Spanish-language vaccine news stories hosting malware disseminated via URL shorteners

Key Highlights

- Compared to our September report, this update discovered a much larger Spanish-language news network of COVID-19 vaccine stories with embedded malware files for all major vaccines. Now, through link-shortening services such as bit.ly, a third-party has disseminated vaccine-related malware across Latin America.

- The news of a possible adverse reaction to the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine triggered a wave of social media activity. The volume of shares, mentions, and tweets formed an ideal entry-point for malicious actors to potentially distribute malware to hundreds of thousands of unwitting readers. Embedded malware may provide opportunities for malicious actors to manipulate web traffic in order to amplify narratives that cast doubt on the efficacy of particular vaccines. These efforts have since been operationalized in at least five Latin American countries to undermine trust in the Oxford-AstraZeneca, Moderna, and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines.

- An initial analysis of 88,555 Spanish-language tweets found Russia’s mundo.sputniknews.com to be the epicenter of these malware files, with eight additional infected files detected since our previous analysis. A second set of scans identified more instances of malware on the domain compared to the initial 17 scans in a previous report.

- We discovered evidence of link-shortening services being used to reroute links for stories on Latin American news outlets to malware-infected web pages. Link-shortening reduces the character count and makes it easier to click, but it also obscures the destination URL. 7,074 shortened bit.ly links were detected. This report found half of all randomly sampled bit.ly links are associated with infected sites.

Malware hosted within popular news stories about COVID-19 vaccine trials

On September 18, 2020, FAS released a report locating a network of malware files related to the COVID-19 vaccine development on the Spanish-language Sputnik News link mundo.sputniknews.com. The report uncovered 53 websites infected with malware that were spread throughout Twitter, after allegations of adverse reactions led to a pause in the Oxford-AstraZeneca (AZD1222) vaccine trial.

Whereas our first report collected 136,597 tweets and was only limited to the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, this update presents a collection of 500,166 tweets from Nov. 18 to Dec. 1 containing key terms “AstraZeneca”, “Sputnik V”, “Moderna”, and “Pfizer”. From that total, 88,555 tweets written in Spanish were analyzed for potential malware infections.

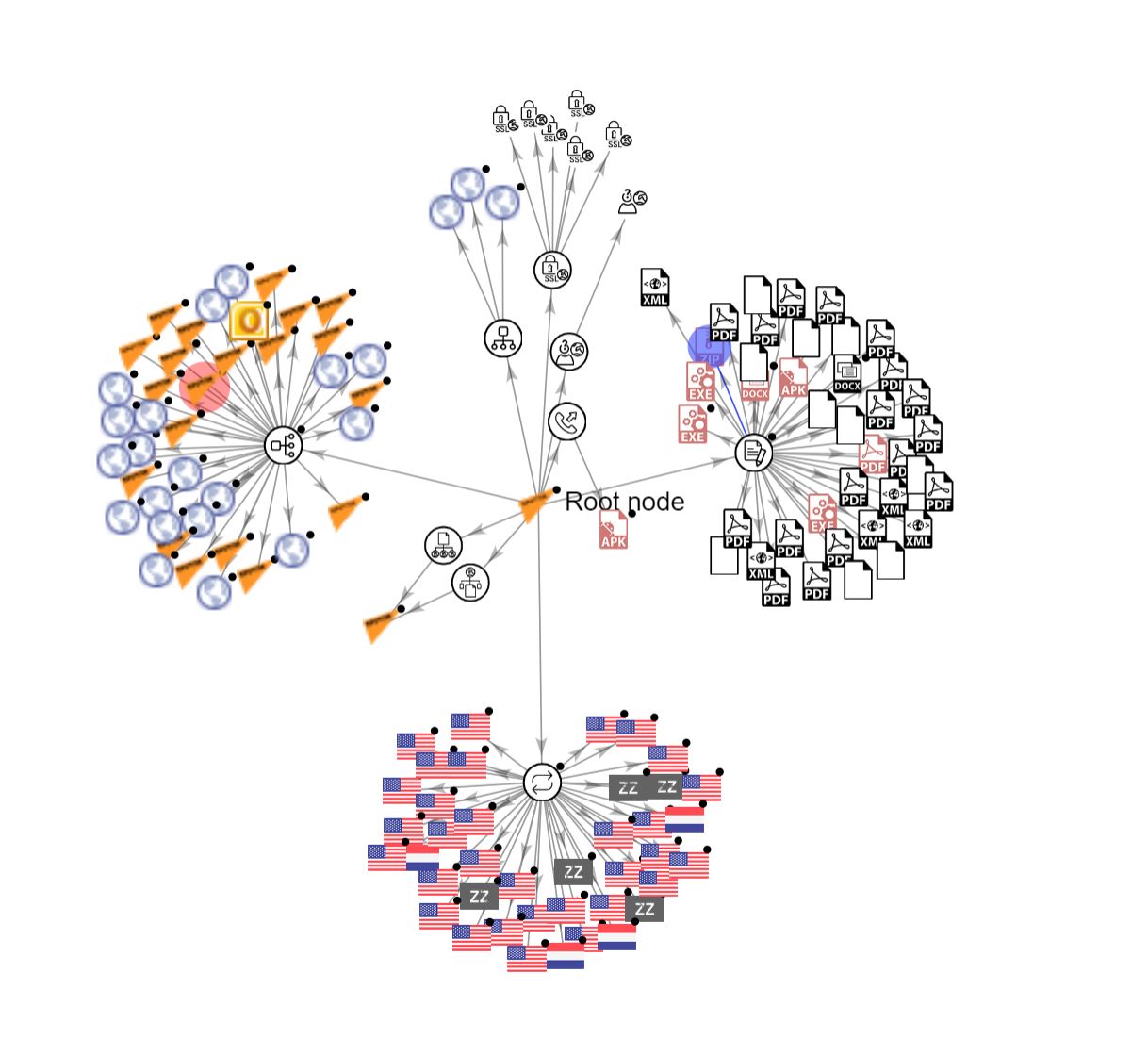

Our analysis determines that infections on the mundo.sputniknews.com domain are continuing. Eight separate files were discovered, with 52 unique scans detecting various malware — up from the 17 scans in the initial report (see Figure 1).

Many of the published stories contain information about possible complications or lean sceptically towards vaccine efficacy. The top translated story features the title “The detail that can complicate Moderna and Pfizer vaccines” (see Figure 2).

One possible explanation behind the use of malware is that perpetrators can identify and track an audience interested in the state of COVID-19 vaccines. From there, micro-targeting on the interested group could artificially tilt the conversation regarding certain vaccines favorably. Such a strategy works well with these sites, which are already promoting material questioning Western-based vaccines.

Additionally, within the Spanish-language Twitter ecosystem, 7,074 shortened bit.ly were discovered related to COVID-19 vaccines. The use of link shortening is a new discovery and a worrisome one. Not only does it enable additional messaging on Twitter by reducing URL characters, link-shortening can also obscure the final destination of the URL. The native Spanish-language news network suffering malware infection is structurally different from the Sputnik Mundo infection. Unlike the Sputnik Mundo domain, the bit.ly links routing to Latin American news outlets are doing so indirectly, first connecting to an IP that will refer the traffic to the news story URL but also hosts malware. This process has the potential to indirectly spread malware by clicking on bit.ly-linked embedded within Tweets.

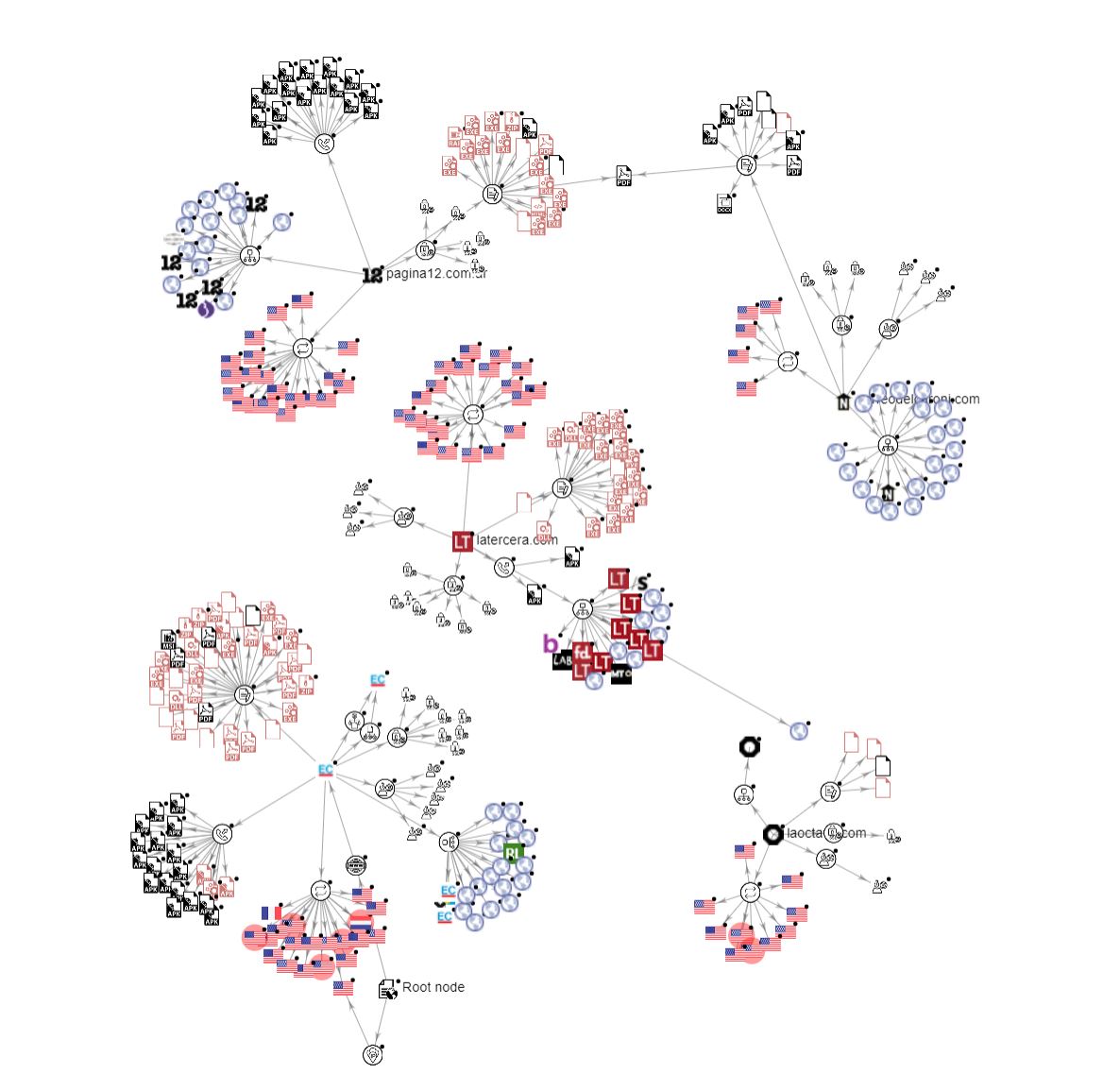

Of the bit.ly links shared more than 25 times, our analysis randomly selected ten. Half were infected and half were clean links. Infected domains included: an Argentine news site (www.pagina12.com.ar), an eastern Venezuelan newspaper (www.correodelcaroni.com), a Chilean news outlet (https://www.latercera.com), a Peruvian news outlet (https://Elcomercio.com), and a Mexican news outlet (https://www.laoctava.com).

The typology of malware within the infected network was diverse. Our results indicate 77 unique pieces of malware, including adware-based malware, malware that accesses Windows registry keys on both 32- and 64-bit PC systems, APK exploits, digital coin miners, worms, and others. Our analysis indicates that the malware is designed to monitor personal behavior on users’ devices.

The malware network is robust but not highly interconnected (see Figure 3).

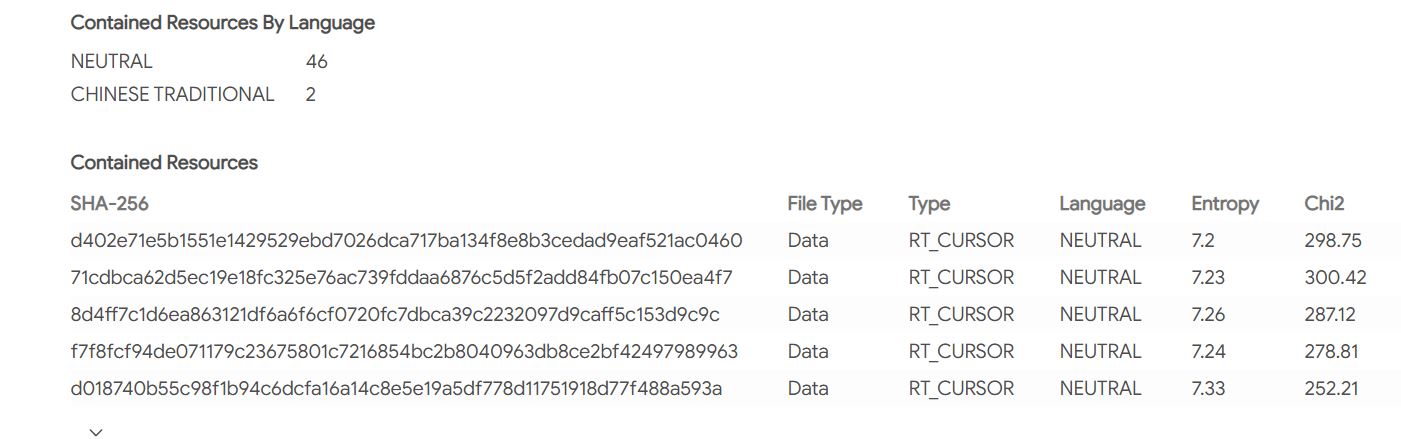

Examination of the malware contained within this network revealed interesting attribution information. While much of the specific malware (e.g. MD5 hash: 1aa1bb71c250ed857c20406fff0f802c, found on the Chilean news outlet https://www.latercera.com) has neutral encoding standards, two language resources in the file are registered as “Chinese Traditional” (see Figure 4).

As manipulation of language resources in coding is common, the presence of Chinese Traditional characters flagged in the malware’s code suggests the originators of the malware may be trying to confuse malware-detection software.

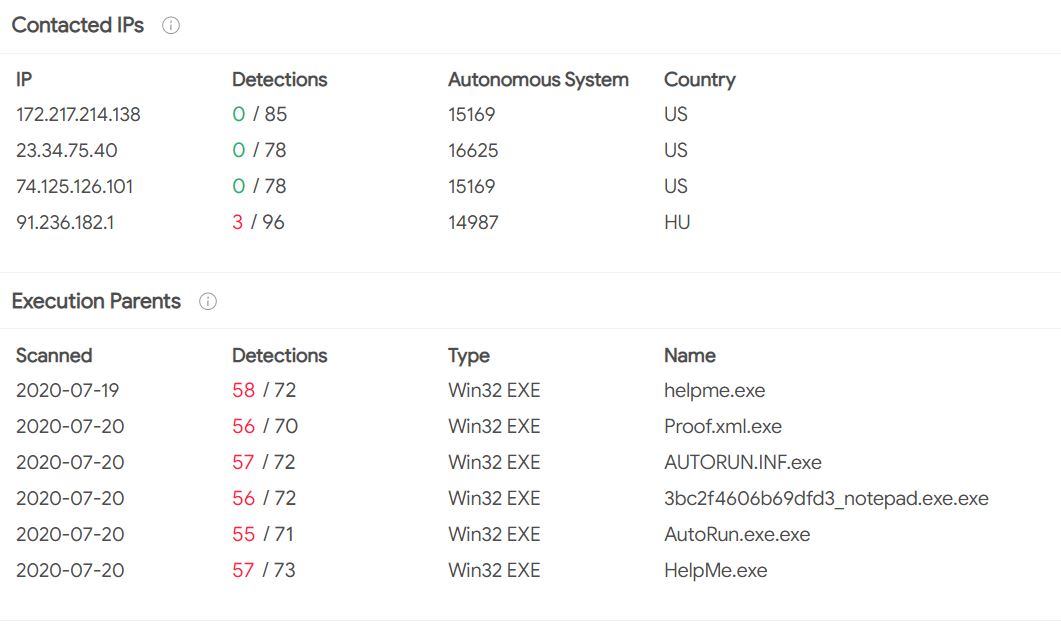

However, our analysis identified this malware’s IP address as located in Hungary, while its holding organization is in Amsterdam (see Figure 5). This IP address was also linked to the Undernet (https://www.undernet.org/), one of the largest Internet chat domains with over 17,444 users in 6,621 channels and a known source of malware origination. Again, this is but one malware on one Chilean news outlet pulled for closer inspection. Collectively, our findings demonstrate the networked production and distribution of malware in the COVID-19 vaccine conversation.

The malware network is large and presents a clear threat vector for the delivery of payload on vaccine stories. Vaccine malware-disinformation has spread beyond Russia’s Sputnik Mundo network and towards a series of other domains in Argentina, Venezuela, Chile, Peru, and Mexico. This is particularly alarming considering that aggressive conspiracy theories advanced by the Kremlin in Latin America have already tilted the region’s governments towards the use of the Sputnik V vaccine. Indeed, Russia is supplying Mexico with 32 million doses of Sputnik V. Venezuela and Argentina are set to purchase 10 million and 25 million doses respectively, while Peru is currently in negotiations to purchase the Sputnik V.

With a malware-curated audience, it will become significantly easier to pair the supply of Sputnik V with targeted information to support its use and delegitimize Western vaccines.

Considering that COVID-19 vaccine efforts are arguably the most important news topic on any given day, the spike in social media activity from the AstraZeneca COVID-19 clinical trial pause marked a key entry point for malware-disinformation. Since September, however, the network has largely permeated throughout Spanish-language Twitter — as did Sputnik V throughout Latin America.

With the explosion of reporting on the pandemic and vaccines, it is difficult to know what sites are safe and which are dangerous. This risk is magnified for less-savvy Internet users, who may not even consider the vulnerability of malware. Unfortunately, it is difficult to say the number of individuals that were infected from the malware discovered. Even one person clicking the wrong link could have a disastrous effect, as the malware siphons sensitive information from credit card numbers to confidential information appearing on a user’s screen.

Most worrisome is that the malware technique could create a library of users interested in vaccine stories who could be subsequently targeted. If used for micro-targeting, the library would become an effective audience to target with more vaccine misinformation.

Methodology

We performed a combination of social network analysis, anomalous behavior discovery and malware detection. We scanned 88,555 topic specific URLs run through an open source malware detection platform VirusTotal (www.virustotal.com).

For more about the FAS Disinformation Research Group and to see previous reports, visit the project page here.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.