The new Polish government caused a stir last weekend when deputy defense minister Tomasz Szatkowski said during an interview with Polsat News 2 that Poland was taking “concrete steps” to consider joining NATO’s so-called nuclear sharing program.

The program is a controversial arrangement where the United States makes nuclear weapons available for use by a handful of non-nuclear NATO countries.

The Polish Ministry of Defense quickly issued a denial saying Poland “is not engaged in any work aimed at joining NATO’s nuclear sharing program.”

Mr. Szatkowski’s statement, the Ministry said, “should be seen in the context of recent remarks made by serious Western think tanks, which point to deficits in NATO’s nuclear deterrent capability on its eastern flank.”

No Smoke Without A Fire

NATO has stated that it has no plans or intensions to deploy nuclear weapons further east in new NATO countries. Despite the Polish denial, however, Mr. Szatkowski’s statement didn’t come out of thin air but reflects deepening discussions within NATO about how the alliance should adjust its nuclear posture in Europe in response to Russia’s recent military operations and statements.

Only a few weeks ago senior U.K. officials said NATO was actively considering whether to reinstate nuclear escalation exercises in Europe to counter Russia. “Since the end of the Cold War, NATO has done conventional exercising and nuclear exercising, both, but not exercised the transition from one to the other,” said Sir Adam Thomson, the British permanent representative to NATO. That recommendation is now being looked at he said and added: “It is safe to say the UK does see merit in making sure we know how, as an Alliance, to transition up the escalatory ladder in order to strengthen our deterrence.” Defence Secretary Michael Fallon added: “We have to know how they fit together, nuclear and conventional.”

The British statements followed preliminary NATO discussion in June and more formal talks in October after warnings in February that Russia was adjusting its nuclear posture. Back then Fallon explained there were three concerns: “first that they (the Russians) may have lowered the threshold for use of nuclear. Secondly, they seem to be integrating nuclear with conventional forces in a rather threatening way and [third]… at a time of fiscal pressure they are keeping up their expenditure on modernizing their nuclear forces.”

While the diplomats in public are talking about considerations, the military has already begun to adjust the nuclear posture. As part of Operation Atlantic Resolve, a new set of military operations and exercises recently created to provide “a unified response to revanchist Russia,” U.S. European Command (EUCOM) has quietly “forged a link between STRATCOM Bomber Assurance and Deterrence missions to NATO regional exercises” to beef up the NATO nuclear deterrence mission.

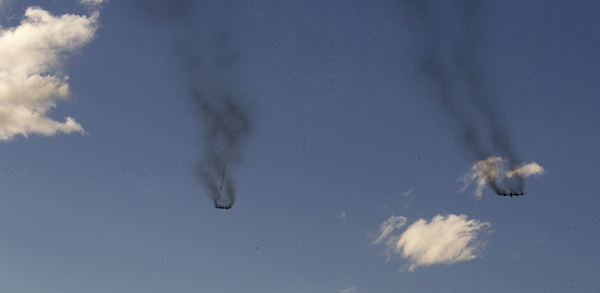

One of the first examples of this new “link” was Operation Polar Growl, a bomber exercise in April where four B-52 bombers took off from the United States and flew a non-stop strike mission over the North Pole and North Sea. The bombers did not carry nuclear weapons on the exercise but were equipped to carry a total of 80 air-launched cruise missiles with a total explosive power equivalent to 1,000 Hiroshima bombs – a subtle warning to Putin not seen since the Cold War.

Two B-52 bombers take off from Barksdale AFB on April 1, 2015 as part of Exercise Polar Growl over the North Pole and North Sea.

Conclusions and Recommendations

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, increased military operations, and explicit nuclear threats, General Philip Breedlove, the head of U.S. European Command (EUCOM) and NATO’s military commander, told the US Congress that the crisis in Europe is “not based on the nuclear piece. That’s not what worries me.” And U.S. Defense Secretary Ashton Carter declared that “In our response [to Russia], we will not rely on the Cold War play book.”

Yet NATO is starting to adjust its nuclear posture in Europe in ways that seem similar (but far from identical) to the Cold War play book: increased reliance on U.S. nuclear forces, adjustment of strategy and planning, more exercises and rotational deployments of nuclear-capable forces.

The statement by Polish deputy defense minister Tomasz Szatkowski is but the latest sign of that development.

It is unlikely that NATO will broaden its nuclear sharing arrangement to include Poland. It is already a member of NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group where it participates and votes on issues related to NATO nuclear planning. And Poland already participates in the so-called SNOWCAT program where it contributes non-nuclear capabilities in support of the nuclear mission in Europe but is not directly nuclear tasked. Last year we saw Polish F-16s participate in NATO’s nuclear strike exercise for the first time in SNOWCAT role.

Taking this one step further for Poland to become part of the nuclear sharing arrangement similar to Belgium, Germany, Holland, Italy and Turkey that store US nuclear weapons on their territory, equip their national jets and train their national pilots with the capability to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons, would be an unnecessary and counterproductive overreaction to Putin’s unacceptable military escapades.

It would worsen, not improve, security in Europe, waste resources that are needed for conventional forces, and deepen the political and military crisis between NATO and Russia. It would be akin to Russia deciding to provide nuclear weapons for Belarusian fighter jets.

Moreover, while the existing nuclear sharing arrangements in NATO (all of which are bi-lateral arrangements between the United States and the host country) date back from before the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) came into effect and therefore was accepted by the treaty regime, broadening the arrangement to Poland (or anyone else) would be a new situation and therefore a violation of the NPT.

Yet some NATO officials, former government officials, and academics, have been trying for years to persuade NATO to increase – or at least not reduce – reliance on nuclear weapons in Europe. For them, Putin’s actions represent a refreshing opportunity to get what they wanted anyway. The NATO Summit in Warsaw next summer is expected to decide on how far to go.

NATO should reject attempts to reinvigorate the nuclear posture in Europe and instead focus its military planning where it matters: enhancing conventional capabilities (to the extent it doesn’t further increase Russian reliance on nuclear weapons) with U.S. nuclear forces (and to a lesser extent those of Britain and France) providing an assured nuclear retaliatory capability in the background.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.