A Digital Public Infrastructure Act Should Be America’s Next Public Works Project

The U.S. once led the world in building railroads, highways, and the internet. Today, America lags in building the digital infrastructure foundation that underpins identity, payments, and data. Public Digital systems should be as essential to daily life as roads and bridges, yet America’s digital foundation is fractured and incomplete.

Digital public infrastructure (DPI) refers to a set of core and foundational digital systems like identity, payments, and data exchange that makes it easier for people, businesses, and governments to securely connect, transact, and access services.

DPI consists of interoperable, open, and secure digital systems that enable identity verification, digital payments, and data exchange across sectors. Its foundational pillars are Digital Identity, Digital Payments, and Data Exchange, which together provide the building blocks for inclusive digital governance and service delivery. DPI acts as the digital backbone of an economy, allowing citizens, governments, and businesses to interact seamlessly and securely.

America’s current digital landscape is a patchwork of systems across states, agencies and private companies, and misses an interoperability layer. This means fragmented identity verification, uneven instant payment networks, and siloed data exchange rules and mechanisms. This fragmentation not only frustrates citizens but also costs taxpayers billions, leads to inefficiency and fraud. This memo makes the case that the United States needs sweeping legislation– a Digital Public Infrastructure Act— to ensure that the nation develops a coherent, secure, and interoperable foundation for digital governance.

Challenges and Opportunities

Around the world, governments are investing in digital public infrastructure to deliver trusted, inclusive, and efficient digital services. In contrast, the United States faces a fragmented ecosystem of systems and standards. This section examines each pillar of digital public infrastructure, digital identity, digital payments, and data exchange, highlighting leading international models and what institutional and policy challenges the U.S. must address to achieve a similarly integrated approach.

Fragmented and non-interoperable Digital Identities

Digital Identity. The U.S. has no universal digital identification system. Proving who you are online often relies on a jumble of methods like scanning driver’s licenses, giving your social security number, or one-off logins. Unlike many countries with national e-ID schemes, the U.S. relies on the REAL ID law which sets higher standards for physical driver’s licenses, but it provides no digital ID or consent mechanism for online use. Just under half of U.S. states have rolled out some form of mobile driver’s license (mDL) or digital ID, and each implementation is largely unique.

Federal agencies have tried to streamline login with services like Login.gov, yet many agencies still contract separate solutions (Experian, ID.me, LexisNexis, Okta, etc.), leading to duplication. The Government Accountability Office recently found that two dozen major agencies use a mix of at least five different identity-proofing providers. The result is an identity verification landscape that is inconsistent and costly, both for users and the government.

Fragmented Digital Payment Infrastructure

Digital Payments. The United States still lags in offering universal, real-time payments accessible to all. The payments landscape is highly fragmented, with multiple systems operated by both public and private entities, each governed by distinct rule sets. The Automated Clearing House (ACH) network is the batch-based system that processes routine bank-to-bank transfers such as salaries, bill payments, and account debits or credits. It is co-run by the Federal Reserve (FedACH) and The Clearing House (EPN) under Nacha rules and settles with delay. The Real-Time Payments (RTP) network is an instant 24/7 credit-push system that moves money within seconds through a prefunded joint account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. It was launched by The Clearing House in 2017 and is governed by its private bank owners.

In 2023, the Federal Reserve launched FedNow, the first publicly operated real-time payment rail in the United States, offering instant settlement through banks’ Federal Reserve master accounts. Card networks such as Visa, Mastercard, Amex, and Discover continue to operate proprietary systems, while peer-to-peer platforms like Zelle, Venmo, and CashApp run closed-loop schemes that often rely on RTP for back-end settlement. Because these systems differ in ownership, governance, settlement models, and liability frameworks, they remain largely non-interoperable. A payment sent through RTP cannot be received on FedNow, and card or wallet systems do not seamlessly connect to ACH or instant payment rails.

FedNow operates as a real-time gross settlement (RTGS) infrastructure, enabling participating banks and credit unions to send and receive instant payments around the clock. Its design is infrastructure-centric: the Federal Reserve provides the back-end rail, while banks must opt in, build their own consumer interfaces, and set transaction fees and rules. The system does not define standardized public APIs, merchant QR systems, or interoperable consumer applications. These layers are left to the market. Its policy intent centers on efficiency and resilience in interbank payments rather than universal inclusion or open access.

Examples of Complete Public Payment Ecosystems

By contrast, India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and Brazil’s Pix were designed as full digital public infrastructures that combine settlement, switching, and retail layers within a single public framework. Both are centrally governed, with UPI managed by the National Payments Corporation of India under Reserve Bank of India oversight and Pix managed by the Central Bank of Brazil. They enforce mandatory interoperability across all banks, wallets, and payment apps through open API standards. Their architecture integrates digital identity, authentication, and consent layers, allowing individuals and merchants to transact instantly at zero or near-zero cost.

While FedNow provides the plumbing for real-time settlement among banks, UPI and Pix function as complete public payment ecosystems built on open standards, public governance, and inclusion by design. Real-time payment systems in India (UPI), Brazil (Pix), and the United Kingdom (Faster Payments) now process far higher transaction volumes than their U.S. counterparts, reflecting how deeply these infrastructures have become embedded in daily economic activity.

Credit: fxcintel.com

This fragmented payment ecosystem became painfully apparent during COVID-19: some people waited weeks or months for stimulus and unemployment checks, while fraudsters exploited the delays. Only in 2025 did the Treasury Department finally announce it will stop issuing paper checks for most federal payments, to reduce delays, fraud, and theft.

Clearly, the U.S. needs a more cohesive approach to instant, secure payments, from Government-to-Person (G2P) benefits to Person-to-Government (P2G) tax payments and everyday Person-to-Person (P2P) transactions.

Data Exchange. Americans routinely encounter data silos and repetitive paperwork when interacting with different sectors and agencies. Each domain follows its own regulatory and technical standards. Health records are governed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) established under the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016. Financial data are protected by the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act of 1999 (GLBA) and will soon fall under the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s proposed Personal Financial Data Rights Rule (Section 1033, Dodd–Frank Act). Tax and education data are separately governed by the Internal Revenue Code and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA).

There is no unified, citizen-centric protocol for individuals to consentingly share their data across sectors. For example, verifying income for a mortgage, student loan, or benefits application might require three separate data pulls from the IRS or employer, each with its own process. In healthcare, TEFCA is creating a nationwide data-sharing framework but remains voluntary and limited to medical providers. In finance, Europe’s PSD2 Open Banking Directive (2018) forced banks to open consumer data via APIs, while the United States is only beginning similar steps through the CFPB’s data portability rulemaking. Overall, data-sharing rules remain sector-specific rather than citizen-centric, making it difficult to “connect the dots” across domains.

Data Protection. The United States follows a fragmented, sectoral approach to data protection rather than a single, unified framework. Health information is covered by HIPAA (1996), financial data by GLBA (1999), student records by FERPA (1974), and children’s online data by the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA, 1998).

States have layered on their own privacy laws, most notably the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA, 2018) and the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA, 2020). At the federal level, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) fills gaps using its authority to regulate “unfair or deceptive practices” under Section 5 of the FTC Act (15 U.S.C. §45). However, there remains no nationwide baseline for consent, portability, or deletion rights that applies uniformly across all sectors.

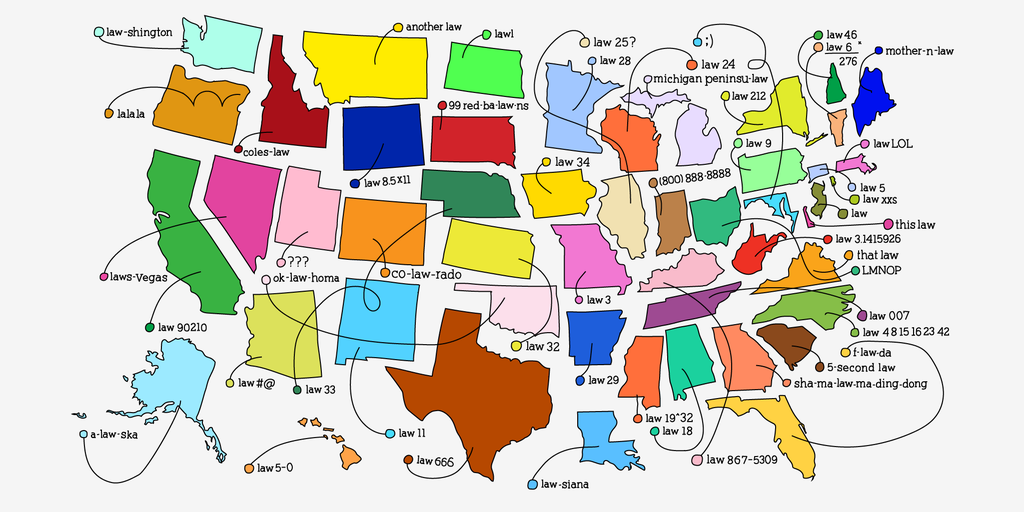

An illustration from 2021 by the New York Times shows the picture very well.

Credit: Dana Davis

Recent efforts in Congress, including the proposed American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA, 2022) and the American Privacy Rights Act (APRA, 2024), sought to create a comprehensive federal framework for data privacy and user rights. APRA built on ADPPA’s foundations by refining provisions related to state preemption, enforcement, and individual rights, proposing national standards for access, correction, deletion, and portability, and stronger obligations for large data holders and brokers. It also envisioned expanded enforcement powers for the FTC and state attorneys general, along with a limited private right of action.

Despite initial bipartisan attention, APRA has not secured sustained bipartisan support and remains stalled in Congress. The bill was jointly introduced in 2024 by the Republican Chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Democratic Chair of the Senate Commerce Committee, reflecting early cross-party interest. However, Democratic support weakened after language addressing civil-rights protections and algorithmic discrimination was removed, prompting several members to withdraw backing (Wired, 2024). As a result, the legislation has not advanced beyond committee referral, leaving the United States reliant on a patchwork of sector-specific and state-based privacy laws.

The outcome is a system where Americans face both fragmented data exchange and fragmented data protection, undermining trust in digital public services and complicating any transition toward a citizen-centric digital infrastructure.

The High Cost of Fragmentation

This patchwork system isn’t just inconvenient; it also bleeds billions of dollars. When agencies can’t reliably identify people, deliver payments quickly, or cross-check data, waste and fraud increase. Here are just a few examples:

Improper Payments. In FY2023 the federal government reported an estimated $236 billion in improper payments. That astronomical sum (almost a quarter-trillion dollars) stemmed from issues like payments to deceased or ineligible individuals and clerical errors. In fact, over 74% of the improper payments were overpayments The largest drivers included Medicare/Medicaid billing mistakes and identity-verification failures in pandemic relief programs. For example, the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program alone saw an increase of $44 billion in erroneous payments, as identity thieves and imposter claims slipped through weak verification checks. While not all improper payments can be eliminated, a significant portion, GAO notes, can be eliminated. The biggest share of improper payments results from documentation and eligibility verification weaknesses, not intentional fraud. All errors could be reduced with better digital identity and data sharing systems.

Identity Theft and Fraud. American consumers are suffering a wave of identity-related fraud. In 2023, the Federal Trade Commission received over 1 million reports of identity theft such as credit cards opened in another person’s name or fraudsters hijacking unemployment benefits. Identity theft now accounts for about 17% of all consumer fraud reports. The surge during the pandemic (when government aid became a target) showed how criminals exploit weak ID verification. State unemployment systems, for instance, paid out a significant sum to fraudsters who used stolen identities. Strengthening the digital ID infrastructure in U.S. could curb these losses by catching imposters before payments go out.

Administrative Overhead. Fragmentation forces each agency and company to reinvent the wheel, at great expense. Consider identity proofing: federal agencies spent over $240 million from 2020–2023 on contracts for login and ID verification solutions, much of it to third-party vendors, despite overlapping functionality. States and private institutions likewise pour resources into redundant systems for onboarding and verifying users. Processing paper documents and manual checks adds further costs and an indirect cost of time and frustration for citizens. A GAO report noted that agencies have widely varying systems and that a coordinated digital identity approach could improve security and save money. In short, the lack of shared public digital infrastructure means higher costs and slower service across the board.

Plan of Action

What would a Digital Public Infrastructure Act do?

It’s clear that the status quo isn’t working. The U.S. needs a Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) Act, a comprehensive federal law that would build the rails and rules for secure, efficient digital interactions nationwide. Just as past Congresses invested in highways and the internet itself, Congress today should invest in core digital systems to serve as public goods. A DPI Act could establish three pillars in particular:

Federated, Privacy-preserving Digital Identity

A secure digital ID that Americans can use (voluntarily) to prove who they are online, without creating a centralized “Big Brother” database. This would be a federated system, meaning you could choose from multiple trusted identity providers. For example, you could share your identification with your state DMV, the U.S. Postal Service, or a certified private entity, all adhering to common standards. The federated system must follow the latest NIST digital identity guidelines for security and privacy (e.g. NIST SP 800-63) to ensure high Identity Assurance Levels.

Crucially, it should be privacy-preserving by design: using techniques like encrypted credentials and pairwise pseudonymous identifiers so that each service you log into only sees a unique code, not your entire identity profile. A federated approach would leverage existing ID infrastructures (state IDs, passports, social security records) without replacing them. Instead, it links and elevates them to a digital plane.

Under a DPI Act, an American citizen might verify their identity once through a trusted provider and then use that digital credential to access any federal or state service, open a bank account, or consent to a background check, with one login. This approach can dramatically reduce fraud (no more 5 different logins for 5 agencies) while protecting civil liberties by avoiding any single centralized ID database. The Act could establish a national trust framework (operating under agreed standards and audits) so that a digital ID issued in, say, Colorado is trusted by a bank in New York or a federal portal, just as state driver’s licenses are mutually recognized today. Done right, a digital ID saves time and protects privacy: imagine applying for benefits or a loan online by simply confirming a verified ID attribute (e.g. “I am Alice, over 18 and a U.S. citizen”) rather than scanning and emailing your driver’s license to unknown clerks.

Universal, Real-time Payments (G2P, P2G, P2P)

The DPI Act should ensure that instant payment capability becomes as ubiquitous as email. This likely means leveraging FedNow, the Federal Reserve’s new instant payment rail, and expanding its use. For Government-to-Person (G2P) payments, Congress could mandate that federal disbursements (tax refunds, Social Security, veterans’ benefits, emergency relief, etc.) use a real-time option by default, with an ACH or card fallback only if a recipient opts out.

No citizen should wait days or weeks for funds that could be sent in seconds. The same goes for Person-to-Government (P2G) payments: taxes, fees, and fines should be payable instantly online, with immediate confirmation. This reduces float and uncertainty for both citizens and agencies. Finally, Person-to-Person (P2P): while the government doesn’t run private payment apps, a robust public instant payments infrastructure can connect banks of all sizes, enabling truly universal P2P transfers. This way, someone at Bank A can instantly pay someone at Credit Union B without needing both to join the same private app.

FedNow, as a public utility, is an important player, but the Act could incentivize or require banks to join so no institution is left behind. The result would be a seamless national payments system where money moves as fast as email, enabling things like on-demand wage payments, rapid disaster aid, and easier commerce.

Cross-sector, Consent-based Data Exchange

The third pillar is perhaps the most forward-looking: creating standard protocols for data sharing that put individuals in control. Imagine a secure digital pipeline that lets you, the citizen, pull or push your personal data from one place to another with a click – for instance, authorizing the IRS to share your income info directly with a state college financial aid office, or allowing your bank to verify your identity by querying a DMV record (with your consent) instead of asking you to upload photos or scans.

A DPI Act can establish an open-data exchange framework inspired by efforts like open banking and TEFCA, but broader. This framework would include technical standards (APIs, encryption, logging of data requests) and legal rules (what consents are needed, liability for misuse, etc.) to enable “tell us once” convenience for the public.

Importantly, it must be consent-based: your data doesn’t move unless you approve and authorize it.It can let you carry digital attestations i.e. driver’s license, vaccination, veteran status, etc. on an e-wallet and share just the necessary bits with whoever needs to know. Some building blocks already exist: the federal Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) is working on health data interoperability through TEFCA (so hospitals can query each other’s records), and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has begun rulemaking to give bank customers the right to share their financial data with third-party apps.

A DPI Act could unify these efforts under one umbrella, extend them to other domains, and fill in the gaps (for instance, enabling portable eligibility, if you qualify for one program, easily prove it for another). It could establish a governance entity or standards board to oversee the trust frameworks needed. Crucially, this must be accompanied by strong privacy and security measures like audit trails, encryption, and an emphasis that individuals can see and control who accesses their data. An example of this is how the EU wallet provides a dashboard for users to review and revoke data sharing.

The Digital Public Infrastructure Act would not necessarily build each piece from scratch but set national standards and provide funding to knit them together. It could, for example, direct NIST and a multi-agency task force to implement a federated ID by a certain date (building on Login.gov’s lessons), require the Treasury and Federal Reserve to ensure every American has a route to instant payments across platforms (leveraging FedNow), and authorize pilot programs for cross-sector data exchange in key areas like social services.

Precedent for such an approach already exists in bipartisan efforts:

Navigating Roadblocks: Federalism, Privacy, and Tech Contractors

Enacting a U.S. Digital Public Infrastructure Act will face several real challenges. It’s important to acknowledge these roadblocks and consider strategies to overcome them:

Federalism and Decentralized Authority

Unlike many countries where a central government can launch a national ID or payments platform by decree, the U.S. must coordinate federal, state, and local authorities. Identity in the U.S. is traditionally a state domain (driver’s licenses, birth certificates), while federal agencies also issue identifiers (Social Security numbers, passports). A DPI solution must respect these layers. States may fear a federal takeover of their DMV role, and agencies might guard their IT turf. Solution: design the system as a federation of trust. The Act could explicitly empower states by providing grants for states to upgrade to digital driver’s licenses (the Improving Digital Identity Act proposed in 2022 did exactly this, offering grants for state DMV mobile IDs). It could also create a governance council with state CIOs and federal officials to jointly set standards.

Civil Liberties and Privacy Concerns

Any mention of a “digital ID” in America raises eyebrows about Big Brother. Civil liberties advocates will rightly question how to prevent government overreach or mass surveillance. The Act should incorporate privacy by design provisions e.g., require minimal data collection, mandate independent audits for security, and give users legal rights over their data. One promising approach is using decentralized identity technologies, where your personal data (like credentials) stay mostly on your device under your control, and only verification proofs are shared. Also, the law can explicitly forbid certain uses, for instance, prohibit law enforcement from fishing through the digital ID system without a warrant, or forbid using the digital ID for profiling citizens. Including groups like the ACLU and EFF in the drafting process could help address concerns early. It’s worth noting that privacy and security can actually be enhanced by a good digital ID: today, Americans hand over copious personal details to random companies for ID checks (e.g. scan of your driver’s license to rent an apartment, which might sit in a landlord’s email forever). A federated ID could reduce exposure by only transmitting a yes/no verification or a single attribute, rather than a photocopy of your entire ID. Conveying that narrative, that this can protect people from identity theft and data breaches, will be key to overcoming knee-jerk opposition. Still, robust safeguards and perhaps a pilot phase to prove the concept will be needed to convince skeptics that a U.S. digital identity won’t become a surveillance tool.

Incumbent Resistance (Big tech and Contractors)

There are vested interests in the current disjointed system. Large federal IT contractors and identity verification vendors profit from selling agencies one-off solutions; big tech companies dominate payments and data silos in the status quo. A unified public infrastructure could be seen as competition or a threat to some business models. For example, if a free government-backed digital ID becomes widely accepted, companies like credit bureaus (which sell ID verification services) or ID.me might lose market share. If open-data sharing is mandated, banks that monetize data might push back. The solution is to engage industry so they can find new opportunities within the ecosystem. Many banks, for instance, actually support digital ID because it would cut fraud costs for them. The banking industry has been calling for better ID verification to fight account takeover and synthetic identities. In fact, a coalition of financial institutions endorsed the earlier Improving Digital Identity legislation.

Fintechs will favor Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) because it transforms customer acquisition from a slow, expensive manual process into an instant, low-cost digital utility. By plugging into standardized government layers for identity (e-KYC) and data sharing (Account Aggregators), fintechs can instantly verify and underwrite users who lack traditional credit histories. This allows them to scale rapidly and profitably serve millions of previously “unbanked” customers by making lending decisions based on real-time data rather than rigid credit scores.. The Act can create a public-private task force (as earlier bills proposed) to hash out implementation. For government contractors, the reality is that building DPI will still require significant IT work, just more standardized. Contractors who adapt can win contracts to build the new infrastructure.

Political Will and Public Perception

DPI can be a bipartisan win if framed correctly.

For conservatives and fiscal hawks: emphasize the anti-fraud, waste-cutting angle. Stopping improper payments (recall that $236B figure!) and preventing identity theft aligns with the goal of efficient government. The Act essentially plugs leaky buckets, something everyone can get behind.

For liberals and tech-progressives: emphasize equity and empowerment. How digital infrastructure can help the unbanked access financial services, ensure eligible people aren’t left out of benefits, and give individuals control of their own data (a pro-consumer, anti-monopoly stance). Indeed, digital public goods are often framed as a way to ensure big tech doesn’t exclusively control our digital lives.

The key will be avoiding hot button mis-framings: this is not a surveillance program, not a national social credit system, etc. It’s an upgrade to basic government digital infrastructure. One strategy is to start with pilot programs and voluntary adoption to build trust. For example, the Act could fund a pilot in a few states to link a state’s digital driver’s license with federal Login.gov accounts, showing a working federated ID in action. Or pilot using FedNow for a chunk of tax refunds in one region. Early successes will create momentum and help refine the approach. Champions in the Congress will need to communicate that this is infrastructure in the truest sense: just as U.S. needed electrification and interstate highways, it now needs the digital equivalent to keep America competitive and secure.

Conclusion

A Digital Public Infrastructure Act represents more than a technical upgrade; it is an investment in America’s institutional capacity. The challenges the U.S. faces today like identity theft, improper payments, slow benefit delivery, and fragmented data governance are the predictable consequences of an outdated public digital foundation that has never been treated as national infrastructure. Just as the interstate highway system knit together the physical economy, and just as the early internet created the backbone for the digital economy, the United States now needs a unified, secure, and interoperable set of digital rails to support the next era of public service delivery and economic growth.

Unlike centralized systems elsewhere in the world, the American version of DPI would be federated, privacy-preserving, and deeply respectful of federalism. States would remain primary issuers of identity credentials. Private innovators would continue to build consumer-facing services. Federal agencies would govern standards rather than run monolithic platforms. This hybrid model plays to America’s institutional strengths such as distributed authority, competitive innovation, and strong civil liberties protections.

Congress must enact a Digital Public Infrastructure Act, a recognition that the government’s most fundamental responsibility in the digital era is to provide a solid, trustworthy foundation upon which people, businesses, and communities can build. America has done this before when it built the railroads, electrified the nation, and invested in the early internet. The next great public works project must be digital.

This rule gives agencies significantly more authority over certain career policy roles. Whether that authority improves accountability or creates new risks depends almost entirely on how agencies interrupt and apply it.

Our environmental system was built for 1970s-era pollution control, but today it needs stable, integrated, multi-level governance that can make tradeoffs, share and use evidence, and deliver infrastructure while demonstrating that improved trust and participation are essential to future progress.

Durable and legitimate climate action requires a government capable of clearly weighting, explaining, and managing cost tradeoffs to the widest away of audiences, which in turn requires strong technocratic competency.

The American administrative state, since its modern creation out of the New Deal and the post-WWII order, has proven that it can do great things. But it needs some reinvention first.