There are not many public pictures showing the U.S. ballistic missile submarine visits to South Korea. This one apparently shows the USS John Marshall (SSBN-611) in Chinhae in 1979. The submarine carried 16 Polaris A3 missiles with a total of 48 200-kt warheads.

.

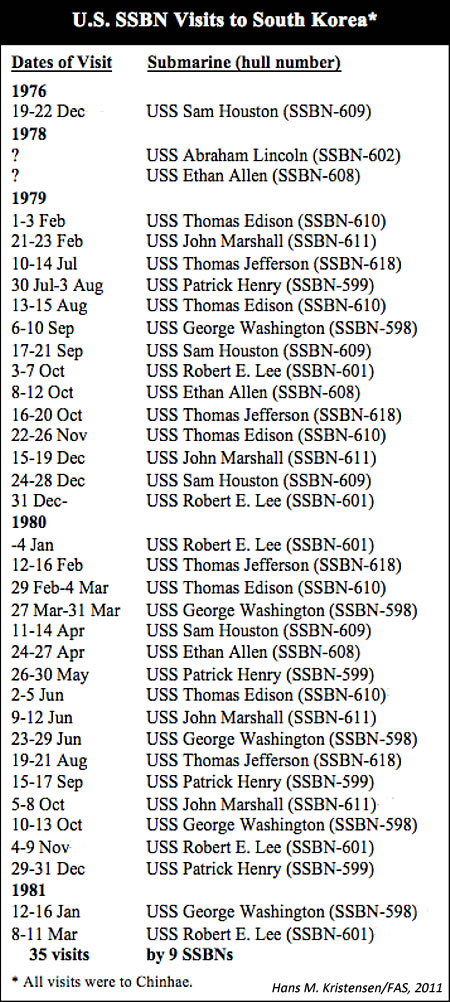

Back in the late-1970s, U.S. nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines suddenly started conducting port visits to South Korea. For a few years the boomers arrived at a steady rate, almost every month, sometimes 2-3 visits per month. Then, in 1981, the visits stopped and the boomers haven’t been back since.

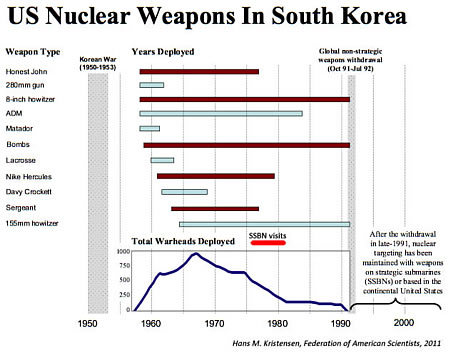

At the time the visits began, the United States also had several hundred nuclear weapons deployed on land in South Korea, but the submarine visits apparently were needed to further demonstrate that the United States was prepared to defend the south against an attack from the north.

After North Korea’s nuclear tests in 2006 and 2009, shelling of South Korean territory and the sinking of one of its warships, there have been reports recently that an increasing number of South Koreans want the United States to deploy nuclear weapons in South Korea again, after the last such weapons were withdrawn in 1991. They think it is necessary to deter North Korea.

Some analysts have even suggested that the United States should develop an improved nuclear earth penetrator to better threaten North Korean deeply buried targets, an idea that was previously proposed the Bush administration but rejected by Congress.

Boomers in Chinhae

The SSBN visits to South Korea are unique; the United States normally does not send SSBNs into foreign ports. But there are exceptions. In 1963, the USS Sam Houston (SSBN-609) sailed into Izmir in Turkey on a mission to assure the Turkish government that the United States still had the nuclear capability to defend Turkey even after Jupiter missiles were withdrawn from bases in Turkey following the Cuban missile crisis. The Izmir visit was a one-time event, however, and no SSBN visited foreign ports for the next 12 years.

|

| Between December 1976 and March 1981, nine U.S. ballistic missile submarines conducted 35 port visits to South Korea |

Then, on December 19, 1976, the USS Sam Houston suddenly arrived in Chinhae, South Korea. The ship was under order to “surface in Korea for 3 days to ‘rattle the saber,” according to a former crew member. This was the first foreign port visit of a U.S. SSBN in the Pacific.

Two visits followed in 1978 but in 1979 the operations expanded with 14 visits conducted by eight SSBNs. In October that year, three SSBNs made three visits for a combined presence of 15 days.

The following year, in 1980, the number of visits expanded to 15, in June with three visits for a combined 17 days in port. In 1981, coinciding with the phase-out of the Polaris SLBM, the visits dropped to only two.

The Political Context

The 35 port visits conducted by nine SSBNs to Chinhae were a powerful message to South Korea and its potential adversaries about the U.S. nuclear capabilities in the area. But exactly what the reasons for the visits were remain unclear.

The visits took place in a complex political situation. South Korea had started a program to develop nuclear weapons technology, President Carter wanted to withdraw U.S. nuclear weapons from South Korea, and North Korea was building up its military forces backed by China and the Soviet Union.

Ironically, South Korea had started a nuclear weapons technology program in 1974 not because of doubts about the U.S. nuclear umbrella per ce, but because, according to the CIA, of doubts about the reliability of the overall U.S. security commitment. The program reportedly was terminated in 1976 after U.S. and French pressure. [See here for an insightful analysis]

At the same time, newly elected president Jimmy Carter wanted to withdraw U.S. nuclear weapons from bases in South Korea. At the time the SSBN visits began, the U.S. had approximately 500 ground-launched nuclear weapons at bases in South Korea – roughly the same number of warheads as onboard the missiles of the nine visiting SSBNs. [For a brief history of U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons in South Korea, go here]. In the end, Carter’s withdrawal didn’t happen but the land-based weapons were significantly reduced (see below).

|

| During the time of the SSBN visits, the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in South Korea was reduced from roughly 500 to 150. The last were withdrawn in 1991. |

.

The SSBN visits might also have been designed to remind China about the U.S. military presence in the region, despite its defeat in Vietnam. The end of the SSBN visits to South Korea in 1981 and the phase-out of the Polaris SSBNs fleet in the Pacific coincided with China’s removal from the U.S. strategic war plan as part of the Reagan administration’s efforts to recruit China as a partner against the Soviet Union. (China was later reinstated in the war plan in 1997 by the Clinton administration.)

In September 1982, the first new Ohio-class SSBN deployed on its first patrol in the Pacific and over the next five years it was followed by seven other boats, each loaded with 24 longer-range and more accurate Trident I C-4 missiles. (All have since been upgraded to the even more capable Trident II D-5 missile). None of the Trident SSBNs have ever visited South Korea, even after the withdrawal of the last land-based nuclear weapons from the country in 1991.

Implications

The SSBN visits to South Korea are a curious but little noticed footnote in the Cold War history. More research is needed to better describe exactly why they happened, but the visits seemed intended to signal assurance to South Korea and deterrence to its adversaries.

As such the visits have potential implications for today. North Korea has since crossed the nuclear threshold, support seems to be growing in South Korea for returning U.S. nuclear weapons to the peninsula, and some argue that better nuclear capabilities are needed to deter Pyongyang.

But the visits are a reminder of the already considerable nuclear capabilities in the region that could be used to signal. Nuclear-capable bombers routinely forward deploy to Guam, and the eight SSBNs patrolling in the Pacific could surface again and visit South Korea if necessary.

|

| Nearly 30,000 U.S. troops in South Korea, large-scale conventional exercises such as the three-carrier battlegroup Valiant Shield (image) and the half-a-million-man Ulchi Freedom Guardian, as well as forward operations of nuclear-capable forces in the region provide a powerful deterrent. |

.

The question is whether it is necessary. The nuclear capabilities the United States operates in the Pacific region today are far more capable than in the 1970s, and the combined conventional forces of South Korea and the United States enjoy a significant advantage over North Korea’s aging conventional forces. To the extent that anything can, these forces should be sufficient to deter large-scale North Korean attacks against the south.

Indeed, Pyongyang’s obsession with the U.S. nuclear capabilities – even its misperception that Washington still deploys nuclear weapons in South Korea – strongly suggests that the current nuclear umbrella has Pyongyang’s full attention and that nuclear redeployment or nuclear bunker busters are not needed. After all, the objective is to move forward toward a denuclearization of the Korean peninsula, not return to the past.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

With tensions and aggressive rhetoric on the rise, the next administration needs to prioritize and reaffirm the necessity of regular communication with China on military and nuclear weapons issues to reduce the risk of misunderstandings.

Congress should ensure that no amendments dictating the size of the ICBM force are included in future NDAAs.

In early November 2024, the United States released a report describing the fourth revision to its nuclear employment strategy since the end of the Cold War and the third since 2013.

Life-extending the existing Minuteman III missiles is the best way to field an ICBM force without sacrificing funding for other priorities.