Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan

Any time a US federal agency proposes a major action that “has the potential to cause significant effects on the natural or human environment,” they must complete an Environmental Impact Statement, or EIS. An EIS typically addresses potential disruptions to water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other factors in great detail––meaning that one can usually learn a lot about the scale and scope of a federal program by examining its Environmental Impact Statement.

What does all this have to do with nuclear weapons, you ask?

Well, given that the Air Force’s current plan to modernize its intercontinental ballistic missile force involves upgrading hundreds of underground and aboveground facilities, it appears that these actions have been deemed sufficiently “disruptive” to trigger the production of an EIS.

To that end, the Air Force recently issued a Notice of Intent to begin the EIS process for its Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program––the official name of the ICBM replacement program. Usually, this notice is coupled with the announcement of open public hearings, where locals can register questions or complaints with the scope of the program. These hearings can be influential; in the early 1980s, tremendous public opposition during the EIS hearings in Nevada and Utah ultimately contributed to the cancellation of the mobile MX missile concept. Unfortunately, in-person EIS hearings for the GBSD have been cancelled due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic; however, they’ve been replaced with something that might be even better.

The Air Force has substituted its in-person meetings for an uncharacteristically helpful and well-designed website––gbsdeis.com––where people can go to submit comments for EIS consideration (before November 13th!). But aside from the website being just a place for civic engagement and cute animal photos, it is also a wonderful repository for juicy––and sometimes new––details about the GBSD program itself.

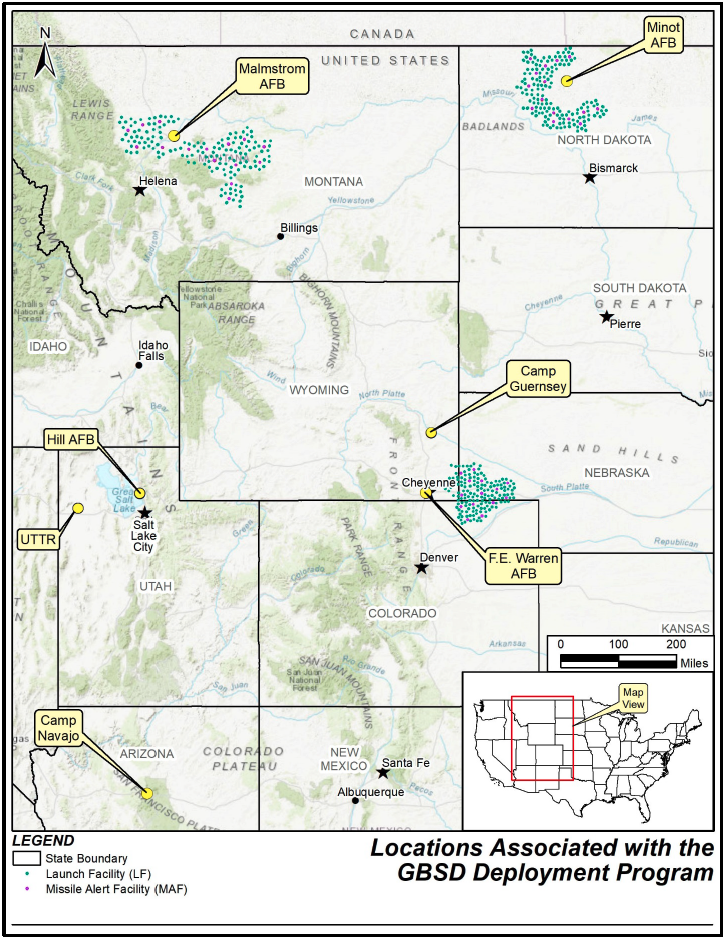

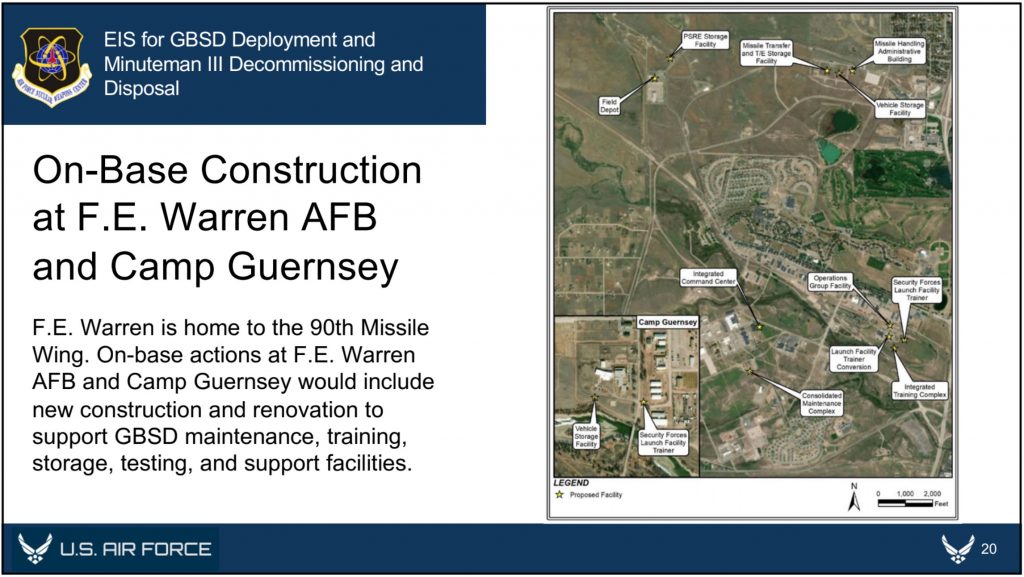

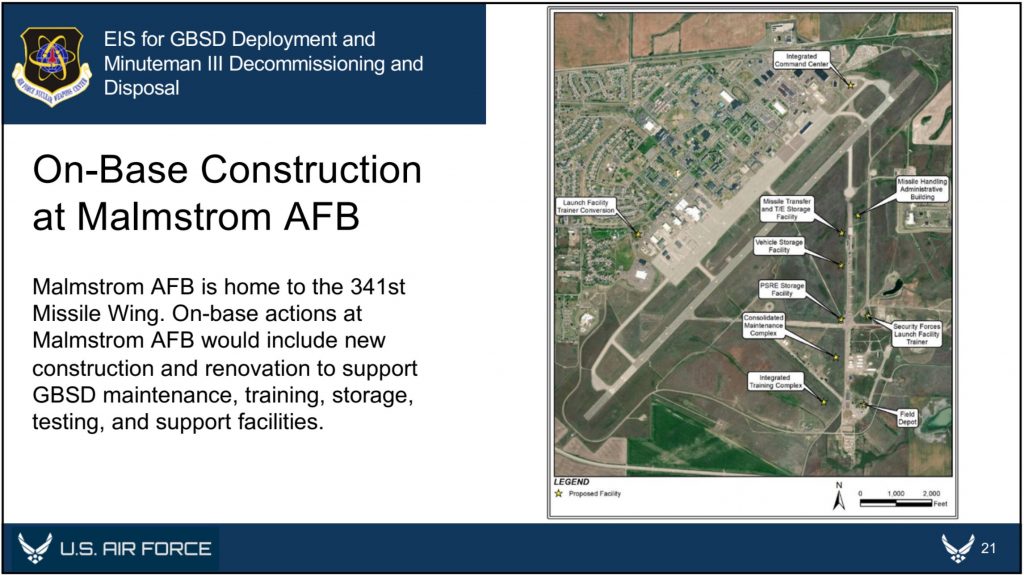

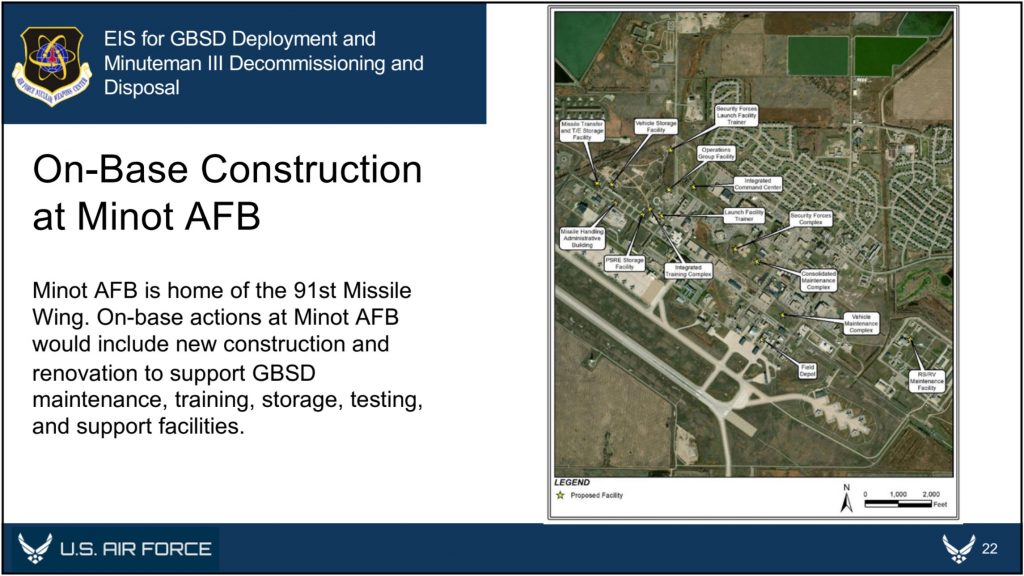

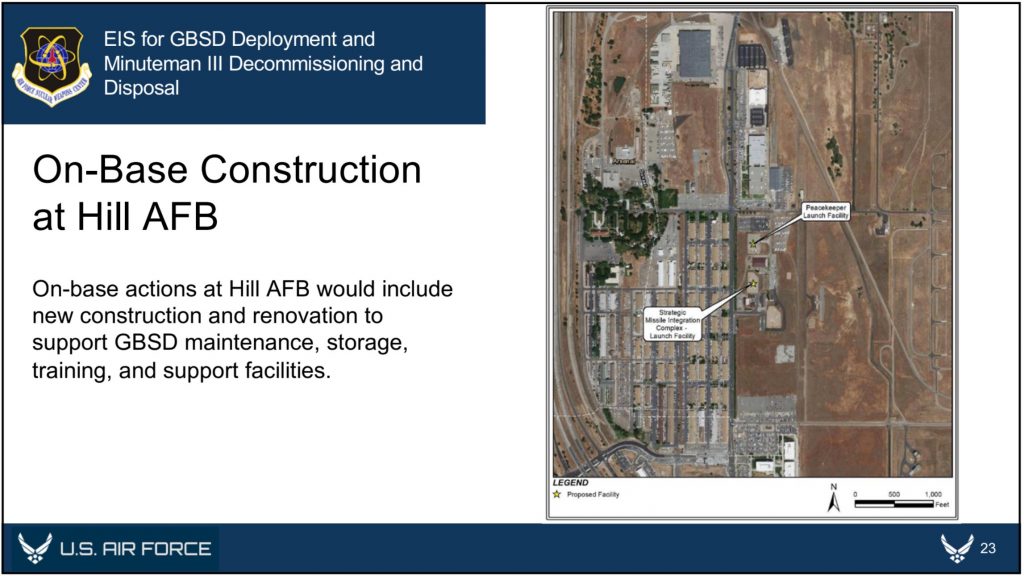

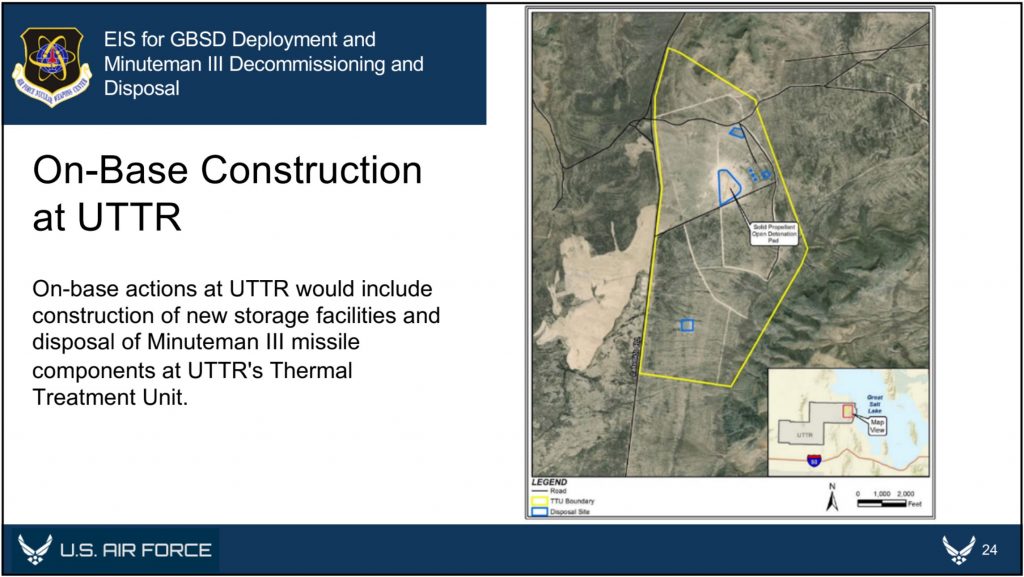

The website includes detailed overviews of the GBSD-related work that will take place at the three deployment bases––F.E. Warren (located in Wyoming, but responsible for silos in Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska), Malmstrom (Montana), and Minot (North Dakota)––plus Hill Air Force Base in Utah (where maintenance and sustainment operations will take place), the Utah Test and Training Range (where missile storage, decommissioning, and disposal activities will take place), Camp Navajo in Arizona (where rocket boosters and motors will be stored), and Camp Guernsey in Wyoming (where additional training operations will take place).

Taking a closer look at these overviews offers some expanded details about where, when, and for how long GBSD-related construction will be taking place at each location.

For example, previous reporting seemed to indicate that all 450 Minuteman Launch Facilities (which contain the silos themselves) and “up to 45” Missile Alert Facilities (each of which consists of a buried and hardened Launch Control Center and associated above- or below-ground support buildings) would need to be upgraded to accommodate the GBSD. However, the GBSD EIS documents now seem to indicate that while all 450 Launch Facilities will be upgraded as expected, only eight of the 15 Missile Alert Facilities (MAF) per missile field would be “made like new,” while the remainder would be “dismantled and the real property would be disposed of.”

Currently, each Missile Alert Facility is responsible for a group of 10 Launch Facilities; however, the decision to only upgrade eight MAFs per wing––while dismantling the rest––could indicate that each MAF could be responsible for up to 18 or 19 separate Launch Facilities once GBSD becomes operational. If this is true, then this near-doubling of each MAF’s responsibilities could have implications for the future vulnerability of the ICBM force’s command and control systems.

The GBSD EIS website also offers a prospective construction timeline for these proposed upgrades. The website notes that it will take seven months to modernize each Launch Facility, and 12 months to modernize each Missile Alert Facility. Once construction begins, which could be as early as 2023, the Air Force has a very tight schedule in order to fully deploy the GBSD by 2036: they have to finish converting one Launch Facility per week for nine years. It is expected that construction and deployment will begin at F.E. Warren between 2023 and 2031, followed by Malmstrom between 2025 and 2033, and finally Minot between 2027 and 2036.

Although it is still unclear exactly what the new Missile Alert Facilities and Launch Facilities will look like, the EIS documents helpfully offer some glimpses of the GBSD-related construction that will take place at each of the three Air Force bases over the coming years.

In addition to the temporary workforce housing camps and construction staging areas that will be established for each missile wing, each base is expected to receive several new training, storage, and maintenance facilities. With a single exception––the construction of a new reentry system and reentry vehicle maintenance facility at Minot––all of the new facilities will be built outside of the existing Weapons Storage Areas, likely because these areas are expected to be replaced as well. As we reported in September, construction has already begun at F.E. Warren on a new underground Weapons Generation Facility to replace the existing Weapons Storage Area, and it is expected that similar upgrades are planned for the other ICBM bases.

Finally, the EIS documents also provide an overview of how and where Minuteman III disposal activities will take place. Upon removal from their silos, the Minutemen IIIs will be transported to their respective hosting bases––F.E. Warren, Malmstrom, or Minot––for temporary storage. They will then be transported to Hill Air Force Base, the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), or Camp Najavo, in Arizona. It is expected that the majority of the rocket motors will be stored at either Hill AFB or UTTR until their eventual destruction at UTTR, while non-motor components will be demilitarized and disposed of at Hill AFB. To that end, five new storage igloos and 11 new storage igloos will be constructed at Hill AFB and UTTR, respectively. If any rocket motors are stored at Camp Navajo, they will utilize existing storage facilities.

After the completion of public scoping on November 13th (during which anyone can submit comments to the Air Force via Google Form), the next public milestone for the GBSD’s EIS process will occur in spring 2022, when the Air Force will solicit public comments for their Draft EIS. When that draft is released, we should learn even more about the GBSD program, and particularly about how it impacts––and is impacted by––the surrounding environment. These particular aspects of the program are growing in significance, as it is becoming increasingly clear that the US nuclear deterrent––and particularly the ICBM fleet deployed across the Midwest––is uniquely vulnerable to climate catastrophe. Given that the GBSD program is expected to cost nearly $264 billion through 2075, Congress should reconsider whether it is an appropriate use of public funds to recapitalize on elements of the US nuclear arsenal that could ultimately be rendered ineffective by climate change.

Additional background information:

- United States nuclear forces, 2020

-

Construction of New Underground Nuclear Warhead Facility At Warren AFB

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Image sources: Air Force Global Strike Command. 2020. “Environmental Impact Statement for the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent Deployment and Minuteman III Decommissioning and Disposal: Public Scoping Materials.”

The Evolution of the Senate Arms Control Observer Group

In March 2013, the Senate voted down an amendment offered by Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) to cut $700,000 from their budget that was set-aside for the National Security Working Group (NSWG). What many did not realize at the time was that this relatively small and obscure proposed cut would have eliminated one of the last traces of the bipartisan Congressional approach to debating arms control.

The NSWG first began as the Arms Control Observer Group, which helped to build support for arms control in the Senate. In recent years, there have been calls from both Democrats and Republicans to revive the Observer Group, but very little analysis of the role it played. Its history illustrates the stark contrast in the Senate’s attitude and approach to arms control issues during the mid- to late 1980s compared with the divide that exists today between the two parties.

The Arms Control Observer Group

The Arms Control Observer Group was first formed in 1985. At the time, the United States was engaged in talks with the Soviet Union on the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty. To generate support for ongoing negotiations, Majority Leader Senator Bob Dole (R-KS), and Minority Leader Senator Robert Byrd (D-WV), with the endorsement of President Ronald Reagan, created the bipartisan Arms Control Observer Group. The Observer Group consisted of twelve senators, with four senators, two from each party, serving as co-chairs and created an official role for senators to join U.S. delegations as they negotiated arms control treaties. As observers, its members had two duties: to consult with and advise U.S. arms control negotiating teams, and “to monitor and report to the Senate on the progress and development of negotiations.”

During meetings with U.S. State Department negotiators, senators were able to present their views, ask questions, and even engage in candid and confidential exchanges of ideas and information. Senators were also allowed to meet with members of the Soviet delegations on an “informal” basis. The Observer Group believed that the “interplay of ideas” would assist negotiators and, if negotiations failed, the members would help their fellow senators explain the reasons why to the American public.

The Observer Group served a number of purposes. First, it was intended to supplement the activities of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Senator Byrd argued that the process that existed up until that point—where the Foreign Relations Committee became experts on treaties and the full Senate only began to understand the issues after the negotiation—was not functioning properly. Its creators argued, “the full Senate has focused its attention in the past only sporadically on the vital aspects of arms control negotiations, usually developing a knowledge and understanding of the issues being negotiated after the fact…the result of this fitful process has been generally unsatisfactory in recent years.” During the previous decade, the Executive Branch had failed to garner enough Senate support for several arms control initiatives: the Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty of 1976, the Threshold Test Ban Treaty of 1974, and the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II) of 1979, none of which were ratified by the United States. Although there had been previous attempts to involve senators in arms control negotiations, the Observer group provided “more regular and systematic involvement” from the full Senate long before a vote took place.

The formation of the Observer Group publicly demonstrated the important role of arms control in national security matters. The resolution that created the group states that senators have the “obligation to become as knowledgeable as possible concerning the salient issues, which are being addressed in the context of the negotiating process. Any accord with the Soviet Union to control or reduce our strategic weapons carries considerable weight for our nation.” According to Senator Sam Nunn (D-GA), a founding member of the Observer Group, “the goal [was] to have the Senate fulfill both halves of its constitutional responsibilities, not only the consent half—that’s what we’ve been looking to primarily in the past—but also the advice half.”

Additionally, the Observer Group helped develop institutional knowledge and expertise on arms control within the Senate. The Group’s founding members stated that they believed it was necessary to become “completely conversant” in issues related to treaty negotiations and that such knowledge was “critical” to the Senate’s understanding of the issues involved. To achieve that goal, they held regular behind closed-door briefings on negotiations for senators and their staff and some staffers were able to review related classified materials. Observer Group members were conversant in issues related to previous arms control treaties, missile defense, the connection between strategic offense and defense, and treaty compliance.

Above all, the Observer Group was intended to help build bipartisan support for President Reagan’s arms control initiatives. The group was seen as a mediating body. When it was formed, Senators Dole and Byrd co-authored a resolution stating that the Observer Group was part of “an ongoing process to reestablish a bipartisan spirit in this body’s consideration of vital national security and foreign policy issues.” Senator Richard Lugar (R-IN), who was one of the original members of the Observer Group, agreed by affirming, “The observer group is tremendously important to forming a consensus on which ratification might occur.” The Group’s 1985 report to Congress endorsed “the broad bipartisan support of the Senate for the Administration’s arms control efforts…determination to be as patient as necessary to achieve a sound agreement…the seriousness with which the Senate, including the Observer group intends to fulfill its constitutionally-mandated role in the treaty-making process.” This opinion was also shared by the Reagan administration. In a letter to Senators Dole and Byrd, Secretary of State George Shultz stated that he thought the Observer Group would help facilitate unity on arms control.

It is difficult to demonstrate the extent of its influence as the years the Observer Group was most active were also the years in which arms control was seen by both parties as a vital part of U.S. policy. The success of these initiatives was clearly not solely due to the Observer Group, but it did play a role. Every one of the original Group’s members voted in favor of the INF Treaty in 1988, which passed 93-5. Similarly, all of the senators within the Group voted in favor of ratifying the 1992 START Treaty, which passed 93-6.

The National Security Working Group

Towards the end of the 1990s, the Senate’s attitude towards arms control changed. Negotiations between the United States and Russia on a legally binding nuclear reduction treaty had stalled. The Senate had voted down the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Reflecting this changing point of view, in 1999, Senator Trent Lott (R-MS), wanted to further diminish the Senate’s focus and expertise on arms control issues. He proposed an amendment that expanded the Observer Group’s purview to include observing talks related to missile defense and export controls and renamed it the National Security Working Group. For nearly a decade during the George W. Bush administration, which pursued relatively little in terms of legally binding arms control agreements, the NSWG was relatively dormant.

This changed in 2009 under the Obama administration when the Executive Branch started briefing senators about the ongoing New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) negotiations. From July 6, 2009, when President Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed an agreement to reduce American and Russian nuclear arsenals, to April 10, 2010, when they signed the negotiated treaty, the NSWG was revived in order to give senators a role in observing the negotiation process. During this ten-month period, the NSWG began meeting again. The meetings were open to members of the Armed Services and Foreign Relations committees and were well attended, with roughly 50 percent attendance from those who were invited. Senators who participated in the Working Group knew it was a serious matter and paid attention to it. As a result of their attendance, they left meetings better informed on issues related to arms control.

Throughout the course of Senate deliberation of New START, Senator Jon Kyl (R-AZ) served as the Republican Party’s key interlocutor with Democrats. Unlike his predecessors in the Observer Group, Senator Kyl did not see the Working Group as a vehicle for bipartisan cooperation and consensus building. Senator Kyl used his position as the chief negotiator to disrupt the Obama administration’s legislative agenda on arms control.

Senator Kyl used issues peripheral to the treaty, such as missile defense and modernization of the nuclear stockpile, to “slow roll” the legislative process and prevent the administration from pursuing the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, which he ardently opposed.1 According to one account, Senator Kyl “was not using the Working Group. It was just a tool to stop the policy. There wasn’t a getting to yes option. It wasn’t there to get to yes. If the members of the group aren’t inclined to get to yes, then the mechanism won’t get them there.” Further, he “came prepared to ask tough questions, not just to listen and probe. He was there to look for chinks in the arms and attack in front of his colleagues. He wanted his colleagues to see it.”

In an effort to prevent Senator Kyl from disrupting meetings, Senate staff made the NSWG open to all members of the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services Committees. They also made sure that senior Democratic leadership was present for all of the NSWG meetings. Either Senator John Kerry (D-MA) or Carl Levin (D-MI) served as Chair and were both prepared to answer all questions and concerns.

Despite this impediment, senators still appear to have found the Working Group useful. Senator Levin, Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, said the NSWG provided an opportunity to bring senators in at the beginning of the negotiation process, and “through the group” there were “many opportunities to learn of the progress and details of negotiations and to provide our advice and views to the administration throughout the process.” He praised the NSWG’s work, arguing that it was a “key” part of the treaty ratification process because it allowed senators to begin meeting with the administration “early in the process of negotiation” before New START was finalized. He said that during the New START process, “members of the National Security Working Group asked a great number of questions, received answers at a number of meetings, stayed abreast of the negotiation details, and provided advice to the administration.” Finally, he added that, through the NSWG, the administration had the opportunity to respond to senators’ questions and concerns, which helped to avoid problems during the Senate’s consideration of the treaty.

The Senate was less supportive of arms control this time around. Even with senators actively involved in the NSWG, only 13 Republicans ended up supporting the treaty. Of those 13, only four Republicans were members of the Working Group (Senators Lugar, Corker, Voinovich, and Cochran). Among those four, only Senator Lugar was a particularly strong advocate for the treaty.

At best, the Working Group had a mixed track record and certainly did not have the same kind of success as the Observer Group. Only two senators traveled to observe New START negotiations. There was no spirit of cooperation or strong bipartisan support for the treaty. The Working Group essentially became a courtroom where New START could be prosecuted.

The Future of the NSWG

Since the vote on New START, the NSWG has not been any more successful in helping to foster bipartisanship. At the beginning of the 113th session of Congress, Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) and Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) were appointed co-chairs. Senator Rubio, like Senator Kyl, has attempted to impede the Obama Administration’s work on arms control.

While the cooperative atmosphere that surrounded the Arms Control Observer Group seems like an anachronism in today’s political climate, this is not meant to argue that senators within the Working Group need to agree on everything. There were major disagreements over nuclear policy during the Reagan administration and at times, heated discussions within the Observer Group. The difference was that the Observer Group was effective because the senators who were in it believed that arms control could advance U.S. national interests and wanted the group to succeed.

Today, the NSWG suffers from three broader trends within the United States that inhibit this attitude. The first is that the partisanship that exists in the Working Group is a reflection of the divisions in Congress. Given this dynamic, if there is any chance for the NSWG to serve as a valuable forum, individuals looking for the spotlight cannot be given the opportunity to hijack it. Secondly, since the end of the Cold War, detailed, negotiated arms control agreements are decreasingly seen as important to advancing U.S. national interests. There is diminishing prestige or interest in being a member of the NSWG or in supporting arms control. Thirdly, the Republican Party is far more skeptical about any legally binding international commitments than it once was.

These trends are unfortunate. The fact is that arms control still has a role to play in advancing U.S. interests and promoting international peace and stability. There are numerous issues that the United States and Russia will still need to address together. They continue to cooperate on issues related to Iran and reducing the risk of nuclear terrorism. They will likely still continue to communicate about issues related to U.S. missile defense deployment. Some think that current problems between the United States and Russia are evidence that this is not the case, but it was this kind of tension that led both countries to arms control in the first place. For this reason, diplomacy will remain an important policy tool for preventing catastrophic war between the two countries.

With diminishing nuclear policy expertise in a divided Senate, there is a need for a group of engaged, knowledgeable senators invested in arms control. For this reason, the NSWG will continue to have the opportunity to play a constructive role in informing the Senate on these issues and allowing senators into the diplomatic process.

The first members of the Group were Senator Ted Stevens (R-Alaska), Sam Nunn (D-Georgia), Richard Lugar (R-Indiana), Claiborne Pell (D-Rhode Island), Al Gore (D-Tennessee), Ted Kennedy (D-Massachusetts), Pat Moynihan (D-New York), Don Nickles (R-Oklahoma), John Warner (R-Virginia), and Malcolm Wallop (R-Wyoming).

Foreword, Report of the Senate Arms Control Observer Group Delegation to the Opening of the Arms Control, Negotiations with the Soviet Union in Geneva, Switzerland, March 9-12, (III) 1985.

Origin and Summary of Activities, Report of the Senate Arms Control Observer Group Delegation to the Opening of the ArmsControl, Negotiations with the Soviet Union in Geneva, Switzerland, March 9-12, 1985.

Transcript of Press Conference of Observer Group in Geneva, March 12, 1985, Report of the Senate Arms Control Observer Group Delegation to the Opening of the Arms Control, Negotiations with the Soviet Union in Geneva, Switzerland, March 9-12, 1985.

Origin and Summary of Activities, Report of the Senate Arms Control Observer Group Delegation to the Opening of the Arms Control, Negotiations with the Soviet Union in Geneva, Switzerland, March 9-12, 1985.

Janne E. Nolan, “Preparing for the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review,” Arms Control Today, November 2000, http://www.armscontrol.org/act/2000_11/nolan

Congressional Staffer (April 4, 2013), personal interview.

Kyl, Jon, Memo to National Security Working Group Republican Members: Report on the NSWG CODEL to Observe the Geneva Negotiations, November 23, 2009, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/images/091123_20091121_-_Kyl_Memo_to_NSWG_-_NSWG_START_mission.pdf.

Senator Carl Levin (MI), “Authorizing Expenditures by Committees,” Congressional Record (March 5, 2013), p. S1103.

Kristine Bergstrom, “Rubio vs Gottemoeller: The New Partisan Politics of Senate Nuclear Confirmations,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 7, 2014, http://carnegieendowment.org/2014/03/07/rose-gottemoeller-marco-rubio-and-new-partisan-politics-of-senate-nuclear-confirmations/h2mq.

Nickolas Roth is a research associate at the Project on Managing the Atom in the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard Kennedy School. Nickolas Roth previously worked as a policy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, where he wrote extensively about the industrial infrastructure responsible for maintaining the nuclear weapons stockpile. Mr. Roth has a B.A. in History from American University and a Masters of Public Policy from the University of Maryland, where he is currently a research fellow. Mr. Roth’s written work has appeared or been cited in dozens of media outlets around the world, including the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, USA Today, Asahi Shimbun, Boston Globe, and Newsweek.

American Scientists and Nuclear Weapons Policy

“Those who don’t know history are destined to repeat it,” warned British statesman and philosopher Edmund Burke more than 200 years ago. Having recently delved into reading about the history of the first group of American atomic scientists and their efforts to deal with the nuclear arms race, I have realized that Burke was right. More so, I would underscore that the ideas of these intellectual path-breakers are still very much alive today, and that even when we are fully cognizant of this history we are bound to repeat it. By studying these scientists’ ideas, Robert Gilpin in his 1962 book, American Scientists and Nuclear Weapons Policy, identifies three schools of thought: (1) control, (2) finite containment, and (3) infinite containment.

The control school had its origins in the Franck Report, which had James Franck, an atomic scientist at the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago serve as the lead drafter of the report which argued that “any international agreement on prevention of nuclear armaments must be backed by actual and efficient controls.” Seventy Manhattan Project scientists signed this report in June 1945, which was then sent to Secretary of War Henry Stimson. They suggested that instead of detonating atomic bombs on Japan, the United States might demonstrate the new weapon on “a barren island” and thus say to the world, “You see what sort of a weapon we had but did not use. We are ready to renounce its use in the future if other nations join us in this renunciation and agree to the establishment of an efficient control.” As we all know, the United States government did not take this advice during the Second World War.

But in 1946, the United States put forward in the Acheson-Lilienthal Report (in which J. Robert Oppenheimer, scientific director of the Manhattan Project, served as the lead drafter) ideas for international control of atomic energy. In the form of the Baruch Plan, this proposal before the fledging United Nations faced opposition from the Soviet Union, which wanted to arm itself with nuclear weapons before accepting a U.S. plan that could leave the United States wielding a monopoly on nuclear arms. However, the control school has been kept alive in part, through the founding in 1957 of the International Atomic Energy Agency, which has the dual mission to promote peaceful nuclear power and safeguard these programs. Periodically, concepts are still put forward to create multilateral means to exert some control over uranium enrichment and reprocessing of plutonium, the methods to make fissile material for nuclear reactors or bombs. Many of the founders and leading scientists of FAS such as Philip Morrison and Linus Pauling belonged to the control school.

Starting in the late 1940s, disillusionment about the feasibility of international control was setting in among several atomic scientists active in FAS and advisory roles for the government. They began to see the necessity for making nuclear weapons to contain the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, there were those who believed that international controls should continue to be pursued in parallel with production of atomic bombs. Thus, a sharp division did not exist between the control and finite containment schools of thought. Oppenheimer exemplified this view in a speech on September 17, 1947, to the National War College where he extolled the “soundness” of the control proposals but lamented that “the very bases for international control between the United States and the Soviet Union were being eradicated by a revelation of their deep conflicts of interest, the deep and apparently mutual repugnance of their ways of life, and the apparent conviction on the part of the Soviet Union of the inevitably of conflict—and not in ideas alone, but in force.”

Reading this, I think of the dilemma the United States faces with Iran over efforts to control the Iranian nuclear program while confronting decades of mistrust. One big difference between Iran and the Soviet Union is that Iran, as a non-nuclear weapon state party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, is legally obligated to not make or acquire nuclear explosives whereas the Soviet Union never had such legal restrictions. Thus, Iran has already agreed to accept controls through safeguards on its nuclear program. The question is what additional controls Iran will agree to accept in order to provide needed assurances that it does not have a nuclear weapons program and will not develop such in the future. In parallel, the United States is strengthening containment mostly via a military presence in the Persian Gulf region and providing weapons and defense systems to U.S. allies in the Middle East. Scientists play vital roles both in improving methods of control via monitoring, safeguarding, and verifying Iran’s nuclear activities and in designing new military weapon systems for containment through the threat of force.

How much military force is enough to contain or deter? The scientists who believed in finite containment were generally reluctant, and even some were opposed, to advocating for more and more powerful weapons. As Gilpin examines in his book, the first major schism among the scientists was during the internal government debate in 1949 and 1950 about whether to develop the hydrogen bomb. In particular, the finite containment scientists on the General Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission assessed that “an American decision not to construct the hydrogen bomb would again symbolize the sincerity of America’s desire to end the atomic arms race.”

In contrast, the infinite containment school that included Edward Teller (who was instrumental in designing the hydrogen bomb), and Ernest Lawrence (who was a scientific leader during the Manhattan Project and was based at the University of California, Berkeley), “argued that control over nuclear weapons would only be possible in a completely open world such as that envisioned in the Baruch Plan. Under the conditions of modern science, the arms race would therefore be unavoidable until the political differences underlying that arms race were settled” in the words of Gilpin. Many of the infinite containment scientists were the strongest advocates for declassifying nuclear secrets as long as there were firm assurances that nations had joined together to prevent the use of nuclear energy for military purposes or that “peace-loving nations had a sufficient arsenal of atomic weapons [to] destroy the will of aggressive nations to wage war.” In effect, they were arguing for world government or for a coalition of allied nations to enforce world peace.

Readers will be reminded of many instances in which history has repeated itself as mirrored by the control, finite containment, and infinite containment ways of thought arising from the atomic scientists’ movement of the 1940s and 1950s. Despite the disagreements among these “schools,” a common belief is that the scientists “knew that technical breakthroughs rarely come unless one is looking for them and that if the best minds of the country were brought in to concentrate on the problem, someone would find a solution … if there were one to be found,” according to Gilpin. Gilpin also astutely recommended that “wisdom flourishes best and error is avoided most effectively in an atmosphere of intellectual give and take where scientists of opposed political persuasions are pitted against one another.” Finally, he uncovered a most effective technique for “bring[ing] about the integration of the technical and policy aspects of policy” through “the contracted study project … wherein experts from both inside and outside of the government meet together over a period of months to fashion policy suggestions in a broad area of national concern.”

This, in effect, is the new operational model for much of FAS’s work. We are forming study groups and task forces that include diverse groups of technical and policy experts from both inside and outside the government. Stay tuned to reports from FAS as these groups tackle urgent and important science-based national security problems.

Charles D. Ferguson, Ph.D.

President, Federation of American Scientists