Who was Willy Higinbotham?

Editor’s note: The following is a compilation of letters by Dr. William Higinbotham, a nuclear physicist who worked on the first nuclear bomb and served as the first chairman of FAS. His daughter, Julie Schletter, assembled these accounts of Higinbotham’s distinguished career.

Thank you for this opportunity to share with you my father’s firsthand accounts of the inception of the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). After my father died in November 1994, I inherited a truly intimidating treasure of letters, correspondence and most importantly a nearly complete manuscript (mostly on floppy disks) of his unpublished memoirs. Over the last couple of decades, I have read widely and deeply, collected resources, transcribed and sorted through this material and am planning to publish a personal history of Willy in the near future.

William Higinbotham

Having studied this man from a more distant perspective, I am sure about certain things. Willy was at his heart an optimist, a democrat, a child of liberal New England Protestants during the Great Depression, and a man who didn’t mind doing a lot of behind the scenes dirty work to make things happen. He did this with self-deprecating humor, confidence in the humanity of others, a terrific sense of play, music, camaraderie, and most importantly a deep respect for the opinions of everyone. He was humble, incredibly brilliant and could recall details from meetings many years in the past as well as lyrics to jazz standards and sea chanties not sung in a while.

Dad was a terrific story teller. This is his version of how he came to Washington, DC to serve as the first chairman of FAS. These are mostly his words with some additional anecdotes from colleagues and friends who knew him well during the war years and after.

In a letter to his daughter Julie in April 1994, Willy began his account with his parents, a beloved Presbyterian minister and wife:

“It is from them and their example that I have been inspired to do something for humanity. In my case, the opportunity did not arise until I was 30 and the Second World War had started. As a graduate student at Cornell I was too poor to consider marriage and had no prospects for a reasonable job. As soon as Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, I knew that the US should prepare to go to war with our European allies. However, the vast majority of US citizens and Congressmen believed that we should have nothing to do with any European conflicts. It was only with difficulty that President Roosevelt was able to provide some assistance to the UK by “Lend Lease.” I was delighted to be invited to go to MIT in Jan. 1941, as Hitler’s Luftwaffe was bombing London and other British cities.

The US finally initiated the draft in March or April and (my brother) Robert was one of the first to be called up. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor that fall, we were in the war for good. (My brother) Freddy was the next to be drafted. By the summer of 1943 he was a navigator on a small C47 transport plane that dropped parachuters on Sicily, and then (my brother) Philip was drilling with the Army Engineers. I had strong reasons to develop technology that would speed defeat of Germany and Japan.

As you know, it was when I saw the first nuclear test on July 16, 1945, that I determined to do what I could to prevent a nuclear arms race.”

Willy and his wife Julie

From his unpublished memoirs, Willy described the Trinity test:

“Until the last moment, it was not clear if the implosion design [which used plutonium] would actually work. Everyone was confident that the gun design [which used highly enriched uranium] would work, but Hanford was producing plutonium at a good rate while Oak Ridge was producing highly enriched uranium with great difficulty. Consequently, the Trinity test was planned for early in 1945.

Almost everyone in Los Alamos was involved in constructing the implosion weapon or in designing and installing measurement instruments for the test. Most of my group was involved in the latter. Sometimes I drove, with others, to the site to install and test various devices. Many of the instruments were to be turned on minutes or seconds before the bomb was to be triggered. Joe McKibben, of the Van de Graff group, designed the alarm-clock and relay system which was to send out signals for the last ten minutes. I designed the electronic circuit which was to send out the signals during the last second and then to send the signal to the tower. Some of my scientists and many of my technicians spent many days at the site. By test day, we had done all that was requested and I was prepared to await the results of the test, at Los Alamos.

At the last minute, I had a call from Oppie [Scientific Director J. Robert Oppenheimer], asking me to bring a radio to the test site for a number of special observers who were to be at 18 miles from the tower. We had an all-wave Halicrafters receiver which needed a storage battery for the filaments and a stack of big 45 volt B-batteries for the plates. We also had several cheap loud speakers. So, I grabbed several of the remaining technicians and had them check the equipment and pack it into a small truck. They drove the truck to the site. I went with some of the special guests by bus to Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, whence a military bus took us to the place reserved for us, near where the road to the test site leaves the main highway north of it.

We arrived there in the evening. As has been reported often, the weather clouded over and there was some rain. So we waited. The radio worked although the sound was rather weak. The Halicrafter had less than a watt of output and the speakers were not very efficient. Eventually, the countdown began. We were issued slabs of very dark glass, used by welders. I couldn’t see the headlights on the truck through it. I only remember one of the others who was in our select group, Edward Teller. As the countdown approached the last 10 seconds, he began to rub sun screen on his face, which rather shook me. I had been assured that the bomb, if it worked, would not ignite the atmosphere or the desert. At 18 miles it seemed incredible to me that we might get scorched.

At T = 0, we saw a brilliant white flash of light through our dark glass filters, and the hills around us were suddenly brightly lit. Immediately, the point of light expanded to a white sphere and then to a redder inverted bowl shaped object which began to be surrounded with eddies and then rose up into the air and climbed rapidly to the sky, where a clear space suddenly opened in the high thin cloud layer and finally ended as an ugly white cap. All up and down the smoky column there were bluish sparks due to the radioactivity and electric discharges. It must have been more than a minute before the shock wave came through the ground, followed shortly by the sharp air-wave blast, which rumbled off the hills for another minute or so. It was clear that the bomb worked as predicted. I had hoped that the physicists might have been wrong and for many reasons I figured that this test would not be successful. Now I had to face the existence of nuclear weapons. It was a paralyzing realization.

As I recall, no one said anything. My boys packed up the radio equipment and headed home. I got into a bus with about fifteen others and we started for Albuquerque. I had saved one of the bottles of scotch, which my MIT friends had given me in 1943, and had it with me, in case. I pulled it out, opened it, and passed it around. The others on the bus, scientists and military types, quietly sipped it and passed it along until it was empty. No one said anything.

Several hours later we arrived at Kirtland and those of us from Los Alamos transferred to another bus to return there. I was paralyzed. I went back to the Lab and doodled there until closing time. I had supper and went to my room. I didn’t sleep. All I could think of was that the Soviet Union would surely develop nuclear weapons and might blow us off the map. I knew about radar and anti-aircraft and that a bomb, such as the one I had seen, would wipe out any city. The best defense against bombers in Europe had been to shoot down ten percent of the attackers. Ninety percent would not save us.

After agonizing for a day or more, I finally began to think about why Stalin might attempt to destroy the US. It was quite possible that Soviet aircraft could cross the oceans and attack the US. However, it would do them no good to just destroy cities. They would have to occupy us to gain any advantage. The more I thought about this, the more I came to believe that attacking the US with nuclear weapons would not make sense even to an evil man like Stalin. What might make more sense would be to use nuclear weapons to attack our allies in Europe. By then it was clear that Stalin intended to continue to occupy Poland, Hungary and other previously free countries that surrounded the Soviet Union. (In my mind) at least the US did not seem to be threatened. There would be time to see if the Soviet Union was going to threaten the other nations beyond those it now controlled. (Eventually) I got some sleep and went back to work on the new jobs which faced the Lab.

I had no intention of taking a major role in this effort. As soon as Japan surrendered, many of the scientists at Los Alamos began to discuss this subject. When General Groves said that we could keep the secret for 15 years, and Congressmen told scientists to design a defense, we held a big meeting and started to draft a statement for the public.”

In a letter Dad wrote to his mother from Los Alamos:[ref]Jungk, Robert. Brighter Than a Thousand Suns. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1958 p 223.[/ref]

“I am not a bit proud of the job we have done . . . the only reason for doing it was to beat the rest of the world to a draw . . . perhaps this is so devastating that man will be forced to be peaceful. The alternative to peace is now unthinkable. But unfortunately there will always be some who don’t think. . . . I think I now know the meaning of “mixed emotions.” I am afraid that Gandhi is the only real disciple of Christ at present . . . anyway it is over for now and God give us strength in the future. Love, Will.”

From his memoirs, Willy described how he came to Washington, DC in the fall of 1945:

“Strangely, I don’t remember many discussions of the implications of nuclear weapons at Los Alamos before the end of the war. My friends and I had some scattered discussions about how Nazism had taken hold, and of what the world might face after Hitler was defeated. I was invited a few times to sit in Oppie’s living room as Niels Bohr discussed his thoughts about the future control of atomic energy. Bohr was almost impossible to understand because he had an accent and because he always spoke several decibels below the audible threshold. Much later I would understand how wise he was, but at the time the whole subject seemed confusing and not very important to me.

Then came Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Japanese surrender. We had a big party the night the surrender was announced. I sat on the hood of a jeep, playing my accordion, as we paraded around town. Immediately after that, the discussions began in earnest. A number of them were held in my office in the Tech area in the evenings. The public response to the development of atomic weapons was discouraging. General Groves asserted that it would take the Soviets fifteen years to develop an atomic weapon. Congressmen began talking about defenses. Scientists at Oak Ridge and Chicago were organizing and we began to hear from them.

The first large meeting was attended by about sixty people on August 20th. All agreed that we should form an organization and the question of whether it should consider scientists’ welfare as well as the social implications of nuclear energy, was discussed. A committee was appointed to make arrangements for a meeting for all of the scientists and engineers.

On August 23rd, a nine member committee issued an invitation to attend a meeting for all scientists and engineers on August 30th for the following purpose:

“Many people have expressed a desire to form an organization of progressive scientists which has as its primary object to see that the scientific and technological advancements for which they are responsible are used in the best interests of humanity.

Most scientists on this project feel strongly their responsibility for the proper use of scientific knowledge. At present, recommendations for the future of this project and of atomic power are being made. It would be the immediate purpose of this society to examine our own views on these questions and take suitable action. However, the future will hold more problems and scientists will feel the need of a more general organization to express their views.

Before the next meeting had been held it was clear to everyone that the international control of atomic energy was the vital issue and should be the only issue with which the organization was concerned.”

The meeting on August 30th was attended by about five hundred individuals. They overwhelmingly approved the following motion by Joe Keller:

- We hereby form an organization of scientists, called temporarily, the Association of Los Alamos Scientists (ALAS).

- The object of this organization is to promote the attainment and use of scientific and technological advances in the best interests of humanity. We recognize that scientists, by virtue of their special knowledge, have, in certain spheres, special social responsibilities beyond their obligations as individual citizens. The organization aims to carry out these responsibilities by keeping its members informed and by providing a forum through which their views can be publicly and authoritatively expressed.

We discussed what our statement should say to the President and to the public. Except for Edward Teller, we all agreed that the message was that (1) there is no secret (scientists anywhere could figure out how to make atomic weapons now that we had demonstrated that they are possible). In addition, (2) there is no defense that can prevent great devastation by atomic weapons, and (3) we must have “world control.” Edward Teller would not agree with the latter because that was a political and not a technical conclusion. Leo Szilard’s counter to this, we later heard, was that you don’t shout “fire” in a crowded theater without telling people where the exits are. Anyway, the three phrases became our policy.

To my great surprise, I was elected the first chairman of the Association of Los Alamos Scientists. Later, I went to Washington and offered to spend a year managing the scientists’ office. Then I was elected the first chairman of the Federation of American Scientists in January, 1946. I was surprised and hoped that I would not let people down. I think that I understand this. I do not have strong beliefs as did Leo Szilard and many others. I was not a Nobel laureate. I was a team worker. I sought to unite people on positions that they could agree to. People trusted me.

The first executive committee was composed of David Frisch, Joseph Keller, David Lipkin, John Manley, Victor Weisskopf, Robert Wilson, William Woodward, and myself (chairman).

From the beginning, we were aware that the scientific and military success of our work would bring both new dangers and new possibilities of human benefits to the world.

We posed and answered five questions:

- What would the atomic bomb do in the event of another war?

- Use of such bombs would quickly and thoroughly annihilate the important cities in all countries involved. We must expect that bombs will be developed which will be many times more effective and which will be available in large numbers.

- What defense would be possible? One hundred percent interception should be considered impossible. Therefore, were there a possibility of attack we could not gamble on defenses alone and would have to make drastic changes such as abandoning cities and decentralizing communications. How long would it take for any other country to produce as atomic bomb? Within a few years.

- What would be the effect of an atomic arms race on science and technology? Emphasis on the development of more weapons would interfere with developments for peaceful applications.

- Assuming that international control of the bomb is agreed upon, is such control technically feasible? From a scientific point of view we assert that international control of the atomic bomb is feasible and that such control need not interfere with free and profitable peacetime research and development.

Like everyone else, I visited congressmen, talked to reporters, lectured to local organizations and answered phone calls. A large part of the public was interested in atomic energy. A number of the leaders of major national organizations visited us or asked us to meet with them.

When the Soviets fired their first nuclear test in 1949, the President and the Congress pushed for development of the H bomb, which stimulated the nuclear arms race. It was a sad story after that. Edward Teller was convinced that the Soviets would blow up the US if it ever had the opportunity to do so without suffering much retaliation. More rational people felt that the Soviets would have enough trouble keeping on top of their people and satellites, especially after Stalin died in 1970. I could go on. The US became paranoid about communists. Joseph McCarthy lied but many innocent people lost their jobs. Oppenheimer was publicly disgraced. The US continued to accelerate the nuclear arms race. By good luck, the US and USSR agreed to halt tests in the atmosphere in 1963 and the Cuban missile crisis did not lead to the Apocalypse, though that was close. I have spent a lot of my time and effort trying to influence US policy in this area. A lot of that was spent talking to the already converted. My friends and I have had some minor successes. But we never could convince our government that the nuclear arms race was unnecessary and that the Soviets would respond favorably if we were to suggest winding it down. It was the Soviet leaders, with Gorbachev, who realized that the arms race was a waste of effort and who were willing to take the risk of offering to reduce their deployed nuclear weapons and go further if the US agreed.

If we and others are to survive, we must understand the present situation and try to find new and better ways to deal with international problems. The development of nuclear weapons means that the traditional policies will probably fail. I have had a few opportunities to discuss this with some of the doubters. Most of the time, however, the people that I talked to were sympathetic to our attempts at developing a new approach.

So, the objective that I devoted so much time, effort, and thought to was finally attained by the Soviets. Most of the time I was discouraged but did not give up. A number of the scientists who were active at the start gave up. Some of the scientists that I have worked with thought that I was crazy — but they never took the trouble to find out what I knew about what was going on or what I was really doing. There were many distinguished scientists who thought as I did, and we encouraged each other. They have been a great help to me.”

These last few anecdotes come from the many letters that were sent to my father on the occasion of his 80th birthday. I believe they speak to the qualities that made Dad so incredibly successful at ALAS, FAS, and then on to Brookhaven National Laboratory where he worked on an astounding number of projects and committees, and where he established the Technical Support Organization Library. During his tenure at BNL he attended some of the Pugwash meetings, SALT talks and traveled extensively all over the world to communicate honestly with scientists and policy makers regarding atomic energy and nuclear safeguards.

He also built the prototype for Pong in the mid-fifties as a demonstration exhibit for the public and guests at the summer open lab events. He was “discovered” by computer gamers all over the world by around 1972. Dad was mortified by this! He thought anyone with a simple understanding of electronics could have invented that sort of game just as easily as he did! He bemoaned the idea that he would be remembered not for his life’s work on nuclear non-proliferation, but on a silly computer game. And (regrettably) he was right about that.

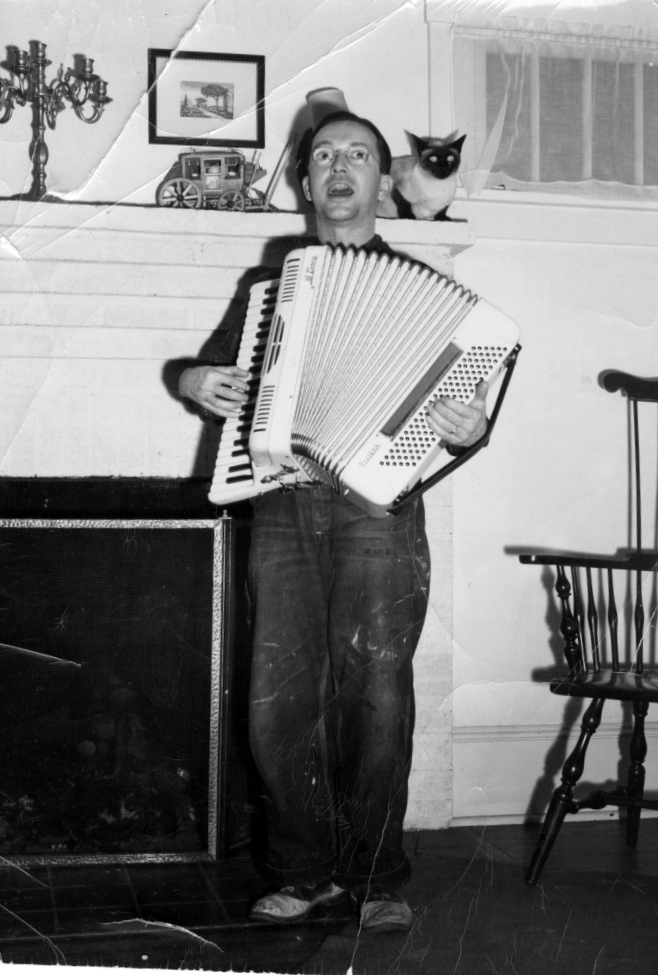

Willy on Long Island with his beloved accordion around 1951

Jim de Montmollin, colleague from the Manhattan Project:

“I think the most important thing to me is your sensitivity and selflessness. In an era when people seek to project an image of sophistication through a cynical and ‘me first’ attitude toward everything, I especially value knowing people like you. I think of myself also as a sort of pragmatic idealist, and I consider you to be the ultimate model. Far more than I, you have worked tirelessly toward unselfish objectives, always seeking practical and feasible steps toward getting there.

I also admire your tolerance. You don’t hesitate to call it like you see it, but neither are you ever hesitant to defend any cause or individual, however unpopular or unfashionable they may be. That is what has always made it such a pleasure to discuss anything with you: it [is] rare to know people who think for themselves, who absorb new information and develop their thoughts from it, who are more than carriers of the conventional wisdom, and who are so well—informed on so many things as you. What I refer to as your tolerance is both an openness toward new facts and ideas and a lack of animosity toward those who differ in any way.

Your dedication and drive over at least the last 50 years toward objectives that are not self-seeking or necessarily fashionable is another aspect that makes you so outstanding to me. Long before I knew you, you did it at no small personal sacrifice. When you became too old to meet the bureaucratic rules for continued work, you have worked as hard as ever, taking advantage of the freedom to apply yourself wherever you could be the most effective. If you ever have any private doubts about what you may have sacrificed, let me assure you that I appreciate and admire you for it.

I remember you commenting on more than one occasion that you regarded George Weiss as a ‘real gentleman.’ I agree, but that also applies to you even more so. It is your sensitivity to others’ feelings, your tolerance of their shortcomings, and your efforts to point out their good qualities that mark you as a gentleman to me, in the finest sense of the word.”

From Freeman Dyson, English-born American theoretical physicist and mathematician:

“I am delighted to hear that the FAS headquarters building is to be named in your honor. In this way we shall celebrate the historic role that you played in the beginnings of FAS. And we make sure that future generations did not forget who you were and what you did.

I remember vividly the day I joined FAS, soon after I arrived in the USA as a graduate student in 1947. Gene Lochlin, who was a fellow student at Cornell, took me to an FAS meeting and I was immediately hooked. One of the things that attracted me most strongly to FAS was the spontaneous and un-hierarchical way in which [it] should function. Coming fresh from England, I found it amazing that the leader of FAS was not Sir Somebody-Something, but this young fellow Willy Higinbotham who had grabbed the initiative in 1945 and organized the crucial dialogue between scientists and congressmen.

And [by] 1947 you were already a legendary figure, a symbol of the ordinary guy who changes history by doing the right thing at the right time. To me you were also a symbol of the good side of America, the open society where everyone is free to make a contribution. You just happen to make one of the biggest contributions. I am proud now to join and honoring your achievement.”

The world has certainly changed since the atomic bomb first exploded over the white sands of New Mexico in July 1945, yet it is clear that in regard to nuclear non-proliferation and world peace we have a mighty long way to go. William Higinbotham served as the first chairman of FAS in 1945; the mission and objectives were clear and imperative. The work he began now continues 70 years later. On behalf of my father, thank you for your most noble efforts to make our world a safer and saner place for all of humanity.

Julie Schletter retired in 2013 after almost forty years working in education as a school counselor. Her recent project has been completing a book about her father, Accordion to Willy: A Personal History of William Higinbotham the Man who Helped Build the Atom Bomb, Launched the Federation of American Scientists and Invented the First Video Game.

The Federation of American Scientists applauds the United States for declassifying the number of nuclear warheads in its military stockpile and the number of retired and dismantled warheads.

North Korea may have produced enough fissile material to build up to 90 nuclear warheads.

Secretary Austin’s likely certification of the Sentinel program should be open to public interrogation, and Congress must thoroughly examine whether every requirement is met before allowing the program to continue.

Researchers have many questions about the modernization of Pakistan’s nuclear-capable aircraft and associated air-launched cruise missiles.