Ambitious Warhead Life Extension Programs

|

| Click on image to download document. |

.

By Nickolas Roth, Hans M. Kristensen and Stephen Young

Note: This is the second of four posts analyzing the FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan, each jointly produced by the Federation of American Scientists and Union of Concerned Scientists. See the other posts: 1, 3, 4.

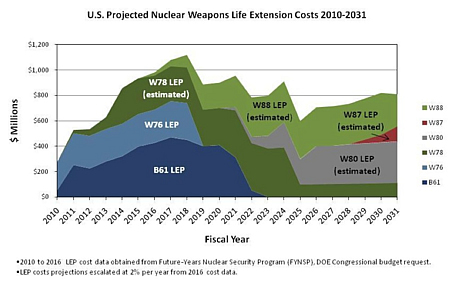

According to the FY2012 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan (SSMP), from 2011 to 2031, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) plans to spend almost $16 billion on Life Extension Programs (LEPs) to extend the service life and significantly modify almost every warhead in the enduring stockpile. This includes an estimated $3.7 billion on the W88 warhead, $3.9 billion on the B61 bomb, $4.2 billion on the W78 warhead, $1.7 billion on the W76 warhead, and $2.3 billion on the W80-1 warhead.

These figures do not include almost $11 billion in additional NNSA expenses simply to maintain the stockpile, outside of the LEP programs. This brings total spending on nuclear warheads over the next twenty years to $27 billion. These budget figures reflect a significant investment in maintaining and modifying the nuclear stockpile.

|

| The FY2012 SSMP contains a large number of graphs including this one, which adopts the style from the graph FAS and UCS produced in our analysis of the FY2011 plan. |

.

The FY2012 SSMP provides one possible indication that LEP programs are becoming more ambitious and will incorporate more intrusive changes to the warheads. For each weapon type, different variants are designated by a modification, or “Mod” number, as indicated by a hyphen followed by a number at the end of the warhead type, e.g., B61-7 is the “B61 Mod 7.” Only significant changes would result in a new Mod number. For example, the W87 warhead underwent a LEP a decade ago that fixed several structural issues but did not receive a new Mod number. The original warhead designs did not used to have a Mod designation, but the FY12 SSMP lists all the existing warhead types that did not previously have a Mod designation with a “-0” extension. This seems to indicate that all LEPs will now produce warheads with new Mod numbers, apparently in anticipation of significant modifications.

These increasingly intrusive modifications are driven by a stated requirement to improve the safety, security and reliability of the warhead designs. Up to a point, this effort enjoys widespread congressional and White House support—after all, who can be against increasing the safety, security and reliability of nuclear weapons? NNSA and the labs are using these requirements as a primary justification for creating wide-ranging simulation, design, engineering, and production programs that, while smaller in output capacity than those during the Cold War, will be exponentially more technically capable.

The SSMP describes how this capability will provide a “comprehensive science basis underpinning deployment of new safety technologies in the stockpile.” This goal also improves the justification of existing facilities—and those still coming on-line—such as DARHT, NIF, Omega, and the Z machine. NNSA’s goal is to incorporate an enormous array of new safety, security, and use control features in almost the entire stockpile by 2031.

The details of these technologies, their justifications, and costs are largely hidden from public scrutiny. A table listing the safety, security, and reliability features of existing warhead types—and of “an ‘Ideal’ System” (warhead)—is contained in the classified Annex B to the SSMP. (For a list of safety and security features probably installed on U.S. warheads, see here.) While some enhancements may be warranted, the justification for all these new features appears to be based on an open-ended development of new technologies for the incorporation of enhanced surety features into warheads independent of any threat scenario.

This pursuit of a wide range of surety improvements justifies the need for substantial warhead modifications and additional production and simulation capabilities. Yet there must be a point of diminishing returns, where the potential improvements are not justified by the monetary costs or the risks to the reliability of the stockpile.

Indeed, stockpile managers and designers used to warn against modifying warheads, noting that doing so could undermine the confidence in reliably predicting the performance of the weapons without nuclear testing. But warhead modification is now a central goal of the stockpile stewardship management program. Indeed, the goal of the LEPs, the FY2012 SSMP states, it to provide options for “maintaining and modifying the future stockpile” (emphasis added). Modification—not just maintenance—of the enduring stockpile has become a core objective. Interestingly, the SSMP bluntly acknowledges that such modifications of the warheads will reduce confidence in the reliability of the stockpile by changing warheads from the designs that were tested:

“An aggressive ST&E [Science, Technology and Engineering] program is replacing…empirical factors [used to calibrate simulation codes based on underground nuclear tests] with scientifically validated fundamental data and physical models for predicting capability. As the stockpile continues to change due to aging and through the inclusion of modernization features for the enhanced safety and security, the validity of the calibrated simulations decreases, raising the uncertainty and need for predictive capability. Increased computational capability and confidence in the validity of comprehensive science-based theoretical and numerical models will allow assessments of weapons performance in situations that were not directly tested.” (Emphasis added).

However, NNSA’s enthusiasm for extensively modifying all warheads may be going beyond what Congress and the Obama administration as a whole will support. The foundation for such objections is clearly laid out in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, which states explicitly that the United States “will study options for ensuring the safety, security, and reliability of nuclear warheads on a case-by-case basis.” (p. xiv). This seems to contradict NNSA’s pursuit of every available surety feature for every warhead.

In an example of rising concerns, the May 2011 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on the B61 LEP raised red flags about the NNSA’s proposed changes to the bomb. The report expressed concern about the scope of the LEP, noting that it was the first ever that sought to simultaneously refurbish multiple components, enhance safety and surety, and make other design changes. The report noted that some of the proposed new surety features, such as multipoint safety, have never been used in existing stockpile weapons.

Multipoint safety seeks to lessen the chance of an accidental nuclear explosion if the conventional explosive accidentally ignites at more than one point nearly simultaneously. The current one-point safety requirement mandates that the risk of a nuclear detonation be no greater than one in a million if the conventional explosive accidentally ignites at one point, which the SSMP acknowledges is an “extraordinarily high reliability requirement.” As the GAO notes, warheads in the current stockpile do not have multi-point safety, and even the NNSA does not consider the technology mature.

Because of these issues, the Senate appropriations committee recently expressed its concern about the B61 LEP. The committee’s report notes that “NNSA plans to incorporate untried technologies and design features to improve the safety and security of the nuclear stockpile” (emphasis added). While expressing support for improved surety, the report states that it “should not come at the expense of long-term weapon reliability.” Due to this concern, the committee reduced funding for the B61 LEP by almost 20% and called for both an independent assessment of the proposed safety and security features and a cost-benefit analysis of them.

One gets the sense that, since Congress stopped the Reliable Replacement Warhead, NNSA has seized on safety and security as the sure-fire cause to allow major warhead modifications and win significant funding. Based on the new Senate findings, NNSA may discover there are limits to how far Congress will go down the modification path and what it will spend, even on the golden ticket of improved safety.

About the authors: Nickolas Roth is Policy Fellow for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a graduate student at the University of Maryland, Hans M. Kristensen is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, and Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst at Union of Concerned Scientists.

See also: FY2011 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan | Previous blog in this series

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

As long as nuclear weapons exist, nuclear war remains possible. The Nuclear Information Project provides transparency of global nuclear arsenals through open source analysis. It is through this data that policy makers can call for informed policy change.

FAS estimates that the United States maintains a stockpile of approximately 3,700 warheads, about 1,700 of which are deployed.

The Department of Defense has finally released the 2024 version of the China Military Power Report.

With tensions and aggressive rhetoric on the rise, the next administration needs to prioritize and reaffirm the necessity of regular communication with China on military and nuclear weapons issues to reduce the risk of misunderstandings.