Nuclear Notebook: French Nuclear Weapons, 2023

The FAS Nuclear Notebook is one of the most widely sourced reference materials worldwide for reliable information about the status of nuclear weapons and has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: Director Hans M. Kristensen, Senior Research Fellow Matt Korda, and Research Associate Eliana Johns.

This issue’s column reviews the status of France’s nuclear arsenal and finds that the stockpile of approximately 290 warheads has remained stable in recent years. However, significant modernizations regarding ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, submarines, aircraft, and the nuclear industrial complex are underway.

Read the full “French Nuclear Weapons, 2023” Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, or download a PDF using the button on the left side of this page. The complete archive of FAS Nuclear Notebooks can be found here.

Applying ARPA-I: A Proven Model for Transportation Infrastructure

Executive Summary

In November 2021, Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which included $550 billion in new funding for dozens of new programs across the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT). Alongside historic investments in America’s roads and bridges, the bill created the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure (ARPA-I). Building on successful models like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Advanced Research Program-Energy (ARPA-E), ARPA-I’s mission is to bring the nation’s most innovative technology solutions to bear on our most significant transportation infrastructure challenges.

ARPA-I must navigate America’s uniquely complex infrastructure landscape, characterized by limited federal research and development funding compared to other sectors, public sector ownership and stewardship, and highly fragmented and often overlapping ownership structures that include cities, counties, states, federal agencies, the private sector, and quasi-public agencies. Moreover, the new agency needs to integrate the strong culture, structures, and rigorous ideation process that ARPAs across government have honed since the 1950s. This report is a primer on how ARPA-I, and its stakeholders, can leverage this unique opportunity to drive real, sustainable, and lasting change in America’s transportation infrastructure.

How to Use This Report

This report highlights the opportunity ARPA-I presents; orients those unfamiliar with the transportation infrastructure sector to the unique challenges it faces; provides a foundational understanding of the ARPA model and its early-stage program design; and empowers experts and stakeholders to get involved in program ideation. However, individual sections can be used as standalone tools depending on the reader’s prior knowledge of and intended involvement with ARPA-I.

- If you are unfamiliar with the background, authorization, and mission of ARPA-I, refer to the section “An Opportunity for Transportation Infrastructure Innovation.”

- If you are relatively new to the transportation infrastructure sector, refer to the section “Unique Challenges of the Transportation Infrastructure Landscape.”

- If you have prior transportation infrastructure experience or expertise but are new to the ARPA model, you can move directly to the sections beginning with “Core Tenets of ARPA Success.”

An Opportunity for Transportation Infrastructure Innovation

In November 2021, Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) authorizing the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) to create the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure (ARPA-I), among other new programs. ARPA-I’s mission is to advance U.S. transportation infrastructure by developing innovative science and technology solutions that:

- lower the long-term cost of infrastructure development, including costs of planning, construction, and maintenance;

- reduce the life cycle impacts of transportation infrastructure on the environment, including through the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions;

- contribute significantly to improving the safe, secure, and efficient movement of goods and people; and

- promote the resilience of infrastructure from physical and cyber threats.

ARPA-I will achieve this goal by supporting research projects that:

- advance novel, early-stage research with practicable application to transportation infrastructure;

- translate techniques, processes, and technologies, from the conceptual phase to prototype, testing, or demonstration;

- develop advanced manufacturing processes and technologies for the domestic manufacturing of novel transportation-related technologies; and

- accelerate transformational technological advances in areas in which industry entities are unlikely to carry out projects due to technical and financial uncertainty.

ARPA-I is the newest addition to a long line of successful ARPAs that continue to deliver breakthrough innovations across the defense, intelligence, energy, and health sectors. The U.S. Department of Defense established the pioneering Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in 1958 in response to the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite to develop and demonstrate high-risk, high-reward technologies and capabilities to ensure U.S. military technological superiority and confront national security challenges. Throughout the years, DARPA programs have been responsible for significant technological advances with implications beyond defense and national security, such as the early stages of the internet, the creation of the global positioning system (GPS), and the development of mRNA vaccines critical to combating COVID-19.

In light of the many successful advancements seeded through DARPA programs, the government replicated the ARPA model for other critical sectors, resulting in the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy within the Department of Energy, and, most recently, the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Health (ARPA-H) within the Department of Health and Human Services.

Now, there is the opportunity to bring that same spirit of untethered innovation to solve the most pressing transportation infrastructure challenges of our time. The United States has long faced a variety of transportation infrastructure-related challenges, due in part to low levels of federal research and development (R&D) spending in this area; the fragmentation of roles across federal, state, and local government; risk-averse procurement practices; and sluggish commercial markets. These challenges include:

- Roadway safety. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, an estimated 42,915 people died in motor vehicle crashes in 2021, up 10.5% from 2020.

- Transportation emissions. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the transportation sector accounted for 27% of U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020, more than any other sector.

- Aging infrastructure and maintenance. According to the 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure produced by the American Society of Civil Engineers, 42% of the nation’s bridges are at least 50 years old and 7.5% are “structurally deficient.”

The Fiscal Year 2023 Omnibus Appropriations Bill awarded ARPA-I its initial appropriation in early 2023. Yet even before that, the Biden-Harris Administration saw the potential for ARPA-I-driven innovations to help meet its goal of net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, as articulated in its Net-Zero Game Changers Initiative. In particular, the Administration identified smart mobility, clean and efficient transportation systems, next-generation infrastructure construction, advanced electricity infrastructure, and clean fuel infrastructure as “net-zero game changers” that ARPA-I could play an outsize role in helping develop.

For ARPA-I programs to reach their full potential, agency stakeholders and partners need to understand not only how to effectively apply the ARPA model but how the unique circumstances and challenges within transportation infrastructure need to be considered in program design.

Unique Challenges of the Transportation Infrastructure Landscape

Using ARPA-I to advance transportation infrastructure breakthroughs requires an awareness of the most persistent challenges to prioritize and the unique set of circumstances within the sector that can hinder progress if ignored. Below are summaries of key challenges and considerations for ARPA-I to account for, followed by a deeper analysis of each challenge.

- Federal R&D spending on transportation infrastructure is considerably lower than other sectors, such as defense, healthcare, and energy, as evidenced by federal spending as a percentage of that sector’s contribution to gross domestic product (GDP).

- The transportation sector sees significant private R&D investment in vehicle and aircraft equipment but minimal investment in transportation infrastructure because the benefits from those investments are largely public rather than private.

- Market fragmentation within the transportation system is a persistent obstacle to progress, resulting in reliance on commercially available technologies and transportation agencies playing a more passive role in innovative technology development.

- The fragmented market and multimodal nature of the sector pose challenges for allocating R&D investments and identifying customers.

Lower Federal R&D Spending in Transportation Infrastructure

Federal R&D expenditures in transportation infrastructure lag behind those in other sectors. This gap is particularly acute because, unlike for some other sectors, federal transportation R&D expenditures often fund studies and systems used to make regulatory decisions rather than technological innovation. The table below compares actual federal R&D spending and sector expenditures for 2019 across defense, healthcare, energy, and transportation as a percentage of each sector’s GDP. The federal government spends orders of magnitude less on transportation than other sectors: energy R&D spending as a percentage of sector GDP is nearly 15 times higher than transportation, while health is 13 times higher and defense is nearly 38 times higher.

Public Sector Dominance Limits Innovation Investment

Since 1990, total investment in U.S. R&D has increased by roughly 9 times. When looking at the source of R&D investment over the same period, the private and public sectors invested approximately the same amount of R&D funding in 1982, but today the rate of R&D investment is nearly 4 times greater for the private industry than the government.

While there are problems with the bulk of R&D coming from the private sector, such as innovations to promote long-term public goods being overlooked because of more lucrative market incentives, industries that receive considerable private R&D funding still see significant innovation breakthroughs. For example, the medical industry saw $161.8 billion in private R&D funding in 2020 compared to only $61.5 billion from federal funding. More than 75% of this private industry R&D occurred within the biopharmaceutical sector where corporations have profit incentives to be at the cutting edge of advancements in medicine.

The transportation sector has one robust domain for private R&D investment: vehicle and aircraft equipment manufacturing. In 2018, total private R&D was $52.6 billion. Private sector transportation R&D focuses on individual customers and end users, creating better vehicles, products, and efficiencies. The vast majority of that private sector R&D does not go toward infrastructure because the benefits are largely public rather than private. Put another way, the United States invests more than 50 times the amount of R&D into vehicles than the infrastructure systems upon which those vehicles operate.

Market Fragmentation across Levels of Government

Despite opportunities within the public-dominated transportation infrastructure system, market fragmentation is a persistent obstacle to rapid progress. Each level of government has different actors with different objectives and responsibilities. For instance, at the federal level, USDOT provides national-level guidance, policy, and funding for transportation across aviation, highway, rail, transit, ports, and maritime modes. Meanwhile, the states set goals, develop transportation plans and projects, and manage transportation networks like the interstate highway system. Metropolitan planning organizations take on some of the planning functions at the regional level, and local governments often maintain much of their infrastructure. There are also local individual agencies that operate facilities like airports, ports, or tollways organized at the state, regional, or local level. Programs that can use partnerships to cut across this tapestry of systems are essential to driving impact at scale.

Local agencies have limited access and capabilities to develop cross-sector technologies. They have access to limited pools of USDOT funding to pilot technologies and thus generally rely on commercially available technologies to increase the likelihood of pilot success. One shortcoming of this current process is that both USDOT and infrastructure owner-operators (IOOs) play a more passive role in developing innovative technologies, instead depending on merely deploying market-ready technologies.

Multiple Modes, Customers, and Jurisdictions Create Difficulties in Efficiently Allocating R&D Resources

The transportation infrastructure sector is a multimodal environment split across many modes, including aviation, maritime, pipelines, railroads, roadways (which includes biking and walking), and transit. Each mode includes various customers and stakeholders to be considered. In addition, in the fragmented market landscape federal, state, and local departments of transportation have different—and sometimes competing—priorities and mandates. This dynamic creates difficulties in allocating R&D resources and considering access to innovation across these different modes.

Customer identification is not “one size fits all” across existing ARPAs. For example, DARPA has a laser focus on delivering efficient innovations for one customer: the Department of Defense. For ARPA-E, it is less clear; their customers range from utility companies to homeowners looking to benefit from lower energy costs. ARPA-I would occupy a space in between these two cases, understanding that its end users are IOOs—entities responsible for deploying infrastructure in many cases at the local or regional level.

However, even with this more direct understanding of its customers, a shortcoming of a system focused on multiple modes is that transportation infrastructure is very broad, occupying everything from self-healing concrete to intersection safety to the deployment of electrified mobility and more. Further complicating matters is the rapid evolution of technologies and expectations across all modes, along with the rollout of entirely new modes of transportation. These developments raise questions about where new technologies and capabilities fit in existing modal frameworks, what actors in the transportation infrastructure market should lead their development, and who the ultimate “customers” or end users of innovation are.

Having a matrixed understanding of the rapid technological evolution across transportation modes and their potential customers is critical to investing in and building infrastructure for the future, given that transportation infrastructure investments not only alter a region’s movement of people and goods but also fundamentally impact its development. ARPA-I is poised to shape learnings across and in partnership with USDOT’s modes and various offices to ensure the development and refinement of underlying technologies and approaches that serve the needs of the entire transportation system and users across all modes.

Core Tenets of ARPA Success

Success using the ARPA model comes from demonstrating new innovative capabilities, building a community of people (an “ecosystem”) to carry the progress forward, and having the support of key decision-makers. Yet the ARPA model can only be successful if its program directors (PDs), fellows, stakeholders, and other partners understand the unique structure and inherent flexibility required when working to create a culture conducive to spurring breakthrough innovations. From a structural and cultural standpoint, the ARPA model is unlike any other agency model within the federal government, including all existing R&D agencies. Partners and other stakeholders should embrace the unique characteristics of an ARPA.

Cultural Components

ARPAs should take risks.

An ARPA portfolio may be the closest thing to a venture capital portfolio in the federal government. They have a mandate to take big swings so should not be limited to projects that seem like safe bets. ARPAs will take on many projects throughout their existence, so they should balance quick wins with longer-term bets while embracing failure as a natural part of the process.

ARPAs should constantly evaluate and pivot when necessary.

An ARPA needs to be ruthless in its decision-making process because it has the ability to maneuver and shift without the restriction of initial plans or roadmaps. For example, projects around more nascent technology may require more patience, but if assessments indicate they are not achieving intended outcomes or milestones, PDs should not be afraid to terminate those projects and focus on other new ideas.

ARPAs should stay above the political fray.

ARPAs can consider new and nontraditional ways to fund innovation, and thus should not be caught up in trends within their broader agency. As different administrations onboard, new offices get built and partisan priorities may shift, but ARPAs should limit external influence on their day-to-day operations.

ARPA team members should embrace an entrepreneurial mindset.

PDs, partners, and other team members need to embrace the creative freedom required for success and operate much like entrepreneurs for their programs. Valued traits include a propensity toward action, flexibility, visionary leadership, self-motivation, and tenacity.

ARPA team members must move quickly and nimbly.

Trying to plan out the agency’s path for the next two years, five years, 10 years, or beyond is a futile effort and can be detrimental to progress. ARPAs require ultimate flexibility from day to day and year to year. Compared to other federal initiatives, ARPAs are far less bureaucratic by design, and forcing unnecessary planning and bureaucracy on the agency will slow progress.

Collegiality must be woven into the agency’s fabric.

With the rapidly shifting and entrepreneurial nature of ARPA work, the federal staff, contractors, and other agency partners need to rely on one another for support and assistance to seize opportunities and continue progressing as programs mature and shift.

Outcomes matter more than following a process.

ARPA PDs must be free to explore potential program and project ideas without any predetermination. The agency should support them in pursuing big and unconventional ideas unrestricted by a particular process. While there is a process to turn their most unconventional and groundbreaking ideas into funded and functional projects, transformational ideas are more important than the process itself during idea generation.

ARPA team members welcome feedback.

Things move quickly in an ARPA, and decisions must match that pace, so individuals such as fellows and PDs must work together to offer as much feedback as possible. Constructive pushback helps avoid blind alleys and thus makes programs stronger.

Structural Components

The ARPA Director sets the vision.

The Director’s vision helps attract the right talent and appropriate levels of ambition and focus areas while garnering support from key decision-makers and luminaries. This vision will dictate the types and qualities of PDs an ARPA will attract to execute within that vision.

PDs can make or break an ARPA and set the technical direction.

Because the power of the agency lies within its people, ARPAs are typically flat organizations. An ARPA should seek to hire the best and most visionary thinkers and builders as PDs, enable them to determine and design good programs, and execute with limited hierarchical disruption. During this process, PDs should engage with decision-makers in the early stages of the program design to understand the needs and realities of implementers.

Contracting helps achieve goals.

The ARPA model allows PDs to connect with universities, companies, nonprofits, organizations, and other areas of government to contract necessary R&D. This allows the program to build relationships with individuals without needing to hire or provide facilities or research laboratories.

Interactions improve outcomes.

From past versions of ARPA that attempted remote and hybrid environments, it became evident that having organic collisions across an ARPA’s various roles and programs is important to achieving better outcomes. For example, ongoing in-person interactions between and among PDs and technical advisors are critical to idea generation and technical project and program management.

Staff transitions must be well facilitated to retain institutional knowledge.

One of ARPA’s most unique structural characteristics is its frequent turnover. PDs and fellows are term-limited, and ARPAs are designed to turn over those key positions every few years as markets and industries evolve, so having thoughtful transition processes in place is vital, including considering the role of systems engineering and technical assistance (SETA) contractors in filling knowledge gaps, cultivating an active alumni network, and staggered hiring cycles so that large numbers of PDs and fellows are not all exiting their service at once.

Scaling should be built into the structure.

It cannot be assumed that if a project is successful, the private sector will pick that technology up and help it scale. Instead, an ARPA should create its own bridge to scaling in the form of programs dedicated to funding projects proven in a test environment to scale their technology for real-world application.

Technology-to-market advisors play a pivotal role.

Similarly to the dedicated funding for scaling described above, technology-to-market advisors are responsible for thinking about how projects make it to the real world. They should work hand in hand with PDs even in the early stages of program development to provide perspectives on how projects might commercialize and become market-ready. Without this focus, technologies run the risk of dying on the vine—succeeding technically, but failing commercially.

A Primer on ARPA Ideation

Tackling grand challenges in transportation infrastructure through ARPA-I requires understanding what is unique about its program design. This process begins with considering the problem worth solving, the opportunity that makes it a ripe problem to solve, a high-level idea of an ARPA program’s fit in solving it, and a visualization of the future once this problem has been solved. This process of early-stage program ideation requires a shift in one’s thinking to find ideas for innovative programs that fit the ARPA model in terms of appropriate ambition level and suitability for ARPA structure and objectives. It is also an inherently iterative process, so while creating a “wireframe” outlining the problem, opportunity, program objectives, and future vision may seem straightforward, it can take months of refining.

Common Challenges

No clear diagnosis of the problem

Many challenges facing our transportation infrastructure system are not defined by a single problem; rather, they are a conglomeration of issues that simultaneously need addressing. An effective program will not only isolate a single problem to tackle, but it will approach it at a level where something can be done to solve it through root cause analysis.

Thinking small and narrow

On the other hand, problems being considered for ARPA programs can be isolated down to the point that solving them will not drive transformational change. In this situation, narrow problems would not cater to a series of progressive and complementary projects that would fit an ARPA.

Incorrect framing of opportunities:

When doing early-stage program design, opportunities are sometimes framed as “an opportunity to tackle a problem.” Rather, an opportunity should reflect a promising method, technology, or approach already in existence but which would benefit from funding and resources through an advanced research agency program.

Approaching solutions solely from a regulatory or policy angle

While regulations and policy changes are a necessary and important component of tackling challenges in transportation infrastructure, approaching issues through this lens is not the mandate of an ARPA. ARPAs focus on supporting breakthrough innovations in developing new methods, technologies, capabilities, and approaches. Additionally, regulatory approaches to problem-solving can often be subject to lengthy policy processes.

No explicit ARPA role

An ARPA should pursue opportunities to solve problems where, without its intervention, breakthroughs may not happen within a reasonable timeframe. If the public or private sector already has significant interest in solving a problem, and they are well on their way to developing a transformational solution in a few years or less, then ARPA funding and support might provide a higher value-add elsewhere.

Lack of throughline

The problems identified for ARPA program consideration should be present as themes throughout the opportunities chosen to solve them as well as how programs are ultimately structured. Otherwise, a program may lack a targeted approach to solving a particular challenge.

Forgetting about end users

Human-centered design should be at the heart of how ARPA programs are scoped, especially when considering the scale at which designers need to think about how solving a problem will provide transformational change for everyday users.

Being solutions-oriented

Research programs should not be built with predetermined solutions in mind; they should be oriented around a specific problem to ensure that any solutions put forward are targeted and effective.

Not being realistic about direct outcomes of the program

Program objectives should not simply restate the opportunity, nor should they jump to where the world will be many years after the program has run its course. They should separate the tactical elements of a program and what impact they will ultimately drive. Designers should consider their program as one key step in a long arc of commercialization and adoption, with a firm sense of who needs to act and what needs to happen to make a program objective a reality.

Keeping these common mistakes in mind throughout the design process ensures that programs are properly scoped, appropriately ambitious, and in line with the agency’s goals. With these guideposts in mind, idea generators should begin their program design in the form of a wireframe.

Wireframe Development

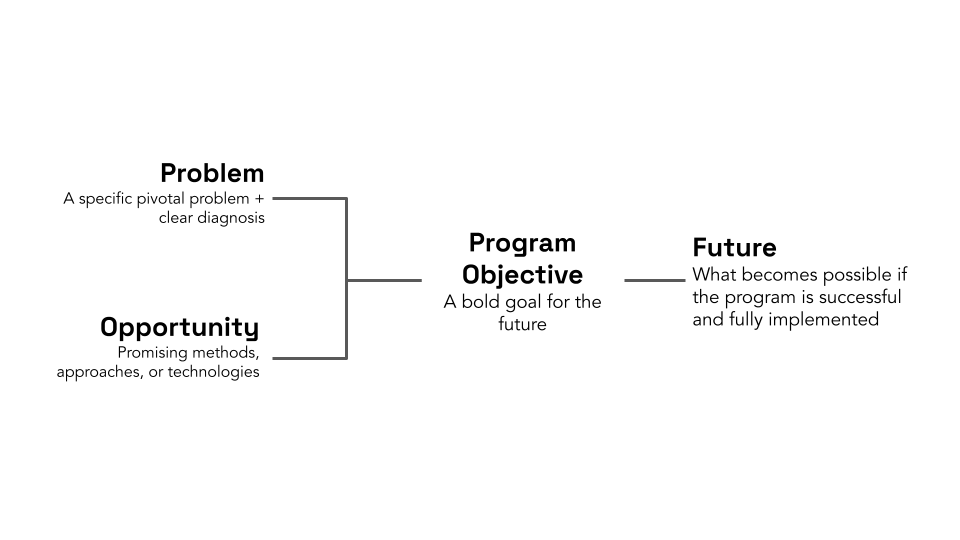

The first phase in ARPA program development is creating a program wireframe, which is an outline of a potential program that captures key components for consideration to assess the program’s fit and potential impact. The template below shows the components characteristic of a program wireframe.

To create a fully fleshed-out wireframe, program directors work backward by first envisioning a future state that would be truly transformational for society and across sectors if it were to be realized. Then, they identify a clearly-articulated problem that needs solving and is hindering progress toward this transformational future state. During this process, PDs need to conduct extensive root cause analysis to consider whether the problem they’ve identified is exacerbated by policy, regulatory, or environmental complications—as opposed to those that technology can already solve. This will inform whether a problem is something that ARPA-I has the opportunity to impact fundamentally.

Next, program directors identify a promising opportunity—such as a method, approach, or technology—that, if developed, scaled, and implemented, would solve the problem they articulated and help achieve their proposed future state. When considering a promising opportunity, PDs must assess whether it front-runs other potential technologies that would also need developing to support it and whether it is feasible to achieve concrete results within three to five years and with an average program budget. Additionally, it is useful to think about whether an opportunity considered for program development is part of a larger cohort of potential programs that lie within an ARPA-I focus area that could all be run in parallel.

Most importantly, before diving into how to solve the problem, PDs need to articulate what has prevented this opportunity from already being solved, scaled, and implemented, and what explicit role or need there is for a federal R&D agency to step in and lead the development of technologies, methods, or approaches to incentivize private sector deployment and scaling. For example, if the private sector is already incentivized to, and capable of, taking the lead on developing a particular technology and it will achieve market readiness within a few years, then there is less justification for an ARPA intervention in that particular case. On the other hand, the prescribed solution to the identified problem may be so nascent that what is needed is more early-stage foundational R&D, in which case an ARPA program would not be a good fit. This area should be reserved as the domain of more fundamental science-based federal R&D agencies and offices.

One example to illustrate this maturity fit is DARPA investment in mRNA. While the National Institutes of Health contributed significantly to initial basic research, DARPA recognized the technological gap in being able to quickly scale and manufacture therapeutics, prompting the agency to launch the Autonomous Diagnostics to Enable Prevention and Therapeutics (ADEPT) program to develop technologies to respond to infectious disease threats. Through ADEPT, in 2011 DARPA awarded a fledgling Moderna Therapeutics with $25 million to research and develop its messenger RNA therapeutics platform. Nine years later, Moderna became the second company after Pfizer-BioNTech to receive an Emergency Use Authorization for its COVID-19 vaccine.

Another example is DARPA’s role in developing the internet as we know it, which was not originally about realizing the unprecedented concept of a ubiquitous, global communications network. What began as researching technologies for interlinking packet networks led to the development of ARPANET, a pioneering network for sharing information among geographically separated computers. DARPA then contracted BBN Technologies to build the first routers before becoming operational in 1969. This research laid the foundation for the internet. The commercial sector has since adopted ARPANET’s groundbreaking results and used them to revolutionize communication and information sharing across the globe.

Wireframe Refinement and Iteration

To guide program directors through successful program development, George H. Heilmeier, who served as the director of DARPA from 1975 to 1977, used to require that all PDs answer the following questions, known as the Heilmeier Catechism, as part of their pitch for a new program. These questions should be used to refine the wireframe and envision what the program could look like. In particular, wireframe refinement should examine the first three questions before expanding to the remaining questions.

- What are you trying to do? Articulate your objectives using absolutely no jargon.

- How is it done today, and what are the limits of current practice?

- What is new in your approach, and why do you think it will be successful?

- Who cares? If you are successful, what difference will it make?

- What are the risks?

- How much will it cost?

- How long will it take?

- What are the midterm and final “exams” to check for success?

Alongside the Heilmeier Catechism, a series of assessments and lines of questioning should be completed to pressure test and iterate once the wireframe has been drafted. This refinement process is not one-size-fits-all but consistently grounded in research, discussions with experts, and constant questioning to ensure program fit. The objective is to thoroughly analyze whether the problem we are seeking to solve is the right one and whether the full space of opportunities around that problem is ripe for ARPA intervention.

One way to think about determining whether a wireframe could be a program is by asking, “Is this wireframe science or is this science fiction?” In other words, is the proposed technology solution at the right maturity level for an ARPA to make it a reality? There is a relatively broad range in the middle of the technological maturity spectrum that could be an ARPA program fit, but the extreme ends of that spectrum would not be a good fit, and thus those wireframes would need further iteration or rejection. On the far left end of the spectrum would be basic research that only yields published papers or possibly a prototype. On the other extreme would be a technology that is already developed to the point that only full-scale implementation is needed. Everything that falls between could be suitable for an ARPA program topic area.

Once a high-impact program has been designed, the next step is to rigorously pressure test and develop a program until it resembles an executable ARPA program.

Applying ARPA Frameworks to Transportation Infrastructure Challenges

By using this framework, any problem or opportunity within transportation infrastructure can be evaluated for its fit as an ARPA-level idea. Expert and stakeholder idea generation is essential to creating an effective portfolio of ARPA-I programs, so idea generators must be armed with this framework and a defined set of focus areas to develop promising program wireframes. An initial set of focus areas for ARPA-I includes safety, climate and resilience, and digitalization, with equity and accessibility as underlying considerations within each focus area.

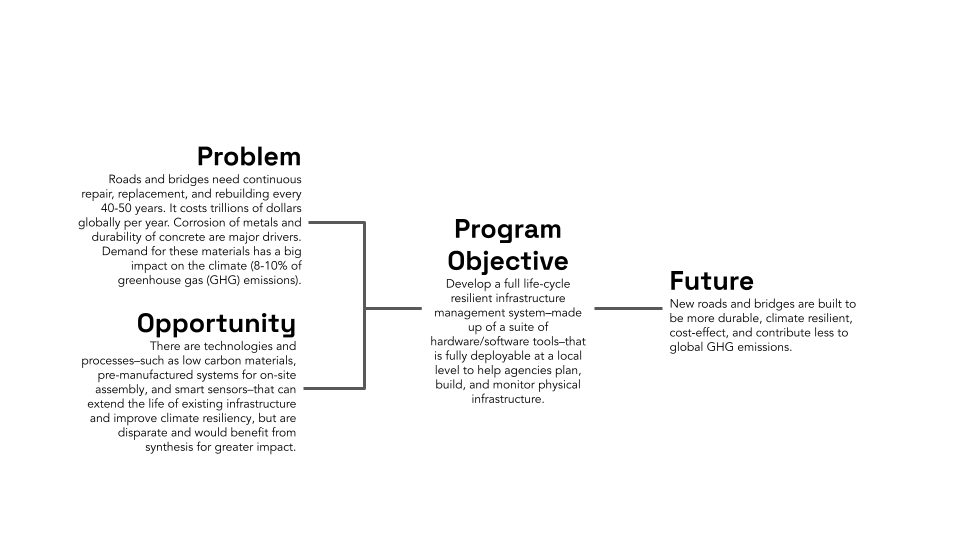

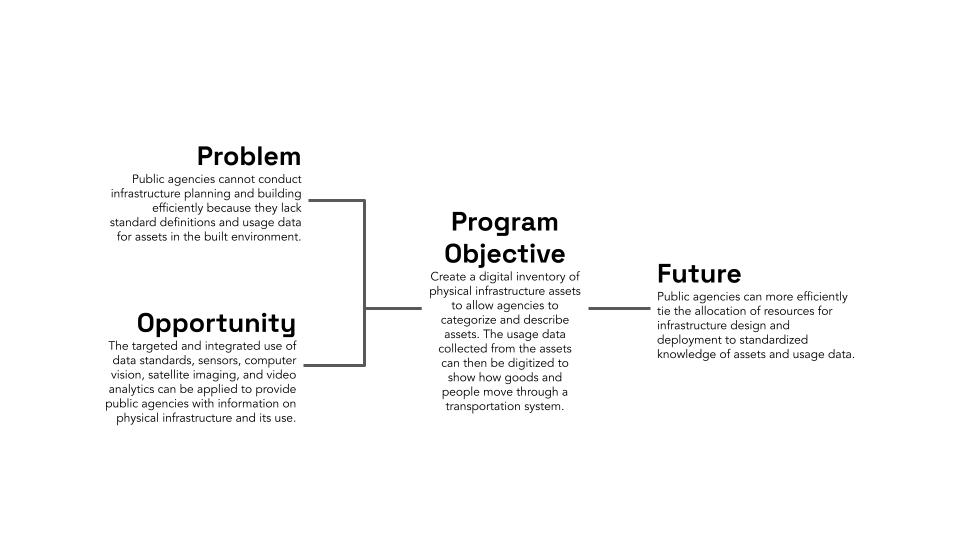

There are hundreds of potential topic areas that ARPA-I could tackle; the two wireframes below represent examples of early-stage program ideas that would benefit from further pressure testing through the program design iteration cycle.

Note: The following wireframes are samples intended to illustrate ARPA ideation and the wireframing process, and do not represent potential research programs or topics under consideration by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Next-Generation Resilient Infrastructure Management

A Digital Inventory of Physical Infrastructure and Its Uses

Wireframe Development Next Steps

After initial wireframe development, further exploration is needed to pressure test an idea and ensure that it can be developed into a viable program to achieve “moonshot” ambitions. Wireframe authors should consider the following factors when iterating:

- The Heilmeier Catechism questions (see page 14) and whether the wireframe needs to be updated or revised as they seek to answer each of the Heilmeier Catechism questions

- Common challenges wireframes face (see page 11) and whether any of them might be reflected in the wireframe

- The federal, state, and local regulatory landscape and any regulatory factors that will impact the direction of a potential research program

- Whether the problem or technology already receives significant investment from other sources (if there is significant investment from venture capital, private equity, or elsewhere, then it would not be an area of interest for ARPA-I)

- Adjacent areas of work that might inform or affect a potential research program

- The transportation infrastructure sector’s unique challenges and landscape

- How long will it take?

- Existing grant programs and opportunities that might achieve similar goals

Wireframes are intended to be a summary communicative of a larger plan to follow. After further iteration and exploration of the factors outlined above, what was first just a raw program wireframe should develop into more detailed documents. These should include an incisive diagnosis of the problem and evidence and citations validating opportunities to solve it. Together, these components should lead to a plausible program objective as an outcome.

Conclusion

The newly authorized and appropriated ARPA-I presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to apply a model that has been proven successful in developing breakthrough innovations in other sectors to the persistent challenges facing transportation infrastructure.

Individuals and organizations that would work within the ARPA-I network need to have a clear understanding of the unique circumstances, challenges, and opportunities of this sector, as well as how to apply this context and the unique ARPA program ideation model to build high-impact future innovation programs. This community’s engagement is critical to ARPA-I’s success, and the FAS is looking for big thinkers who are willing to take on this challenge by developing bold, innovative ideas.

To sign up for future updates on events, convenings, and other opportunities for you to work in support of ARPA-I programs and partners, click here.

To submit an advanced research program idea, click here.

Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2023

The FAS Nuclear Notebook is one of the most widely sourced reference materials worldwide for reliable information about the status of nuclear weapons, and has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: Director Hans M. Kristensen, Senior Research Associate and Project Manager Matt Korda, and Research Associate Eliana Johns.

This issue’s column examines Russia’s nuclear arsenal, which includes a stockpile of approximately 4,489 warheads. Of these, some 1,674 strategic warheads are deployed on ballistic missiles and at heavy bomber bases, while an approximate additional 999 strategic warheads, along with 1,816 nonstrategic warheads, are held in reserve. The Russian arsenal continues its broad modernization intended to replace most Soviet-era weapons by the late-2020s.

Read the full “Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2023” Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, or download a PDF using the button on the left side of this page. The complete archive of FAS Nuclear Notebooks can be found here.

Wildland Fire Policy Recommendations

Fire is a natural and normal ecological process, but today’s fires have grown in intensity and cost, causing more destruction to people and property. A changing climate and our outdated policy responses are amplifying these negative effects.

The federal government has many responsibilities for wildland fire management in the United States. Federal entities manage public lands where prescribed burns and wildfires occur, support wildfire response, and conduct research into fire’s impacts. Recognizing that this work will only grow, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law authorized the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission to develop and deliver a comprehensive set of new policy recommendations to Congress focused on how to “better prevent, manage, suppress, and recover from wildfires.”

About the Wildland Fire Policy Accelerator

In response to the Commission’s call for input, the Federation of American Scientists launched a Wildland Fire Policy Accelerator to source and develop actionable policy ideas aimed at improving how we live with fire. This effort is in partnership with COMPASS, the California Council on Science and Technology (CCST), and Conservation X Labs, who bring deep expertise in the accelerator topics and connections to interested communities.

Participants come from academia, the private sector, nonprofits, and national labs, and bring expertise across fire ecology, forestry, modeling, climate change, fire intelligence, cultural burning, and more. The Accelerator followed the approach of the FAS Day One Project to provide structured training, support, and policy expert feedback over several months to help participants refine their policy ideas. In the Accelerator’s second phase, a subset of these contributors will publish full memos on FAS’s website with more information about their policy recommendations.

Table of Contents

Landscapes and Communities

Create Federal Indemnity Fund to cover accidental damages from cultural and prescribed fire

Chris Adlam, PhD, Oregon State University

For millennia, the forests of the West were fundamentally shaped by Tribal use of fire, with different Tribes employing unique cultural fire traditions. Unfortunately, Indigenous Cultural Fire Practitioners are now dissuaded from treating both private and public forests with cultural burns because they fear being held liable for the cost of damages in the rare cases in which cultural fires accidentally escape their planned bounds. To allow Cultural Fire Practitioners to work to restore our forests, the federal government must protect them from being held personally liable for the risks of the public service that they are performing. Similar programs are being proposed for prescribed fire; cultural burning should be equally protected and benefited by any Fund that is created.

Congress should establish and fund a Federal Cultural and Prescribed Burning Indemnity Fund to encourage wildfire prevention initiatives and to protect both fire practitioners and landowners from losses incurred from responsibly conducted cultural or prescribed burns that spread beyond their intended range.

Prescribed and cultural burning, in tandem with other treatments, are needed to reduce fuel loads and restore the health of forests that are relied upon for recreation, industry, and drinking water. Fuel treatment is also essential to reducing the cost of catastrophic wildfires, which cost the United States an estimated $14.5 billion dollars in damages and emergency response efforts from 2021 to 2022.

Across the country, prescribed burns have empirically been overwhelmingly safe. According to Chief Randy Moore of the US Forest Service, over 99.84% of prescribed fires on USFS land occur as planned. In a separate review of prescribed burns in the Southern Great Plains, researchers found similar findings that less than 1% of prescribed burns escape. Similar studies have not been conducted to analyze the empirical safety cultural burns, but surveys of relevant research did not uncover an example of an escaped cultural burn. However, the fact that risk cannot be completely eliminated weighs on practitioners and decision-makers, restricting their use of controlled burning. In the event that damages result from a burn, the Fund would seek to minimize the disruption caused by these damages by ensuring that all affected parties would be quickly and fully compensated. By creating this funding structure, landowners would no longer be dependent on individual acts of Congress to receive compensation, as victims of the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire did.

In the past year, states have begun to create similar funds after observing the need to support fire practitioners. California recently created the Prescribed Fire Claims Fund and funded it with $20 million. However, a federal fund is needed to provide coverage on a larger scale, with a scope and financial scale that is not possible for individual states.

Recommendations

To ensure that Cultural Fire Practitioners across the nation are covered, Congress should consider the following actions:

- Establish a Federal Cultural and Prescribed Burning Indemnity Fund within a federal agency (such as FEMA, which also administers Fire Prevention and Safety (FP&S) Grants) to protect both fire practitioners and landowners from losses incurred from responsibly conducted cultural or prescribed burns that spread beyond their intended range.

- Appropriate funds annually to be administered by the designated federal agency, such as FEMA. Each year, remaining funds could be rolled over to the following year or disbursed as grants to fund further cultural and prescribed burns.

- Direct FEMA (or other designated agency, as appropriate) to create a baseline gross negligence standard for cultural burns and for prescribed burns that will be used to determine the validity of claims. To gain access to the Fund, states would need liability standards that protect Fire Practitioners at a level that meets the minimum requirements outlined by the federal baseline gross negligence standards. The Fund would cover claims caused by escaped cultural fires and prescribed fires that were planned and implemented with due diligence, and the burner would cover claims that result from gross negligence by the burner.

- Direct FEMA (or other designated agency, as appropriate) to work with Tribal Nations and organizations to develop eligibility criteria that ensure that Cultural Fire Practitioners, as defined by federal definitions, are always covered by the Fund, regardless of the laws of the state in which they are operating.

- Direct administering agencies to ensure that Tribal Nations and organizations lead and oversee the administration of the Fund.

We recommend that Congress consider FEMA as the primary administrator of the Fund because it administers Fire Prevention and Safety (FP&S) Grants, which are part of the Assistance to Firefighters Grants (AFG) program, and because of its post-fire disaster assistance mission. The USDA Forest Service or the Department of the Interior are other potential administrators of the Fund. To encourage state investment, the Fund could require matching funds from states after a certain amount.

The Fund could be paired with the development of regionally specific definitions of ‘Cultural Fire Practitioner.’ These definitions of Cultural Fire Practitioners should be developed in processes led by Tribal Nations and organizations. Care should also be taken to ensure that Cultural Fire Practitioners can access the Fund without being subject to undue requirements while burning – requirements that detract from their cultural traditions or add an unmanageable regulatory burden to their work.

To further protect Cultural Fire Practitioners as they carry out vital public services, Congress could also provide Cultural Fire Practitioners with coverage under the Federal Torts Claims Act, similarly to how Tribal contractors, employees, and volunteers are classified as federal employees for the purpose of FTCA coverage. In the past, Tribal medical or law enforcement personnel have received coverage after taking over programs previously administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or the Bureau of Indian Affairs. As policy reforms allow Tribal Cultural Fire Practitioners to practice cultural burns with less interference from the BIA, FTCA coverage would become increasingly beneficial and necessary.

By creating this Fund, Congress would support fire practitioners working on the frontlines of the crisis and the communities most threatened by fire.

Directly fund Tribes to create and implement land stewardship initiatives

Nina Fontana, PhD, University of California, Davis

Across the United States, Tribal nations and organizations have the knowledge and will to lead cultural and prescribed burns. Unfortunately, they are consistently limited by (a) insufficient funds, and (b) burdensome regulatory requirements that often prove overly burdensome to comply with. These two issues are connected. Tribal practitioners are often unable to obtain federal grants for land stewardship purposes because they do not have the capacity to find and apply for them, to compete with state agencies and organizations in the application process, and to comply with the grant requirements, which can conflict with Cultural Fire traditions in fundamental ways.

Congress should appropriate discretionary funds directly to Tribal nations and Tribally-led organizations for fire hazard reduction in order to decrease the administrative capacity needed for Tribes to compete for grants. The funds will be dispersed by regional Tribal liaisons, who will gather and utilize input from local actors to direct grants.

Tribal governments and organizations require direct grant funding to exercise their sovereignty in a rightfully unencumbered manner. When Tribal governments and organizations are provided with adequate funding and are able to direct its usage, Cultural Fire Practitioners (CFPs) are able to design cultural fire projects that fit their unique traditions and local plant communities contained within their lands. In addition, by giving Tribes greater discretion over funds, the federal government would a) decrease the regulatory burden on Tribes, and b) provide greater recognition of cultural burning as a uniquely valuable form of land restoration and place-based knowledge, instead of categorizing the practice as an often-overlooked subset of prescribed burning.

Most importantly, direct funding would allow Tribal governments and organizations to shift crucial capacity away from time-intensive administrative tasks and towards stewarding their ancestral lands. Tribes could expand their fire practitioner workforce, treat larger areas of land, and better conserve important natural and cultural resources.

Recommendations

We recommend that Congress:

- Commission a study conducted collaboratively with Tribal nations and organizations to explore financial mechanisms to deliver consistent, direct funding to Tribal Nations and organizations for Cultural Fire purposes. Potential mechanisms could include a federal endowment or a dedicated tax.

- Direct the study to ensure that proposed funding mechanisms would be easily accessible for CFPs to obtain funding.

- Once the appropriate financial mechanism is identified, employ regional Tribal liaisons to direct the funding to Tribes and to receive input from local communities and CFPs. The liaisons would help to create two-way communication channels that empower local voices in a funding process that has been historically top-down.

By drawing upon the expertise of communities and Cultural Fire Practitioners, the Tribal liaisons would be able to target funds to groups and landscapes that have the greatest need, ensuring that federal resources are utilized in an effective manner each year.

It is time for the federal government to recognize the deep expertise of Tribes in fire management. By giving Tribes greater influence in determining the use of funds for preventative and mitigative activities, Congress would bring funding structures in line with the rightful sovereignty of Tribes, and it would protect communities and natural resources across the country by clearing the path for more beneficial fire.

Create a categorical exclusion in the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for Cultural Burning

Nina Fontana, PhD, University of California, Davis; Chris Adlam, PhD, Oregon State University

One of the original stated purposes of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 is “to promote efforts which will prevent or eliminate damage to the environment and biosphere and stimulate the health and welfare of man.” Cultural and prescribed burning directly contribute to this goal. Unfortunately, current interpretations of NEPA require Cultural Fire Practitioners (CFPs) to undertake onerous Environmental Impact Statements before burns on federal or Tribal trust lands, which often prevent Tribes from even attempting to burn in these locations. Because Tribal lands are held in trust by the federal government, CFPs must also comply with NEPA regulations that were designed to govern federal actions. This arrangement limits Tribal sovereignty and imposes an undue burden.

To bring the implementation of NEPA in line with its purpose, NEPA should recognize cultural burning as part of the background condition of our natural environment here in the United States. Tribes have utilized these cultural burning practices for centuries, even millenia, to manage the fire-prone landscapes within the United States, including taking measures to protect ancient wildland urban interfaces in the Southwest. Through this long history, cultural burning has fundamentally influenced what we consider to be our human environment today. For that reason, cultural burning should be classified as a categorical exclusion.

Current guidelines on implementing NEPA include a categorical exclusion for “Prescribed burning to reduce natural fuel build-up and improve plant vigor,” as long as the project does not require the use of herbicides or over 1 mile of low standard road construction (DOE NEPA Guidelines). Additionally, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act categorically excluded “establishing and maintaining linear fuel breaks” for the purpose of wildfire risk mitigation under specific circumstances.

The following recommendations represent several pathways for Congress to encourage cultural burning. By implementing one or all of these measures, Congress would begin the process of recognizing burning as a sovereign right for Tribes (similar to hunting and plant gathering) and therefore exempt from permitting.

Recommendations

To these ends, Congress should consider:

- Acting to statutorily exclude cultural burns from a detailed environmental analysis, recognizing cultural burning as part of a landscape’s natural baseline condition.

- Alternatively, direct federal agencies to consider creating categorical exclusions for cultural burns.

- Delegating to Tribal governments and organizations the authority to craft permitting processes and to issue permits on Tribal trust lands.

- Utilizing federal definitions of “Cultural Fire Practitioner” and “Cultural Fire” to help provide guidelines for which activities are to be considered a cultural burn. Alternatively, region-specific guidelines can be developed by working groups composed of representatives from Tribal Nations and organizations.

- Creating a dedicated and specially trained team of NEPA practitioners to handle surge capacity for permitting for cultural burning and to provide Tribes with guidance on how to navigate NEPA requirements for land stewardship activities.

By carrying out these recommendations, Congress would bring the implementation of the National Environmental Policy Act in line with its original purpose and create positive impacts on the ground for communities across the nation.

Legally define “Cultural Fire Practitioner” and “Cultural Fire” to encourage Cultural Burning

Raymond Gutteriez, Member of Wuksachi Band of Mono Indians

Cultural Fire Practitioners (CFP) have the knowledge, experience, and willingness to help lead the restoration of more sustainable fire regimes to their ancestral homelands. However, they are currently dissuaded from carrying out cultural burns for a variety of reasons including fear of liability, burdensome regulations, burn bans, and resource constraints. In addition, Cultural Fire Practitioners receive limited support from the federal government for their important work.

As an important first step in encouraging cultural fire, Congress should direct the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the US Department of the Interior (DOI) to develop regionally-specific definitions of ‘cultural fire’ and ‘Cultural Fire Practitioner’ through a process led by Tribal governments.

Currently, the federal government does not adequately recognize cultural fire, despite its deep-rooted traditional significance for Tribal Nations and its potential benefits for forest and wildfire management across the country. Because of this lack of recognition and other barriers, many CFPs have not been able to carry out their cultural fire traditions. Those that have continued to implement cultural fire have had to operate with minimal federal support and with higher personal risk. In addition, they have been forced to significantly alter their traditions and practices to fit existing legal processes and definitions that were designed for prescribed burns. These factors have combined to make cultural burning prohibitively difficult to implement on federal, tribal, and state lands.

Recommendations

In order to provide the proper legal framework needed to enable and support cultural burning, Congress should:

- Direct USDA and DOI to participate in a process led by Tribal governments and Tribally-led organizations to develop regionally-appropriate definitions of ‘cultural fire’ and ‘cultural fire practitioner’. These definitions would differentiate cultural fire from the separate risk reduction strategy that is prescribed burning. Cultural burning includes diverse purposes that are not captured under current definitions of prescribed burning, including preservation and stewardship of culturally relevant plants and animals.

- Ensure that definitions include all Tribal entities, not just federally recognized Tribes.

- Direct agencies to consider how these definitions can be used to address barriers for cultural burning.

- Explore opportunities to use this definition to support cultural burning.

These definitions will create a legal foundation that can be used to expand the role of cultural burners and ease restrictions, in a manner similar to that of California’s own legislation defining cultural burning (CA SB 332; CA SB 926; CA AB 642). In tandem with adopting a formal definition, California implemented a gross negligence standard that limited the financial liability of CFP who take appropriate precautions before a fire.

Federal agencies can explore opportunities to use the definitions to support cultural burning. For example, federally recognized CFPs could be provided with exemptions from having to obtain formal National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) qualifications and/or from the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) environmental assessment process. The federal government could also support creation of an easily accessible federal indemnity fund that provides support to cultural burners.

By codifying these definitions, the federal government would take a key step in elevating the visibility and status of Cultural Fire Practitioners as key partners in land stewardship and wildfire risk reduction and management.

Expand the scope and funding of the Tribal Forest Protection Act of 2004

Raymond Gutteriez, Member of Wuksachi Band of Mono Indians

Under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 and the Tribal Forest Protection Act (TFPA) of 2004, Tribes are able to propose and execute projects (called 638 projects) on USFS-managed and BIA-managed land which (i) borders or is adjacent to Indian trust land, and (ii) poses a fire, disease, or other threat to Tribal forest or rangeland or that otherwise requires land restoration activities. Unfortunately, 638 projects are rarely proposed or implemented due in large part to lack of funding and its limited scope of only including tribes that possess land adjacent to federally managed lands.

Congress should appropriate dedicated funding for ‘638’ projects and expand the range of the TFPA to include the ancestral homelands of Tribal Nations.

The aforementioned 638 law was enacted to promote “maximum Indian participation in the Government,” but it fails at this goal in its current form. The initiative has been hampered by the fact that “no specific funding was appropriated or authorized for 638” projects (USFS). Instead, funding is expected to be obtained from other sources of funds for activities on federal lands, which often require prohibitive amounts of administrative burdens for Tribes to compete for and obtain. Additionally, many Tribes are ineligible to participate in 638 projects because they do not possess lands that are adjacent to national forests, even though those national forest lands are part of their ancestral homelands.

Recommendations

We recommend that Congress consider:

- Appropriating dedicated funding for 638 projects. By creating a dedicated source of funding for this class of project, Congress would help to protect national forestlands by encouraging risk reduction and restoration activities on federal lands.

- Expanding the range of eligibility for 638 projects to include the ancestral homelands of Tribal Nations and Tribal organizations.

In addition, these changes can be paired with other efforts to expand Tribal authority and ability to plan, implement, and review prescribed and cultural burns on federal lands.

Reduce federal subsidies for development that might exacerbate fire risk

Max Moritz, Adjunct Professor, UC Santa Barbara

Federal spending on wildfire suppression has ballooned in the past four decades. Despite these efforts, property damage due to wildfire continues to escalate, devastating communities and robbing tens of thousands of people of treasured homes, businesses, and gathering places.

This is in part because more and more Americans are living and working adjacent to wildlands, where they are more vulnerable to wildfire impacts. In 2020, 4.5 million homes were located in areas of “high or extreme wildfire risk.” To make matters worse, fires on state, local, and private land have doubled in size (on average) since 1991. While decisions about land use and urban planning are made locally, there are important opportunities for crucial guidance at the federal level to help mitigate harm to communities.

Congress should direct agencies to determine to what extent and through what mechanisms federal dollars are subsidizing development in a manner that perpetuates fire risk.

Where and how we build our communities can influence fire probabilities in the broader region surrounding a particular development, crossing administrative boundaries and even state lines.

Money from federal agencies supports development of homes and related infrastructure. Failing to identify and address when and how federal funds may be subsidizing development in wildfire hazard risk areas will continue to exacerbate social and economic losses.

The federal government should investigate to what extent and through which programs it is subsidizing development in a manner that exacerbates fire risk. Using this information, Congress and agencies can take action through existing mechanisms to support local and regional planning that is both fire-resilient and equitable.

Recommendations

Congress should:

- Create an interagency working group to identify all federal planning, housing, infrastructure and mitigation/recovery budgets, policies, and authorities that impact built environments in wildfire hazard areas and deliver this information to Congress.

Using this information, Congress can consider whether it would be appropriate to take one or more of the following actions:

- Develop specific guidance on constructing and adopting fire hazard and land use planning maps that consider wildfire risk, mitigation, and management, in addition to resiliency goals at the state and local levels. This could include creating centralized fire hazard maps, as well as parcel-level maps of vulnerabilities (e.g., socio-economic factors, evacuation constraints) and available mitigation options.

- Informed by guidance on fire hazard maps, set voluntary standards for resilient siting and construction to make new development safer and more survivable. This could include developing and recommending new building codes that exceed current fire standards in medium- or high hazard areas, in addition to landscape-specific mitigation strategies, and community evacuation preparedness strategies.

- Require that recipients of federal funds for infrastructure projects meet a set of fire-resilient development standards for building codes and community siting criteria.

- Communities possess varying capacities for implementing federal standards. The federal government should prioritize funding and technical assistance for vulnerable communities looking to meet federal standards for new fire-resilient development and should take into consideration a variety of mitigation options, from citing development in safer locations to resilient building approaches.

Should the federal government choose to take action on any of the recommendations above, there are important considerations Congress and agencies must keep in mind.

- Housing demand and equity. In actions on this topic, the federal government must take care not to penalize rural development or development in low-income communities. Housing supply and infrastructure needs must be balanced with fire resilience.

- Existing legislation and precedent. There are legislative precedents for how new federal guidance could be implemented. California legislation provides a precedent for 1) using fire hazard maps to guide building codes and 2) methods for citing new development to avoid the most hazardous locations, as long as housing needs overall can be met.

- Challenges with hazard mapping. A core challenge for these approaches is identifying what portions of landscapes are “hazardous” in the context of fire and mapping this in a scientifically consistent way. There is also federal legislation supporting fire risk mapping related to allocation of FEMA relocation assistance after wildfire disasters, which may augment existing federal fire hazard mapping efforts.

Public Health and Infrastructure

Make smoke management a core goal of wildland fire management

Alistair Hayden, Assistant Professor of Practice, Department of Public & Ecosystem Health, Cornell University

Toxic smoke from wildland fire spreads far beyond fire-prone areas, killing many times more people than the flames themselves and disrupting the lives of tens of millions of people. Despite this, wildfire smoke is often reported and managed separately from other wildfire impacts.

Congress should establish smoke management as a core goal of wildland fire management and create institutional capacity to achieve that goal.

The 2014 National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy describes a vision for the century: “To safely and effectively extinguish fire, when needed; use fire where allowable; manage our natural resources; and as a Nation, live with wildland fire.” Significant research conducted since the publication of the Strategy indicates that wildfire smoke impacts people across the United States, causing 10,000 deaths and billions of dollars of economic losses annually. Smoke impacts exceed their corresponding flame impacts; yet, wildfire strategy and funding largely focus on flames and their impacts.

In order to ensure that all impacts of wildland fire, including smoke, are addressed efficiently and comprehensively, Congress should take actions that establish wildfire smoke management as a core goal of wildfire management.

To ensure that wildland fire smoke is considered as a core wildland fire hazard, Congress should consider amending relevant legislation to specifically account for smoke.

For example, Congress could:

- Amend the Stafford Act Sec. 102 to list smoke as a Major Disaster.

- Pass the Wildfire Smoke Emergency Declaration Act of 2021.

- Amend the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, And Recreation Act of 2019 Section 1114 to promote technology to track smoke emissions and impacts, and to extend smoke forecasts to future emissions based on land-management strategies.

- Amend the Federal Land Assistance, Management, and Enhancement Act of 2009 (FLAME Act) Sec. 3 to require that smoke be considered in the National Cohesive Strategy.

Current interagency wildfire leadership groups occasionally consider smoke in the context of wildland fire impacts and management. To ensure wildfire strategy discussions always include modern smoke-management considerations, these groups should include agencies with expertise on smoke data and impacts (e.g., Environmental Protection Agency, Center for Disease Control, National Aeronautics and Space Administration).

Congress should therefore:

- Amend the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Sec. 70203(b) and the FLAME Act Sec. 3 to include smoke-expert agencies in development of the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy.

- Pass new policy adding smoke-expert agencies to wildfire-policy collaborations, including the National Interagency Fire Center, National Wildfire Coordinating Group, and the Wildland Fire Leadership Council.

To succeed, Congress should also allocate funding for smoke management programs described in companion suggestions (here and here).

Foster smoke-ready communities to save lives and money

Alistair Hayden, Assistant Professor of Practice, Department of Public & Ecosystem Health, Cornell University

In the US, more and more people are being exposed to wildfire smoke—27 times more people experienced extreme smoke days than a decade ago. Wildfire smoke poses higher risks to outdoor workers, unhoused individuals, children, older adults, and people with diabetes or heart disease.

The federal government can equitably save lives and money by helping communities prepare for, identify, and respond to smoke events.

Recommendations

Congress should designate some of the annual $6+ billion in wildfire management to create funding for households and public spaces to improve indoor air-quality during heavy smoke.

To help communities prepare for smoke events:

- The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) should designate air filtration and weatherization as eligible for Hazard Mitigation Assistance grants.

- FEMA’s Benefit-Cost Analysis, which determines grant funding eligibility, should consider the health benefits of reducing smoke exposure.

- FEMA should incentivize building community-appropriate, smoke-resistant, multi hazard resilience hubs.

To ensure communities are able to identify potentially deadly smoke events, Congress should:

- Direct the Environmental Protection Agency and Occupational Safety and Health Administration to define harmful air due to wildfire smoke. Both have definitions of harmful air quality based on constituent particles, but wildfire smoke is more toxic than particles from other sources (for an example law, see California Code of Regulations, Title 8, Section 5141.1).

To provide communities with support needed to act during smoke events, Congress should:

- Pass the Wildfire Smoke Emergency Declaration Act of 2021 to enable FEMA to provide emergency assistance to smoke-impacted communities (including grants, equipment, supplies, and personnel and resources for establishing smoke shelters and air-quality monitors) and the Small Business Administration to provide grants to small businesses that lose revenue due to smoke. These actions should be taken in concert with efforts to support long-term resilience and, where possible, should provide support that can be applied in recurring smoke emergencies.

- Amend the Stafford Act Sec 420 to automatically provide smoke mitigation support as part of the commonly used Fire Management Assistance grant program.

Build data infrastructure to support decision making based on smoke hazards

Alistair Hayden, Assistant Professor of Practice, Cornell University; Teresa Feo, Senior Science Officer, California Council on Science and Technology

National spending on fire suppression exceeds $4 billion in the fiscal year 2023 funding bill, while less than $10 million is allocated for smoke management. This 600:1 funding ratio for fire compared to smoke is misaligned to the 1:1 ratio of economic impacts and 1:100 ratio of fire to smoke deaths.

Data infrastructure critical for minimizing these smoke-related hazards is largely absent from our firefighting arsenal.

Congress should take action to better leverage existing smoke data in the context of wildland fire management and fill crucial data infrastructure gaps to enable smoke management as a core part of wildland fire management.

Some smoke data is already collected, including smoke forecasts for active fires from the Interagency Wildland Fire Air Quality Response Program and retrospective smoke emissions totals from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the National Emissions Inventory (NEI). However, these smoke impacts are considered separately from flame impacts (e.g., structures burned), and are left out of broader wildfire strategy. New authoritative realtime smoke-data tools need to be created and integrated into wildfire management strategy.

Recommendations

To better track health impacts of wildfire smoke, Congress should:

- Direct the CDC to create a retrospective data inventory estimating morbidity and mortality due to smoke for individual wildland fires and publish their findings in National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) wildfire impact summaries.

- Direct the CDC to increase epidemiologist access to the National Vital Statistics System, to enhance the scientific community’s ability to study possible linkages between smoke and health impacts.

To better integrate smoke data with other fire data, Congress should:

- Expand the NIFC to include smoke in its mission, and rename it as the National Interagency Fire and Smoke Center.

- Direct EPA and CDC to join the NIFC collaboration and place staff at NIFC headquarters.

- Require the expanded NIFC to develop smoke-impact data products, including smoke deaths and smoke-plume footprints, for each fire and publish them alongside common fire data products like structures and area burned.

- Direct NOAA or EPA to create high-resolution daily datasets of wildfire-attributable air pollutants nationwide, make these data available in real-time, and integrate them with the NEI.

To enable the consideration of smoke-related health impacts in wildland fire management, Congress should:

- Direct EPA to define wildfire-specific concentration-response functions for use in estimating health impacts in the BenMAP-CE tool.

- Direct NIH to create Research-Center-scale grants to study health impacts of wildfire smoke. Direct NIH to hire new staff to translate the findings for wildfire management strategists.

- Direct the USFS, CDC, and EPA to continue researching the health impacts of smoke from different types of wildland fire (e.g., prescribed burns compared to unplanned wildfires), hiring new staff as appropriate. A more detailed understanding is critical to optimizing prescribed-burn strategy.

- Direct the NIFC, USFS, EPA, and CDC to create models linking parcel-specific landscape management to long-term smoke emissions and resulting health impacts (and hire new staff as appropriate). These models are critical to optimizing location-specific prescribed burn strategies and to evaluating the smoke-related public health tradeoffs of alternative management strategies (e.g., prescribed burn strategies compared to suppression-focused strategies of the past).

The suggested additions would improve national technical ability to increase smoke-related safety, thereby saving lives and reducing smoke-related public health costs.

Support strategic deployment of community resilience hubs to mitigate smoke impacts and other hazards

Lee Ann Hill, Director of Energy and Health, PSE Healthy Energy

Exposure to wildfire smoke can have severe impacts on human health, including higher risk of respiratory problems, heart attack, stroke, and premature death. One tool communities can use to build resilience to smoke and other hazards that threaten human health are resilience hubs. Resilience hubs are indoor community spaces designed to address overall community vulnerability and to foster public safety, security, and wellbeing. Resilience hubs can also support communities amid emergencies, including smoke emergencies, by providing access to clean indoor air.

The federal government can foster holistic community resilience to wildfire smoke impacts and other hazards by supporting the development of community resilience hubs.

Public health guidance and climate adaptation policies should account for the reality that many communities will be exposed to multiple hazards, sometimes concurrently. Rather than address specific exposures (e.g., wildfire smoke or extreme heat) in isolation, policymakers should consider mitigation approaches that will build capacity to prepare for and withstand multiple hazards, including those associated with 1) mitigation strategies (e.g., prescribed fire smoke), 2) extreme weather events (e.g., smoke, extreme heat) and natural disasters, and 3) power outages. Policymakers can prioritize policy interventions that reduce harmful smoke exposures while also expanding broader community resilience to maximize the human health benefit of every dollar spent.

Community resilience hubs equipped with heating, ventilation, and air conditioning and powered by distributed clean energy resources can reduce harmful smoke exposures while expanding broader community resilience amid extreme weather events, natural disasters, and grid outages. Local governments across the United States and Canada have established resilience hubs focused on disaster and emergency response; pilot efforts to build resilience more holistically are underway in Baltimore, Maryland and Northern California.