omnibus with a modest increase, but still faces a $1.5 billion shortfall below CHIPS targets in the White House request.

Select Account Shortfalls

National Science Foundation

Core research. Excluding the newly-created TIP Directorate, purchasing power of core NSF research activities in biology, computing, engineering, geoscience, math and physical sciences, and social science dropped by over $300 million between FY 2021 and FY2023. If the FY 2024 funding cuts are distributed proportionally across directorates, their collective purchasing power would have dropped by over $1 billion all-in between FY 2021 and the present, representing a decline of more than 15%. This would also represent a shortfall of $2.9 billion below the CHIPS target for FY 2024, and will likely result in hundreds of fewer research awards.

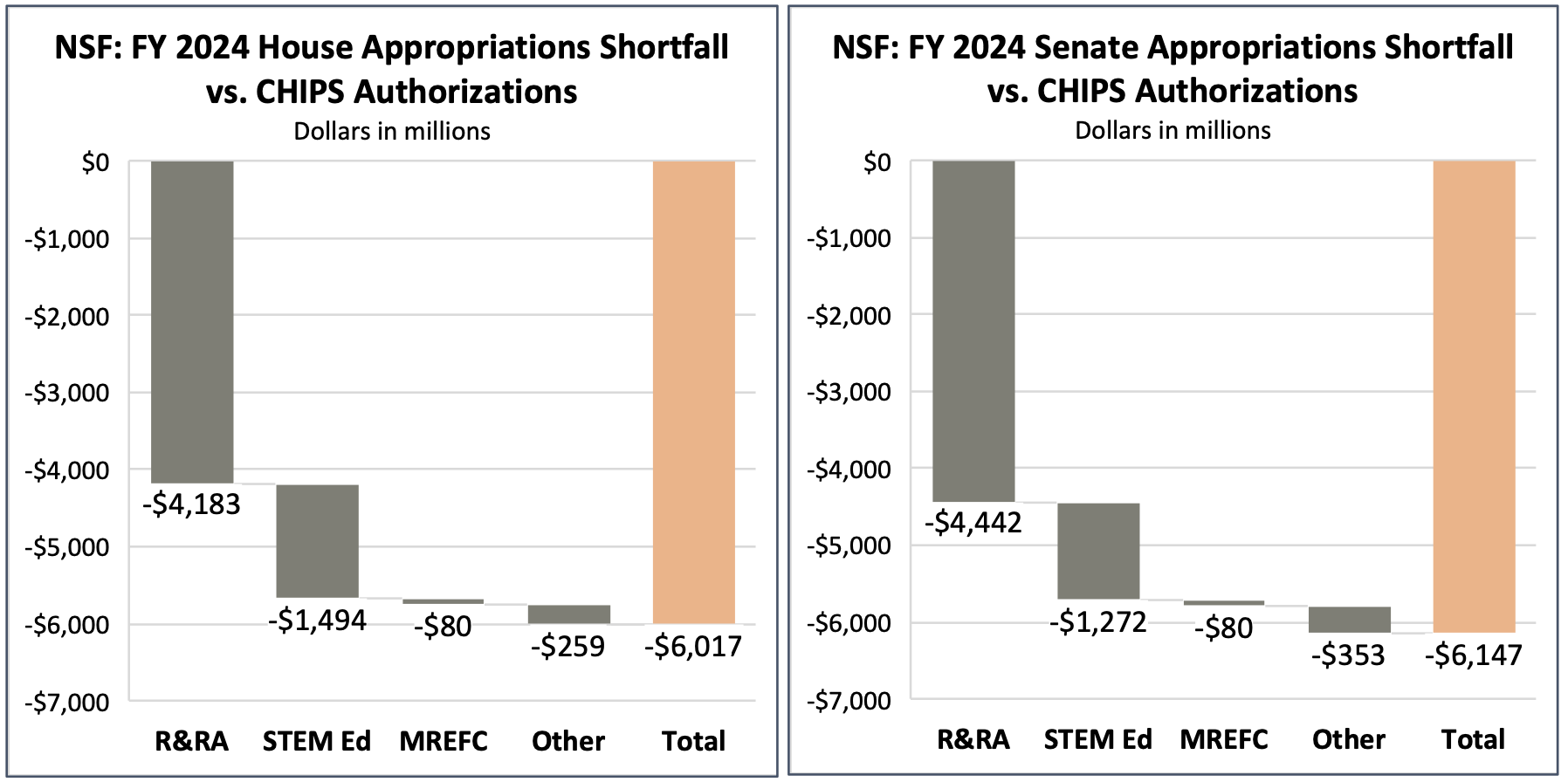

STEM Education. While not quite as large as core research, NSF’s STEM directorate has still lost over 8% of its purchasing power since FY 2021, and remains $1.3 billion below its CHIPS target after a 15% year-over-year cut in the FY 2024 omnibus. This cut will likely mean hundreds of fewer graduate fellowships and other opportunities for STEM support, let alone multimillion-dollar shortfalls in CHIPS funding targets for programs like CyberCorps and Noyce teacher scholarships. The minibus did allocate $40 million for the National STEM Teacher Corps pilot program established in CHIPS, but implementing this carveout will pose challenges in light of funding cuts elsewhere.

TIP Programs. FY 2023 funding fell over $800 million shy of the CHIPS target for the new technology directorate, which had been envisioned to grow rapidly but instead will now have to deal with fiscal retrenchment. Several items established in CHIPS remain un- or under-funded. For instance, NSF Entrepreneurial Fellowships have received only $10 million from appropriators to date out of $125 million total authorized, while Centers for Transformative Education Research and Translation – a new initiative intended to research and scale educational innovations – has gotten no funding to date. Also underfunded are the Regional Innovation Engines (see below).

Department of Energy

Microelectronics Centers. While the FY 2024 picture for the Office of Science (SC) is perhaps not quite as stark as it is for NSF – partly because SC didn’t enjoy the benefit of a big but transient boost in FY 2023 – there remain underfunded CHIPS priorities throughout. One more prominent initiative is DOE’s Microelectronics Science Research Centers, intended to be a multidisciplinary R&D network for next-generation science funded across the SC portfolio. CHIPS authorized these at $25 million per center per year.

Fission and Fusion. Fusion energy was a major priority in CHIPS and Science, which sought among other things expansion of milestone-based development to achieve a fusion pilot plant. But following FY 2024 appropriations, the fusion science program continues to face a more than $200 million shortfall, and DOE’s proposal for a stepped-up research network – now dubbed the Fusion Innovation Research Engine (FIRE) centers – remains unfunded. CHIPS and Science also sought to expand nuclear research infrastructure at the nation’s universities, but the FY 2024 omnibus provided no funding for the additional research reactors authorized in CHIPS.

Clean Energy Innovation. CHIPS Title VI authorized a wide array of energy innovation initiatives – including clean energy business vouchers and incubators, entrepreneurial fellowships, a regional energy innovation program, and others. Not all received a specified funding authorization, but those that did have generally not yet received designated line-item appropriations.

NIST

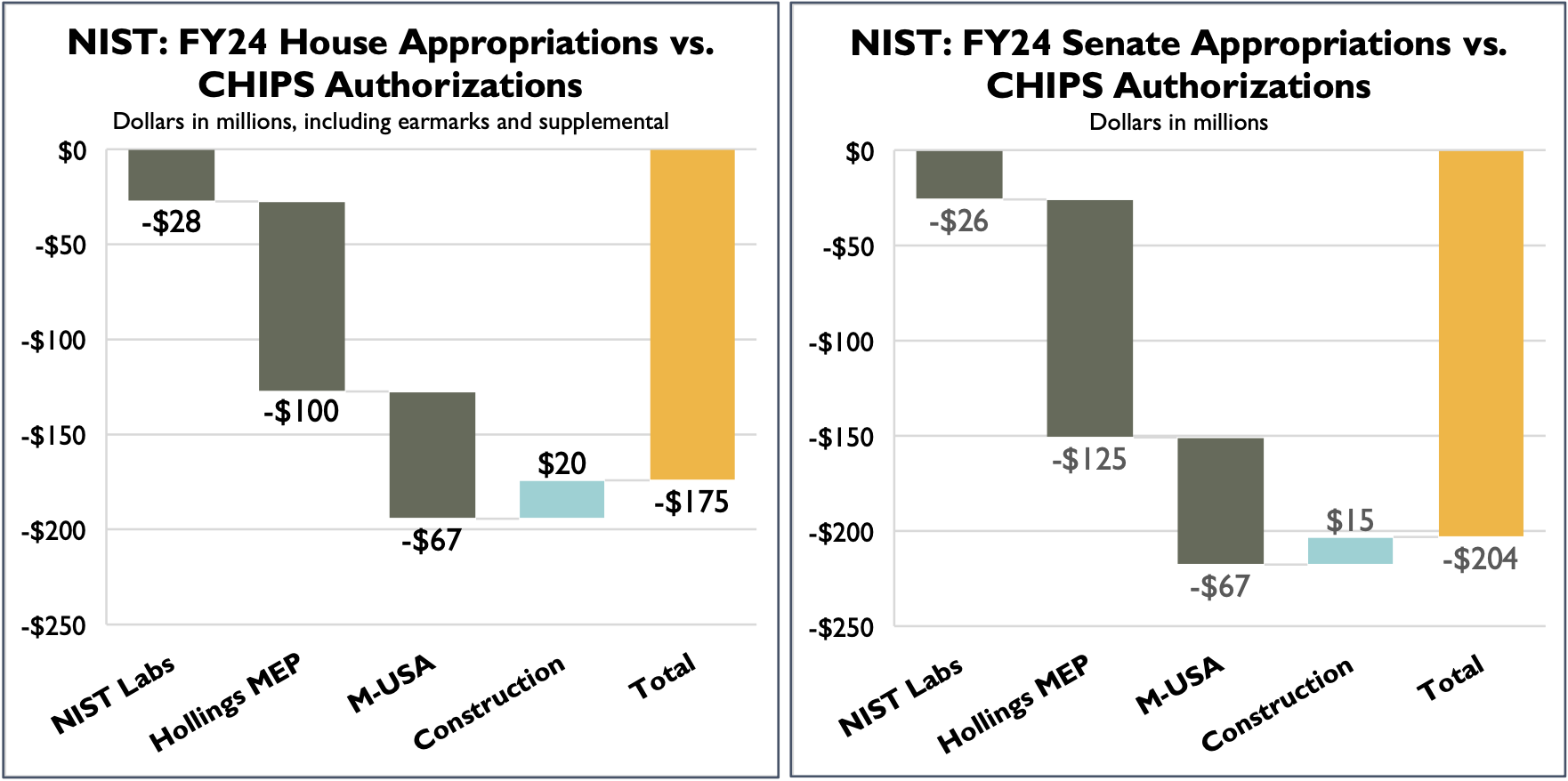

In addition to the funding challenges for NIST lab programs described above – which are critical for competitiveness in emerging technology – NIST manufacturing programs also continue to face shortfalls, of $192 million in the FY 2024 omnibus and over $500 million in the FY 2025 budget request.

Regional Innovation

As envisioned when CHIPS was signed, three major place-based innovation and economic development programs – EDA’s Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs (Tech Hubs), NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines (Engines), and EDA’s Distressed Area Recompete Pilot Program (Recompete) – would be moving from exclusively planning and selection into implementation phases as well in FY25. But with recent budget announcements, some implementation may need to be scaled back from what was originally planned, putting at risk our ability to rise to the confluence of economic and industrial challenges we face.

EDA Tech Hubs. In October 2023, the Biden-Harris administration announced the designation of 31 inaugural Tech Hubs and 29 recipients of Tech Hubs Strategy Development Grants from nearly 400 applicants. These 31 Tech Hubs designees were chosen for their potential to become global centers of innovation and job creators. Upon announcement, the designees were then able to apply to receive implementation grants of $40-$70 million to each of approximately 5-10 of the designated Tech Hubs. Grants are expected to be announced in summer 2024.

The FY 2025 budget request for Tech Hubs includes $41 million in discretionary spending to fund additional grants to the existing designees, and another $4 billion in mandatory spending – spread over several years – to allow for additional Tech Hubs designees and strategy development grants. CHIPS and Science authorized the Hubs at $10 billion in total, but the program has only received 5% of this in actual appropriations to date. The FY25 request would bring total program funding up to 46% of the authorization.

The ambitious goal of Tech Hubs is to restore the U.S. position as a leader in critical technology development, but this ambition is dependent on our ability to support the quantity and quality of the program as originally envisioned. Without meeting the funding expectations set in CHIPS, the Tech Hubs’ ability to restore American leadership will be vastly limited.

NSF Engines. In January 2024, NSF announced the first NSF Engines awards to 10 teams across the United States. Each NSF Engine will receive an initial $15 million over the next two years with the potential to receive up to $160 million each over the next decade.

Beyond those 10 inaugural Engines awards, a selection of applicants were invited to apply for NSF Engines development awards, with each receiving up to $1 million to support team-building, partnership development, and other necessary steps toward future NSF Engines proposals. NSF’s initial investment in the 10 awardee regions is being matched almost two to one in commitments from local and state governments, other federal agencies, private industry, and philanthropy. NSF previously announced 44 Development Awardees in May 2023.

To bolster the efforts of NSF Engines, NSF also announced the Builder Platform in September 2023, which serves as a post-award model to provide resources, support, and engagement to awardees.

The FY25 request level for NSF Engines is $205 million, which will support up to 13 NSF Regional Innovation Engines. While this $205 million would be a welcome addition – especially in light of the funding risks and uncertainty in FY24 mentioned above – total funding to date is considerably below CHIPS aspirations, accounting for just over 6% of authorized funding.

EDA Recompete. The EDA Recompete Program, authorized for up to $1 billion in the CHIPS and Science Act, aims to allocate resources towards economically disadvantaged areas and create good jobs. By targeting regions where prime-age (25-54 years) employment lags behind the national average, the program seeks to revitalize communities long overlooked, bridging the gap through substantial and flexible investments.

Recompete received $200 million in appropriations in 2023 for the initial competition. This competition received 565 applications, with total requests exceeding $6 billion. Of those applicants, 22 Phase 1 Finalists were announced in December 2023.

Recompete Finalists are able to apply for the Phase 2 Notice of Funding Opportunity and are provided access to technical assistance support for their plans. In Phase 2, EDA will make approximately 4-8 implementation investments, with awarded regions receiving between $20 to $50 million on average.

Alongside the 22 Finalists, Recompete Strategy Development Grant recipients were announced. These grants support applicant communities in strategic planning and capacity building.

Following a shutout in FY 2024 appropriations, Recompete funding in the FY25 request is $41 million, bringing total funding to date to $241 million or just over 24% of authorized funding.

Congress will soon have the chance to rectify these collective shortfalls, with FY 2025 appropriations legislation coming down the pike soon. But the November elections throw substantial uncertainty over what was already a difficult situation. If Congress can’t muster the votes necessary to properly fund CHIPS and Science programs, U.S. competitiveness will continue to suffer.

CHIPS and Science: FY24 Research Appropriations Short by Over $7 Billion

When Congress adopted the CHIPS and Science Act (P.L. 117-167) in 2022 on a bipartisan basis, it was intended to strengthen the United States’ ability to compete and to invest in solutions for national challenges. Beyond semiconductors, CHIPS and Science took an array of concrete steps to strengthen innovation: it provided strategic focus for the federal R&D enterprise, created investments in U.S. workers and regions, expanded the funding toolkit, and authorized boosts for science and education across the spectrum.

Such a varied approach is critical in the race for technological and economic advantage, as other nations mount challenges to U.S. leadership – particularly China, which has seized the lead in several key technology areas after years of accelerated investment. But despite this impetus, appropriations for research agencies have fallen quite short of the CHIPS and Science targets. Following an FY 2023 omnibus shortfall of nearly $3 billion, FY 2024 appropriations to date for research agencies are approximately $7.5 billion below authorized levels (see graph).

This report provides a detailed breakdown of accounts and programs for these agencies and compares current appropriations against those authorized by CHIPS and Science, as a reference and resource for policymakers and advocates.

CHIPS and Science Background

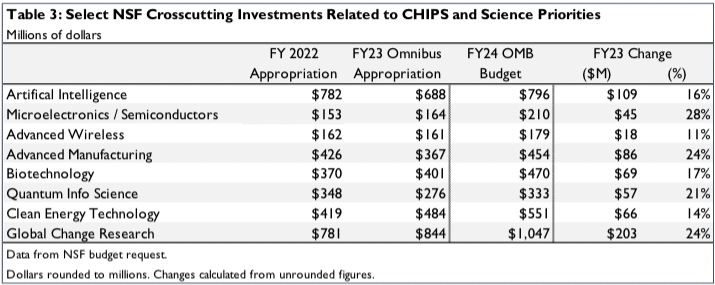

CHIPS and Science took manifold steps to strengthen the U.S. science enterprise. A conceptual throughline is the establishment of key technology focus areas and societal challenges defined in Section 10387, shown in the table below. While not the only priorities for federal R&D, these focus areas provide a framework to guide certain investments, particularly those by the National Science Foundation’s new technology directorate.

These key technology areas are also relevant for long-term strategy development by the Office of Science and Technology Policy and the National Science and Technology Council, as directed by CHIPS and Science. Several of the technology areas also appear on the Defense Department’s Critical Technologies list.

While much of the focus has been on semiconductors, the activities covered in this report constitute the bulk of the “and Science” portion of CHIPS and Science. While a full index of all provisions is not the goal here, it’s worth remembering the sheer variety of activities authorized in CHIPS and Science, which cut across areas including:

- Fundamental science and curiosity-driven research funded by science agencies at federal labs, universities, and companies. CHIPS and Science covered multiple disciplines but has a particular emphasis on the physical sciences, math and computer science, and engineering. Several of these disciplines have fallen dramatically within the federal portfolio in recent decades.

- Use-inspired research, translation, and production. Elements of CHIPS and Science sought to expand the ability of federal agencies to make strategic investments in emerging technologies, move new advances through the innovation chain, and work with external partners to enable the manufacture of new technologies and strengthen supply chains.

- Regional innovation. A major element of the above is emphasis on expanding the geographic footprint of federal investment, most notably through the new Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs program. The program received $500 million out of an authorized $10 billion in the FY 2023 omnibus.

- STEM education and workforce. The Act expands or creates numerous programs to foster STEM skills, opportunity and experience among students and young researchers, including through entrepreneurial fellowships, student and educator support, and apprenticeships and worker upskilling initiatives.

- Research facilities and instrumentation at national labs and universities across the country, including modernization of aging infrastructure, construction of cutting-edge user facilities, and grants for mid- scale research infrastructure projects.

Aggregate Agency Appropriations

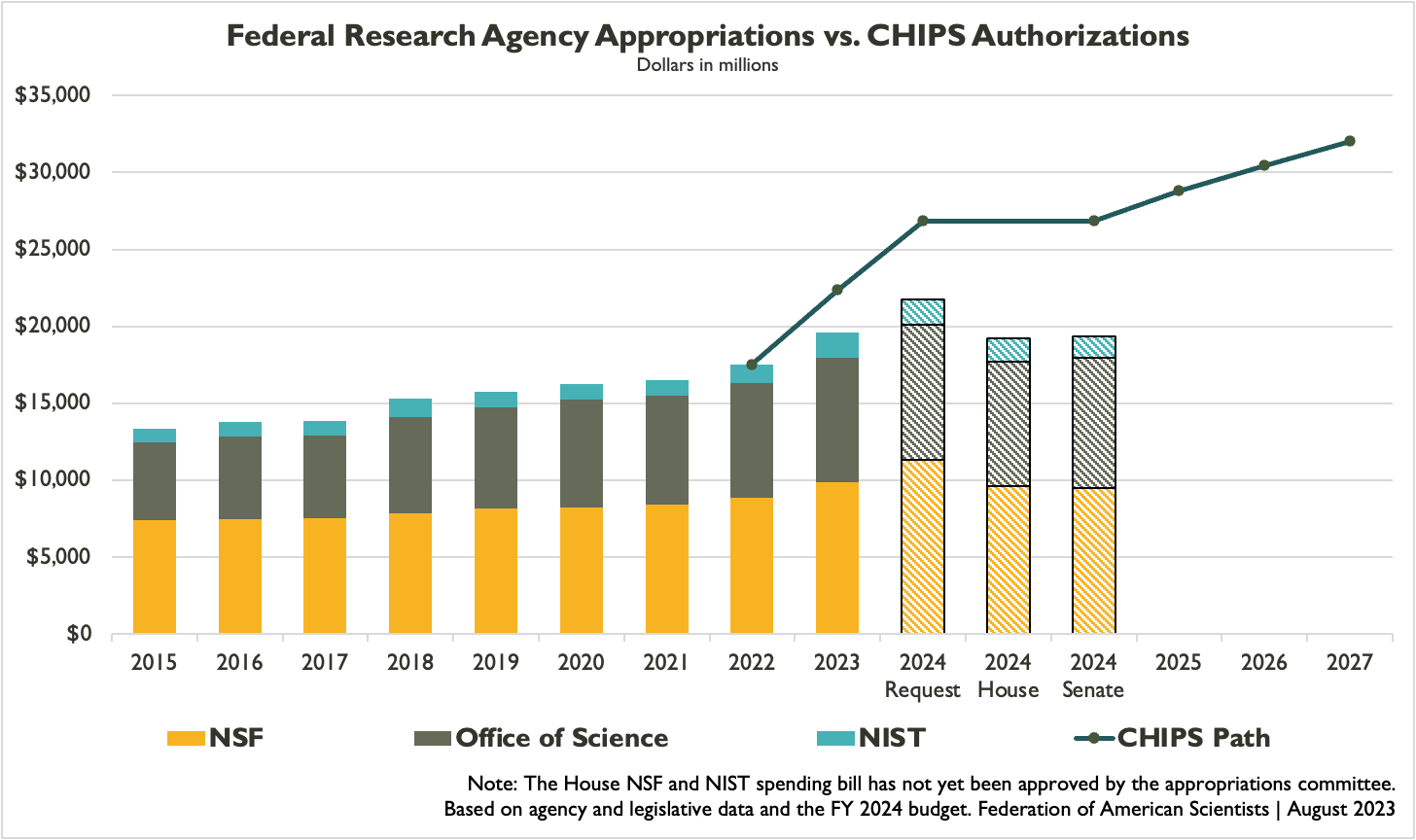

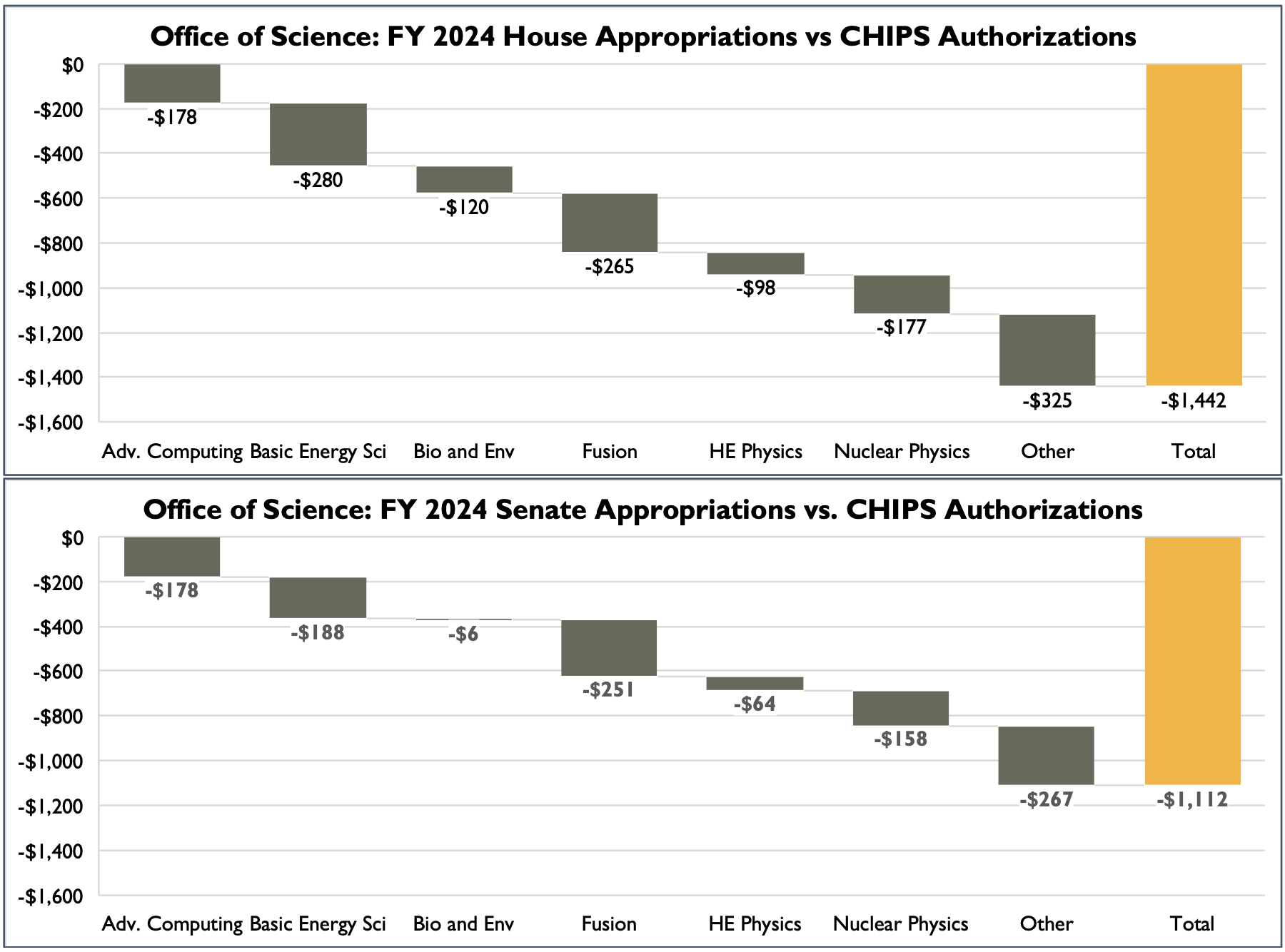

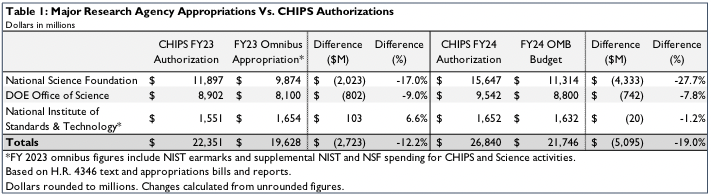

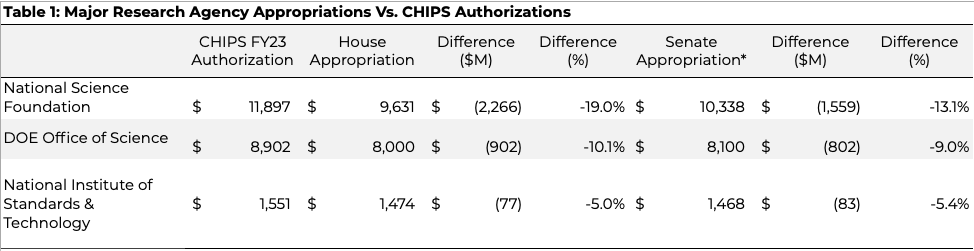

In the aggregate, CHIPS and Science authorized three research agencies – the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE SC), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) – to receive $26.8 billion in FY 2024, a $4.5 billion boost from the FY 2023 authorizations. House and Senate appropriations to this point – including the House Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies bill, which was not adopted by the Appropriations Committee before the August break – amount to somewhat above $19 billion in both, representing a more than $7 billion or approximately 28% shortfall, in each (see Table 1 below). In fact, these aggregates represent not only a shortfall below the FY 2024 authorization, but a reduction of $250 million and $421 million, respectively, below FY 2023 appropriations, when factoring in FY 2023 NSF and NIST funding provided as supplemental.

The gap for NIST grows larger when accounting for earmarks, which amounted to approximately $119 million in the House and $199 million in the Senate. Excluding earmarks, the NIST appropriation totals for FY 2024 result in shortfalls below the authorization of $294 million or 18% in the House, and $403 million or 24% in the Senate.

Agency Breakdowns

National Science Foundation

NSF is at the core of the CHIPS and Science goals in manifold ways. It boasts a long-term track record of excellence in discovery science at U.S. universities and is the first or second federal funder of research in several tech-relevant science and engineering disciplines. It also seeks to boost the talent pipeline by engaging with underserved research institutions and student populations, supporting effective STEM education approaches, and providing fellowships and other opportunities to students and teachers.

CHIPS and Science also expanded NSF’s ability to drive technology, innovation, and advanced manufacturing, augmenting existing innovation programs like the Engineering Research Centers and the Convergence Accelerators with new activities like the Regional Innovation Engines.

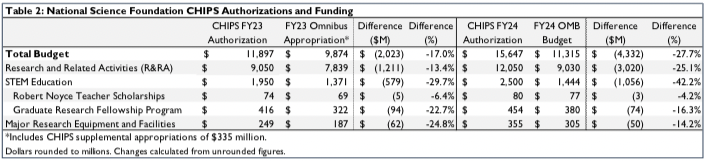

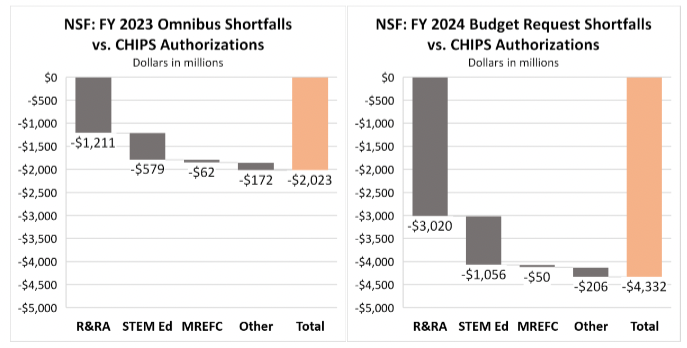

As seen in Table 2, the FY 2024 appropriations for NSF are roughly $6 billion or 39% below the CHIPS and Science authorization. The agency toplines are also 2.5% and 3.8% below FY 2023 figures in total, including FY 2023 supplemental spending.

In both the House and the Senate, FY24 Appropriations fall far short of CHIPS authorizations across research and education accounts.

Research & Related Activities (R&RA). R&RA is the primary research account for NSF, supporting grants, centers, instrumentation, data collection, and other activities across seven research directorates including the new Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships (TIP) directorate. These directorates play a foundational role in driving U.S. leadership in biology, computing and information science, engineering, geoscience, math and computer science, and social science, as well as integrated and international programs. R&RA can likely absorb substantial additional funding: the agency must routinely leave thousands of high-scoring grant proposals on the table for lack of funding. For instance, in FY 2021, NSF had to leave unfunded over 4,000 proposals amounting to $4.1 billion ranked “Very Good” or better.

In report language, Senate appropriators encourage NSF to initiate a contract with the National Academies to pursue a CHIPS and Science-mandated assessment of the key technology focus areas. For FY 2024, Senate appropriators have provided the same funding as FY 2023 for the Regional Innovation Engines, quantum information science activities, and AI research. The EPSCoR program received $275 million, a $20 million increase. House appropriators have not yet released appropriations report language for NSF.

STEM Education. The Directorate for STEM Education houses NSF activities across K-12, tertiary education, learning in informal settings, and outreach to underserved communities. CHIPS and Science authorized increased funding for multiple individual programs including Graduate Research Fellowships, Robert Noyce Teacher Fellowships Program, CyberCorps, and the new Centers for Transformative Education Research and Translation, among others. These programs serve an array of functions, including STEM teacher recruitment, support for the federal cybersecurity workforce, and support for a range of learners and institutions including veterans and underrepresented minorities.

Senate appropriators provided a mix of small changes, flat funding, or trims from FY 2023 levels to several NSF STEM programs including graduate and Noyce fellowships, the HBCU Undergraduate Program and the Centers for Research Excellence in Science and Technology (CREST). In most cases these figures were all well short of CHIPS and Science targets. Notably, Senate appropriators provided $40 million for a National STEM Teacher Corps pilot program and encouraged NSF to establish a Centers for Transformative Education Research and Translation, both authorized in CHIPS and Science.

Department of Energy Office of Science

The Office of Science (SC) is the largest funder of the physical sciences including chemistry, physics, and materials, all of which contribute to the technology priorities in CHIPS and Science. In addition to funding Nobel prizewinning basic research and large-scale science infrastructure, the Office also funds workforce development, use-inspired research, and user facilities that provide tools for tens of thousands of users each year, including hundreds of small and large businesses that use these services to drive breakthroughs. More than two thirds of SC-funded R&D is performed at national labs. SC also supports workforce development and educational activities for students and faculty to expand skills and experience.

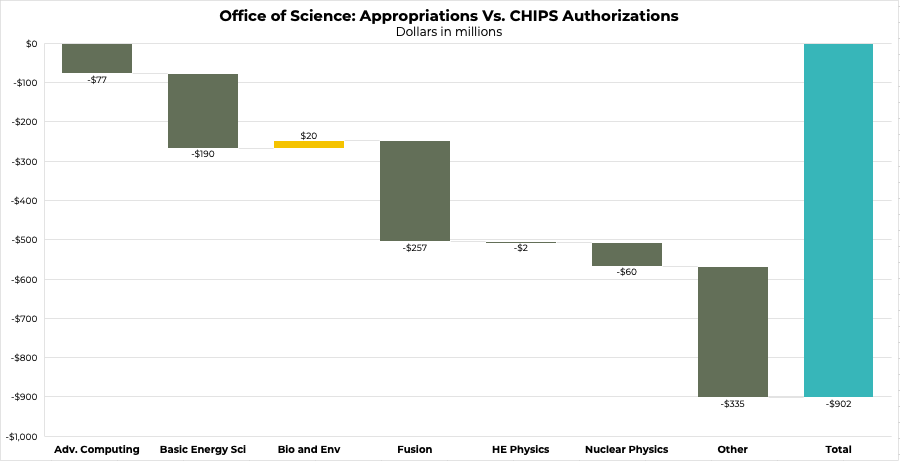

As seen in Table 3, topline FY 2024 appropriations have been over $1 billion or at least 12% short of the CHIPS authorization in both chambers. House appropriations have been flat from the FY 2023 omnibus while Senate appropriators have provided SC with a 4% increase overall.

Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) funds research in AI, computational science, mathematics, and networking. Among CHIPS and Science priorities, ASCR will begin to establish a dedicated Quantum Network along with other research, testbeds, and applications in FY 2024. CHIPS and Science authorized $31.5 million in FY 2024 for the QUEST Act, to give U.S. researchers access to quantum hardware and research cloud resources, while House appropriators have provided up to $15 million. CHIPS also authorized $100 million for provision of quantum network infrastructure. Senate appropriators directed DOE to provide an update on its plan to sustain U.S. leadership in advanced computing including in AI, zettascale computing, and quantum computing.

Basic Energy Sciences (BES), the largest SC program, supports fundamental science disciplines with relevance for several CHIPS technology areas including materials, microelectronics, AI, and others, as well as extensive user facilities and other novel initiatives. CHIPS and Science authorizations for FY 2024 included research and innovation hubs related to artificial photosynthesis ($100 million) and energy storage ($120 million). Both committees funded the innovation hubs on these topics at $20 million and $25 million, respectively. CHIPS also authorized $50 million per year for carbon materials and storage research in coal-rich U.S. regions.

Biological and Environmental Research (BER) supports research in biological systems science including genomics and imaging, and in earth systems science and modeling. BER programs have fared quite differently in appropriations, with House appropriators reducing funding by $82 million or 9% below FY 2023 omnibus levels, while BER would receive a $32 million or 4% boost in the Senate.

Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) supports research into matter at high densities and temperatures to lay the groundwork for fusion as a future energy source. Appropriations thus far have provided far less than requested for public-private partnerships to support and expand the domestic fusion industry. The Milestone-Based Development Program, to develop technology roadmaps and achieve progress toward fusion pilot plants, would receive $35 million in the House and not less than $25 million in the Senate, versus a combined request of $135 million for the milestone program and the Innovation Network for Fusion Energy (INFUSE) program, which enables industry partnerships with national labs and American universities.

Energy Earthshots are a crosscutting DOE initiative to tackle challenges at the nexus of basic and applied R&D through multidisciplinary team science, thus enabling DOE to better achieve progress in the CHIPS- identified advanced energy technology focus area. Appropriations thus far would dramatically scale back SC’s Earthshot investments from FY 2023 levels. House appropriators would provide $20 million and Senate appropriators $67 million for SC’s portion of the Earthshot initiative, versus FY 2023 funding of $100 million and an FY 2024 request level of $175 million. Ongoing Earthshots address hydrogen, energy storage, carbon removal, enhanced geothermal, offshore wind, industrial heat, and clean fuels, with additional projects anticipated in FY 2024.

Quantum Information Science is a priority for both CHIPS and Science and in the Administration’s request, but appropriations remain limited. House appropriators have provided not less than $245 million, same as the FY 2023 omnibus level, while the Senate provided a $10 million or 4% increase.

National Institute of Standards and Technology

While smaller than the other agencies covered here, NIST plays a critical role in the U.S. industrial ecosystem as the lead agency in measurement science and standards-setting, as well as funder of world-class physical science research and user facilities. NIST R&D activities cover several CHIPS And Science technology priorities including cybersecurity, advanced communications, AI, quantum science, and biotechnology. NIST also boasts a wide-ranging system of manufacturing extension centers in all 50 states and Puerto Rico, which help thousands of U.S. manufacturers grow and innovate every year.

As seen in Table 4, the NIST appropriation – which doesn’t include mandatory semiconductor funding – is 11% to 12% below the CHIPS and Science level for FY 2024. These figures include earmarks of $119 million and $199. Excluding earmarks, the NIST shortfalls are 18% in the House and 24% in the Senate.

Scientific and Technical Research Services (STRS) is the account for NIST’s national measurement and standards laboratories, which pursue a wide variety of CHIPS and Science-relevant activities in cybersecurity, AI, quantum information science, advanced communications, engineering biology, resilient infrastructure, and other realms. STRS also funds two user facilities, the NIST Center for Neutron Research and the Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology.

Excluding FY 2024 House and Senate earmarks, NIST lab programs would receive cuts of approximately $50 million under current appropriations.

House report language for NIST has not yet been adopted, but Senate appropriators approved the requested $5 million increase for quantum information science, while providing cybersecurity funding no less than FY 2023 levels and holding AI research flat at FY 2023 enacted levels. Critical and emerging technology investments received a $12 million increase versus the requested $20 million boost.

Industrial Technology Services is the overarching account funding the Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) and the Manufacturing USA innovation network. As can be seen in Table 4, these programs collectively faced a much greater authorization shortfall than NIST lab programs.

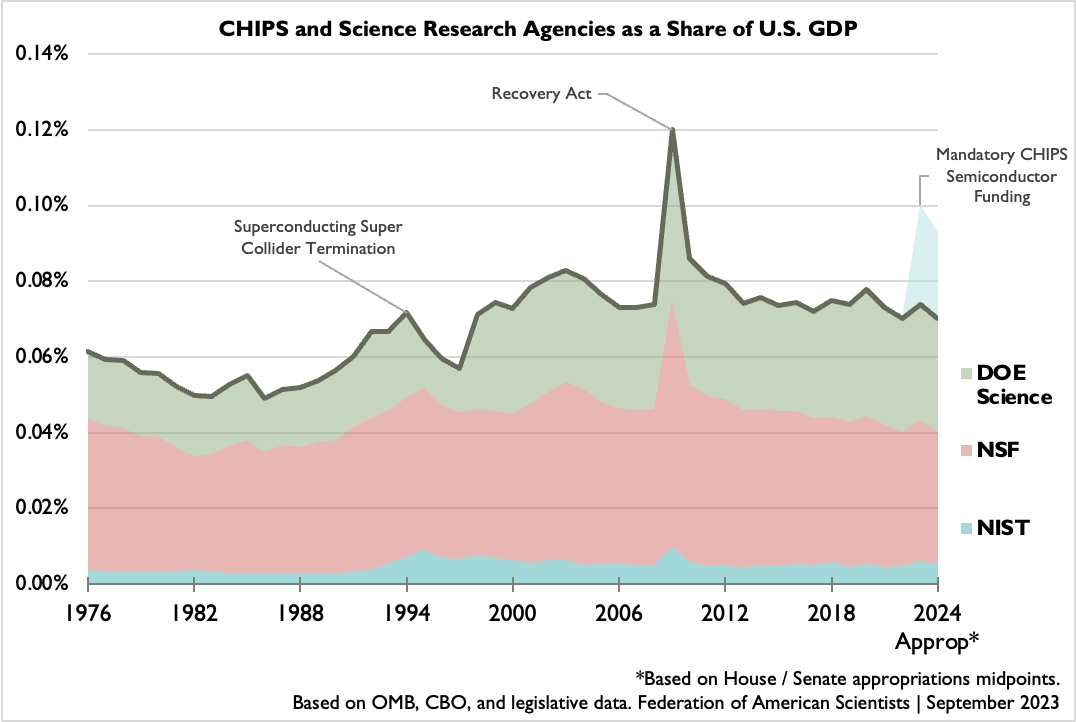

Appropriations in Historical Context

Relative funding for NSF, SC and NIST has evolved over the decades, as seen in the graph on the following page. As a share of the U.S. economy, funding for the three agencies experienced marked decline in the late 1970s and early 1980s, dropping to 0.05% of U.S. GDP in the mid-1980s. Beginning in the later Reagan era and continuing into the Clinton era, the three agencies experienced a recovery and rise through the late 1990s tech bubble.

After peaking in FY 2003 at 0.083 percent of GDP, the three agencies have undergone a period of relative funding stagnation. Apart from the transient Recovery Act funding spike, agencies’ combined funding has wavered around 0.075% of GDP. Much of this stagnant is due to the discretionary caps under the Budget Control Act, which took effect beginning in FY 2012.

CHIPS and Science provided NIST mandatory funding specifically earmarked for semiconductor R&D and industry incentives but left the range of other technology priorities to be funded through annual discretionary appropriations, which as described have been limited. Under current appropriations, agency discretionary budgets would likely drop to near 0.07% of U.S. GDP, their lowest point in 25 years.

The bold vision of the CHIPS and Science Act isn’t getting the funding it needs

Originally published May 17, 2023 in Brookings.

The legislative accomplishments of the previous session of Congress have given advocates of more robust innovation and industrial development investments much to be excited about. This is especially true for the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS), which committed the nation not just to compete with China over industrial policy and talent, but to advance broad national goals such as manufacturing productivity and economic inclusion while ramping up federal investment in science and technology.

Most notably, CHIPS authorized rising spending targets for key anchors of the nation’s innovation ecosystem, including the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). In that regard, the act’s passage was a breakthrough—including for an expanded focus on place-based industrial policy.

However, it’s become clear that this breakthrough is running into headwinds. In spite of ongoing rhetorical support for the act’s goals from many political leaders, neither the FY 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act nor the Biden administration’s FY 2024 budget request have delivered on the intended funding targets. This year’s omnibus funding remained nearly $3 billion short of the authorized levels for research agencies, while the 2024 budget request undershoots agency targets by over $5 billion. And with the debt ceiling crisis coming to a head this month—and House legislation on the table that would substantially roll back federal spending—it’s even harder to be optimistic about the odds of fulfilling the CHIPS and Science Act’s vision of resurgent investment in American competitiveness.

Instead, delivery on the CHIPS and Science Act paradigm can only be fractional as of now, with a $3 billion (and growing) funding gap for research and less than 10% of the five-year place-based vision funded to date.

All of which underscores how much work remains to be done if the nation is going to deliver on the promise of a rejuvenated innovation and place-based industrial strategy. Leaders need to make an energetic and bipartisan reassertion of the CHIPS vision without delay if the government is to truly follow through on its bold promises.

CHIPS has a broad, Innovative policy menu to support renewed American Competitiveness

Recently, Rep. Frank Lucas (R-Okla.), chair of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, rightly pointed out that the “science” portion of the CHIPS and Science Act (i.e., separate from its subsidies for semiconductor factories) will be “the engine of America’s economic development for decades to come.” One way the act seeks to achieve this is by creating the Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships at NSF, and focusing it on an evolving set of technological and social priorities (see Tables 1a + 1b). These won’t just drive NSF technology work, but will guide the development of a more concerted whole-of-government strategy.

| Table 1b: Societal, national, and geostrategic challenges | |

|---|---|

| U.S. national security | Climate change and sustainability |

| Manufacturing and industrial productivity | Inequitable access to education, opportunity, services |

| Workforce development and skill gaps | |

In light of these priorities, it’s no mistake that Congress placed the NSF, the Energy Department’s Office of Science, NIST, and the Economic Development Administration (EDA) at the core of the “science” portion of the act. The first three agencies are major funders of research and infrastructure for the physical science and engineering disciplines that undergird many of these technology areas. The EDA, meanwhile, is the primary home for place-based initiatives in economic development.

Meanwhile, in keeping with the larger strategy of countering the nation’s science and technology drift, Congress adopted five years of rising “authorizations” for these core innovation agencies. However, it bears remembering that these authorizations are not actual funding, but multiyear funding targets that, if fully funded year by year, would result in an aggregate budget doubling. In short, Congress has declared that the national budget for science and technology should go up, not down, over the next five years.

It’s also worth noting that the act seeks to boost investment in many different areas, including:

- Fundamental science and curiosity-driven research funded by science agencies at federal labs, universities, and companies.

- Use-inspired research, translation, and production to expand the ability of federal agencies to invest in emerging technology, enter partnerships, and drive manufacturing innovation.

- STEM education and workforce development to create or expand programs to foster opportunities and up-skilling.

- Research facilities and instrumentation at national labs and universities across the country, including modernization of aging research infrastructure.

- Regional innovation to broaden the nation’s innovation map.

The upshot: Supporters are not wrong in seeing the CHIPS and Science Act as a major moment of aspiration for U.S. innovation efforts and ecosystems.

Government Appropriations are falling short on CHIPS funding by billions of dollars

Yet for all the act’s valuable programs and focus areas, not all is well. As of now, there have been two rounds of proposed or adopted funding policy for CHIPS research agencies—and the results are mixed to disappointing as details a new funding update on the CHIPS and Science Act from the Federation of American Scientists.

The first funding round was the FY 2023 omnibus package Congress adopted last December. There, the aggregate appropriations for the NSF, Office of Science, and NIST amounted to $2.7 billion—a 12% shortfall below the aggregate FY 2023 target of $22.4 billion.

Table 2: Major research agency appropriations vs. CHIPS authorizations

| CHIPS FY23 Authorizations | FY23 Omnibus Appropriation* | Difference ($M) | Difference (%) | CHIPS FY24 Authorizations | FY24 OMB Budget | Difference ($M) | Difference (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Science Foundation | $11,897 | $9,874 | ($2,023) | -17.0% | $15,647 | $11,314 | ($4,333) | -27.7% |

| DOE Office of Science | $8,902 | $8,100 | ($802) | -9.0% | $9,542 | $8,800 | ($742) | -7.8% |

| National Institute of Standards & Technology | $1,551 | $1,654 | $103 | 6.6% | $1,652 | $1,632 | ($20) | -1.2% |

| Totals | $22,351 | $19,628 | ($2,723) | -12.2% | $26,840 | $21,746 | ($5,095) | -19.0% |

| Dollars in millions | *FY23 omnibus figures include NIST earmarks and supplemental NIST and NSF spending for CHIPS and Science activities | |||||||

Then, in March, amid what was already a yawning funding gap, the White House released its FY 2024 budget proposal. That proposal would have the three CHIPS research agencies falling further behind: $5.1 billion, or 19% below the act’s authorization.

In both the omnibus and the budget, NSF funding was the biggest miss. This can be divided into a few segments:

- Core research directorates. Most NSF science research is channeled through six research directorates that focus on biology, computing and information science, engineering, geoscience, math and computer science, or social science, alongside offices focused on multiple crosscutting activities. This research lays a foundation for innovative advances and funds several mechanisms for industrial research partnerships, roughly in line with the CHIPS and Science Act’s broader industrial innovation goals. Funding for these collective activities stood at about $591 million (8% below the authorized level) in FY 2023 and $846 million (10% below the authorized level) in the FY 2024 budget request.

- Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP). This new directorate established in CHIPS is meant to support translational, use-inspired, and solutions-oriented research and development through a variety of novel modes and models, including the NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines (more on these below), translation accelerators, entrepreneurial fellowships, and test beds. Authorizers set a TIP funding target of $1.5 billion in FY 2023 and $3.4 billion in FY 2024—the most ambitious CHIPS appropriations targets by far. However, actual funding was $620 million short in FY 2023 and $2.2 billion short in the FY 2024 budget request.

- STEM education. The NSF’s Directorate for STEM Education houses activities across K-12 education, tertiary education, informal learning settings, and outreach to underserved communities. CHIPS authorized boosts for multiple directorate programs, including Graduate Research Fellowships, Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarships, and CyberCorps Scholarships, while establishing new Centers for Transformative Education Research and Translation to conduct education research and development. Collectively, these STEM education activities fell $579 million short of their $1.4 billion authorized level in the FY 2023 omnibus, and $1.1 billion short in the FY 2024 budget request.

With these shortfalls at NSF and other agencies, it will be difficult for federal science and innovation programs to have the transformative impact that CHIPS envisioned.

Funding for place-based industrial policy programs is also coming up short

In addition to decreased agency support, actual funding for what we call the “place-based industrial policy” in the CHIPS and Science Act is also coming up short, by even greater relative margins. Where the agency research funding gaps are a substantial restraint on innovative capacity, the diminished place-based funding is an out-and-out emergency.

These programs are important because after years of uneven economic progress across places, CHIPS saw Congress finally accelerating large-scale, direct investments to unlock the innovation potential of underdeveloped places and regions. Thanks to some of those investments, including several new challenge grants, scores of state and local leaders across the country have thrown themselves headlong into the design of ambitious strategies for building their own innovation ecosystems.

Yet for all of the legitimate excitement and interest of stakeholders in literally every state, the numbers that permit actual implementation are not all good. Looking at several of the most visible new place-based programs, the funding news is so far mixed to outright disappointing.

- Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs: Authorized at $10 billion over five years, the program received just $500 million in the FY 2023 omnibus—one-quarter of its authorized level for the year. This has greatly limited the resources available to the EDA for “development” grants to build out the program’s 20 forecasted hubs. Currently, the EDA is planning to make only five to 10 much smaller development grants instead of the authorized 20 very large grants, with more uncertainty ahead. Meanwhile, a $4 billion request in the president’s FY 2024 budget for mandatory funding outside the normal appropriations process (as opposed to discretionary spending, which is funded through annual spending bills) faces long odds.

- Regional Innovation Engines: This NSF program received $200 million in FY 2023 appropriations, and would receive $300 million under the FY 2024 request. It was authorized somewhat differently than other CHIPS line items, receiving a joint $6.5 billion authorization over five years for the Engines along with NSF’s newly authorized Translation Accelerators program. If one counts $3.25 billion as the five-year Engines authorization, then the program has received only about 6% of its authorization so far, or 15% if it receives the FY 2024 request level.

- Distressed Area Recompete Pilot Program: This EDA program—designed to deliver grants to distressed communities to connect workers to good jobs—is a relative bright spot funding-wise. Authorized at $1 billion over the FY 2022 to FY 2026 period, the program received its full $200 million in FY 2023 and has secured the same amount in the FY 2024 request. With that said, the program could still be under threat if the debt ceiling face-off leads to spending cuts.

Table 3: Placed-based innovation authorized in CHIPS and Science Act

| Program | What It Does | CHIPS and Science Authorizations | Appropriation So Far | FY24 OMB Budget | Percent of Authorization Funded To Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDA Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs | Planning grants to be awarded to create regional technology hubs focusing on technology development, job creation, and innovation capacity across the U.S. | $10 billion over five years | $500 million | $48.5 million discretionary; $4 billion mandatory | 5% |

| EDA Recompete Pilot Program | Investments in communications with large prime age (25-54) employment gaps | $1 billion over five years | $200 million | $200 million | 20% |

| NSF Regional Innovation Engines | Up to 10 years of funding for each Engine (total ~$160 million per) to build a regional ecosystem that conducts translatable use-inspired research and workforce development | $3.25 billion* over five years | $200 million | $300 million | 6% |

| NIST Manufacturing Extension Partnership | A network of centers in all 50 states and Puerto Rico to help small and medium-sized manufacturers compete | $575 million | $188 million | $277 million | 68% |

| NIST Manufacturing USA | Program office for nationwide network of public-private manufacturing innovation institutes | $201 million | $51 million | $98 million | 53% |

| Totals (including MEP and M-USA FY23 authorizations) | $15 billion | $1.1 billion | 8% | ||

| * The NSF Regional Innovation Engines is assumed to have received 50% of a $6.5 billion CHIPS and Science Act provision that also authorized the Translation Accelerators program | |||||

Besides these new CHIPS programs, two established mainstays of place-based development in the manufacturing domain are also facing funding challenges.

- NIST Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership: This program was slated for sizable boosts, with a $275 million authorization in FY 2023 and $300 million in FY 2024. The FY 2023 appropriation ended up $87 million short, while the FY 2024 request seeks a degree of catch-up, to within $23 million of the authorization. The request would support the National Supply Chain Optimization and Intelligence Network, to be established in FY 2023, and expand workforce up-skilling, apprenticeships, and partnerships with historically Black colleges and universities, minority-serving institutions, and community colleges.

- NIST Manufacturing USA: This program received $51 million in FY 2023 (about half of what was authorized), while the FY 2024 request again gets closer to the authorization, at $98 million. In FY 2024, NIST seeks to establish Manufacturing USA test beds, support a new NIST-sponsored institute to be completed in FY 2023, and further assist small manufacturers with prototyping and scaling of new technologies. As with all FY 2024 initiatives, outcomes depend partly on how tough the debt ceiling deal is for annual appropriations.

Overall, the current and likely future funding shortfalls facing many of the nation’s authorized place-based investments appear set to diminish the reach of these programs.

Should funding for critical technology areas be mandatory?

The CHIPS and Science Act establishes a compelling vision for U.S. innovation and place-based industrial policy, but that vision is already being hampered by tight funding. And now, the looming debt ceiling crisis is only going to make the situation worse.

Nor are there any silver bullets to resolve the situation. Somehow, Congress has to keep in sight the long-term vision for U.S. economic and military security, and find the political will to make the near-term financial commitments necessary for U.S. innovators, firms, and regions.

But it’s not just up to Congress. As we’ve seen, the White House budget also contains sizable funding shortfalls for research agencies. Federal agencies and the Office of Management and Budget will be formulating their FY 2025 budgets this summer in preparation for release next year. As they do so, they should prioritize long-term U.S. competitiveness across strategic technology areas and geographies more so than they have to date.

Lastly, while the mandatory spending proposal mentioned above for the Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs program may not get anywhere this year, mandatory funding as a mechanism for science and innovation investment is not a bad idea in principle. Nor is this the first time policymakers have pitched such an idea: The Obama administration attempted to make aggressive use of mandatory spending to supplement its base research and development requests, and congressional leaders have also floated the idea in recent years. Given the long-term nature of science and innovation, sustained and predictable support would be a boon, and a mandatory funding stream could provide much-needed stability.

Given all this, the moment may be approaching try again to leverage mandatory funding of innovation programs. With caps on discretionary spending on the horizon but bipartisan support for the CHIPS technology agenda still in place, the time to consider a mandatory funding measure may have arrived. Such a measure—structured by, say, a “Critical Technology and National Security Fund”—would go a long way toward ensuring more sustained, stable support for critical technologies in economic and military security. This is exactly the kind of support that CHIPS provides for the semiconductor industry, which is far from the only advanced technology sector subject to global competition.

In short, as we enter the summer months and face down a looming budget crisis, Congress should do for the “science” part of its watershed bill what it did with the “chips” part. Leaders in Washington must move now to ensure that we can deliver on the commitments set forth in the CHIPS and Science Act—all of them.

CHIPS and Science Funding Update: FY 2023 Omnibus, FY 2024 Budget Both Short by Billions

See PDF for more charts.

When Congress adopted the CHIPS and Science Act (P.L. 117-167) in 2022 on bipartisan votes, it was motivated by several concerns and policy goals. A major overarching theme is the global competition for technology and prominence in the knowledge economy, and the place of the United States in it. More broadly, Congress also sought to improve the ability of federal agencies to invest in R&D to create solutions for national challenges. To that end, the Act took a broad array of policy steps well beyond semiconductors: providing strategic focus for the federal technology enterprise, creating programs to invest in U.S. workers and regions, expanding the funding toolkit, and authorizing sizable boosts for R&D across the spectrum.

But neither the FY 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act nor the Biden Administration’s FY 2024 budget request have managed to keep up with the agency funding commitments established in the act. FY 2023 omnibus funding was nearly $3 billion short of the authorized targets for the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology. The FY 2024 request for these agencies is over $5 billion short (see graph below).

This report provides a detailed breakdown of accounts and programs for these agencies and compares current funding levels against those authorized by CHIPS and Science. The report is intended to serve as a reference and resource for policymakers and advocates as the FY 2024 appropriations cycle unwinds.

Based on agency and legislative data and the FY 2024 budget. | Federation of American Scientists

CHIPS and Science Background

As mentioned above and covered more fully below, CHIPS and Science took manifold steps to strengthen the U.S. science and technology enterprise. A conceptual throughline in the Act is the establishment of key technology focus areas and societal challenges defined in Section 10387, shown in the table below. While not the only priorities for the federal R&D enterprise, these focus areas provide a framework to guide certain investments, particularly those by the new NSF technology directorate.

These key technology areas are also relevant for long-term strategy development by the Office of Science and Technology Policy and the National Science and Technology Council, as directed by CHIPS and Science. Several of the technology areas also appear on the Defense Department’s Critical Technologies list.

| >> Key Technology Focus Areas >> | |

| AI, machine learning, autonomy* | Advanced communications and immersive technologies* |

| Advanced computing, software, semiconductors* | Biotechnology* |

| Quantum information science* | Data storage and management, distributed ledger, cybersecurity* |

| Robotics, automation, advanced manufacturing | Advanced energy technology, storage, industrial efficiency* |

| Natural / anthropogenic disaster prevention / mitigation | Advanced materials science* |

| * Also related to OUSD(R&E)-identified Defense Critical Technology Area |

|

| >> Societal / National / Geostrategic Challenges >> | |

| U.S. national security | Climate change and sustainability |

| Manufacturing and industrial productivity | Inequitable access to education, opportunity, services |

| Workforce development and skills gaps | |

| Adapted from H.R. 4346, Sec. 10387 | |

While much of the focus has been on semiconductors, the activities covered in this report constitute the bulk of the “and Science” portion of CHIPS and Science. While a full index of all provisions is not the goal here, it’s worth remembering the sheer variety of activities authorized in CHIPS and Science, which cut across a few broad areas including:

- Fundamental science and curiosity-driven research funded by science agencies at federal labs, universities, and companies. CHIPS and Science covered multiple disciplines but has a particular emphasis on the physical sciences, math and computer science, and engineering. Several of these disciplines have fallen dramatically within the federal portfolio in recent decades.

- Use-inspired research, translation, and production. Elements of CHIPS and Science sought to expand the ability of federal agencies to make strategic investments in emerging technologies, move new advances through the innovation chain, and work with external partners to enable the manufacture of new technologies and strengthen supply chains.

- Regional innovation. A major element of the above is emphasis on expanding the geographic footprint of federal investment, most notably through the new Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs program. The program received $500 million out of an authorized $10 billion in the FY 2023 omnibus.

- STEM education and workforce. The Act expands or creates numerous programs to foster STEM skills, opportunity and experience among students and young researchers, including through entrepreneurial fellowships, student and educator support, and apprenticeships and worker upskilling initiatives.

- Research facilities and instrumentation at national labs and universities across the country, including modernization of aging infrastructure, construction of cutting-edge user facilities, and grants for mid-scale research infrastructure projects.

Agency Fiscal Aggregates

In the aggregate, CHIPS authorized three research agencies – the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE Science), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) – to receive $22.4 billion in FY 2023. The final omnibus provided $19.6 billion in the aggregate, amounting to a $2.7 billion or 12% shortfall.

As seen in Table 1, the largest shortfall from the CHIPS authorization was NSF at $2 billion or 17% below the target. NIST’s appropriation actually surpassed the authorization by $103 million, but this figure includes $395 million in earmarks. Excluding earmarks, the NIST topline appropriation tallied to $1.3 billion, a $292 million or 19% shortfall below the authorization. Note the figures in Table 1 include $1.0 billion in supplemental appropriations for NSF – amounting to its entire year-over-year increase in FY 2023 – and $27 million in supplemental appropriations for NIST.

The White House requested an aggregate $21.7 billion for FY 2024: a $2.8 billion or 15% increase above FY 2023 omnibus levels (including earmarks and supplemental spending) but still $5.1 billion or 19% below the CHIPS and Science authorization in the aggregate. Again, NSF would be subject to the biggest miss below the authorized target.

Agency Breakdowns

National Science Foundation

NSF is at the core of the CHIPS and Science goals in manifold ways. It boasts a long-term track record of excellence in discovery science at U.S. universities and is the first or second federal funder of research in several tech-relevant science and engineering disciplines. It also seeks to boost the talent pipeline by engaging with underserved research institutions and student populations, supporting effective STEM education approaches, and providing fellowships and other opportunities to students and teachers.

CHIPS and Science also expanded NSF’s ability to drive technology, innovation, and advanced manufacturing, augmenting existing innovation programs like the Engineering Research Centers and the Convergence Accelerators with new activities like the Regional Innovation Engines.

As seen in Table 2, the FY 2023 appropriation for NSF – including $1.0 billion in supplemental spending – fell $2.0 billion or 17% below the CHIPS and Science target, while the FY 2024 request is $4.3 billion or 28% below the FY 2024 target. Additional details and comparisons between appropriations, authorizations, and the request follow.

Research & Related Activities (R&RA). R&RA is the primary research account for NSF, supporting grants, centers, instrumentation, data collection, and other activities across seven directorates including the new Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships (TIP) directorate. R&RA can likely absorb substantial additional funding: the agency must routinely leave thousands of high-scoring grant proposals on the table for lack of funding. For instance, in FY 2020 alone, NSF had to leave over 4,000 proposals ranked “Very Good” or better unfunded. These amounted to $3.9 billion in total unfulfilled award funding. A brief look at specific line items within the R&RA account are below.

- Core Research Directorates. Most R&RA funding is channeled through the six research directorates focusing on biology, computing and information science, engineering, geoscience, math and computer science, and social science, as well as integrated and international programs. These directorates play a foundational role in fostering U.S. scientific disciplines, including several that are germane to CHIPS technology priorities. Congress typically – and wisely – does not provide appropriations by individual directorate, and instead appropriates a lump sum for R&RA that is then allocated by the agency, though appropriators do sometimes specify funding amounts for line items or research topics. Accordingly, most of the R&RA authorization in CHIPS and Science is unspecified with two exceptions: $55 million for mid-scale research infrastructure projects, which was fully funded in the FY 2023 omnibus; and the TIP Directorate, covered below. Excluding these elements, core R&RA funding received $6.9 billion in the FY 2023 omnibus, about $591 million or 8% below the authorized level. Core R&RA funding in the request – again excluding TIP and mid-scale infrastructure – is $846 million or 10% below the authorized level.

- Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP). (FY 2023 funding: $880 million, $620 million below authorization; FY 2024 OMB request: $1.2 billion, $2.2 billion below authorization). NSF TIP was formally established in the CHIPS and Science Act to support translational, use-inspired, and solutions-oriented R&D and to deploy novel funding modes to accelerate innovation. Authorizers set a TIP funding target of $1.5 billion in FY 2023 and $3.4 billion in FY 2024, representing by far the most ambitious appropriations targets in the bill. FY 2023 funded was allocated by the agency rather than Congress, which should continue its practice of lump-sum appropriations for R&RA mentioned above. The FY 2024 TIP request is billions short of the authorized level yet also seeks the largest increase of any NSF directorate. Within TIP, CHIPS authorized $6.5 billion over five years combined for regional innovation engines and innovation translation accelerators and $125 million over five years for NSF entrepreneurial fellows, along with test beds, scholarships, R&D, and other activities.

STEM Education. The Directorate for STEM Education houses NSF activities across K-12, tertiary education, learning in informal settings, and outreach to underserved communities. CHIPS and Science authorized multiple individual programs including:

- Graduate Research Fellowship Program (FY 2023 funding: $322 million, $94 million below authorization; FY 2024 request: $380 million, $74 million below authorization). The program provides an excellent opportunity for students pursuing STEM careers while seeking to broaden participation.

- Robert Noyce Teacher Fellowship Program (FY 2023 funding: $69 million, $5 million below authorization; FY 2024 OMB request: $77 million, $3 million below authorization). The fellowship provides stipends, scholarships, and programmatic support to prepare and recruit highly skilled STEM professionals to become K-12 teachers in high-need districts. The CHIPS and Science Act aims to increase outreach to historically Black colleges and universities, minority institutions, higher education programs that serve veterans and rural communities, labor organizations, and emerging research institutions.

- CyberCorps (FY 2023 funding: $86 million, $16 million above authorization; FY 2024 OMB request: $74 million, $2 million above authorization). One of the few programs for which funding topped CHIPS authorized levels, CyberCorps aims to address the shortage of cybersecurity educators and researchers and augment the federal workforce by funding scholarships in exchange for a period of federal service.

- Centers for Transformative Education Research and Translation: This new program is intended to pursue multidisciplinary R&D into education innovations. under-resourced schools and learners in low-resource or underachieving local educational agencies in urban and rural communities.

Cross-Cutting Investments in Key Technology Focus Areas. Several NSF investments are related to the key technology areas and societal challenges prioritized in CHIPS section 10387 mentioned above. A breakout of some of these is below, taken from the NSF budget justification. Funding for these research activities is spread across all NSF directorates.

Department of Energy Office of Science

The Office of Science (SC) is the largest funder of the physical sciences including chemistry, physics, and materials, all of which contribute to the technology priorities in CHIPS and Science. In addition to funding Nobel prizewinning basic research and large-scale science infrastructure, the Office also funds workforce development, use-inspired research, and user facilities that provide tools for tens of thousands of users each year, including hundreds of small and large businesses that use these services to drive breakthroughs. More than two thirds of SC-funded R&D is performed at national labs. SC also supports workforce development and educational activities for students and faculty to expand skills and experience.

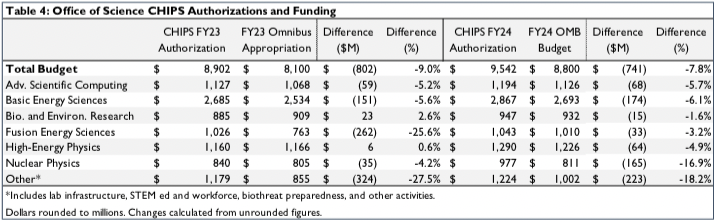

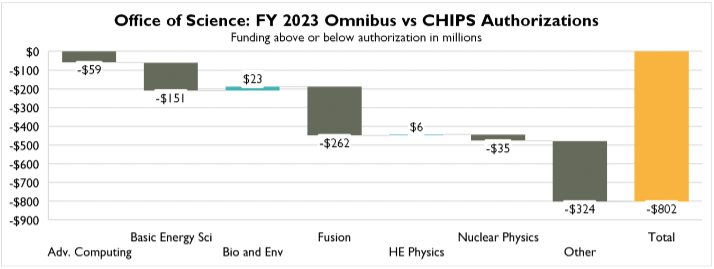

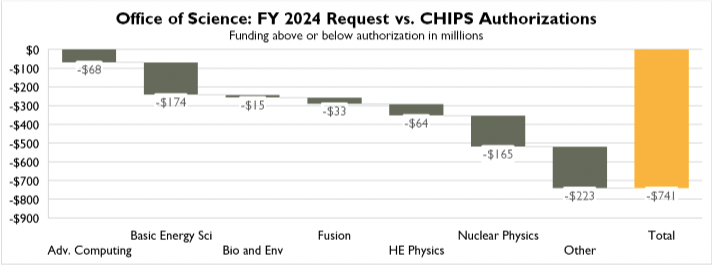

As seen in Table 4, the FY 2023 omnibus topline for SC was $802 million or 9% below the authorized amount, while the FY 2024 OMB request was $741 million or 8% below the FY 2024 authorization – and indeed even fell below the FY 2023 authorization, similar to NSF’s request. Most programs would see only moderate funding increases, with fusion clearly prioritized.

Funding above or below authorizations in millions

Funding above or below authorizations in millions

- Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) funds research in AI, computational science, mathematics, and networking. Among CHIPS and Science priorities, ASCR will begin to establish a dedicated Quantum Network along with other research, testbeds, and applications in FY 2024. CHIPS authorized quantum network infrastructure at $100 million in FY 2024 and quantum hardware and research cloud access at $31.5 million in FY 2024. CHIPS and Science also authorized Computational Sciences Graduate Fellowships at $16.5 million in FY 2024.

- Basic Energy Sciences (BES), the largest SC program, supports fundamental science disciplines with relevance for several CHIPS technology areas including materials, microelectronics, AI, and others, as well as extensive user facilities and novel initiatives like the Energy Earthshots. CHIPS and Science priorities included research and innovation hubs related to artificial photosynthesis ($100 million authorized in FY 2024) and energy storage ($120 million authorized in FY 2024). It also authorized $50 million per year for carbon materials and storage research in coal-rich U.S. regions. The FY 2024 request prioritizes budget growth in support of the program’s x-ray light sources and neutron sources.

- Biological and Environmental Research (BER) supports research in biological systems science including genomics and imaging, and in earth systems science and modeling. BER programs would generally see minimal changes from FY 2024, with a moderate funding boost for the Biopreparedness Research Virtual Environment to expand to include low dose radiation research, a CHIPS and Science priority area.

- Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) supports research into matter at high densities and temperatures to lay the groundwork for fusion as a future energy source. Following the breakthrough at the National Ignition Facility, the FY 2024 request ramps up commercial development and places industry partnerships – including technology roadmapping for a fusion pilot project as highlighted in CHIPS and Science – and establishment of four new fusion R&D centers among its fiscal priorities. It also seeks to largely sustain support for international ITER project.

- High Energy Physics (HEP) studies fundamental particles constituting matter and energy. The FY 2024 request prioritizes the Long Baseline Neutrino Facility/Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (LBNF/DUNE) while trimming research overall.

- Nuclear Physics (NP) conducts fundamental research to understand the properties of nuclear matter. The FY 2024 budget for NP is nearly flat, with a near-doubling of funding for Brookhaven’s Electron Ion Collider offsetting funding tightening elsewhere.

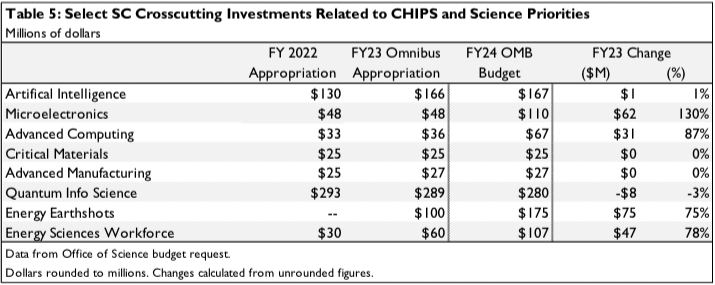

Cross-Cutting Investments in Key Technology Focus Areas. As with NSF, SC provides data on investments in crosscutting technology areas, some of which were prioritized in CHIPS and Science (Table 5). These investments involve multiple SC programs.

National Institute of Standards and Technology

While smaller than the other agencies covered here, NIST plays a critical role in the U.S. industrial ecosystem as the lead agency in measurement science and standards-setting, as well as funder of world-class physical science research and user facilities. NIST R&D activities cover several CHIPS And Science technology priorities including cybersecurity, advanced communications, AI, quantum science, and biotechnology. NIST also boasts a wide- ranging system of manufacturing extension centers in all 50 states and Puerto Rico, which help thousands of U.S. manufacturers grow and innovate every year.

As seen in Table 6, the NIST topline in the FY 2023 omnibus was $103 million above the CHIPS-authorized level. However, as noted in the above section, NIST received $395 million in Congressionally directed spending or earmarks in FY 2023, mainly for construction projects. Excluding earmarks, the NIST topline amounted to $1.3 billion, a $292 million or 19% shortfall below the authorization. The FY 2024 request is $20 million below the FY 2024 authorized level, with shortfalls in NIST labs programs and industrial technology.

Scientific and Technical Research Services (STRS) is the account for NIST’s national measurement and standards laboratories, which pursue a wide variety of CHIPS and Science-relevant activities in cybersecurity, AI, quantum information science, advanced communications, engineering biology, resilient infrastructure, and other realms. STRS also funds two user facilities, the NIST Center for Neutron Research and the Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology. In addition to FY 2024 investments in climate resilient infrastructure, research instrumentation, and other topics, large CHIPS and Science-relevant program increases include:

- Critical Technology Research ($20 million / 15% increase): In FY 2024, NIST lab programs will seek expanded investment in AI, quantum information science, biotechnology, and advanced communications. This will enable the establishment of AI technology testbeds, improve quantum metrology and support quantum technology development, promote rapid development and translation of biotechnologies and biomanufacturing processes, and advance measurement science and standards for next-generation communications.

- Cybersecurity and Privacy ($20 million / 21% increase): Funding will support research, standards development, and demonstrations of solutions through NIST’s National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence. These activities will touch on an array of critical areas including biometrics, cryptography, Internet of Things devices, and others. NIST will also continue to support cybersecurity workforce development. In addition to the above, NIST also requests $4 million for cybersecurity-relevant activities related to trustworthy supply chains.

Industrial Technology Services is the overarching account funding the Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) and the Manufacturing USA innovation network. As can be seen in Table 6, these programs collectively faced a much greater authorization shortfall than NIST lab programs in the FY 2023 omnibus, while the FY 2024 request goes to great lengths to increase their funding.

- Hollings MEP would use the FY 2024 boost to support the National Supply Chain Optimization and Intelligence Network, to be established in FY 2023, and to expand workforce upskilling, apprenticeships, and partnerships with historically black colleges, minority-serving institutions and community colleges.

- Manufacturing USA would establish testbeds throughout the network of manufacturing innovation institutes established by the Departments of Defense and Energy, support a new NIST-sponsored institute to be competed in FY 2023, and further assist small manufacturers with prototyping and scaling of new technologies.

Future Updates

Federation of American Scientists will create an update to this report as the relevant FY 2024 appropriations bills move through the Congressional process.

A First Look at CHIPS and Science Programs in the FY 2024 Request

On Thursday, President Biden kicked off the FY 2024 cycle with the latest budget request. This skinny version of the budget – full details of which will come on Monday – contained similar themes as prior budgets: a focus on clean energy and climate, manufacturing and supply chains, applied R&D, place-based innovation, and cancer research, among others.

But as the first budget before a divided Congress, the Administration’s plans face greater hurdles than in prior years. Pointing to a worsening long-term fiscal picture, the new House majority has proposed rolling discretionary spending back to FY 2022 levels which, if defense, veterans, and homeland security spending were left off the table, could include cuts of roughly 24% for other non-defense discretionary programs – the home for most federal science programs outside the Department of Defense.

Plus, proposals have already begun to emerge for long-term spending caps, which resulted in a cumulative R&D shortfall of over $200 billion the last time they were instituted under the Budget Control Act in 2011.

It may be a reflection of these difficult fiscal straits that the Administration somewhat scaled back its discretionary spending ambitions, requesting less than a 5% boost this time around versus a more than 7% boost last year. The budget continues to relatively favor nondefense increases (7.3%) versus defense (3.3%).

In spite of the scaled back request, there are still some large increases apparent thus far. A few of these are cited below, though additional details are TBD.

Overall Funding

Under the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act, three R&D agencies – the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy Office of Science (SC), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) – are authorized to receive up to $26.8 billion in FY 2024. This would represent a massive $7.2 billion or 37% jump from FY 2023 omnibus levels, which themselves ended up $3.2 billion short of the FY 2023 targets.

The Administration opts for a more moderate path in the request, providing $21.7 billion aggregate according to budget materials. This is still good for an 11% year-over-year increase, though $5.1 billion below the CHIPS and Science targets (see below).

Individually, NSF would receive a topline increase of 15% ($1.4 billion) and SC, 9% ($700 million). NIST would receive only a $5 million increase, though this comes with increases in research and, especially, technology programs (see below) mostly offset by a decline in construction funding – which saw substantial earmark spending in FY 2023.

Outside the discretionary budget, the Administration is also seeking $4 billion in mandatory expenditures for the Economic Development Administration’s Regional Technology and Innovation Hub Program, which was authorized at $10 billion in CHIPS and Science and received $500 million in the omnibus.

Agency Priorities

Much more agency detail will be available beginning Monday the 13th, but here’s a brief snapshot.

For NSF, the request includes $1.2 billion for the new Technology, Innovation and Partnerships Directorate including $300 million for the Regional Innovation Engines. The budget also includes $1.4 billion, a $198 million increase above the omnibus, for STEM education programs; $2 billion for R&D related to advanced industries; and $1.6 billion for climate R&D (several of these spending priorities likely overlap).

SC would receive a $680 million or 8% increase. This includes a billion-dollar investment in fusion; more will be revealed next week. Beyond SC, DOE proposes substantial research, development and demonstration (RD&D) investments to boost clean energy innovation, manufacturing, and the domestic supply chain.

NIST lab programs would see only a 4% increase according to the Department of Commerce budget table, while manufacturing programs would see a big jump: the Industrial Technology Services account would receive a $163 million increase above the omnibus to $375 million total, including $98 million for Manufacturing USA institutes, $60 million for domestic production of institute-developed technologies. The Manufacturing Extension Partnership would receive a $102 million increase to $277 million.

Congress May Miss CHIPS And Science Research Targets by Billions This December

Earlier this year Congress passed the CHIPS And Science Act: a once-in-a-generation piece of legislation to secure U.S. semiconductor manufacturing, enhance U.S. science investment, and foster the next generation of STEM talent.

But at the core of that legislation are aggressive spending targets for the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE SC), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). These targets tee all of these agencies up for sustained long-term growth, but Congress has to provide actual dollars to make it happen. Now, amid a looming funding deadline December 16, Congress is running the risk of falling substantially short of its own bipartisan aspirations.

To tally up the current shortfalls between current appropriations and aspirational CHIPS targets, FAS has produced a short report breaking down key programs and provisions by agency. Read below for a summary of major takeaways, or download now for the full report.

What is CHIPS and Science?

The CHIPS And Science Act has some of its original roots in calls almost three years ago to create a new technology directorate at NSF, ramp up federal science funding, and create regional tech hubs around the country. These investments are still at the final law’s core, along with policies to achieve additional goals like achieving energy security and fostering STEM talent. Collective program changes in the law offer the potential to boost domestic manufacturing, tackle supply-chain vulnerabilities, and power the workforce of the future in emerging industries.