Countering China’s Monopolization of African Nations’ Digital Broadcasting Infrastructure

Summary

The majority of people living in the African continent access their news and information from broadcasted television and radio. As African countries follow the directive from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to migrate from analog to digital broadcasting, there is an urgent need to sequester the continent’s broadcast signal distributors (BSDs).1 BSDs provide the necessary architecture for moving broadcasted content (e.g., television and radio) into the digital sphere.

Most BSDs in Africa are owned and operated by Chinese companies. Of 23 digitally migrated countries, only four BSDs (Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, and Zimbabwe) are officially known to be outside the influence of China-based companies. The implicit capture of the BSD marketplace by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) threatens African democracies and could undermine international partnerships among African nations and with the United States. Excessive Chinese control over African BSDs also raises security concerns and impedes establishment of a robust, competitive, and rules-based global market in communications infrastructure.

The United States should therefore consider the following actions to support African civil society, media regulators, and legislators in securing an information ecosystem that advances democratic values:

- Creating a Program on Traditional and Digital Media Literacy within the Department of State’s Bureau of African Affairs 2021 Africa Regional Democracy Fund.

- Supporting a Regional Digital Broadcasting Coordinator for each of the five African sub-regional groups, via the Digital Ecosystem Fund and the Digital Connectivity and Cybersecurity Partnership.

- Enhancing U.S.-based competitiveness by expanding the Digital Attaché Program to promote alternative BSDs in Africa.

- Leveraging the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit proposed in the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act to advance a regulatory and liability framework governing the relationships among BSDs, content producers, and constitutional protections.

Ensuring Manufacturing USA Reaches Its Potential

Summary

President Biden made advanced manufacturing a major policy priority during his campaign, including calling for a significant expansion of manufacturing programs to reach 50 communities through new manufacturing-technology hubs. Expanded manufacturing programs will invest in our nation’s long-term competitive innovation capacity. However, building these programs successfully requires a thoughtful and practical implementation plan. This memo presents two categories of recommendations to improve the U.S. advanced-manufacturing ecosystem:

1. Improve the existing Manufacturing USA institutes. Some new institutes are needed, but the Administration should concentrate first on strengthening support for the 16 existing Manufacturing USA Institutes, renewing the terms of institutes that are performing well, and expanding the reach of those institutes by launching more workforce-development programs, regional technology demonstration centers, initiatives to engage small- and mid-sized manufacturers and build regional manufacturing ecosystems.

2. Implement a multi-part strategy for collaboration among the Institutes: First, the Administration should create a “network function” across the Manufacturing USA Institutes because firms will need to adopt packages of manufacturing technologies not just one at a time. This could be supported by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and would combine the advances of different Institutes and package them to be integrated and interoperable for easy adoption by firms. Second, a NIST-led traded-sector-analysis unit should be created to evaluate the manufacturing progress of other nations and inform Institute priorities. Third, the Administration should provide research and development (R&D) agencies with resources to build manufacturing-related R&D feeder systems (e.g., an expanded pipeline of manufacturing technologies) that aligns with Institute needs. Fourth, the administration should establish an Advanced Manufacturing Office within the White House National Economic Council to coordinate and champion all of the above, as well as numerous other manufacturing programs.

Making the Trade Adjustment Assistance Program Work for the New Economy

Summary

Existing technology could automate nearly half of all work activities today. As society continues to embrace artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and automation, companies will need fewer workers or workers with new skills, leading to displacement. The government must assist the American workforce with acquiring skills demanded by the modern workplace and support workers in transitioning to the new economy. To do so, the Biden-Harris administration should push Congress to evolve the Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program into the Trade and Technology Adjustment Assistance program (TTAA) to help workers displaced not just by trade but also by advancements in emerging technologies, such as AI and robotics.

The expanded TAA program should include (1) a centralized administrative infrastructure, (2) a cutting-edge and comprehensive upskilling platform, and (3) “rainy day” funds for temporary worker assistance. The comprehensive upskilling platform, in particular, sets the proposal outlined in this memo apart from other proposals to update TAA, such as the TAA for Automation Act of 2019. The TAA for Automation Act aims to include workers displaced by automation as a group eligible for TAA services. TTAA proposed herein goes further, seeking to rethink TAA’s upskilling and training component from the ground up.

American Rescue Plan Funding: A Playbook for Efficiently Getting the Lead Out

Summary

Lead is a neurotoxin that continues to harm communities across the country. Though new uses of lead in paint, gasoline, and pipes have been banned for several decades, lead in legacy products and materials remains in communities, posing an ongoing threat to human and economic development. Anywhere from 6 to 10 million residential lead service lines (LSLs), for instance, are still in use nationwide.

Funding included in American Rescue Plan (ARP) grant programs gives cities and states the opportunity to finally eradicate lead contamination in water lines. These steps outlined in this memo (and summarized in the figure below) represent a data- driven approach to rid American communities of the pernicious effects of lead contamination in water systems. This approach builds on research from the University of Michigan and subsequent implementation by BlueConduit in more than 50 cities in the United States and Canada.

Incorporating Health and Safety Data in CareerOneStop Websites to Optimize Career-change Guidance

Summary

The Department of Labor (DOL) should update CareerOneStop’s “mySkills myFuture” website and other web properties to provide prospective career changers with comparative information on job-related pollution and safety metrics.

As the United States transitions towards a clean energy economy, a majority of workers in traditional fossil fuel industries will need to find new employment. In its January 27, 2021 Executive Order “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad”, the Biden-Harris Administration called for revitalizing “energy communities” — that is, communities whose economies have traditionally been based on the energy industry. Revitalization includes creating good and sustainable opportunities for labor. DOL is a member of the Interagency Working Group on Coal and Power Plant Communities and Economic Revitalization authorized by the January 27th Executive Order, which has been tasked with providing federal leadership to support coal, oil and gas communities during the energy transition. DOL’s “mySkills myFuture” interactive web portal guides experienced job seekers to discover new careers that match their existing skill sets. However, information presented on the portal lacks key quantitative factors that support worker well-being. To enable transitioning workers in declining fields to make more informed choices about future jobs, the DOL should update its career guidance tools to include data on health and safety risks associated with different job options.

Reevaluating U.S. Military Use of Drone Technology

In the 21st century, drone technology has become commonplace in warfare. In fact, drones are increasingly preferred by both state and non-state actors over other modes of warfare. But widespread use of drones in war engenders considerable controversy. Civilian casualties and collateral damage have grown alongside drone deployment with little accountability or transparency. As the Biden-Harris Administration works to rebuild America’s place on the world stage and as a member of the global community, the Administration should boost accountability for civilian deaths by rethinking when and how drones are used. Specifically, the Administration should (1) sign an executive order to boost transparency and oversight of drone technology used by the military, (2) work with Congress to review use of drones in U.S. military operations, and (3) lead efforts to launch an international drone accountability regime.

Challenge and Opportunity

In the last two decades, the use of drone strikes by the U.S. military against terrorist and militant organizations has expanded. Drones have been utilized so frequently by the U.S. government because they offer numerous advantages over manned aircraft. Drones are a cost-effective way to keep American boots off the ground and safe from danger. The fact that drones lack a human pilot means that fatigue is also lessened in military operations. Drone operators can hand off controls without any downtime, and drones can offer the same accuracy and lethality as manned aircraft. Drones can also serve as a valuable tool in surveillance operations.

But there is also a downside to this technology that makes warfare easy. Commanders are more likely to greenlight attacks when those attacks pose less of a direct risk to American military personnel. As the use of drones has proliferated, so too have the number of drone strikes ordered by the U.S. military — and the accompanying losses of civilian life.

Beginning in the early 2000s and into President Obama’s Administration, the use of drone technology increased. A 2005-2030 roadmap published by the Department of Defense noted that twenty types of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) were flown for 100,000 hours in conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Under President Obama, an estimated 3,797 people, including 324 civilians, were killed in the 542 strikes carried out during the eight years of his Administration. This was the result of a dramatic increase in drone warfare. In his second term, President Obama took steps to reign in the use of drone warfare but beginning in 2017, President Trump’s Administration took it to new heights. In his first two years in office, President Trump launched more drone strikes that President Obama did in eight years. Reporting suggests that with the use of drones, President Trump launched more attacks in Yemen than all previous U.S. presidents combined. These drone strikes together killed between 86 and 154 civilians.

President Obama signed Executive Order 13732 in 2016, which required the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to review and investigate drone strikes involving civilian casualties and offer payment to families of those killed. The executive order also required the Director of National Intelligence to release annual summaries of all U.S. drone strikes conducted, accompanied by assessments of how many civilians died as a result of those strikes. But President Trump revoked this policy in 2019, arguing that the provisions were superfluous and distracting. As the use of drones increased dramatically in the first year of President Trump’s Administration, the United States also disclosed fewer details about the frequencies and fatalities of these strikes.

The time is ripe for the Biden-Harris Administration to reevaluate and rein in the use of drone warfare to both boost U.S. accountability for civilian deaths and restore America’s leadership on the world stage.

Plan of Action

The Biden-Harris Administration should take three essential actions to improve transparency and oversight of U.S. drone operations. These actions are crucial to restoring America’s place and reputation in the international community.

First, President Biden should sign an executive order committing to boost transparency and oversight of drone technology used by the U.S. government. On the first day of his Administration, President Biden imposed temporary limits on drone strikes outside of battlefields in Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq and ordered a review of U.S. drone policy with respect to counterterrorism operations. This was a welcome step, and the Administration can build on it to promote greater transparency without compromising U.S. national security. An Executive Order to Reevaluate U.S. Military Use of Drone Technology to Boost Accountability for Civilian Deaths can and should reinstate much of Executive Order 13732, but also go further. Specifically, the executive order should:

- Commit to reduce the use of drone strikes overall.

- Commit to limit collateral damage when drone technology is used.

- Require the CIA to release biannual summaries of U.S. drone strikes, accompanied by assessments of civilian casualties.

- Offer payment to the families of civilians killed as a result of a U.S. drone strikes.

- Require the CIA, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Defense to conduct a thorough joint investigation of all drone use resulting in civilian deaths.

- Provide quarterly briefings to Congress on the use of drone technology and provide reports to relevant Congressional committees on investigations into drone strikes that result in civilian casualties.

To complement this executive order, the Biden-Harris Administration’s review of U.S. drone policy should include an interagency process involving the CIA, the National Security Council (NSC), and the Departments of Defense, State, and Justice to evaluate the increased use of drones over the past decade, analyze trends in technology shaping the future use of drones, and devise a coordinated path forward to (1) increase accountability for use of drone warfare, and (2) boost American national security through a strategic counterterrorism strategy that minimizes the extraneous use of drones.

Second, President Biden should work with Congress to review the use of drones in U.S. military operations, including use of drones both within and beyond active military conflict. The Administration should provide members of key Congressional committees (e.g., the Senate Foreign Relations, Armed Services, and Intelligence Committees as well as the House Foreign Affairs, Armed Services, and Intelligence Committees) with both classified and public briefings on the Administration’s counterterrorism strategy and the role of drone technology in advancing military operations. Congress, in turn, should conduct public hearings on these topics and should ultimately act to repeal and replace the outdated 2001 and 2002 Authorizations for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) which have been used by multiple presidents to justify continued military action across the globe, including drone strikes.

In fact, the Biden-Harris Administration has pushed for these AUMFs to be replaced with a “narrow and specific framework that will ensure we can protect Americans from terrorist threats while ending forever wars,” according to a statement by Press Secretary Jen Psaki in March 2021. The 2001 AUMF was passed after the Sept 11. Terrorist attacks and the 2002 AUMF was passed in the fall of 2002 ahead of the U.S.- led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Third, as one of the largest producers and sellers of drone technology worldwide, the United States should lead efforts to launch an international drone accountability regime. This effort, which could be launched through an existing international organization like the United Nations, would bring together states to:

- Sign a treaty that creates a commitment to abide by a set of international standards on the use of drone warfare, including a commitment to reduce collateral damage and loss of civilian life.

- Review and evaluate use of drone technology by nation, especially by global military leaders.

- Investigate and make public instances of drone-technology abuse.

The global accountability effort will require development of a strong set of international standards that regulate the use of drone technology — standards that will make the United States and the world safer. These international standards should include commitments by abiding states and non-state actors to: (1) commit to reducing the use of drone strikes and limiting collateral damage; (2) issue a public statement following drone strikes resulting in civilian casualties explaining the reason for the strike and relevant surrounding circumstances; and (3) publish summaries of all casualties and damage resulting from drone strikes. (4) Additionally, abiding parties that sell or purchase drone technology should commit to only sell or purchase drone technology from other abiding parties.

Conclusion

The growing ubiquity of drone strikes within U.S. military operations demands action to increase transparency and accountability. When drone strikes are used too freely, unnecessary civilian casualties can result — as recent history has already demonstrated. By strategically rethinking how the United States uses drones for warfare, the Biden-Harris Administration can rebuild accountability for civilian deaths, restore transparency to our nation’s use of drone technology, and repair our nation’s reputation on the world stage, all without compromising military operations or national security.

President Biden can take immediate action by issuing an executive order that builds on the drone-accountability policies put in place during the late Obama era while setting a new standard for the international community, as well as by ordering an interagency review of the role that drones play in U.S. operations. Further, President Biden should work with Congress to repeal and replace the outdated 2001 and 2002 AUMFs and to consider how drones can and should be used responsibly in warfare. These steps will be essential to restoring confidence in U.S. military operations both at home and abroad. Finally, as the U.S. seeks to rebuild its position in the global community, efforts led by the Biden-Harris Administration to establish an international drone-accountability regime can help check the growing use of drones in warfare globally: a result that will strengthen the security of the United States and the world.

The unmanned nature of drone warfare does indeed limit U.S. military casualties. But the widened use of drone warfare by the American military and resulting casualties poses risks to Americans. Civilian casualties and collateral damage that result from reckless drone strikes in many instances have provoked the targets of those strikes to retaliate against American troops.

Using AI and Virtual Reality/Augmented Reality to Deliver Tailored and Effective Jobs Training

Summary

To address the critical challenges of lifelong learning, evolving skills gaps, and continuous labor market transformation and automation, all Americans need to have access to agile and effective jobs training. Artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality/augmented reality (VR/AR) capabilities can deliver training tailored to the unique backgrounds, preferences, and needs of every individual. In this memo, we propose a two-stage approach that the Biden-Harris administration can adopt to help prepare Americans for the jobs of the future through responsible use of AI and VR/AR.

Stage 1 would launch a one to three pilot programs that leverage AI and VR/AR technologies to provide targeted training to specific communities.

Stage 2 would establish a national prize competition soliciting proposals to build and deliver a federal lifelong learning platform for the nation.

Improving Data Infrastructure to Meet Student and Learner Information Needs

Summary

The Congress should dedicate $1 billion, 1 percent of the proposed workforce funding under the American Jobs Plan, for needed upgrades to Statewide Longitudinal Data Systems (SLDS). Major upgrades are needed to Statewide Longitudinal Data Systems to enable states to effectively monitor and address long-term pandemic learning loss, while ensuring this generation of students stays on track for college and career in the aftermath of the pandemic. With the major influx of planned resources into K12 and postsecondary education from the recent and upcoming relief bills, there is also a critical need to ensure those funds are targeted toward students and workers who are most in need and to measure the impact of those funds on pandemic recovery. Some states, such as Texas and Rhode Island, are already leveraging funds from previous relief bills (e.g., Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES Act), to modernize their data systems, offering a model for other states to connect education, workforce, and social services information. This demonstrates an interest and need among states for SLDS upgrades, though additional investment is necessary to address historically underfunded data infrastructure.

An Institute for Scalable Heterogeneous Computing

Summary

The future of computing innovation is becoming more uncertain as the 2020s have brought about a pivot point in the global semiconductor industry. We owe this uncertainty to several factors, including the looming end of Moore’s Law, disruptions in semiconductor supply chains, international competition in innovation investment, a growing demand for more specialized computer chips, and the continued development of alternate computing paradigms, such as quantum computing.

In order to address the next generation of computing needs, architectures are beginning to emphasize the integration of multiple, specialized computing components. Within this framework, the U.S. is well poised to emerge as a leader in the future of next-generation computing, and more broadly advanced semiconductor manufacturing. However, there remains a missing link in the United States’ computing innovation strategy: a coordinating organization which will down-select and integrate the wide variety of promising, next-generation computing materials, architectures, and approaches so that they can form the building blocks of advanced, high-performance, heterogeneous systems.

Armed with these facts, and using the existing authorization language in the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), the Biden Administration and Congress have a unique opportunity to establish a Manufacturing USA Institute under the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) with the goal of pursuing advanced packaging for scalable heterogeneous computing. This Institute will leverage the enormous body of previous work in post-Moore computing funded by the federal government (Semiconductor Technology Advanced Research Network (STARnet), Nanoelectronics Computing Research (nCORE), Joint University Microelectronics Program (JUMP), Energy-Efficient Computing: From Devices to Architectures (E2CDA), Electronics Resurgence Initiative (ERI)) and will bridge a key gap in bringing these R&D efforts from the laboratory to real world applications. By doing this, the U.S. will be well positioned to continue its dominance in semiconductor design and potentially regain advanced semiconductor manufacturing activity over the coming decades.

Ensuring Good Governance of Carbon Dioxide Removal

Climate change is an enormous environmental, social, and economic threat to the United States. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from burning fossil fuels and other industrial processes are a major driver of this threat. Even if the world stopped emitting CO2 today, the huge quantities of CO2 generated by human activity to date would continue to sit in the atmosphere and cause dangerous climate effects for at least another 1,000 years. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has reported that keeping average global warming below 1.5°C is not possible without the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR).2 While funding and legislative support for CDR has greatly increased in recent years, the United States does not yet have a coordinated plan for implementing CDR technologies. The Department of Energy’s CDR task force should recommend a governance strategy for CDR implementation to responsibly, equitably, and effectively combat climate change by achieving net-negative CO2 emissions.

Challenge and Opportunity

There is overwhelming scientific consensus that climate change is a dangerous global threat. Climate change, driven in large part by human-generated CO2 emissions, is already causing severe flooding, drought, melting ice sheets, and extreme heat. These phenomena are in turn compromising human health, food and water security, and economic growth.

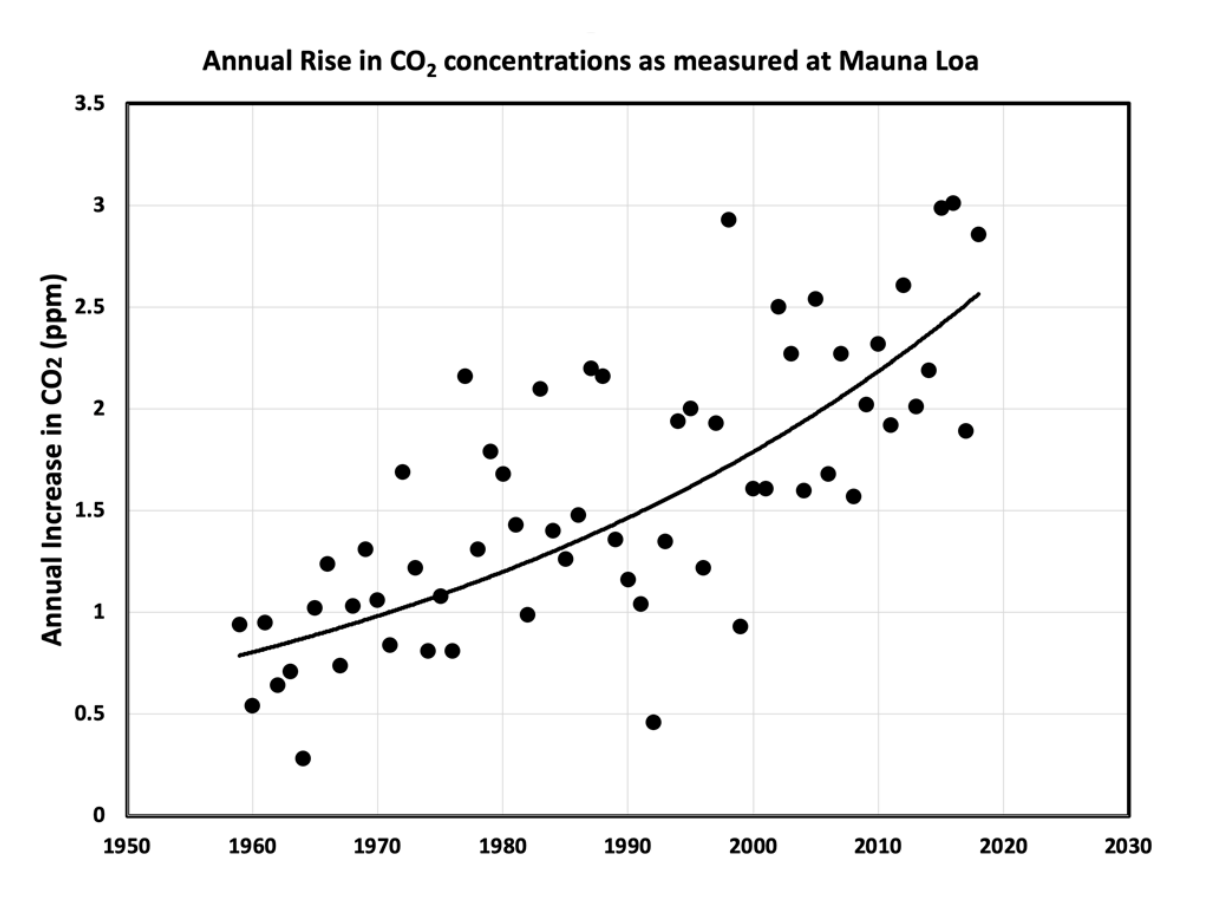

Figure 1. Data collected from observation stations show how noticeably atmospheric CO2 concentrations have risen over the past several decades. (Data compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association; figure by Klaus S. Lackner.)

Morton, E.V. (2020). Reframing the Climate Change Problem: Evaluating the Political, Technological, and Ethical Management of Carbon Dioxide Emissions in the United States. Ph.D. thesis, Arizona State University.

CO2 concentrations are higher today than they have been at any point in the last 3 million years. The contribution of human activity is causing CO2 emissions to rise at an unprecedented rate — approximately 2% per year for the past several decades (Figure 1) — a rate that far outpaces the rate at which the natural world can adapt and adjust. A monumental global effort is needed to reduce CO2 emissions from human activity. But even this is not enough. Because CO2 can persist in the atmosphere for hundreds or thousands of years, CO2 already emitted will continue to have climate impacts for at least the next 1,000 years. Keeping the impacts of climate change to tolerable levels requires not only a suite of actions to reduce future CO2 emissions, but also implementation of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) strategies to mitigate the damage we have already done.

The IPCC defines CDR as “anthropogenic activities removing CO2 from the atmosphere and durably storing it in geological, terrestrial, or ocean reservoirs, or in products.” While becoming more energy efficient can reduce emissions and using renewable energy causes zero emissions, only CDR can achieve the “net negative” emissions needed to help restore climate stability.

Five companies around the world — two of which are based in the United States — have already begun commercializing a particular CDR technology called direct air capture. Climeworks is the most advanced company, and can already remove 900 tons of atmospheric CO2 per year at its plant in Switzerland. Though these companies have demonstrated that CDR technologies like direct air capture work, costs need to come down and capacity needs to expand for CDR to remove meaningful levels of past emissions from the atmosphere.

Thankfully, the Energy Act of 2020, a subsection of the 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act, was passed into law in December 2020. This act creates a carbon removal research, development, and demonstration program within the Department of Energy. It also establishes a prize competition for pre-commercial and commercial applications of direct air capture technologies, provides grants for direct air capture and storage test centers, and creates a CDR task force.

The CDR task force will be led by the Secretary of Energy and include the heads of any other relevant federal agencies chosen by the Secretary. The task force is mandated to write a report that includes an estimate of how much excess CO2 needs to be removed from the atmosphere by 2050 to achieve net zero emissions, an inventory and evaluation of CDR approaches, and recommendations for policy tools that the U.S. government can use to meet the removal estimation and advance CDR deployment. This report will be used to advise the Secretary of Energy on next steps for CDR development and will be submitted to the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and the House of Representatives Committees on Energy and Commerce and Science, Space, and Technology.

The Biden administration has clearly shown its commitment to combating climate change by rejoining the Paris Agreement and signing several Executive Orders that take a whole-of-government approach to the climate crisis. The Energy Act complements these actions by advancing development and demonstration of CDR. However, the Energy Act does not address CDR governance, i.e., the policy tools necessary to efficiently and ethically steward CDR implementation. A proactive governance strategy is needed to ensure that CDR is used to repair past damage and support communities that have been disproportionately harmed by climate change — not as an excuse for the fossil-fuel industry and other major contributors to the climate crisis to continue dumping harmful greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The CDR task force should therefore leverage the crucial opportunity it has been given to shape future use of CDR by incorporating governance recommendations into its report.

Plan of Action

The Department of Energy’s CDR task force should consider recommending the following options in its final report. Taken together, these recommendations form the basis of a governance framework to ensure that CDR technologies are implemented in a way that most responsibly, equitably, and effectively addresses climate change.

Establish net-zero and net-negative carbon removal targets.

The Energy Act commendably directs the CDR task force to estimate the amount of CO2 that the United States must remove to become net zero by 2050. But the task force should not stop there. The task force should also estimate the amount of CO2 that the United States must remove to limit average global warming to 1.5°C (a target that will require net negative emissions) and estimate what year this goal could feasibly be achieved. Much like the National Ambient Air Quality Standards enforced by the Environmental Protection Agency, there should be a specific amount of CO2 that the United States should work toward removing to enhance environmental quality. This target could be based on how much CO2 the United States has put into the atmosphere to date and how much of that amount the United States should be responsible for removing. Both net-zero and net-negative removal targets should be preserved through legislation to continue progress beyond the Biden administration.

Design a public carbon removal service.

If carbon removal targets become law, the federal government will need to develop an organized way of removing and storing CO2 in order to reach those targets. Therefore, the CDR task force should also consider what it would take to develop a public carbon removal service. Just as waste disposal and sewage infrastructure are public services paid for by those that generate waste, industries would pay for the service of having their past and current CO2 emissions removed and stored securely. Revenue generated from a public carbon removal service could be reinvested into CDR technology, carbon storage facilities, maintenance of CDR infrastructure, environmental justice initiatives, and job creation. As the Biden administration ramps up its American Jobs Plan to modernize the country’s infrastructure, it should consider including carbon removal infrastructure. A public carbon removal service could materially contribute to the goals of expanding clean energy infrastructure and creating jobs in the green economy that the American Jobs Plan aims to achieve.

Planning the design and implementation of a public carbon removal service should be conducted in parallel with CDR technology development. Knowing what CDR technologies will be used may change how prize competitions and grant programs funded by the Energy Act are evaluated and how the CDR task force will prioritize its policy recommendations. The CDR task force should assess the CDR technology landscape and determine which technologies — including mechanical, agricultural, and ocean-based processes — are best suited for inclusion in a public carbon removal service. The assessment should be based on factors such as affordability, availability, and storage permanence. The assessment could also consider results from the research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) program and the prize competitions mandated by the Energy Act when making its determination. The task force should also recommend concrete steps towards getting a public carbon removal service up and running. Steps could include, for instance, establishing public-private partnerships with prize competition winners and other commercialized CDR companies.

Create a national carbon accounting standard.

The Energy Act directs the RD&D program to collaborate with the Environmental Protection Agency to develop an accounting framework to certify how much carbon different techniques can remove and how long that carbon can be stored. This may involve investigating the storage permanence of various carbon storage and utilization options. This may also involve creating a database of storage lifetimes for CDR products and processes and identification of CDR techniques best suited for attaining carbon removal targets. The task force could recommend to the Secretary of Energy that the framework becomes a standard. A national carbon accounting standard will be integral for achieving carbon removal targets and verifying removal through public service described above.

Ensure equity in CDR.

While much of the technical and economic aspects of carbon removal have been (or are being) investigated, questions related to equity remain largely unaddressed. The CDR task force should investigate and recommend policies and actions to ensure that carbon removal does not impose or exacerbate societal inequities, especially for vulnerable communities of color and low-income communities. Recommendations that the task force could explore include:

- Establishing a tax credit for investing in CDR on private land. This credit would be similar to existing credits for installing solar and selling electricity back to the grid. Some or all of proceeds from the credit should go to help communities previously harmed by environmental injustice (i.e., “environmental justice communities”).

- Launching a CDR technology deployment program that gives environmental justice communities a tax credit or other financial benefit for allowing a CDR technology to be deployed in their communities. This “hosting” compensation would be earmarked for local environmental remediation.

- Incentivizing design of CDR technologies that deliver co-benefits. For instance, planting trees not only helps remove carbon from the atmosphere but also creates shade, provides habitat, and helps mitigate urban heat-island effects. Industrial direct air capture plants can be surrounded by greenspace and art to create public parks.

- Interviewing environmental justice communities to understand their needs and how those needs could be met through strategic implementation of CDR.

Include CDR in international climate discussions.

Because CDR is a necessary part of any realistic strategy to keep average global warming to tolerable levels, CDR is a necessary part of future international discussions on climate change. The United States can take the lead by including CDR in its nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement. The U.S. NDC most recently submitted in April 2021 does discuss increasing carbon sequestration through agriculture and oceans but could be even more aggressive by including a broader suite of CDR technologies (e.g., engineered direct air capture) and prioritizing pursuit of carbon-negative solutions. The CDR task force could recommend that the Department of Energy work with the Special Presidential Envoy for Climate and the Department of State Office of Global Change on (1) enhancing the NDC through CDR, and (2) developing climate-negotiation strategies intended to increase the use of CDR globally.

Conclusion

Global climate change has worsened to the point where simply reducing emissions is not enough. Even if all global emissions were to cease today, the climate impacts of the carbon we have dumped into the atmosphere would continue to be felt for centuries to come. The only solution to this problem is to achieve net-negative emissions by dramatically accelerating development and deployment of carbon dioxide removal (CDR). As one of the world’s biggest emitters, the United States has a responsibility to do all it can to tackle the climate crisis. And as one of the world’s technological and geopolitical leaders, the United States is well positioned to rise to the occasion, investing in CDR governance alongside the technical and economic aspects of CDR. The CDR task force can lead in this endeavor by advising the Secretary of Energy on an overall governance strategy and specific policy recommendations to ensure that CDR is used in an aggressive, responsible, and equitable manner.

Doubling the R&D Capacity of the Department of Education

Summary

Congress is actively interested in ensuring that the United States is educating the talent needed to maintain our global economic and national security leadership. A number of proposals being considered by Congress focus on putting the National Science Foundation’s Education division on a doubling path over the next 5-7 years.

This memo recommends that the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) — the R&D agency housed within the Department of Education — be put on the similar doubling path with stepladder increases in authorization levels, and targeted program starts (e.g., an “ARPA” housed at ED) focused on major gaps that have been building for years but made even more evident during the pandemic.

This increased funding for IES should be focused on:

• Establishing New Research Capacity in the form of an [1] “ARPA-like” Transformative Research Program;

• Harnessing Data for Impact through investments in [2] Statewide Longitudinal Data Systems (SLDS), [3] a Learning Observatory, and [4] modernization of the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP);

• Conducting Pathbreaking Data-Driven Research by [5] building a permanent Data Science Unit within IES, [6] increasing funding for special education research; and [7] investing in digital learning platforms as research infrastructure; and

• Building the Education Field for Deployment of What Works by [8] establishing a Center of Learning Excellence for state-level recovery investments in tutoring and more.

Reforming Federal Rules on Corporate-Sponsored Research at Tax-Exempt University Facilities

Improving university/corporate research partnerships is key to advancing U.S. competitiveness. Reform of the IRS rules surrounding corporate sponsored research taking place in university facilities funded by tax-exempt bonds has long been sought by the higher education community and will stimulate more public-private partnerships. With Congress considering new ways to fund research through a new NSF Technology Directorate and the possibility of a large infrastructure package, an opportunity is now open for Congress to address these long-standing reforms in IRS rules.

Challenge and Opportunity

Research partnerships between private companies and universities are critical to U.S. technology competitiveness. China and other countries are creating massive, government-funded research centers in artificial intelligence, robotics, quantum computing, biotechnology, and other critical sectors, threatening our nation’s international technology advantage. The United States has responded with initiatives such as the corporate research and development (R&D) tax credit, the SBIR and STTR programs, Manufacturing USA institutes, and numerous other programs and policies to assist tech development and encourage public-private collaborations. States and cities have mirrored these efforts, helping to build a network of innovation hubs in communities across the nation

The U.S. Innovation and Competition Act recently passed by the Senate is designed to build on this progress. A key provision of the Act is the establishment of a National Science Foundation (NSF) Directorate for Science and Technology that would “identify and develop opportunities to reduce barriers for technology transfer, including intellectual property frameworks between academia and industry, nonprofit entities, and the venture capital communities.”

One such barrier is the suite of “private use” rules surrounding corporate research taking place in university facilities financed with tax-exempt bonds. Tax-exempt bonds are a preferred financing option for university research facilities as they carry lower interest rates and more favorable terms. But the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) prohibition on “private business use“ of facilities financed using tax-exempt bonds have the unfortunate consequence of hamstringing the U.S. research enterprise. Current IRS rules place universities wishing to avoid concerns about sponsoring research from outside organizations to hold the rights to almost all intellectual property (IP) generated within their research facilities, even when the research is sponsored by private corporations. This can lead U.S. corporations wishing to retain IP rights to partner with universities overseas instead of U.S. universities institutions. Small technology companies whose business plans depend on their claim to IP rights may similarly avoid partnerships with universities.

Though the IRS has issued policies that aim to address these problems (e.g., Revenue Procedure 2007-47), such policies are so narrow in scope that most research partnerships between companies and universities are still considered private uses. As a result, universities engaged in cutting-edge, industry-relevant research face an unenviable choice: they must either (i) forego promising partnerships with the many companies unwilling to completely cede claims to IP rights, (ii) dedicate substantial time and administrative resources to track and report all specific instances of corporate-sponsored research occurring in facilities financed by tax-exempt bonds, or (iii) use funding that would otherwise be available for research to finance facilities through taxable bonds.

Forcing this choice upon universities further exacerbates a system of “haves” and “have-nots”. Large and/or well-endowed universities may have the financial resources to avoid relying on tax-exempt financing for research facilities, or to hire sophisticated and expensive legal expertise for help structuring financing in a way that complies with IRS rules. But for many — perhaps most — universities, the more viable solution is to avoid corporate-sponsored research altogether.

Complex federal rules governing intellectual property and private business use are widely acknowledged as an issue. A memo from the Association of American Universities (AAU), which represents the leading research universities in North America, notes that “[m]any universities believe that the remaining [IRS] private use regulations are overly restrictive” and “[limit] their ability to conduct certain cooperative research.” Similarly, the website of the Carnegie Mellon University Office of Sponsored Programs warns:

“While colleges and universities have lobbied the Internal Revenue Service to reconsider its position with respect to sponsored research in bond financed facilities, they have not, as yet, been successful. Consequently, if the University does not receive fair market royalties from the sponsors of sponsored research, it risks having its tax-exempt bonds become taxable, with all of the concomitant consequences.”

At a 2013 hearing on “Improving Technology Transfer at Universities, Research Institute and National Laboratories” before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space and Technology, several university witnesses and members of Congress commented on the complications that federal rules present for cooperative research conducted by universities working in partnership with corporations.

In 2014, Congress introduced H.R. 5829 to amend the Internal Revenue Code to provide an exception from the “business use” test for certain public-private research arrangements, but it did not pass as a stand-alone bill.

In June 2021, the American Council of Education and Association of American Universities released a letter to Congress on behalf of over 20 higher education organizations asking Congress to modernize rules on tax exempt bond financing.

Overly restrictive federal rules may hamstring bipartisan efforts by the new administration and Congress to accelerate tech commercialization and enhance U.S. competitiveness in science and technology (S&T). The recent U.S. Innovation and Competition Act, passed by the Senate, for instance, aims to support public-private partnerships, cross-sectoral innovation hubs, and other multistakeholder initiatives in priority S&T areas. But such initiatives may run afoul of rules on facilities financed by tax-exempt bonds…unless reforms are adopted.

Plan of Action

The administration should implement the following two reforms to clarify and update rules governing use of facilities financed by tax-exempt bonds:

- Eliminate the requirement that universities must retain ownership to all IP generated in university-owned facilities financed by tax-exempt bonds. Instead, universities and corporations should be allowed to negotiate their own terms of IP ownership before entering a research partnership.

- Broaden applicability of IRS safe-harbor provisions. IRS revenue procedures include safe-harbor provisions that exempt “basic research agreements” from restrictions on private business use. The IRS defines basic research as “any original investigation for the advancement of scientific knowledge not having a specific commercial objective.” This definition is too narrow. But especially today, the lines between “basic” and applied research are blurry — and virtually nonexistent when it comes to cutting-edge fields such as digitalization, biosciences, and quantum computing. The IRS should broaden the applicability of its safe-harbor provisions to include all research activities, not just ‘basic research’.

Together, these reforms would support new public-private initiatives by the federal government (such the research hubs funded under the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act); help emerging research universities (including minority-serving institutions such as historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs)) grow their profiles and better compete for talent and resources; and repatriate corporate research to the United States. Moreover — since other countries do not have similarly onerous restrictions on research activities conducted in facilities financed with tax-exempt bonds — these reforms are needed for the U.S. tech economy to remain competitive on an international scale.

These reforms require changes to tax laws, but do not require a direct outlay of federal appropriations. Reforms could be implemented as part of several tech-commercialization legislative packages expected to be considered by this Congress, including the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act or the proposed US Infrastructure bill.

Conclusion

As the Congress and the Administration explore ways to make the U.S. more technologically competitive, ensuring robust university-industry partnerships should be a key factor in any strategy. Reforming the current rules concerning corporate research performed in university facilities needs to be considered, given that the IRS rules have not been updated in over 30 years. The debate over the infrastructure bill or other competitiveness initiatives provides such an opportunity to make these reforms. Now is the time.