The Obama administration has cut fewer nuclear weapons than any other post-Cold War administration.

It’s a funny thing: the administrations that talk the most about reducing nuclear weapons tend to reduce the least.

Analysis of the history of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile shows that the Obama administration so far has had the least effect on the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile of any of the post-Cold War presidencies.

In fact, in terms of warhead numbers, the Obama administration so far has cut the least warheads from the stockpile of any administration ever.

I have previously described how Republican presidents historically – at least in the post-Cold War era – have been the biggest nuclear disarmers, in terms of warheads retired from the Pentagon’s nuclear warhead stockpile.

Additional analysis of the stockpile numbers declassified and published by the Obama administration reveals some interesting and sometimes surprising facts.

What went wrong? The Obama administration has recently taken a beating for its nuclear modernization efforts, so what can President Obama do in his remaining two years in office to improve his nuclear legacy?

Effect on Warhead Numbers

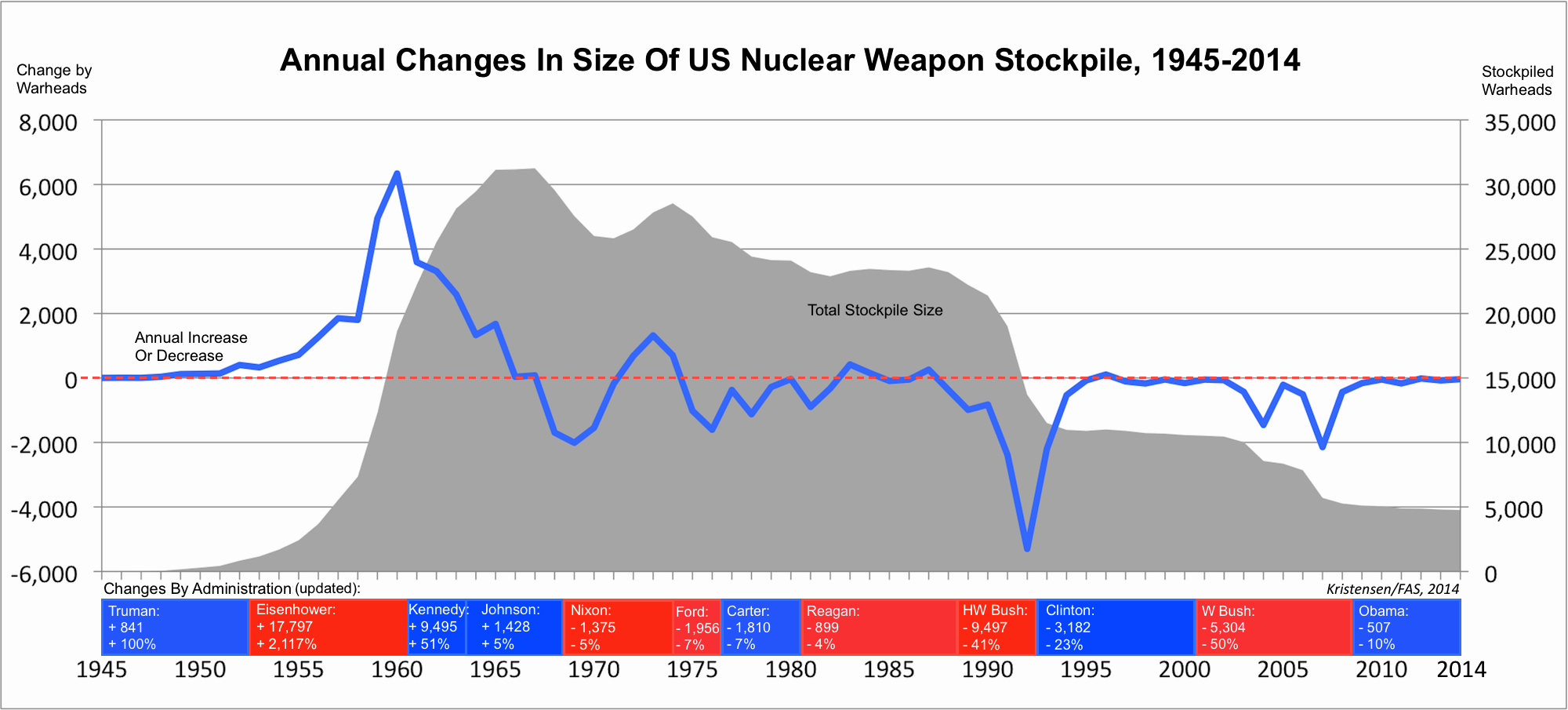

On the graph above I have plotted the stockpile changes over time in terms of the number of warheads that were added or withdrawn from the stockpile each year. Below the graph are shown the various administrations with the total number of warheads that each added or withdrew from the stockpile during its period in office.

The biggest increase in the stockpile occurred during the Eisenhower administration, which added a total of 17,797 warheads – an average of 2,225 warheads per year! Those were clearly crazy times; the all-time peak growth in one year was 1960, when 6,340 warheads were added to the stockpile! That same year, the United Sates produced a staggering 7,178 warheads, rolling them off the assembly line at an average rate of 20 new warheads every single day.

The Kennedy administration added another 9,495 warheads in the nearly three years before President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in October 1963. The Johnson administration initially continued increasing the stockpile and it was in 1967 that the stockpile reached its all-time high of 31,255 warheads. In its second term, however, the Johnson administration began reducing the stockpile – the first U.S. administration to do so – and ended up shrinking the stockpile by 1,428 warheads.

During the Nixon administration, the military started loading multiple warheads on ballistic missiles, but the stockpile declined for the first time due to retirement of large numbers of older warhead types. The successor, the Ford administration, reduced the stockpile and President Gerald Ford actually became the Cold War-period president who reduced the size of the stockpile the most: 1,956 warheads.

The Carter administration came in a close second Cold War disarmer with 1,810 warheads withdrawn from the stockpile.

The Reagan administration, which in its first term was seen by many as ramping up the Cold War, ended up shrinking the total stockpile by almost 900 warheads. But during three of its years in office, the administration actually increased the stockpile slightly, and the portion of those warheads that were deployed on strategic delivery vehicles increased as well.

As the first post-Cold War administration, the George H.W. Bush presidency initiated enormous nuclear weapons reductions and ended up shrinking the stockpile by almost 9,500 warheads – almost exactly the number the Kennedy administration increased the stockpile. In one year (1992), Bush cut 5,300 warheads, more than any other president – ever. Much of the Bush cut was related to the retirement of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The Clinton administration came into office riding the Bush reduction wave, so to speak, and in its first term cut approximately 3,000 warheads from the stockpile. But in his second term, President Clinton slowed down significantly and in one year (1996) actually increased the stockpile by 107 weapons – the first time since 1987 that had happened and the only increase in the post-Cold War era so far. It is still unclear what caused the 1996 increase. When the Clinton administration left office, there were still approximately 10,500 nuclear warheads in the stockpile.

President George W. Bush, who many of us in the arms control community saw as a lightning rod for trying to build new nuclear weapons and advocating more proactive use against so-called “rogue” states, ended up becoming one of the great nuclear disarmers of the post-Cold War era. Between 2004 and 2007 (mainly), the Bush W. administration unilaterally cut the stockpile by more than half to roughly 5,270 warheads, a level not seen since the Eisenhower administration. Yet the remaining Bush arsenal was considerably more capable than the Eisenhower arsenal.

President Barack Obama took office with a strong arms control profile, including a pledge to reduce the number and role of nuclear weapons, taking nuclear weapons off “hair-trigger” alert, and “put and end to Cold War thinking.” So far, however, this policy appears to have had only limited effect on the size of the stockpile, with about 500 warheads retired over six years.

Effect On Stockpile Size

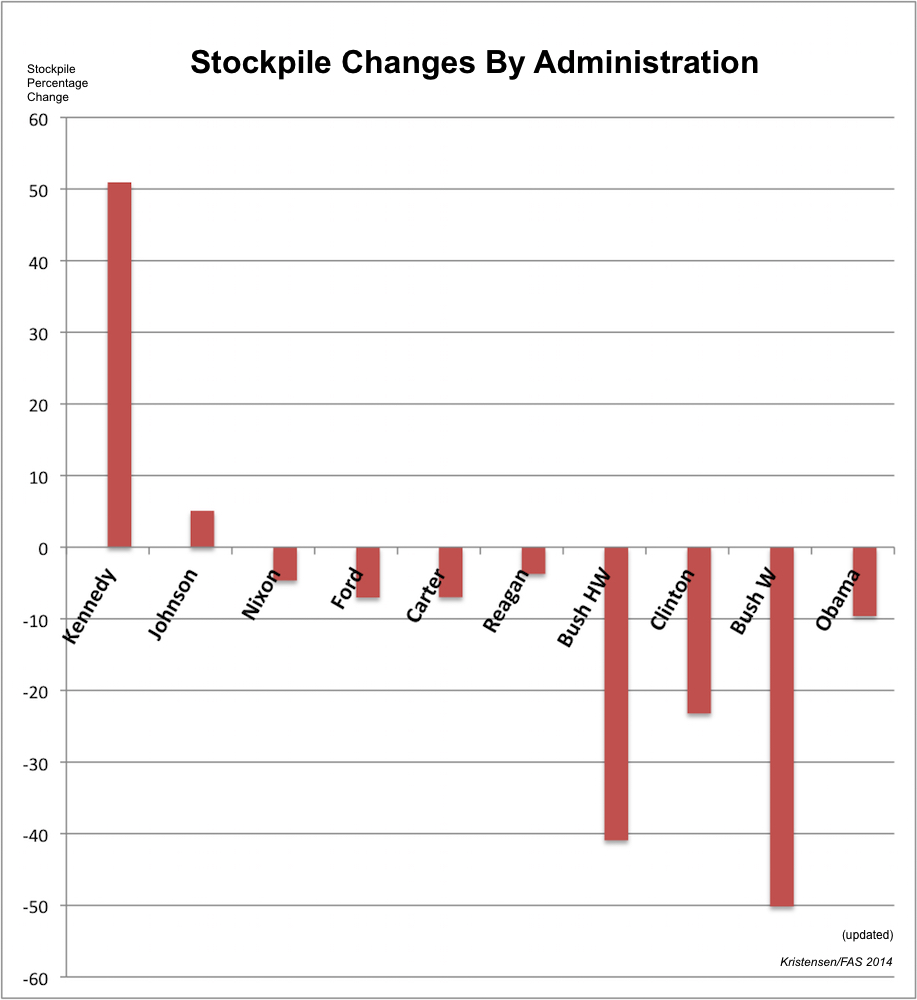

Counting warhead numbers is interesting but since the stockpile today is much smaller than during the previous three presidencies, comparing the number of warheads retired doesn’t accurately describe the degree of change inflicted by each president.

A better way is to compare the reductions as a percentage of the size of the stockpile at the beginning of each presidency. That way the data more clearly illustrates how much of an impact on stockpile size each president was responsible for.

This type of comparison shows that George W. Bush changed the stockpile the most: by a full 50 percent. His father, President H.W. Bush, came in a strong second with a 41 percent reduction. Combined, the Bush presidents cut a staggering 14,801 warheads from the stockpile during their 12 years in office – 1,233 warheads per year. President Clinton reduced the stockpile by 23 percent during his eight years in office.

The Obama administration has had less effect on the nuclear weapon stockpile than any other post-Cold War administration.

Despite his strong rhetoric about reducing the numbers of nuclear weapons, however, President Obama so far had the least effect on the size of the stockpile of any of the post-Cold War presidents: a reduction of 10 percent over six years. The remaining two years of the administration will likely see some limited reductions due to force adjustments and management, but nothing on the scale seen during the tree previous post-Cold War presidencies.

What Went Wrong?

There are of course reasons for the Obama administration’s limited success in reducing the number of nuclear weapons compared with the accomplishments of previous post-Cold War administrations.

The first reason is that the Obama administration during all of its tenure has faced a conservative Congress that has openly opposed any attempts to reduce the arsenal significantly. Even the modest New START Treaty was only agreed to in return for commitments to modernize the remaining arsenal. A conservative Congress does not complain when Republican presidents reduce the stockpile, only when Democratic president try to do so. As a result of the opposition, the United States is now stuck with a larger and more expensive nuclear arsenal than had Congress agreed to significant reductions.

A second reason is that Russian president Vladimir Putin has rejected additional arms reductions beyond the New START Treaty. Because the Obama administration has made additional reductions conditioned on Russian agreement, the United States today deploys one-third more nuclear warheads than it needs for national and international security commitments. Ironically, because of Putin’s opposition to additional reductions, Russia will now be “threatened” by more U.S. nuclear weapons than had Putin agreed to further reductions beyond New START. As a result, Russian taxpayers will have to pay more to maintain a bigger Russian nuclear force than would otherwise have been necessary.

A third reason is that the U.S. nuclear establishment during internal nuclear policy reviews was largely successful in beating back the more drastic disarmament ambitions president Obama may have had. Even before the Nuclear Posture Review was completed in April 2010, a future force level had already been decided for the New START Treaty based largely on the Bush administration’s guidance from 2002. President Obama’s Employment Strategy from June 2013 could have changed that, but it didn’t. It failed to order additional reductions beyond New START, reaffirmed the need for a Triad, retained the current alert and readiness level, and rejected less ambitious and demanding targeting strategies.

In the long run, some of the Obama administration’s policies are likely to result in additional unilateral reductions to the stockpile. One of these is the decision that fewer non-deployed warheads are needed in the “hedge.” Another effect will come from the decision to reduce the number of missiles on the next-generation ballistic missile submarine from 24 to 16, which will unilaterally reduce the number of warheads needed for the sea-based leg of the Triad. A third effect will come from a decision to phase out most of the gravity bombs in the arsenal. But these decisions depend on modernization of nuclear weapons production facilities and weapons and are unlikely to have a discernible effect on the size of the stockpile or arsenal until well after president Obama has left office.

The Next Two Years

During its last two years in office, the Obama administration’s best change to achieve some of the stockpile reductions it failed to demonstrate in the first six years would be to initiate reductions now that are planned for later. In addition to implementing the reductions planned under the New START Treaty early, potential options include offloading excess Trident II SLBMs and retiring excess W76 warheads above what is needed for arming the future fleet of 12 SSBNX submarines; there are currently nearly 50 Trident II SLBMs too many deployed and about 800 W76s too many in the stockpile, so many that the Navy has asked DOE to accept transfer of excess W76s from navy depots faster than planned to free up space and save money. It also includes retiring excess warheads for cruise missiles and gravity bombs above what’s required for the B61-12 and LRSO programs; most, if not all, B61-3, B61-10, B83-1, and W84 warheads could probably be retired right away. Moreover, several hundred W78 and W87 warheads for the Minuteman ICBMs could probably be retired because they’re in excess of what’s needed for the force planned under New START.

But in addition to retiring excess warheads, there are also strong fiscal and operational reasons to work with congressional leaders interested in trimming the planned modernization of the remaining nuclear forces. Options include reducing the SSBNX program from 12 to 10 or 8 operational submarines, reducing the ICBM force to 300 by closing one of the three bases and ending considerations to develop a new mobile or “hybrid” ICBM, delaying the next-generation bomber, canceling the new cruise missile (LRSO), scaling back the B61-12 program to a simple life-extension of the B61-7, canceling nuclear capability for the F-35 fighter-bomber, and work with NATO allies to phase out deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe. Such reductions would have the added benefit of significantly reducing the capacity needed for warhead life-extension programs and production facilities.

Achieving some or all of these reductions would free up significant resources more urgently needed for maintaining and modernizing non-nuclear forces. The excess nuclear forces provide no discernible benefits to day-to-day national security needs and the remaining forces would still be more than adequate to deter and defeat potential adversaries – even a more assertive Russia.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

A military depot in central Belarus has recently been upgraded with additional security perimeters and an access point that indicate it could be intended for housing Russian nuclear warheads for Belarus’ Russia-supplied Iskander missile launchers.

The Indian government announced yesterday that it had conducted the first flight test of its Agni-5 ballistic missile “with Multiple Independently Targetable Re-Entry Vehicle (MIRV) technology.

While many are rightly concerned about Russia’s development of new nuclear-capable systems, fears of substantial nuclear increase may be overblown.

Despite modernization of Russian nuclear forces and warnings about an increase of especially shorter-range non-strategic warheads, we do not yet see such an increase as far as open sources indicate.