Russian Strategic Submarine Patrols Rebound

|

| Russian SSBN patrols tripled from 2007 to 2008. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

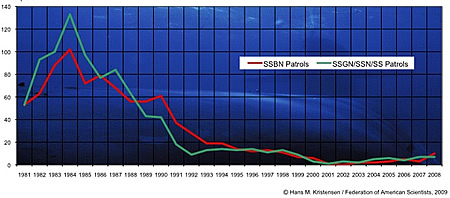

Russia sent more nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines on patrol in 2008 than in any other year since 1998, according to information obtained by Federation of American Scientists from U.S. naval intelligence.

The information shows that Russian missile submarine conducted ten patrols in 2008, compared with three in 2007 and five in 2006. In 2002, no patrols were conducted at all.

Return of Continuous Russian SSBN Patrols?

For the past ten years, Russian remaining 11 SSBNs have not maintained continuous patrols, but instead carried out occasional patrols for training purposes. Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov said in on September 11, 2006, that five SSBNs were on patrol at that time. But since that number matched the total number of patrols conducted that year, it revealed a cluster of patrols rather than a continuous at-sea presence.

The United States, France and Britain, in contrast, continuously have at least one SSBN on patrol. In the case of the United States, two-thirds of its 14 SSBNs are at sea at any given time, of which four are on alert.

.

The ten Russian patrols in 2008 raise the question whether Russia has now resumed continuous SSBN patrols. Neither the duration nor the dates of Russian SSBN patrols are known, but if they east last more than 36 days and do not overlap, then Russia could have a continuous at-sea deterrent. If the patrols cluster like in 2006, then the posture might still be sporadic.

The Voyage of Ryazan

Although not specified in the information obtained from U.S. naval intelligence, one of the Russian patrols probably was the 30-days under-ice voyage of the Delta III-class submarine Ryazan from the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula in the Barents Sea to the Pacific Fleet on the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Pacific.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| One of the 10 SSBN patrols probably involved the transfer of a Delta III SSBN from the Northern Fleet to the Pacific Fleet. |

.

The voyage occurred shortly after Ryazan completed a successful test launch of a ballistic missile – probably an SS-N-18 – from the Barents Sea on August 1, 2008. The missile type was not announced, which is unusual, but its payload flew across Northern Russia and impacted in the Kura test range on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

At end the of August, Ryazan departed the Northern Fleet and sailed submerged along Russia’s ice covered northern coast through the Bering Strait before it headed south to the ballistic missile submarine base in Vladivostok, where it arrived on September 30.

Arms Control Implications

It would be ironic – now that the Obama administration has proposed reductions in strategic nuclear forces and Kremlin seems to respond favorably – if Russian SSBNs returned to the Cold War practice of continuous deterrent patrols.

SSBNs continuously roaming the oceans are one of the last symbols of the Cold War when long-range nuclear missiles were hidden in the deep to survive a massive first strike. United States SSBNs continue a patrol rate comparable to that of the 1980s, France and Britain try to keep one or two at sea at any time – two apparently collided last month, and China and India are trying to build SSBNs fleets too.

Many still see SSBNs as purely retaliatory weapons passively hiding in the oceans. But as U.S. and Russian nuclear forces are reduced further and China and India join the SSBS club, forward deployed submerged nuclear weapons could become some of the most problematic challenges for nuclear arms control.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.