China’s Bulava?

|

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Similar to Russia’s troubled Bulava sea-launched ballistic missile, the Pentagon’s latest report on China’s military power reveals that Chinese efforts to develop a new sea-based nuclear missile have run into problems.

Other nuclear force developments described in the Pentagon’s delayed annual report on China’s military power, now renamed Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, include a slow deployment of new land-based mobile missiles and nuclear command and control challenges.

Naval Nuclear Programs

While the first boat of a small class of new Jin-class (Type 094) sea-launched ballistic missile submarines “appears ready” and up to four more may be building, development of the long-range ballistic missile Julang-2 for the class is said to have “encountered difficulty.”

The report reveals that the new missile has been “failing several of what should have been the final round of flight tests.”

| Julang-2 “Dry” Launch |

|

| The Pentagon says China’s new sea-launched ballistic missile has failed several tests. |

.

The latest setback continues the problems that have characterized China’s naval nuclear program over the years. The first SSBN program (Type 092) only produced one boat, the Xia, which has never sailed on a deterrent patrol. Even following a recent lengthy submarine overhaul, the Pentagon describes the operational status of the Xia’s Julang-1 missile system as “questionable.”

The nuclear-powered attack submarine program also seems challenged, with only two Shang-class (Type 093) boats operational – the same as last year – and four old Han-class (Type 091) boats still in service. Instead, the focus of the nuclear attack submarine program appears to have shifted to building a new class, the Type 095. The Pentagon report projects that “up to five” Type 095s may be added “in the coming years.”

Land-Based Nuclear Missiles

Introduction of new land-based mobile ballistic missiles continues, but at a slow pace. The DF-31 program appears stagnant at “<10” missiles, the same as reported last year. The number of intercontinental DF-31As has only increased by a couple of missiles, from “<10” last year to “10-15” in this year’s report.

| DF-31A Parading in Beijing |

|

| Deployment of the DF-31 and DF-31A has been slow, new Pentagon report shows. |

.

Probably as a possible result of the slow deployment of the new DF-31, the number of old liquid-fueled DF-3A and DF-4 missiles remain the same as last year.

Despite a strong display at the military parade in Beijing last year, the number of DF-21 launchers has not increased compared with last year. The number of missiles is a little higher, 85-90 missiles versus 60-80, probably reflecting addition of conventional DF-21C versions.

The report continues previous years’ predictions that a new road-mobile ICBM may be under development, possibly a reference to the elusive DF-41 or another system. The new missile is described as “possibly capable of carrying a multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicle (MIRV).”

Previous reports have reported development of MIRV technology for many years, but always concluded that MIRV technology for mobile missiles would be too difficult and expensive. The reference to a road-mobile ICBM MIRV capability is new, although it comes with a lot of caveats: “may be under development,” and “possibly capable of carrying” MIRV.

A MIRV system would, if deployed, represent a significant change in Chinese nuclear employment strategy. Russia and the United States deployed MIRVed systems to improve targeting against military targets. A secondary reason – for Britain it was probably the primary reason – was to overwhelm missile defenses.

Rather than increased targeting, the Chinese motivation for pursuing MIRV probably is the emergence of increasingly advanced U.S. ballistic missile systems. Phase 4 of the Obama administration’s Phased Adaptive Approach (PAA) includes an anti-ballistic missile defense capability against ICBMs from around 2020. This may push China further toward MIRV.

| Julang-1 Loading |

|

| Could loading of nuclear missiles in a crisis affect crisis stability? |

Nuclear Command and Control

As were the case with the 2009 report, the 2010 report underscores the command and control issues facing Chinese leaders. “The introduction of more mobile systems will create new command and control challenges for China’s leadership, which now confronts a different set of variables related to deployment and release authorities.”

One of these is the emerging SSBN force, an almost entirely new form of nuclear deployment in Chinese posturing. The report states that “the PLA has only a limited capacity to communicate with submarines at sea, and the PLA Navy has no experience in managing a SSBN fleet that performs strategic patrols with live nuclear warheads mated to missiles.”

Chinese SSBNs have never performed a strategic deterrent patrol (none were conducted in 2009), and if current Chinese doctrine is any indication it is doubtful that the SSBNs will deploy with “live nuclear warheads mated to missiles” in peacetime. But the absence of operational experience and the limited communication capability raises serious questions about how inadequate proficiency and launch control procedures might create problems in a crisis.

The report raises similar issues with the emergency of the new generation of land-based mobile missiles. Although China has operated medium-range mobile missiles for decades, the delegation of launch authority in a crisis to units with quicker-launch solid-fuel long-range missiles raises questions about use control, crisis stability, and misunderstandings.

| DF-31A on Launch Pad |

|

| How will quicker-firing long-range missiles such as the DF-31A affect command and control and delegation of launch authority? |

.

And there “is little evidence,” the Pentagon concludes, “that China’s military and civilian leaders have fully thought through the global and systemic effects that would be associated with the employment of these strategic capabilities.”

Despite these issues and speculations in previous annual Pentagon reports and the public about possible changes to Chinese nuclear doctrine, particularly conditions to its no-first-use policy, the 2010 report concludes that, “there has been no indication that national leaders are willing to attach such nuances and caveats to China’s ‘no first use’ doctrine.”

See also: previous blogs about China

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

India and Pakistan: Whose is Bigger?

|

| India-Pakistan nuclear competition on display again |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

If Indian news reports (here, here, and here) are any indication, India has once again discovered that Pakistan might possess a few nuclear weapons more than India.

This time the reports are based on an article Robert Norris and I published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, in which we provide estimates for the number of nuclear weapons in the world.

In 2009, our report on Pakistan’s nuclear forces triggered a statement from the chief of the Indian army that if the warhead estimate in our report was correct then Pakistan had moved beyond what is needed for deterrence. The unintended acknowledgement: so had India.

In 2008, reports about the arrival of the first Chinese Jin-class SSBN at a naval base on Hainan Island were followed by suggestions that India needed to build perhaps five new Arihant-class ballistic missile submarines.

As far as I can gauge, apart from nuclear testing where India started first, Pakistan has always been a little ahead in warheads, fissile material, and delivery systems. But neither country can claim any nuclear moral high ground; both are increasing their nuclear arsenals, both are producing more fissile material for nuclear weapons, and both are diversifying the means to deliver nuclear weapons and extending their range.

The two countries are now at a warhead level about equal to that of Israel (~80 warheads). But whereas it took Israel 40 years to reach that level, India and Pakistan have done so in only 12 years. And they’re apparently not done.

Although neither government wants to say so publicly, India and Pakistan are in effect in a nuclear arms race. It might not be of the intensity of the Cold War arms race between the Soviet Union and the United States, but it is a race nonetheless for capability and systems. Pointing to the other side having more only underscores that dynamic.

Indian and Pakistani security will probably be served better by trying soon to define just how big a nuclear force is sufficient for minimum deterrence so that “prudent planning” doesn’t take them to a new and more dangerous level.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Commanders Endorse New START

|

| The men behind a decade and a half of U.S. strategic nuclear planning say the New START treaty will enhance American national security. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Seven former commanders of U.S. nuclear strategic planning have endorsed the New START treaty and recommended early ratification by the U.S. Senate.

In a letter sent to Senator Carl Levin and John McCain of the Senate Armed Services Committee and Senators John Kerry and Richard Lugar of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the retired nuclear commanders conclude that the treaty “will enhance American national security in several important ways.”

The list includes four former commanders of U.S. Strategic Air Command (SAC) and four former commanders of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) – one served both as SAC and STRATCOM commander – who were responsible for U.S. strategic nuclear war planning and for executing the strategic war plan during the last phases of the Cold War and until as recently as 2004.

In doing so, the nuclear commanders – who certainly can’t be accused of being peaceniks – effectively pull the rug under the feet of the small number of conservative Senators who have held the treaty and U.S. nuclear policy hostage with a barrage of nitpicking and frivolous questions and claims about weakening U.S. national security interests.

The endorsement by the former nuclear commanders adds to the extensive list of current and former military and civilian leaders who have recommended ratification of the New START treaty. In fact, it is hard to find any credible leader who does not support ratification.

It’s time to end the show and do what’s right: ratify the New START treaty!

REPRODUCTION OF LETTER:

July 14, 2010

Senator Carl Levin, Chairman, Armed Services Committee

Senator John McCain, Ranking Member, Senate Armed Services CommitteeSenator John F. Kerry, Chairman, Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Senator Richard G. Lugar, Ranking Member, Senate Foreign Relations CommitteeGentlemen:

As former commanders of Strategic Air Command and U.S. Strategic Command, we collectively spent many years providing oversight, direction and maintenance of U.S. strategic nuclear forces and advising presidents from Ronald Reagan to George W. Bush on strategic nuclear policy. We are writing to express our support for ratification of the New START Treaty. The treaty will enhance American national security in several important ways.

First, while it was not possible at this time to address the important issues of non-strategic weapons and total strategic nuclear stockpiles, the New START Treaty sustains limits on deployed Russian strategic nuclear weapons that will allow the United States to continue to reduce its own deployed strategic nuclear weapons. Given the end of the Cold War, there is little concern today about the probability of a Russian nuclear attack. But continuing the formal strategic arms reduction process will contribute to a more productive and safer relationship with Russia.

Second, the New START Treaty contains verification and transparency measures—such as data exchanges, periodic data updates, notifications, unique identifiers on strategic systems, some access to telemetry and on-site inspections—that will give us important insights into Russian strategic nuclear forces and how they operate those forces. We will understand Russian strategic forces much better with the treaty than would be the case without it. For example, the treaty permits on-site inspections that will allow us to observe and confirm the number of warheads on individual Russian missiles; we cannot do that with just national technical means of verification. That kind of transparency will contribute to a more stable relationship between our two countries. It will also give us greater predictability about Russian strategic forces, so that we can make better-informed decisions about how we shape and operate our own forces.

Third, although the New START Treaty will require U.S. reductions, we believe that the post-treaty force will represent a survivable, robust and effective deterrent, one fully capable of deterring attack on both the United States and America’s allies and partners.

The Department of Defense has said that it will, under the treaty, maintain 14 Trident ballistic missile submarines, each equipped to carry 20 Trident D-5 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). As two of the 14 submarines are normally in long-term maintenance without missiles on board, the U.S. Navy will deploy 240 Trident SLBMs.

Under the treaty’s terms, the United States will also be able to deploy up to 420 Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and up to 60 heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments. That will continue to be a formidable force that will ensure deterrence and give the President, should it be necessary, a broad range of military options.

We understand that one major concern about the treaty is whether or not it will affect U.S. missile defense plans. The treaty preamble notes the interrelationship between offense and defense; this is a simple and long-accepted reality. The size of one side’s missile defenses can affect the strategic offensive forces of the other. But the treaty provides no meaningful constraint on U.S. missile defense plans. The prohibition on placing missile defense interceptors in ICBM or SLBM launchers does not constrain us from planned deployments.

The New START Treaty will contribute to a more stable U.S.-Russian relationship. We strongly endorse its early ratification and entry into force.

Sincerely,

General Bennie Davis (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1981-1985]

General Larry Welch (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1985-1986]

General John Chain (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1986-1991]

General Lee Butler (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1991-1992, STRATCOM CINC 1992-1994]

Admiral Henry Chiles (USN, Ret) [STRATCOM CINC 1994-1996]

General Eugene Habiger (USAF, Ret) [STRATCOM CINC 1996-1998]

Admiral James Ellis (USN, Ret) [STRATCOM CINC 2002-2004]

The original letter is here.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START and Missile Defense

I have not written here on the New START treaty, in part because everything that can be said has been said, well, almost everything…see below. The treaty is in no way revolutionary. I don’t think Reagan would bat an eyelash at it. Yet, while there is widespread bipartisan support for the treaty, including almost all the leading defense specialists from former Republican administrations, there is also some opposition to the treaty, with the Heritage Foundation having taken it on as a cause. Some of the critiques are truly bizarre, such as the treaty does not address Russian tactical nuclear weapons or North Korea. (On that last point, would one of the critics please sketch out how we would have included North Korea in the negotiation?) Of course, no past arms control treaty has ever covered every type of weapon and if New START is not ratified then any chance of negotiating limits on tactical nuclear weapons is off the table completely. (The treaty does not cure world hunger either, another good cause.)

The one issue that opponents consistently latch onto is the supposed limits on missile defense. There is language in the preamble drawing attention to the connection between offensive and defensive missiles and in the text there is a limit on converting offensive missile launchers to be able to launch defensive missiles. Administration spokesmen have addressed these criticisms by saying the preamble language is not binding. I find it very strange that advocates of missile defense would like to argue that there is no connection between offensive and defensive missiles. Of course there is a connection between the two of them. Isn’t one supposed to shoot down the other? Isn’t that a connection? It is like arguing there is no connection between ships and torpedoes. (I think the connection is actually quite weak because defensive missiles probably cannot shoot much down, but that is a different story.) Simply saying that doesn’t seem to change much. (more…)

Nuclear Plan Shows Cuts and Massive Investments

The Obama administration’s first nuclear weapons stockpile management plan is ready

By Hans M. Kristensen

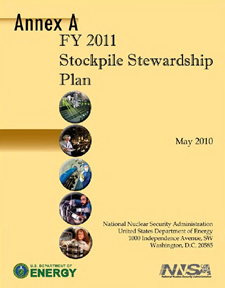

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has sent Congress the FY 2011 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) with new information about what the administration plans to spend on maintaining and modernizing nuclear weapons and facilities over the next 15-20 years.

FAS and UCS got hold of the unclassified sections of the plan and have analyzed what the Obama administration’s first nuclear weapons management plan tells us about how the Prague speech vision will be translated into national nuclear weapons policy. The SSMP consists of five sections (three are unclassified):

- FY 2011 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan Summary (unclassified)

- Annex A – FY 2011 Stockpile Stewardship Plan (unclassified)

- Annex B – FY 2011 Stockpile Management Plan (classified)

- Annex C – FY 2011 Science, Technology, and Engineering Report on Stockpile Stewardship Criteria and Assessment of Stockpile Stewardship Program (classified), and

- Annex D – FY 2011 Biennial Plan and Budget Assessment on the Modernization and Refurbishment of the Nuclear Security Complex (unclassified)

Smaller Nuclear Stockpile Planned

The good news is that plan shows that the United States intends to reduce the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile by 30 to 40 percent from today’s total of approximately 5,000 weapons to 3,000-3,500 weapons at least by 2022.

Initiatives already underway from the previous administration are currently reducing the arsenal to some 4,700 weapons by the end of 2012, and the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) released in April will likely result in additional reserve weapons being retired.

The “3,000 to 3,500 active, logistic spare, and reserve warheads” would be the largest stockpile that could be supported by the weapons industrial complex proposed by the new plan, and about twice the size of the New START treaty limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads (note that the stockpile also contains non-strategic and non-deployed warheads).

Massive Investments Forecast

The reduction comes at a considerable price. To support the stockpile, the NNSA intends to spend more than $175 billion (in then-year dollars) over the next two decades on building new nuclear weapons factories, testing and simulation facilities, and modernizing and extending the life of the nuclear weapons in the stockpile.

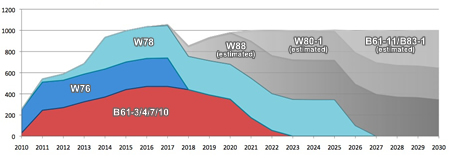

The plan shows for the first time how much will be spent on modernizing and extending the life of three nuclear weapons: the B61 gravity bomb, the W76 sea-based strategic warhead, and the W78 land-based strategic warhead. The cost is approximately $10 billion (in then-year dollars) between 2010 and 2025, peaking at about $1.05 billion in 2017 (at about the same time the New START strategic arms reduction treaty enters into force). Additional costs will follow as the remaining warheads in the stockpile are modernized and life-extended, projected at $1 billion per year in 2021-2030 (in then-year dollars).

.

The plan does not include the more than $100 billion the Department of Defense is expected to spend in 2010-2030 on the platforms needed to deliver the warheads. This includes a new class of ballistic missile submarines (estimated at $80 billion-plus), a new long-range bomber (presumably with a new cruise missile), and a new tactical fighter-bomber. (See latest Nuclear Notebook on US forces)

Smaller Stockpile, Expensive Complex

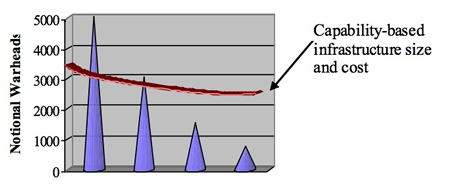

One of the more interesting parts of the plan is NNSA’s claim that even a much smaller nuclear weapons stockpile “would not lead to a smaller, less costly infrastructure” than the one proposed. In fact, NNSA concludes, “the costs to maintain capabilities necessary to support the stockpile are essentially independent of the size of the stockpile.” (Emphasis added)

| NNSA Stockpile-Complex Cost Matrix

|

|

| The NNSA plan suggests that the infrastructure needed to support a stockpile of less than 1,000 warheads will be about the same size and cost about as much money as the infrastructure needed to support a stockpile of 3,500 warheads.

|

.

According to NNSA’s calculations, even for a nuclear weapons stockpile of about 500 weapons, the size and cost of the infrastructure would be essential the same as what NNSA says is needed for a stockpile of 3,000-3,500 weapons. “After achieving a capability-based infrastructure, smaller total stockpiles than prescribed by post-NPR implementation strategies would not lead to a smaller, less costly infrastructure.” The basis for the argument is that even with 500 weapons, maintaining them would, in NNSA’s assessment, involve the same basic work and facilities as with the larger stockpile.

It is not uncommon to hear claims that proposed funding is the absolute minimum possible, but this claim will demand a lot of scrutiny in the months and years ahead. It implies that today’s complex maintaining 5,000 weapons would be about the same size and cost as the complex needed to maintain 8,000 weapons, which of course is not the case.

“New” Weapons or Just New Weapons

| New Capabilities Planned

|

|

| The NNSA plan includes new capabilities, such as Arming, Fuzing & Firing (AF&AF) for all the warheads in the stockpile

|

The plan echoes the NPR’s promise that the United States will not build “new” nuclear weapons, but it shows that there are plenty of modernization options short of “new.”

Until a few years ago, the United States did not have the capacity to build new nuclear weapons. Since then, however, production of new W88 warheads has restarted and “war reserve” W88s are now entering the stockpile to replace those destroyed in surveillance tests. Other warhead types will follow in the years to come. The SSMP includes plans for building new nuclear weapons production facilities to ramp up warhead production capacity from 20 per year today to 80 per year by 2022.

The planned W78 modernization is described as “the next reentry system,” and the NNSA plan states that modernizing the complex will ensure that “the development cycle of future weapons is compressed.”

The plan strongly commits to continuing “current weapon alterations and modifications” and for adding “alterations/modifications to the enduring stockpile (or future strategic systems).” This includes advanced designs to “enable vastly improved capabilities for next system arming, fuzing, and firing [AF&F] and/or radar componentry….”

AF&F and radar systems are not part of the nuclear explosive package and therefore not normally considered covered by the pledge not to improve military capabilities of nuclear warheads. But “vastly improved capabilities” for AF&F and radar systems can significantly improve the military capabilities of a weapon and change the scenarios in which it can be used. One example is the new AF&F installed on the W76-1 during the current life-extension program, which adds new height of burst settings that increase the type of facilities the weapon can be used against. Another example is the B61-11 introduced in 1997, which is a modified B61-7 but with significantly different military capabilities.

Safety and Security as Modernization Drivers

Another category of warhead modernizations described in the plan involves the addition of new safety and security features to existing (and future) warheads. The demand for increased surety, as safety and security are jointly called, was triggered by the terrorist attacks in 2001 and has resulted in the pursuit of what the NNSA plan describes as “effective, affordable use denial options that address 21st century threats.”

| Safety and Security Pursuit

|

|

| Additional nuclear surety capabilities have become important divers for warhead modernization: all warheads will get some

|

It is not clear why the requirement for new surety features has increased, much less how much is needed. The same weapons were deployed before 2001 without any problems, but NNSA states that the new surety features are being pursued “independent of any threat scenario.”

In the near-term, the development focuses on new power management systems, security sensors, and integrated surety solutions such as advanced internal/external use-denial technologies. Warheads refurbished after 2010 will get new stronglink concepts, optical firing sets, and detonator safing. Longer-term developments include “multi-point safety for future insertion opportunities,” a capability that can significantly affect the nuclear package.

Most people obviously see nuclear weapons safety and security as important, but the addition of new features will gradually bring modified life-extended warheads further from their tested design. Since this could lead to demands for warhead replacements or even testing in the future, and given “the high cost and long time frame associated with integrating, qualifying, and certifying deeply buried subsystems through the LEP process,” a cost-benefit assessment is needed to create a benchmark for how much surety is enough.

And it is important to remember that nuclear weapons surety is not only a matter of what adversaries might do. Does our deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe and atop missiles on alert expose the weapons to additional risks that could be mitigated much cheaper and effectively by withdrawing and de-alerting the weapons?

Plan in Prague Speech Context

The nuclear investments forecast by the NNSA plan – combined with DOD modernization plans – should help undercut claims by (ultra)conservatives and uninformed that the New START treaty with Russia will somehow put the United States at a disadvantage.

Yet the massive investments to build weapons factories and modify warheads also raise questions about how the plan will be seen by the international community that is needed to support the Obama administration’s nonproliferation agenda. How will other nuclear weapon states interpret the plan and U.S. intensions, given that they need to be convinced to reduce, stop producing, and ultimately eliminate nuclear weapons to make nuclear reductions and eventually disarmament a reality?

In his Prague speech in April 2009, President Obama made a dual pledge: On the one hand, to “take concrete steps towards a world without nuclear weapons,” and to “put an end to Cold War thinking” by reducing “the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same.” On the other hand, he pledged to “maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies….” Whereas the president spoke of maintaining a nuclear deterrent, the NNSA plan speaks of “evolving and sustaining the nuclear deterrent.” (Emphasis added)

Likewise, while Congress during the past decade canceled or delayed, as NNSA describes them, “opportunities to exercise the full suite of design competencies through life extensions and modernizations” of nuclear weapons (presumably the Nuclear Robust Earth Penetrator and the Reliable Replacement Warhead), the new plan is designed for “providing the opportunity to fully exercise design and production skills” and “vastly improved capabilities” of modified warhead components.

The plan does echo the pledge to reduce the nuclear weapons stockpile, but that goal is conditioned on building new nuclear weapons production factories and creating a “more agile deterrent.” As the plan bluntly states, a “multi-year and steady investment in the modernization of the complex is an essential element of the NPR, allowing the United States to safely reduce the role of nuclear weapons.”

Striking a balance between disarmament and deterrence – a balance that conveys an clear transition towards disarmament – will be delicate and the administration must work to ensure that the goodwill of Prague is not undercut by nuclear modernizations.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

FAS Contributes to SIPRI Yearbook

|

By Hans M. Kristensen

The world’s nuclear weapon states possess an estimated 22,600 nuclear weapons, of which more than 7,500 are deployed. This and much more according to a chapter I co-authored in the latest yearbook from the Swedish International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

Copyright prevents us from making a copy of the chapter available here, but we’re allowed to share a PDF-copy with individual contacts. Otherwise a brief summary is available here. The estimates are similar to the ones I update on the FAS web site, with slight differences due to production time and counting categories, and are based on the analysis I do with Robert Norris in the Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NPT RevCon ends with a consensus Final Document

by Alicia Godsberg

The NPT Review Conference ended last Friday with the adoption by consensus of a Final Document that includes both a review of commitments and a forward looking action plan for nuclear disarmament, non-proliferation and the promotion of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. In the early part of last week it was unclear if consensus would be reached, as states entered last-minute negotiations over contentious issues. While the consensus document represents a real achievement and is a relief after the failure of the last Review Conference in 2005 to produce a similar document, much of the language in the action plan has been watered down from previous versions and documents, leaving the world to wait until the next review in 2015 to see how far these initial steps will take the global community toward fulfilling the Treaty’s goals. (more…)

Britain Discloses Size of Nuclear Stockpile: Who’s Next?

|

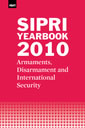

| Britain says it has 225 nuclear warheads for its Trident submarine fleet. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new British government today followed the French and U.S. examples by disclosing its total military stockpile of nuclear weapons.

Foreign Secretary William Hague told the House of Commons that “the total number of warheads” in the “overall stockpile” will not exceed 225. Of those, “up to 160” are “operationally available” for deployment on Trident II missiles on British ballistic missile submarines.

The Royal Navy possesses four Vanguard-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), each of which can carry up to 16 U.S.-supplied Trident II long-range ballistic missiles. Each missile is thought to carry up to three UK-produced warheads closely resembling the U.S. 100-kt W76 warhead.

Stockpile and Arsenal

Whereas the United States declassified its entire stockpile history, the British government has only disclosed the current size of its stockpile, and only in the somewhat cryptic way: “the overall stockpile…will not exceed 225 warheads.”

That presumably means the stockpile actually contains 225 warheads, not that it might be smaller but “not exceed 225 warheads” even in the future.

That is 25 warheads more than the 200 Robert Norris and I have estimated in the past.

Of the 225 warheads, the government stated that it “will retain up to 160 operationally available warheads,” or as many as 71 percent of the entire inventory. There are only spaces for 144 warheads on Britain’s 50 Trident II SLBMs, of which 48 can be deployed on three operational SSBNs. The fourth boat is in refit at any given time and is not allocated missiles.

| British Nuclear Weapons Stockpile 2010 |

|

| With the British government’s declaration, it’s possible to make an estimated breakdown of the categories of nuclear warheads in the British stockpile. |

.

The “up to 160” probably refers to the 144 spaces plus a small number of spare warheads. The number of spares might increase if an SSBN deploys with less than its maximum capacity of 48 warheads. The remaining 65 warheads in the stockpile are for what is described as “routine processing, maintenance and logistic management.”

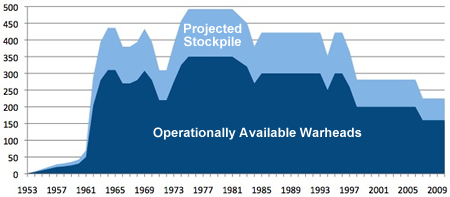

It is not yet possible to plot the history of the British nuclear stockpile with certainty. But if one assumes that the ratio of warheads in the non-operational reserve to the operationally available inventory has been roughly the same as today (approximately 1 x 2.5), then a simplistic projection of the stockpile looks like this:

| British Nuclear Weapons Stockpile 1953-2010 |

|

| The history of the British stockpile is unknown, but assuming the same percentage of warheads in reserve as today, a preliminary history can be plotted. |

.

The stockpile fluctuated considerably over the years with introduction and retirement of various weapon systems. The stockpile reached a peak in the late 1970s at nearly 500 warheads. After the Cold War, the stockpile decreased with the retirement of the WE-177 non-strategic nuclear bombs and depth charges for use by the air force and surface fleet. The last of the WE-177s was dismantled in August 1998.

Who’s Next?

Three of the five original nuclear weapon states have now disclosed the sizes of their military stockpiles of nuclear warheads. The pressure is increasing on the other nuclear weapon states to follow the good example.

The size of the Russian stockpile is unknown but Norris and I estimate Russia possesses 12,000 nuclear warheads, of which 4,600 might be operational. A Russian official recently told Reuters that Russia after ratification of the New START agreement “will likewise be able to consider disclosing the total number of Russia’s deployed strategic delivery vehicles and the warheads they can carry.” That would not be disclosing the size of the stockpile, but still be progress.

China’s stockpile is even more opaque, although Norris and I estimate it at approximately 240 warheads. That fits well with the declaration made by former British Defense Minister Des Browne in 2007, that the United Kingdom has “the smallest stockpile of any of the nuclear weapon states recognised under the NPT.”

Declarations from Indian and Pakistani would also be greatly welcomed. Israel is obviously a little more complicated because, well, it has yet to acknowledge that it has nuclear weapons, and North Korea doesn’t seem in the mood for goodwill gestures these days.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Speaking at the CSIS Global Security Forum

|

By Hans M. Kristensen

Clark Murdock and John Warden with the Center for Strategic and International Studies invited me to speak today at their Global Security Forum. My co-panelists were General Larry Welch (USAF, ret.) and Morton Halperin.

The question posed to us was whether the United States should, in a proliferated world, continue to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in its national security strategy. There were different views on how much and for what reasons the role could be reduced, but at least no one could envision a need to increase the role.

CSIS will probably make the video available online soon, but in the meantime here are my prepared remarks: (more…)

FAS side events at the RevCon

by Alicia Godsberg

Yesterday FAS premiered our documentary Paths To Zero at the NPT RevCon. The screening was a great success and there was a very engaging conversation afterward between the audience and Ivan Oelrich, who was there to promote the film. As a result of some suggestions, we are hoping to translate the narration to different languages so the film can be used as an educational tool around the world. You can see Paths To Zero by following this link – we will also be putting up the individual chapters soon.

This morning I spoke at a side event at the NPT RevCon entitled “Law Versus Doctrine: Assessing US and Russian Nuclear Postures.” I was asked to give FAS’s perspective on the New START, NPR, and new Russian military doctrine. Several people asked me for my remarks, so I’m posting them below the jump. (more…)

Russian Nuclear Weapons Account Falls Short

|

| A Russian brochure misrepresents the size of the Russian arsenal. Click image to download copy of full procure |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A brochure handed out by the Russian government at the ongoing nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference in New York appears to misrepresent the size of the Russian nuclear arsenal.

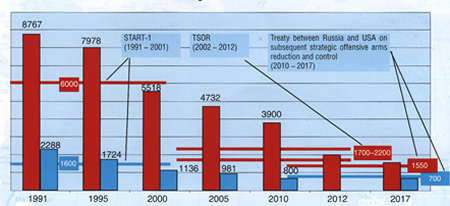

The brochure Practical steps of the Russian Federation in the field of nuclear disarmament includes a chart that lists the reduction in Russian strategic nuclear weapons under three arms control agreements and is intended to demonstrate Russia compliance with the NPT’s Article VI. The chart shows strategic warhead numbers for roughly five-year intervals in 1991-2017 and characterizes the numbers as the “actual quantity of nuclear weapons.”

But the numbers are not “actual quantities” of weapons but so-called aggregate numbers previously published in the Memorandum of Understanding exchanged by Moscow and Washington under the now expired START treaty.

| SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) |

|

| The brochure lists more strategic warheads in 2012 than Russian missiles can carry. |

The aggregate numbers are inaccurate because they include so-called phantom weapons that were not operational at the time, and because they attribute a declared warhead number to each delivery platform rather than what is actually deployed. The aggregate numbers also do not include strategic warheads that are not counted as deployed.

The number for 2012 on the graph is curious because it lists 2,000 strategic warheads, the medium value of the 1,700-2,200 of the Moscow Treaty. But since Russia doesn’t count its strategic bomber weapons as deployed under the Moscow Treaty and the New START agreement only counts one warhead per bomber, practically all of the listed 2,000 warheads would have to be on ballistic missiles. Yet the ballistic missiles Russia is projected to deploy in two years don’t have enough warhead spaces for 2,000 warheads.

The Russian brochure also illustrates the reduction that has occurred in Russian tactical nuclear weapons, stating that the current inventory is 25% of what it was in 1991. But, again, Russia fails to disclose the real number, which is now at an estimated 5,000 warheads.

| Russian Non-Strategic Weapons Reduced |

|

| The Russian brochure states that non-strategic warheads have been reduced but to what? |

.

The United States disclosed the size of its military nuclear weapons stockpile last week and has been declaring since 2006 how many of those warheads are deployed on ballistic missiles and heavy bomber bases. Russia should follow the American example and disclose the size of its nuclear weapons stockpile. Doing so would support Russian interests far better than outdated Cold War nuclear secrecy.

Ironically, Russia could have demonstrated deeper reductions had it listed its actual number of deployed strategic warheads instead of the aggregate numbers. Russia currently deploys an estimated 2,600 strategic warheads, significantly less than the 3,900 listed in the brochure. Transparency is better.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Speaking at the NPT-Review Conference

|

| The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference is Underway in New York |

By Hans M. Kristensen

I gave two talks at the review conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, both on non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The first was an FAS/BASIC panel on May 10 on Prospects for a shift in NATO’s nuclear posture.

The second was a panel organized by Pax Christi on May 12 on NATO’s nuclear policy.

My prepared remarks follow below:

U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Which Way Forward?

Hans M. Kristensen

Director, Nuclear Information Project

Federation of American Scientists

Presentation to FAS/BASIC Panel on Shifting NATO’s Nuclear Posture

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, New York, May 10, 2010I’ve been asked to talk about the status of the deployment in Europe and about the Obama administration’s policy. There are of course many other issues affecting the status and future of the deployment, but let me focus on those two here.

There are currently about 200 U.S. nuclear bombs deployed in Europe. That is a far cry from the peak of 7,300 tactical nuclear weapons that were deployed there in 1971. But comparing with the Cold War is no longer relevant; the issue is how the posture fits the security challenges of today.

The deployment currently is about as big as the entire Chinese arsenal, or nearly as much as India, Pakistan, and Israel have combined. That’s a lot for an arsenal that NATO says is not targeted or directed against anyone.

Yet for an alliance that officially emphasizes the importance of continued and widespread deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the past two decades have been a contradiction: since 1993 when the withdrawal of ground-launched and naval weapons was completed, these “essential” bombs have been reduced from 700 to 200, the number of nuclear bases reduced from 14 to 6, and the number of countries participating in the NATO strike mission reduced from six to four.

The burden sharing principle has been reduced to a shadow of it former self: out of NATO’s 28 members, only five (18 percent) have nuclear weapons on their territory, and only four (14 percent) have the strike mission. Most recently, three of the remaining four asked NATO to formally discuss the future of the mission.

The practice of equipping and training non-nuclear NPT signatories in NATO with U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities was largely tolerated by the NPT community during the Cold War. But this arrangement is untenable in an era where the focus is on nonproliferation because it muddles the message, condones double standards, and is – plain and simple – in contradiction with the intention of the NPT. It is not a standard NATO or the United States should defend today.

So although some officials cling to Cold War arguments for maintaining U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the reality is that it is entirely in line with post-Cold War NATO policy and actions to reduce, curtail, and phase out the nuclear mission. It’s not going the other way. So NATO’s focus should not be whether to withdraw the weapons but how.

The top of the new American administration supports a withdrawal from Europe. You might be surprised to hear that given Hillary Clinton’s statements in Tallinn last month and what some defense officials are saying inside. But those statements are part of a strategy intended to avoid triggering a backlash from some Eastern European NATO countries and Turkey that could lock NATO’s Strategic Concept into decades of nuclear status quo.

The strategy reflects that a clear priority of the Obama administration is to reassure allies and partners and repair the rift that began to open during the previous administration. The Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), the Ballistic Missile Defense Review (BMDR), and the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) all emphasize this, and all hint of changes to come in the European deployment.

The QDR states: “To reinforce U.S. commitments to our allies and partners, we will consult closely with them on new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent. These regional architectures and new capabilities, as detailed in the Ballistic Missile Defense Review and the forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review, make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” (Emphasis added.)

The BMDR is a little more explicit, stating: “Against nuclear-armed states, regional deterrence will necessarily include a nuclear component (whether forward-deployed or not). But the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in these regional deterrence architectures can be reduced by increasing the role of missile defenses and other capabilities.” (Emphasis added.)

Although the NPR states that the presence of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe and the nuclear sharing arrangement “contribute to Alliance cohesion and provide reassurance to allies and partners who feel exposed to regional threats,” it also reminds that extended deterrence relies less and less of nuclear weapons and that the role will continue to decrease as the new, regional, deterrence architecture matures.

This new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture includes all components of U.S. military capabilities, ranging from effective missile defense, counter-WMD capabilities, conventional power-projection capabilities, and integrated command and control – all underwritten by strong political commitments. The missile defense, the NPR states explicitly, is “part of our extended deterrent and a visible demonstration of our Article 5 commitment to Europe.”

So it is important to understand that the Obama administration sees its security commitments as much more – and increasingly other – than forward deployment of nuclear bombs in Europe. In fact, the forward deployment is the least relevant today, and many U.S. officials privately make no attempt to conceal that they would like to withdraw the weapons and for NATO to move out of the Cold War.

Not only does the NPR retire the nuclear Tomahawk that supported NATO, there are subtle hints that the nuclear bombs may be withdrawn. The NPR reminds that even if the bombs were withdrawn from Europe, the United States will “retain the capability to forward-deploy U.S. nuclear weapons on tactical fighter-bombers (in the future, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter) and heavy bombers (the B-2 and B-52H).” In addition, the NPR promises, the United States will “continue to maintain and develop long-range strike capabilities that supplement U.S. forward military presence and strengthen regional deterrence.”

The subtle point, I think, is that forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe is not very suitable for today’s security challenges, that regional deterrence and reassurance of allies are better served by a new regional security architecture that relies less on nuclear weapons, and that there are plenty of other nuclear capabilities to provide the nuclear umbrella anyway. But none of those changes to U.S. extended deterrence capabilities will be made, the NPR promises, without close consultations with allies and partners.

So I don’t think it’s matter of if but when and how the remaining U.S. weapons will be withdrawn from Europe. The problem with additional gradual unilateral reductions is that it’s hard to cut much more without looking increasingly silly when arguing that the few that will remain are still essential for NATO.

Well aware of this dilemma, opponents of withdrawal have proposed linking further cuts to reductions in Russian tactical nuclear weapons; they know full well that such a link would means nothing will happen anytime soon.

But making further reductions conditioned on Russia reducing its non-strategic nuclear weapons seems insincere because NATO for the past two decades has been perfectly capable of and willing to reduce unilaterally without any demands on Russia. Insisting on reciprocity now, when NATO has been insisting for years that the weapons are not directed against Russia, seems like a step back to the 1980s and intended to shield the last weapons against withdrawal.

Another reason why it makes little sense to link further reductions to Russian reductions is that the improved conventional and missile defense capabilities that are required by the new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture likely will deepen Russian concerns about NATO conventional capabilities. Even though Russia’s non-strategic forces are expected to decline significantly during the next decade, this will probably increase the importance of the remaining weapons in Russian thinking even more.

Fortunately, none of this prevents a unilateral withdrawal of the remaining U.S. weapons from Europe. Indeed, it seems that the way forward is perhaps a two-step process beginning with ending the nuclear sharing mission followed by complete withdrawal a little later. Whatever the schedule is, the good news is that reducing the deployment in Europe is both consistent with NATO history and security interests.

Thank you.

U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Status and Issues

Hans M. Kristensen

Presentation toPax Christi Panel on Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, New York, May 12, 2010I’ve been asked to talk about the status of the deployment in Europe and what some of the implications are for NATO.

The 200 U.S. nuclear bombs currently deployed in Europe are a far cry from the peak of 7,300 tactical nuclear weapons in 1971, but comparing with the Cold War is no longer relevant; the issue is how the posture fits the security challenges of today. The current deployment is about as big as the entire Chinese arsenal, or nearly as much as India, Pakistan, and Israel have combined. That’s a lot for an arsenal that NATO says has no military mission.

Yet for an alliance that officially emphasizes the importance of continued and widespread deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the past two decades have been somewhat of a contradiction: since 1993 when the withdrawal of ground-launched and naval weapons was completed, these “essential” bombs have been reduced from 700 to 200, the number of nuclear bases reduced from 14 to 6, and the number of countries participating in the NATO strike mission reduced from six to four countries that now appear to have serious doubts about continuing the mission. And burden sharing in NATO is actually not very widespread: out of NATO’s 28 members, only five (18 percent) have nuclear weapons on their territory, and only four of those (14 percent) have the strike mission. So nuclear burden sharing is the exception, not the rule, in NATO.

There are several issues that need to be addressed. The first is the mission. NATO is fond of saying that the forward deployment no longer has any military mission. It only serves as a symbol of the U.S. commitment to defend NATO, and without this forward symbol, so the argument goes, the U.S. security interest in Europe would weaken. Whether one agrees with this argument – and I for one believe it is absolutely nonsense – the last thing Europe should look to as the Atlantic glue is a deployment that the United States itself no longer thinks is important. There is a view forming back in Washington that it’s kind of silly for some of the NATO governments to continue to put so much emphasis on this deployment and you only have to look to the NPR report to see how much effort it makes to signal to Europe that extended deterrence and Article V do not depend on deploying nuclear bombs in Europe.

NATO is currently reviewing the nuclear mission, of which the forward deployment is a sub-issue. I think the deployment constrains the review and limits NATO’s ability think anew about the appropriate contribution of nuclear weapons to NATO security. No matter how the forward deployment has been adjusted and what one might otherwise think about the virtues of the deployment, it is at its core a Cold War posture.

Related to the mission review is the question of resources. The forward deployment requires special personnel, special equipment, special command and control, special inspections, special security arrangements, special emergency plans, special political and legal agreements, and special funding, all of which compete with conventional missions and place unnecessary burdens on people, equipment, and institutions. The weapons were withdrawn from Lakenheath and Ramstein partly because those bases needed to focus their mission on real-world contingencies. Those who insist that the deployment is still necessary need to demonstrate what the net benefit is to NATO.

The mission review is closely related to how the deployment affects relations with Russia and other potential adversaries. NATO has insisted for two decades that the weapons in Europe are not aimed at Russia or any country. That may or may not be true, but the deployment is frequently used by Russian officials as an excuse to reject constraints on their own non-strategic nuclear weapons. And Russian military planners will necessarily have to plan contingencies against potential NATO attacks with the weapons deployed in Europe. This ties NATO and Russia to a deterrence relationship that they don’t need to have, and that works against closer relations.

We now see some proposing that further reductions in the U.S. deployment should be linked to reductions in Russian non-strategic weapons. That would of course be one way to make sure the U.S. weapons are not withdrawn anytime soon, but making further reductions conditioned on Russia reducing its non-strategic nuclear weapons is misguided for several reasons. First, because NATO for the past two decades has been perfectly capable of and willing to reduce unilaterally without any demands on Russia. Second, the United States has unilaterally reduced its nonstrategic arsenal far more than Russia because these weapons are no longer seen as important to national security. Insisting on reciprocity now, when NATO has been insisting for years that the deployment is not linked to Russia, seems a step back that would give the European deployment an importance it doesn’t deserve and risk complicating prospects for Russian reductions.

Then there is the issue of safety. This is more significant than people generally think. The 200 weapons are scattered in 87 aircraft shelters at six bases in five countries. Ten years ago, the U.S. Air Force discovered that weapons maintenance procedures at the shelters under specific conditions could lead to accidents with a nuclear yield. Two years ago, the Air Force Blue Ribbon Review determined that security at the host country bases did not meet U.S. security standards. And just a few months ago, peace activists at Kleine Brogel demonstrated loudly and clearly that despite extensive security arrangements unauthorized people can get deep into a nuclear base and very close to the weapons. The widespread deployment was designed to survive a Soviet attack, but in today’s world widespread deployment is out of sync with nuclear weapons storage in the age of extreme terrorism.

Finally there is the issue of NATO’s nonproliferation standard. The practice of equipping and training non-nuclear NPT signatories in NATO with U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities was largely tolerated by the NPT community during the Cold War. But this arrangement is untenable in an era where the focus is on nonproliferation because it muddles the message, creates double standards, and is – plain and simple – in contradiction with the intention of the NPT. It is not a standard that NATO or the United States should defend today. The nuclear sharing is simply not important enough to justify this contradiction.

—

The top of the new American administration supports a withdrawal from Europe. You might be surprised to hear that given Hillary Clinton’s statements in Tallinn last month and what some defense officials are saying inside. But those statements are, I think, part of a strategy intended to avoid triggering a backlash from some Eastern European NATO countries and Turkey that could lock NATO’s Strategic Concept into another two decades of nuclear status quo.

Not only does the NPR retire the nuclear Tomahawk that supported NATO, there are subtle hints that the bombs may be withdrawn. The NPR reminds that even if the nuclear bombs were withdrawn from Europe, the United States will “retain the capability to forward-deploy U.S. nuclear weapons on tactical fighter-bombers (in the future, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter) and heavy bombers (the B-2 and B-52H).” In addition, the NPR promises, the United States will “continue to maintain and develop long-range strike capabilities that supplement U.S. forward military presence and strengthen regional deterrence.”

The subtle message to NATO, I think, is that the Obama administration does not believe that forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe is necessary for today’s security challenges, that regional deterrence and reassurance of allies are better served by a new regional security architecture that relies less on nuclear weapons, and that there are plenty of other nuclear capabilities to provide the nuclear umbrella to the limited extent that that is necessary. Such a posture has been in effect in Northeast Asia since 1992, and many U.S. officials privately make no attempt to conceal that they would like to withdraw the weapons from Europe too and for NATO to move on.

So I don’t think it’s matter of if but when and in what form the U.S. weapons will be withdrawn from Europe. A way forward might be a two-step process beginning with ending the nuclear sharing mission followed by complete withdrawal a little later. Whatever the schedule is, the good news is that reducing the deployment in Europe is both consistent with NATO history and security interests and the views of the new American administration.

Thank you.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.