What’s New for Nukes in the New NDAA?

At the time of publication, the NDAA had passed both chambers of Congress but had not yet been signed by the president. The Act, S. 1071, was signed into law on December 18.

Congress’ new annual defense spending package, passed on December 17, authorizes $8 billion more than the Trump administration requested, for a total of $901 billion. The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them. Below is an overview of provisions of note in the new NDAA related to nuclear weapons.

Sentinel / Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

Every year since fiscal year (FY) 2017, Congress has inserted language into the NDAA prohibiting the Air Force from deploying fewer than 400 ICBMs (an arbitrary requirement put in place by pro-ICBM members of Congress fearful of any reductions in the force). The FY26 NDAA does not break this streak; in fact, it entrenches the requirement deeper into US policy. Rather than repeating the minimum ICBM requirement as a simple provision as previous NDAAs have done, Section 1632 of the new legislation inserts the requirement into Title 10 of the United States Code (the US Code is the official codification by subject matter of the general and permanent federal laws of the United States. Title 10 of the Code is the subset of laws related to the Armed Forces). This change means that Congress will no longer have to agree to and insert the requirement into the NDAA year after year. Instead, the requirement becomes the permanent standard and will require an affirmative change in a future NDAA to undo. Beyond requiring the Air Force to deploy at least 400 ICBMs, the new defense spending act additionally amends Title 10 of US Code to prohibit the Air Force from maintaining fewer than the current number of 450 ICBM launch facilities (essentially meaning that the Air Force cannot decommission any of the 50 extra launch facilities in the US inventory).

This change is indicative of a desire by Congress to bolster its protection of the ICBM program in response to increased scrutiny prompted by the ever-growing budgetary and programmatic failures of the Sentinel ICBM program. Interestingly, a provision in the Senate version of the defense authorization bill that would have established an initial operational capability (IOC) date for the Sentinel program of September 30, 2033, did not make it into the final text, suggesting a lack of confidence in the Air Force’s ability to achieve the milestone. With an original IOC of September 2030, the September 2033 date would have aligned with the Pentagon’s 2024 announcement that the Sentinel program was delayed by at least three years. The omission may thus indicate Congress’ anticipation of potential further delays to Sentinel’s schedule beyond the Air Force’s most recent estimate.

Nuclear Armed Sea-Launched Cruise Missile (SLCM-N)

In addition to protecting the most politically vulnerable nuclear weapons programs, the FY26 NDAA also aims to speed up US nuclear modernization and development, in some cases even beyond the requests of the administration. Despite the fact that the Pentagon’s FY26 budget request requested no discretionary funding for the nuclear-armed, sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), the NDAA authorized $210 million for the program — on top of the $2 billion to the Department of Defense and $400 million to the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) included in the July 2025 reconciliation package to “accelerate the development, procurement, and integration” of the SLCM-N missile and warhead, respectively.

Most notably, the new defense authorization act speeds up the SLCM-N’s deployment timeline by two years. Section 1633 of the act repeats the IOC date of September 30, 2034, established by the FY24 NDAA, but also requires DOD to deliver a certain number of SLCM-N — a number to be determined by the Nuclear Weapons Council — by September 30, 2032, to achieve “limited operational deployment” prior to IOC.

Future nuclear development

In addition to speeding up the deployment timeline for SLCM-N, the FY26 NDAA initiates and accelerates the development of new nuclear weapons by creating a new NNSA program in addition to the stockpile stewardship and stockpile responsiveness programs: the rapid capabilities program. The new program — established by section 3113 of the NDAA via insertion into Title 50 of the US Code (War and National Defense) — is tasked with developing new and/or modified nuclear weapons on an accelerated, five-year timeline (compared to the traditional 10-15 year timeline for new weapons programs) to meet military and deterrence requirements.

Numerous provisions in the new NDAA reflect a lack of trust by Congress in DOD and DOE’s ability to execute and deliver nuclear modernization programs. The creation of stricter and more detailed reporting requirements and action items for making progress on various nuclear weapons related programs constitute an increased effort by Congress to micromanage nuclear modernization programs.

One example of nuclear micromanagement in the act are Sections 150-151 regarding the B–21 bomber. Section 150 mandates the Air Force to submit to Congress:

- An annual report on the new B–21 nuclear bomber including:

- An estimate for the program’s average procurement unit cost, acquisition unit cost, and life-cycle costs,

- “A matrix that identifies, in six-month increments, plans for and progress in achieving key milestones and events, and specific performance metric goals and actuals for the development, production, and sustainment of the B–21 bomber aircraft program” (with detailed requirements for how the matrix should be subdivided and what information it must include),

- A cost matrix (also in six-month increments and including specified subdivisions),

- A semiannual update on the aforementioned matrices.

In addition, the provision requires the US Comptroller General to “review the sufficiency” of the Air Force’s report and submit an assessment to Congress. The following section of the NDAA additionally requires the Air Force to submit to Congress — within 180 days of the act’s enactment — “a comprehensive roadmap detailing the planned force structure, basing, modernization, and transition strategy for the bomber aircraft fleet of the Air Force through fiscal year 2040” (once again, including detailed requirements for what information the roadmap must include).

In a similar fashion, Sections 1641 and 1652 lay out strict reporting and planning requirements for sustaining the Minuteman III ICBM force and developing the Golden Dome ballistic missile defense program, respectively.

Such efforts by Congress to increase its management of US nuclear weapons programs could be in response to repeated and ongoing delays, cost overruns, and setbacks, or could simply reflect Congress’ desire to seize more control over the nuclear enterprise to get what it wants (or, likely, a bit of both). To be clear, Congressional scrutiny into nuclear programs is welcome amidst a trend of over-budget and behind-schedule procurement of unnecessary weapon systems by the Pentagon. Congress can and should play an important role in ensuring that the Departments of Defense and Energy are not handed blank checks for nuclear modernization.

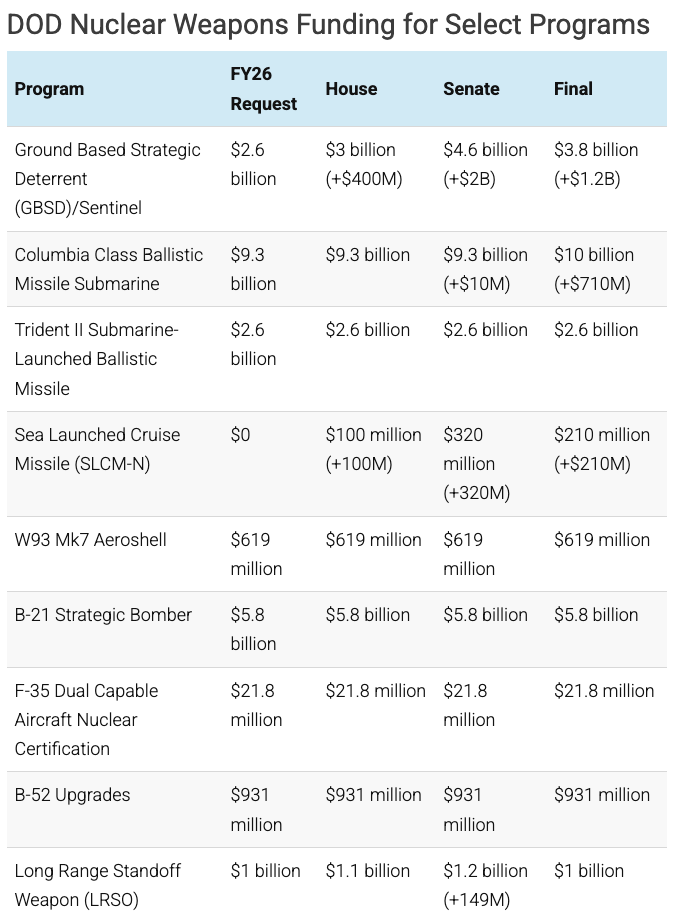

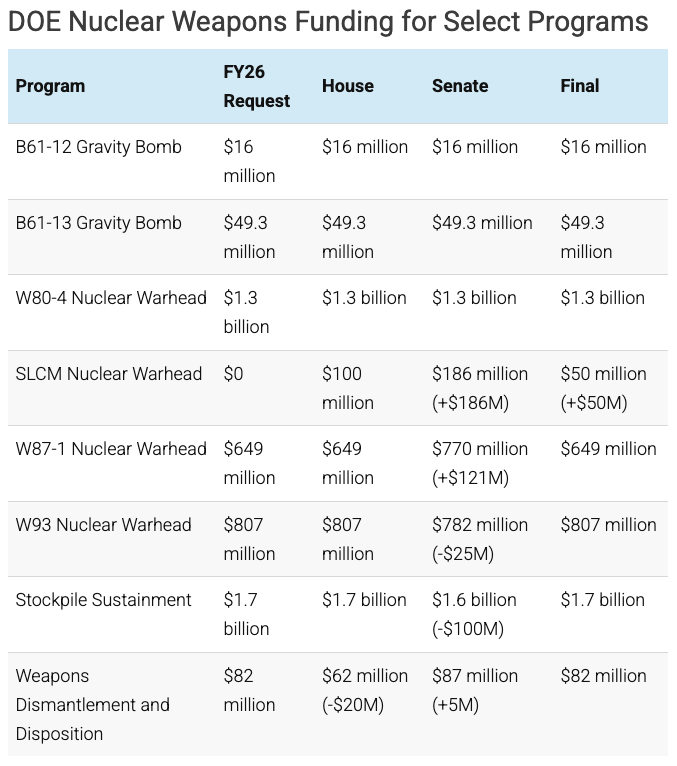

That said, with this legislation, Congress authorized nearly $30 billion in spending for select nuclear weapons programs in FY26 alone. The tables below, developed by the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, show a breakdown of Congress’ authorizations for these programs:

This article was researched and written with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.