Declining Deterrent Patrols Indicate Too Many SSBNs

By Hans M. Kristensen

Does the U.S. Navy have more ballistic missile submarines than it needs? Dramatic reductions in deterrent patrols – but not submarines – suggest so.

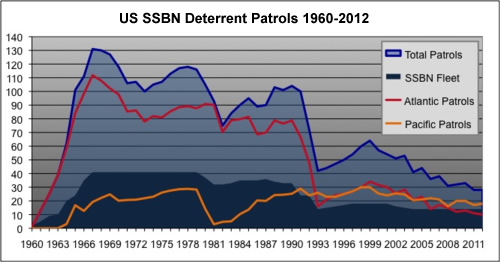

Over the past thirteen years, the number of deterrent patrols conducted each year by U.S. ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) has declined by more than half.

During most of the same period, the size of the SSBN fleet has remained relatively steady at 14 boats, after four were retired in 2001-2003. Yet the decline in deterrent patrols has continued.

As a result, each SSBN now conducts one deterrent patrol less per year, in average, than it did a decade ago. At any given time, there are fewer SSBNs on deterrent patrol today than in the early-1960s when SSBN patrols first began.

The development indicates that the U.S. Navy may currently be operating more SSBNs than are needed for U.S. security needs, and that the current patrol rate could in fact be maintained with fewer submarines.

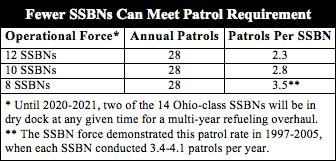

This also raises questions about the navy’s plan to build a new class of 12 SSBNs to replace the current class of 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. Fewer than 12 submarines would be able to meet the current deterrent patrol level and the number of patrols may even decline further in the future.

Declining Deterrent Patrols

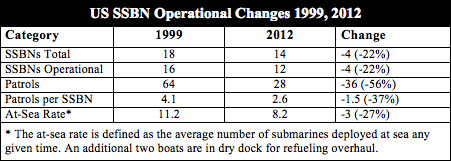

Since 1999, the number of deterrent patrols the U.S. SSBN fleet conducts each year has declined by more than 56 percent from 64 patrols in 1999 to 28 in 2012. The decline has reduced the number of annual patrols to the lowest level since 1962 (see graph).

The decline has been most significant in the Atlantic where the number of annual patrols has dropped from 34 in 1999 to only 10 in 2012, a decline that was expected because King’s Bay has lost four SSBNs since 1999 and now operates only six boats.

But even in the Pacific, where most SSBNs are now based and the fleet has remained steady at eight boats, the decline has also been significant, from 30 patrols in 1999 to 18 patrols in 2012.

Effects on Operational Tempo

Ohio-class SSBNs were optimized for long deterrent patrols and each boat has two crews (Gold and Blue) to enable the submarines to spend as little time in port as possible.

Yet each SSBN now spends less than half of the year on deterrent patrol – the purpose for which it was built – compared with 60-70 percent a decade ago. The decline means that each submarine today conducts an average of 2.3 deterrence patrols per year, down from 4.1 a decade ago. In fact, today’s patrol rate is the lowest ever for the Ohio-class SSBNs.

Each patrol lasts an average of 70 days but the duration can fluctuate significantly, from as little as 30 days to more than 100 days, due to targeting requirements and technical issues.

The longest-ever known patrol conducted by a U.S. SSBN took place in 2010 when the USS Maine (SSBN-741) deployed continuously for 105 days between August and December.

Patrol Rate Versus At-Sea Rate

The decline in deterrent patrols should theoretically result in 5-6 SSBNs (36-43 percent) deployed at any given time and the remaining 8-9 boats visible in port. But the patrol rate does not match the at-sea rate; there are more SSBNs at sea than on patrol.

Between 1998 and 2001, the U.S. Navy periodically disclosed how many SSBNs were at sea at any given time: an average of 11 boats out of a fleet of 18 SSBNs (about 61 percent). The terrorist attacks in September 2001 put an end to that transparency and subsequent requests to the navy for the information were denied.

Yet high-resolution commercial satellite images have since become widely available to the general public via Google Earth and other sources. Examination of more than two dozen satellite images from 1993-2012 shows that an average of ten SSBNs (71 percent) are normally absent from the two bases. Two of those SSBNs are in dry dock for refueling while the remaining eight (57 percent) are deployed at sea.

So why doesn’t the patrol rate not match the at-sea rate? The reason is that deterrent patrols are not the only thing that SSBNs do. Between patrols and maintenance, each submarine deploys on sea-trials, midshipmen cruises and exercises. Yet the decline in deterrent patrols means that SSBNs are now doing more of the other things than they did a decade ago.

Fewer SSBNs Can Do The Job

The dramatic decline in deterrent patrols over the past decade suggests that the U.S. Navy can meet its deterrence requirements with fewer SSBNs than the 14 boats it currently operates. In fact, if each SSBN conducted as many patrols as a decade ago, no more than eight operational SSBNs would be needed to conduct the 28 deterrent patrols required today. With two additional SSBNs in refueling overhaul at any given time, the fleet could be reduced from 14 to 10 boats, saving millions of dollars in operational, maintenance, personnel, and inspections.

Even if the navy needed to retain an additional two SSBNs as a couching against technical problems, the fleet could probably be reduced to 12 boats. Indeed, the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review forecasts such a reduction:

Depending on future force structure assessments, and on how remaining SSBNs age in the coming years, the United States will consider reducing from 14 to 12 Ohio-class submarines in the second half of this decade. This decision will not affect the number of deployed nuclear warheads on SSBNs.

The reason a reduction of two submarines would not affect the number of deployed nuclear warheads on SSBNs is that the two “reduced” SSBNs are the ones that are not deployed but in dry dock for refueling at any given time. The last of those multi-year refueling overhauls is scheduled for the end of this decade, so the NPR projection appears to make a virtue out of necessity. Indeed, unless the two submarines are retired, the navy would actually operate 14 deployed SSBNs during most of the 2020s, or more than is required for national security.

The navy is planning a new generation of 12 SSBNs to replace the current 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. The new submarine will have a new reactor core that can last the entire life of the ship; no multi-year refueling overhaul will be needed (individual submarines will still need to go into dry dock for shorter periods for maintenance and upgrades). The new SSBNs will also be equipped with a new electrical drive and probably be significantly quieter than the Ohio-class. These factors will allow additional reductions.

Moreover, the next-generation SSBNs will only carry 16 missiles each, down from 24 today and 20 by 2018. The first new SSBN will not deploy on patrol until 2031 but it nonetheless indicates that U.S. Strategic Command has already determined that there are 30 percent too many sea-launched ballistic missiles. “The Milestone A decision [12 SSBNs with 16 missiles each] did not assume any specific changes to targeting or employment guidance,” STRATCOM commander Robert Kehler testified before Congress in November 2011. If so, why continue to deploy with the extra missiles for another two decades?

The eight SSBNs that are currently at sea carry 192 missiles with an estimated 860 warheads. Of those, four-five SSBNs with 96-120 missiles and 430-540 warheads are on alert holding targets at risk in Russia, China and North Korea. Eight next-generation SSBNs could carry the same number of warheads on 128 missiles by increasing the warhead loading on each missile. But by 2031, nearly two decades from now, the targeting requirement is likely to be lower than today.

Conclusions and Implications

The significant reduction in SSBN deterrent patrols over the past decade suggests that the U.S. Navy currently operates more SSBNs than are needed.

Compared with a decade ago, each submarine is doing less of what it was designed to do – conducting deterrent patrol with ready nuclear weapons – and spending more time in port and on exercises.

The declining deterrent patrols, combined with a decision to reduce the number of sea-launched ballistic missiles by a third over the next two decades without reduced targeting requirements, indicate that the current SSBN posture is bloated and in excess of national security needs.

The navy could easily cut the SSBN fleet from 14 to 12 boats now and reduce the requirement for the next-generation SSBN from 12 to 10 boats and save billions of dollars in the process.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

FAS estimates that the United States maintains a stockpile of approximately 3,700 warheads, about 1,700 of which are deployed.

The Department of Defense has finally released the 2024 version of the China Military Power Report.

With tensions and aggressive rhetoric on the rise, the next administration needs to prioritize and reaffirm the necessity of regular communication with China on military and nuclear weapons issues to reduce the risk of misunderstandings.

Congress should ensure that no amendments dictating the size of the ICBM force are included in future NDAAs.