Systems Thinking in Climate: Positive Tipping Points Jumpstart Transformational Change

This blog post is the second piece in a periodic series by FAS on systems thinking. The first is on systems thinking in entrepreneurial ecosystems.

News was abuzz two weeks ago with a flurry of celebratory articles showcasing the first-year accomplishments of the Administration’s signature clean energy law, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), on its August 16-anniversary. The stats are impressive. Since the bill’s passage, some 270 new clean energy projects have been announced, with investments totaling some $132 billion, according to a Bank of America analyst report. President Biden, speaking at a White House anniversary event, reported that the legislation has already created 170,000 clean energy jobs and will create some 1.5 million jobs over the next decade, while significantly cutting the nation’s carbon emissions.

The New York Times also headlined an article last week: “The Clean Energy Future Is Arriving Faster Than You Think,” citing that “globally, change is happening at a pace that is surprising even the experts who track it closely.” In addition, the International Energy Agency, which provides analysis to support energy security and the clean energy transition, made its largest ever upward revision to its forecast on renewable capacity expansion. But should this accelerated pace of change that we are seeing really be such a surprise? Or, can rapid acceleration of transformation be predicted, sought after, and planned for?

FAS Senior Associate Alice Wu published a provocative policy memo last week entitled, “Leveraging Positive Tipping Points To Accelerate Decarbonization.” Wu asserts that we can anticipate and drive toward thresholds in decarbonization transitions. A new generation of economic models can enable the analysis of these tipping points and the evaluation of effective policy interventions. But to put this approach front and center will require an active research agenda and a commitment to use this framework to inform policy decisions. If done successfully, a tipping points framework can help forecast multiple different aspects of the decarbonization transition, such as food systems transformation and for ensuring that accelerated transitions happen in a just and equitable manner.

Over the past year, FAS has centralized the concept of positive tipping points as an organizing principle in how we think about systems change in climate and beyond. We are part of a global community of scholars, policymakers, and nonprofit organizations that recognize the potential power in harnessing a positive tipping points framework for policy change. The Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter, Systemiq, and the Food and Land Use Coalition are a few of the leading organizations working to apply this framework in a global context. FAS is diving deep into the U.S. policy landscape, unpacking opportunities with current policy levers (like the IRA) to identify positive tipping points in progress and, hopefully, to build capacity to anticipate and drive toward positive tipping points in the future.

Through a partnership between FAS and Metaculus, a crowd-forecasting platform, a Climate Tipping Points Tournament has provided an opportunity for experienced and novice forecasters alike to dive deep into climate policy questions related to Zero Emissions Vehicles (ZEVs). The goal is to anticipate some of these nonlinear transformation thresholds before they occur and explore the potential impacts of current and future policy levers.

While the tournament is still ongoing, it is already yielding keen insights on when accelerations in systems behavior is likely to occur, on topics that range from the growth of ZEV workforce to the supply chain dynamics for critical minerals needed for ZEV batteries. FAS is planning to publish a series of memos that will seek to turn insights from the tournament into actionable policy recommendations. Future topics planned include: 1) ZEV subsidies; 2) public vs. private charging stations; sodium ion battery research and development; and 4) ZEV battery recycling and the circular economy.

Going forward, FAS will continue to elevate the concept of positive tipping points in the climate space and beyond. We believe that if scientists and policymakers work together toward operationalizing this framework, positive tipping points can move quickly from the realm of the theoretical to become an instrument of policy design that enables decision makers to craft laws and executive action that promotes systems change toward the beneficial transformations we are seeking.

Systems Thinking In Entrepreneurship Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems”

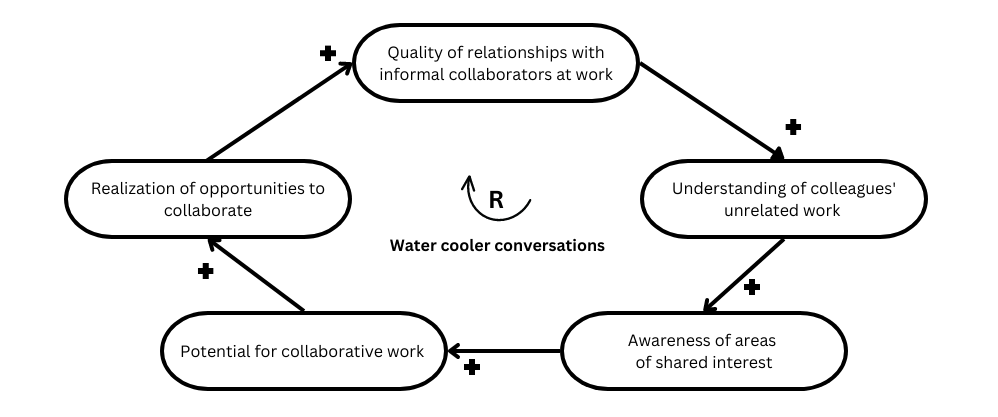

As someone who works remotely and travels quite a long way to be with my colleagues, I really value my “water cooler moments” in the FAS office, when I have them. The idea for this series came from one such moment, when Josh Schoop and I were sharing a sparkling water break. Systems thinking, we realized, is a through line in many parts of our work, and part of the mental model that we share that leads to effective change making in complex, adaptive systems. In the geekiest possible terms:

Systems analysis had been a feature of Josh’s dissertation, while I had had an opportunity to study a slightly more “quant” version of the same concepts under John Sterman at MIT Sloan, through my System Dynamics coursework. The more we thought about it, systems thinking and system dynamics were present across the team at FAS–from our brilliant colleague Alice Wu, who had recently given a presentation on Tipping Points, to folks who had studied the topic more formally as engineers, or as students at Michigan and MIT. This led to the first meeting of our FAS “Systems Thinking Caucus” and inspired a series of blog posts which intend to make this philosophical through-line more clear. This is just the first, and describes how and why systems thinking is so important in the context of entrepreneurship policy, and how systems modeling can help us better understand which policies are effective.

The first time I heard someone described as an “ecosystem builder,” I am pretty sure that my eyes rolled involuntarily. The entrepreneurial community, which I have spent my career supporting, building, and growing, has been my professional home for the last 15 years. I came to this work not out of academia, but out of experience as an entrepreneur and leader of entrepreneur support programs. As a result, I’ve always taken a pragmatic approach to my work, and avoided (even derided) buzzwords that make it harder to communicate about our priorities and goals. In the world of tech startups, in which so much of my work has roots, buzzwords from “MVP” to “traction” are almost a compulsion. Calling a community an “ecosystem” seemed no different to me, and totally unnecessary.

And yet, over the years, I’ve come to tolerate, understand, and eventually embrace “ecosystems.” Not because it comes naturally, and not because it’s the easiest word to understand, but because it’s the most accurate descriptor of my experience and the dynamics I’ve witnessed first-hand.

So what, exactly, are innovation ecosystems?

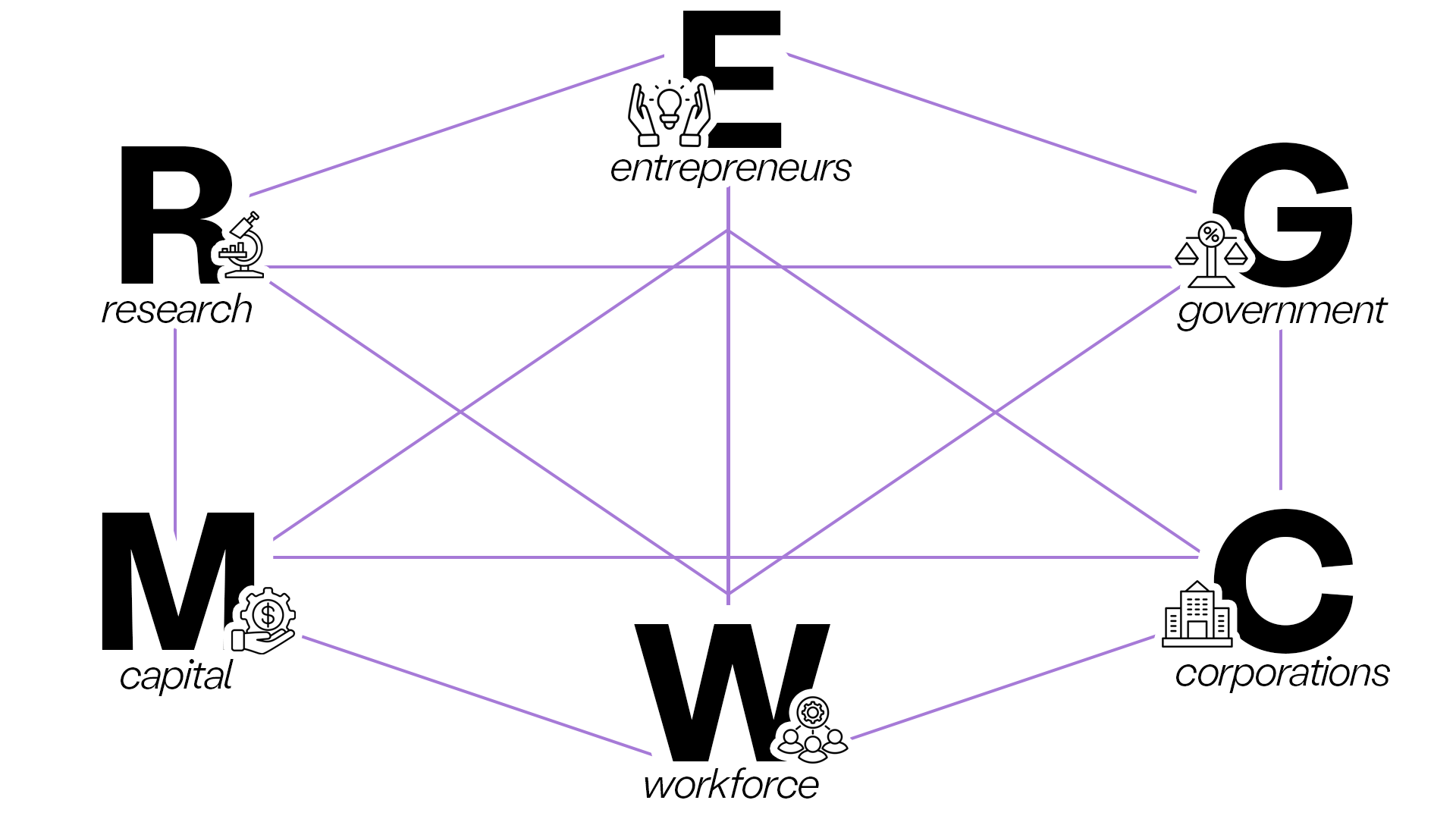

My understanding of innovation ecosystems is grounded first in the experience of navigating one in my hometown of Kansas City–first, as a newly minted entrepreneur, desperately seeking help understanding how to do taxes, and later as a leader of an entrepreneur support organization (ESO), a philanthropic funder, and most recently, as an angel investor. It’s also informed by the academic work of Dr. Fiona Murray and Dr. Phil Budden. The first time that I saw their stakeholder model of innovation ecosystems, it crystallized what I had learned through 15 years of trial-and-error into a simple framework. It resonated fully with what I had seen firsthand as an entrepreneur desperate for help and advice–that innovation ecosystems are fundamentally made up of people and institutions that generally fall into the same categories: entrepreneurs, risk capital, universities, government, or corporations.

Over time–both as a student and as an ecosystem builder, I came to see the complexity embedded in this seemingly simple idea and evolved my view. Today, I amend that model of innovation ecosystems to, essentially, split universities into two stakeholder groups: research institutions and workforce development. I take this view because, though not every secondary institution is a world-leading research university like MIT, smaller and less research-focused colleges and universities play important roles in an innovation ecosystem. Where is the room for institutions like community colleges, workforce development boards, or even libraries in a discussion that is dominated by the need to commercialize federally-funded research? Two goals–the production of human capital and the production of intellectual property–can also sometimes be in tension in larger universities, and thus are usually represented by different people with different ambitions and incentives. The concerns of a tech transfer office leader are very different from those of a professor in an engineering or business school, though they work for the same institution and may share the same overarching aspirations for a community. Splitting the university stakeholder into two different stakeholder groups makes the most sense to me–but the rest of the stakeholder model comes directly from Dr. Murray and Dr. Budden.

One important consideration in thinking about innovation ecosystems is that boundaries really do matter. Innovation ecosystems are characterized by the cooperation and coordination of these stakeholder groups–but not everything these stakeholders do is germane to their participation in the ecosystem, even when it’s relevant to the industry that the group is trying to build or support.

As an example, imagine a community that is working to build a biotech innovation ecosystem. Does the relocation of a new biotech company to the area meaningfully improve the ecosystem? Well, that depends! It might, if that company actively engages in efforts to build the ecosystem say, by directing an executive to serve on the board of an ecosystem building nonprofit, helping to inform workforce development programs relevant to their talent needs, instructing their internal VC to attend the local accelerator’s demo day, offering dormant lab space in their core facility to a cash-strapped startup at cost, or engaging in sponsored research with the local university. Relocation of the company may not improve the ecosystem if they simply happen to be working in the targeted industry and receive a relocation tax credit. In short, by itself, shared work between two stakeholders on an industry theme does not constitute ecosystem building. That shared work must advance a vision that is shared by all of the stakeholders that are core to the work.

Who are the stakeholders in innovation ecosystems?

Innovation ecosystems are fundamentally made up of six different kinds of stakeholders, who, ideally, work together to advance a shared vision grounded in a desire to make the entrepreneurial experience easier. One of the mistakes I often see in efforts to build innovation ecosystems is an imbalance or an absence of a critical stakeholder group. Building innovation ecosystems is not just about involving many people (though it helps), it’s about involving people that represent different institutions and can help influence those institutions to deploy resources in support of a common effort. Ensuring stakeholder engagement is not a passive box-checking activity, but an active resource-gathering one.

An innovation ecosystem in which one or more stakeholders is absent will likely struggle to make an impact. Entrepreneurs with no access to capital don’t go very far, nor do economic development efforts without government buy-in, or a workforce training program without employers.

In the context of today’s bevvy of federal innovation grant opportunities with 60-day deadlines, it can be tempting to “go to war with the army you have” instead of prioritizing efforts to build relationships with new corporate partners or VCs. But how would you feel if you were “invited” to do a lot of work and deploy your limited resources to advance a plan that you had no hand in developing? Ecosystem efforts that invest time in building relationships and trust early will benefit from their coordination, regardless of federal funding.

These six stakeholder groups are listed in Figure 2 and include:

- Entrepreneurs – Those who have started and are working to start new companies, including informal entrepreneurs, sole proprietors, small businesses, tech startups, university researchers considering or pursuing tech transfer, deep tech startups, manufacturing firms, service firms, and non-profit organizations that convene them and are accountable to them.

- Government – Public entities of all levels and branches, including, local, state, and federal government agencies and officials, as well as pseudo-governmental organizations, Councils of Governments (COGS) or Economic Development Districts (EDDs), economic development organizations and Chambers of Commerce (which may alternately be considered part of the corporations bullet, depending on their accountability structure), and public-private partnerships.

- Corporations – Large and established companies in a region that are relevant in their capacity as major employers, large-scale purchasers, pilot customers, sponsors of research, and potential strategic investors and acquirers of technology and innovation-driven companies. Corporations might also act in the classical definition of cluster development, providing fractional access to advanced equipment or capabilities that the scale of their cap-ex facilitates, to improve access to such facilities for smaller or newer companies with fewer assets to fund such investments.

- Workforce Development – The programs and capabilities in a community that produce a base of employees with the specific skills and competencies to support both growing and established companies, including K-12 systems and districts, educators, non-degree credential programs, professional training programs or job pipelines, skills-based development communities and meetups, regional workforce partnerships, community colleges, and colleges and universities of all kinds.

- Capital – Providers of private capital that supports the creation of commercial value in exchange for a return on investment, including venture capital, angel investors, angel networks, private equity investors, limited partners or institutional investors, as well as community banks, CDFIs, CDCs, other non-bank loan funds, fintechs, and providers of alternative financing such as factoring or revenue/royalty-based financing.

- Research Institutions – Organizations which conduct the basic and applied research from which deep tech businesses might be formed and begin the process of commercializing that research, including research universities and affiliated centers and institutes, research and teaching hospitals, private research institutions, national labs, Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs), and Focused Research Organizations.

In the context of regional, place-based innovation clusters (including tech hubs), this stakeholder model is a tool that can help a burgeoning coalition both assess the quality and capacity of their ecosystem in relation to a specific technology area and provide a guide to prompt broad convening activities. From the standpoint of a government funder of innovation ecosystems, this model can be used as a foundation for conducting due diligence on the breadth and engagement of emerging coalitions. It can also be used to help articulate the shortcomings of a given community’s engagements, to highlight ecosystem strengths and weaknesses, and to design support and communities of practice that convene stakeholder groups across communities.

What about entrepreneur support organizations (ESO)? What about philanthropy? Where do they fit into the model?

When I introduce this model to other ecosystem builders, one of the most common questions I get is, “where do ESOs fit in?” Most ESOs like to think of themselves as aligned with entrepreneurs, but that merits a few cautionary notes. First, the critical question you should ask to figure out where an ESO, a Chamber or any other shape-shifting organization fits into this model is, “what is their incentive structure?” That is to say, the most important thing is to understand to whom an organization is accountable. When I worked for the Enterprise Center in Johnson County, despite the fact that I would have sworn up-and-down that I belonged in the “E” category with the entrepreneurs I served, our sustaining funding was provided by the county government. My core incentive was to protect the interests of a political subdivision of the metro area, and a perceived failure to do that would have likely resulted in our organization’s funding being cut (or at least, in my being fired from it). That means that I truly was a “G,” or a government stakeholder. So, intrepid ESO leader, unless the people that fund, hire, and fire you are majority entrepreneurs, you’re likely not an “E.”

The second danger of assuming that ESOs are, in fact, entrepreneurs, is that it often leads to a lack of actual entrepreneurs in the conversation. ESOs stand in for entrepreneurs who are too busy to make it to the meeting. But the reality is that even the most well-meaning ESOs have a different incentive structure than entrepreneurs–meaning that it is very difficult for them to naturally represent the same views. Take for instance, a community survey of entrepreneurs that finds that entrepreneurs see “access to capital” as the primary barrier to their growth in a given community. In my experience, ESOs generally take that somewhat literally, and begin efforts to raise investment funds. Entrepreneurs, on the other hand who simply meant “I need more money,” might see many pathways to getting it, including by landing a big customer. (After all, revenue is the cheapest form of cash.) This often leads ESOs to prioritize problems that match their closest capabilities, or the initiatives most likely to be funded by government or philanthropic grants. Having entrepreneurs at the table directly is critically important, because they see the hairiest and most difficult problems first–and those are precisely the problems it take a big group of stakeholders to solve.

Finally, I have seen folks ask a number of times where philanthropy fits into the model. The reality is that I’m not sure. My initial reaction is that most philanthropic organizations have a very clear strategic reason for funding work happening in ecosystems–their theory of change should make it clear which stakeholder views they represent. For example, a community foundation might act like a “government” stakeholder, while a funder of anti-poverty work who sees workforce development as part or their theory of change is quite clearly part of the “W” group. But not every philanthropy has such a clear view, and in some cases, I think philanthropic funders, especially those in small communities, can think of themselves as a “shadow stakeholder,” standing in for different viewpoints that are missing in a conversation. Finally, philanthropy might play a critical and underappreciated role as a “platform creator.” That is, they might seed the conversation about innovation ecosystems in a community, convene stakeholders for the first time, or fund activities that enable stakeholders to work and learn together, such as planning retreats, learning journeys, or simply buying the coffee or providing the conference room for a recurring meeting. Finally, and especially right now, philanthropy has an opportunity to act as an “accelerant,” supporting communities by offering the matching funds that are so critical to their success in leveraging federal funds.

Why is “ecosystem” the right word?

Innovation ecosystems, like natural systems, are both complex and adaptive. They are complex because they are systems of systems. Each stakeholder in an innovation ecosystem is not just one person, but a system of people and institutions with goals, histories, cultures, and personalities. Not surprisingly, these systems of systems are adaptive, because they are highly connected and thus produce unpredictable, ungovernable performance. It is very, very difficult to predict what will happen in a complex system, and most experts in fields like system dynamics will tell you that a model is never truly finished, it is just “bounded.” In fact, the way that the quality of a systems model is usually judged is based on how closely it maps to a reference mode of output in the past. This means that the best way to tell whether your systems model is any good is to give it “past” inputs, run it, and see how closely it compares to what actually happened. If I believe that job creation is dependent on inflation, the unemployment rate, availability of venture capital, and the number of computer science majors graduating from a local university, one way to test if that is truly the case is to input those numbers over the past 20 years, run a simulation of how many jobs would be created, according to the equations in my model, and seeing how closely that maps to the actual number of jobs created in my community over the same time period. If the line maps closely, you’ve got a good model. If it’s very different, try again, with more or different variables. It’s quite easy to see how this trial-and-error based process can end up with an infinitely expanding equation of increasing complexity, which is why the “bounds” of the model are important.

Finally, complex, adaptive systems are, as my friend and George Mason University Professor Dr. Phil Auerswald says, “self-organizing and robust to intervention”. That is to say, it is nearly impossible to predict a linear outcome (or whether there will be any outcome at all) based on just a couple of variables. This means that the simple equation(money in = jobs out) is wrong. To be better able to understand the impact of a complex, adaptive system requires mapping the whole system and understanding how many different variables change cyclically and in relation to each other over a long period of time. It also requires understanding the stochastic nature of each variable. That is a very math-y way of saying it requires understanding the precise way in which each variable is unpredictable, or the shape of its bell-curve.

All of this is to say that understanding and evaluation of innovation ecosystems requires an entirely different approach than the linear jobs created = companies started * Moretti multiplier assumptions of the past.

So how do you know if ecosystems are growing or succeeding if the number of jobs created doesn’t matter?

The point of injecting complexity thinking into our view of ecosystems is not to create a sense of hopelessness. Complex things can be understood–they are not inherently chaotic. But trying to understand these ecosystems through traditional outputs and outcomes is not the right approach since those outputs and outcomes are so unpredictable in the context of a complex system. We need to think differently about what and how we measure to demonstrate success. The simplest and most reliable thing to measure in this situation then becomes the capacities of the stakeholders themselves, and the richness or quality of the connections between them. This is a topic we’ll dive into further in future posts.