Mobilizing Innovative Financial Mechanisms for Extreme Heat Adaptation Solutions in Developing Nations

Global heat deaths are projected to increase by 370% if direct action is not taken to limit the effects of climate change. The dire implications of rising global temperatures extend across a spectrum of risks, from health crises exacerbated by heat stress, malnutrition, and disease, to economic disparities that disproportionately affect vulnerable communities in the U.S. and in low- and middle-income countries. In light of these challenges, it is imperative to prioritize a coordinated effort at both national and international levels to enhance resilience to extreme heat. This effort must focus on developing and implementing comprehensive strategies to ensure the vulnerable developing countries facing the worst and disproportionate effects of climate change have the proper capacity for adaptation, as wealthier, developed nations mitigate their contributions to climate change.

To address these challenges, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) should mobilize finance through environmental impact bonds focused on scaling extreme heat adaptation solutions. USAID should build upon the success of the SERVIR joint initiative and expand it to include a partnership with NIHHIS to co-develop decision support tools for extreme heat. Additionally, the Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) within the USAID should take the lead in tracking and reporting on climate adaptation funding data. This effort will enhance transparency and ensure that adaptation and mitigation efforts are effectively prioritized. By addressing the urgent need for comprehensive adaptation strategies, we can mitigate the impacts of climate change, increase resilience through adaptation, and protect the most vulnerable communities from the increasing threats posed by extreme heat.

Challenge

Over the past 13 months, temperatures have hit record highs, with much of the world having just experienced their warmest June on record. Berkeley Earth predicts a 95% chance that 2024 will rank as the warmest year in history. Extreme heat drives interconnected impacts across multiple risk areas including: public health; food insecurity; health care system costs; climate migration and the growing transmission of life-threatening diseases.

Thus, as global temperatures continue to rise, resilience to extreme heat becomes a crucial element of climate change adaptation, necessitating a strategic federal response on both domestic and international scales.

Inequitable Economic and Health Impacts

Despite contributing least to global greenhouse gas emissions, low- and middle-income countries experience four times higher economic losses from excess heat relative to wealthier counterparts. The countries likely to suffer the most are those with the most humidity, i.e. tropical nations in the Global South. Two-thirds of global exposure to extreme heat occurs in urban areas in the Global South, where there are fewer resources to mitigate and adapt.

The health impacts associated with increased global extreme heat events are severe, with projections of up to 250,000 additional deaths annually between 2030 and 2050 due to heat stress, alongside malnutrition, malaria, and diarrheal diseases. The direct cost to the health sector could reach $4 billion per year, with 80% of the cost being shouldered by Sub-Saharan Africa. On the whole, low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) in the Global South experience a higher portion of adverse health effects from increasing climate variability despite their minimal contributions to global greenhouse emissions, underscoring a clear global inequity challenge.

This imbalance points to a crucial need for a focus on extreme heat in climate change adaptation efforts and the overall importance of international solidarity in bolstering adaptation capabilities in developing nations. It is more cost-effective to prepare localities for extreme heat now than to deal with the impacts later. However, most communities do not have comprehensive heat resilience strategies or effective early warning systems due to the lack of resources and the necessary data for risk assessment and management — reflected by the fact that only around 16% of global climate financing needs are being met, with far less still flowing to the Global South. Recent analysis from Climate Policy Initiative, an international climate policy research organization, shows that the global adaptation funding gap is widening, as developing countries are projected to require $212 billion per year for climate adaptation through 2030. The needs will only increase without direct policy action.

Opportunity: The Role of USAID in Climate Adaptation and Resilience

As the primary federal agency responsible for helping partner countries adapt to and build resilience against climate change, USAID announced multiple commitments at COP28 to advance climate adaptation efforts in developing nations. In December 2023, following COP28, Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and USAID Administrator Power announced that 31 companies and partners have responded to the President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience (PREPARE) Call to Action and committed $2.3 billion in additional adaptation finance. Per the State Department’s December 2023 Progress Report on President Biden’s Climate Finance Pledge, this funding level puts agencies on track to reach President Biden’s pledge of working with Congress to raise adaptation finance to $3 billion per year by 2024 as part of PREPARE.

USAID’s Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) leads the implementation of PREPARE. USAID’s entire adaptation portfolio was designed to contribute to PREPARE and align with the Action Plan released in September 2022 by the Biden Administration. USAID has further committed to better integrating adaptation in its Climate Strategy for 2022 to 2030 and established a target to support 500 million people’s adaptation efforts.

This strategy is complemented by USAID’s efforts to spearhead international action on extreme heat at the federal level, with the launch of its Global Sprint of Action on Extreme Heat in March 2024. This program started with the inaugural Global Heat Summit and ran through June 2024, calling on national and local governments, organizations, companies, universities, and youth leaders to take action to help prepare the world for extreme heat, alongside USAID Missions, IFRC and its 191-member National Societies. The executive branch was also advised to utilize the Guidance on Extreme Heat for Federal Agencies Operating Overseas and United States Government Implementing Partners.

On the whole, the USAID approach to climate change adaptation is aimed at predicting, preparing for, and mitigating the impacts of climate change in partner countries. The two main components of USAID’s approach to adaptation include climate risk management and climate information services. Climate risk management involves a “light-touch, staff-led process” for assessing, addressing, and adaptively managing climate risks in non-emergency development funding. The climate information services translate data, statistical analyses, and quantitative outputs into information and knowledge to support decision-making processes. Some climate information services include early warning systems, which are designed to enable governments’ early and effective action. A primary example of a tool for USAID’s climate information services efforts is the SERVIR program, a joint development initiative in partnership with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to provide satellite meteorology information and science to partner countries.

Additionally, as the flagship finance initiative under PREPARE, the State Department and USAID, in collaboration with the U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC), have opened an Adaptation Finance Window under the Climate Finance for Development Accelerator (CFDA), which aims to de-risk the development and scaling of companies and investment vehicles that mobilize private finance for climate adaptation.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1: Mobilize private capital through results-based financing such as environmental impact bonds

Results-based financing (RBF) has long been a key component of USAID’s development aid strategy, offering innovative ways to mobilize finance by linking payments to specific outcomes. In recent years, Environmental Impact Bonds (EIBs) have emerged as a promising addition to the RBF toolkit and would greatly benefit as a mechanism for USAID to mobilize and scale novel climate adaptation. Thus, in alignment with the PREPARE plan, USAID should launch an EIB pilot focused on extreme heat through the Climate Finance for Development Accelerator (CFDA), a $250 million initiative designed to mobilize $2.5 billion in public and private climate investments by 2030. An EIB piloted through the CFDA can help unlock public and private climate financing that focuses on extreme heat adaptation solutions, which are sorely needed.

With this EIB pilot, the private sector, governments, and philanthropic investors raise the upfront capital and repayment is contingent on the project’s success in meeting predefined goals. By distributing financial risk among stakeholders in the private sector, government, and philanthropy, EIBs encourage investment in pioneering projects that might struggle to attract traditional funding due to their novel or unproven nature. This approach can effectively mobilize the necessary resources to drive climate adaptation solutions.

This approach can effectively mobilize the necessary resources to drive climate adaptation solutions.

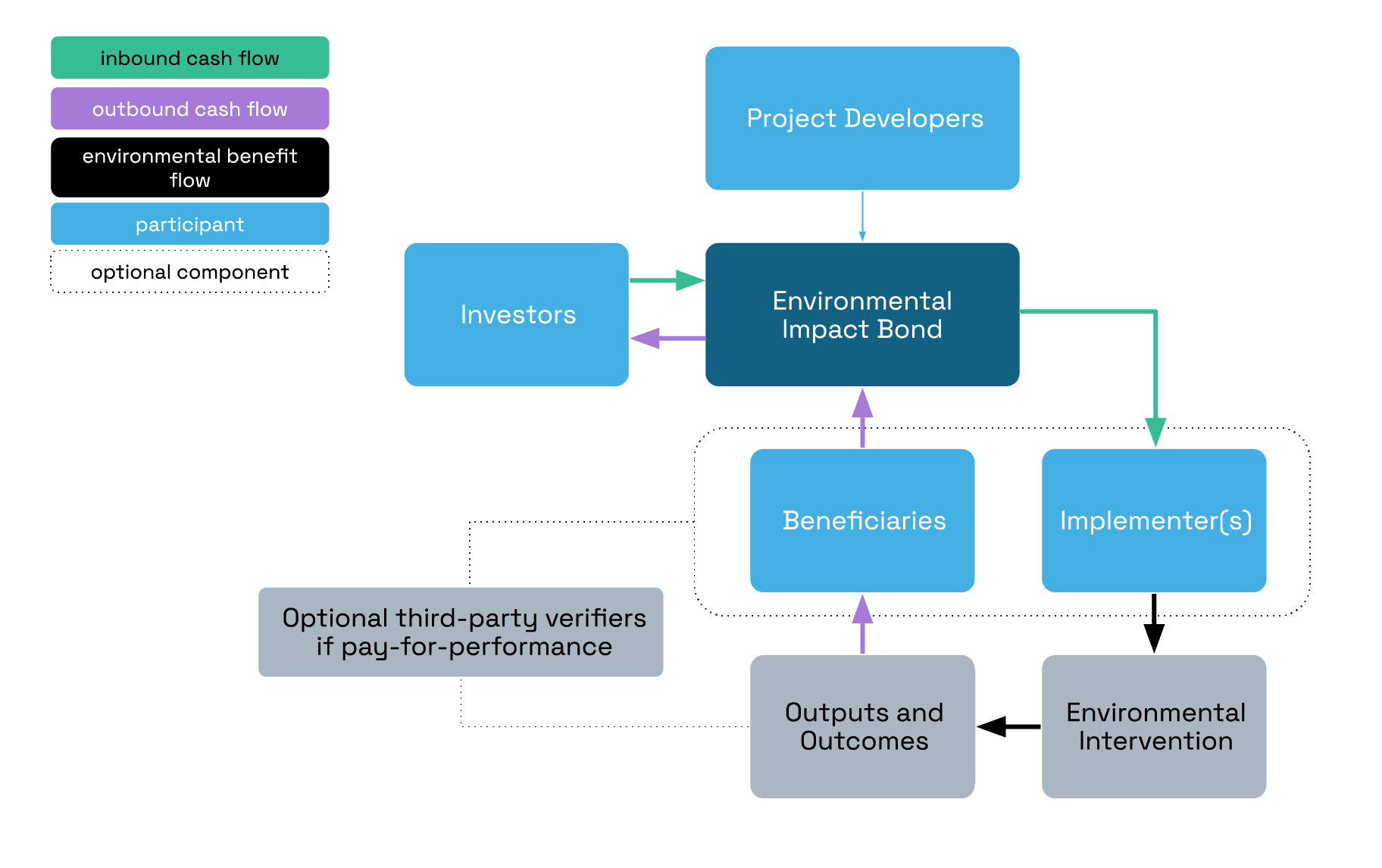

Overview of EIB structure, including cash flow (purple and green arrows) and environmental benefits (black arrows).

Adapted from Environmental Impact Bonds: a common framework and looking ahead

The USAID EIB pilot should focus on scaling projects that facilitate uptake and adoption of affordable and sustainable cooling systems such as solar-reflective roofing and other passive cooling strategies. In Southeast Asia alone, annual heat-related mortality is projected to increase by 295% by 2030. Lack of access to affordable and sustainable cooling mechanisms in the wake of record-shattering heat waves affects public health, food and supply chain, and local economies. An EIB that aims to fund and scale solar-reflective roofing (cool roofs) has the potential to generate high impact for the local population by lowering indoor temperature, reducing energy use for air conditioning, and mitigating the heat island effect in surrounding areas. Indonesia, which is home to 46.5 million people at high risk from a lack of access to cooling, has seen notable success in deploying cool roofs/solar-reflective roofing through the Million Cool Roof Challenge, an initiative of the Clean Cooling Collaborative. The country is now planning to scale production capacity of cool roofs and set up its first testing facility for solar-reflective materials to ensure quality and performance. Given Indonesia’s capacity and readiness, an EIB to scale cool roofs in Indonesia can be a force multiplier to see this cooling mechanism reach millions and spur new manufacturing and installation jobs for the local economy.

To mainstream EIBs and other innovative financial instruments, it is essential to pilot and explore more EIB projects. Cool roofs are an ideal candidate for scaling through an EIB due to their proven effectiveness as a climate adaptation solution, their numerous co-benefits, and the relative ease with which their environmental impacts can be measured (such as indoor temperature reductions, energy savings, and heat island index improvements). Establishing an EIB can be complex and time-consuming, but the potential rewards make the effort worthwhile if executed effectively. Though not exhaustive, the following steps are crucial to setting up an environmental impact bond:

Analyze ecosystem readiness

Before launching an environmental impact bond, it’s crucial to conduct an analysis to better understand what capacities already exist among the private and public sectors in a given country to implement something like an EIB. Additionally working with local civil society organizations is important to ensure climate adaptation projects and solutions are centered around the local community.

Determine the financial arrangement, scope, and risk sharing structure

Determine the financial structure of the bond, including the bond amount, interest rate, and maturity date. Establish a mechanism to manage the funds raised through the bond issuance.

Co-develop standardized, scientifically verified impact metrics and reporting mechanism

Develop a robust system for measuring and reporting the environmental impact projects; With key stakeholders and partner countries, define key performance indicators (KPIs) to track and report progress.

USAID has already begun to incubate and pilot innovative financing mechanisms in the global health space through development impact bonds. The Utkrisht Impact Bond, for example, is the world’s first maternal and newborn health impact bond, which aims to reach up to 600,000 pregnant women and newborns in Rajasthan, India. Expanding the use case of this financing mechanism in the climate adaptation sector can further leverage private capital to address critical environmental challenges, drive scalable solutions, and enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities to climate impacts.

Recommendation 2: USAID should expand the SERVIR joint initiative to include a partnership with NIHHIS and co-develop decision support tools such as an intersectional vulnerability map.

Building on the momentum of Administrator Power’s recent announcement at COP28, USAID should expand the SERVIR joint initiative to include a partnership with NOAA, specifically with NIHHIS, the National Integrated Heat Health Information System. NIHHIS is an integrated information system supporting equitable heat resilience, which is an important area that SERVIR should begin to explore. Expanded partnerships could begin with a pilot to map regional extreme heat vulnerability in select Southeast Asian countries. This kind of tool can aid in informing local decision makers about the risks of extreme heat that have many cascading effects on food systems, health, and infrastructure.

Intersectional vulnerabilities related to extreme heat refer to the compounding impacts of various social, economic, and environmental factors on specific groups or individuals. Understanding these intersecting vulnerabilities is crucial for developing effective strategies to address the disproportionate impacts of extreme heat. Some of these intersections include age, income/socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender, and occupation. USAID should partner with NIHHIS to develop an intersectional vulnerability map that can help improve decision-making related to extreme heat. Exploring the intersectionality of extreme heat vulnerabilities is critical to improving local decision-making and helping tailor interventions and policies to where it is most needed. The intersection between extreme heat and health, for example, is an area that is under-analyzed, and work in this area will contribute to expanding the evidence base.

The pilot can be modeled after the SERVIR-Mekong program, which produced 21 decision support tools throughout the span of the program from 2014-2022. The SERVIR-Mekong program led to the training of more than 1,500 people, the mobilization of $500,000 of investment in climate resilience activities, and the adoption of policies to improve climate resilience in the region. In developing these tools, engaging and co-producing with the local community will be essential.

Recommendation 3: USAID REFS and the State Department Office of Foreign Assistance should work together to develop a mechanism to consistently track and report climate funding flow. This also requires USAID and the State Department to develop clear guidelines on the U.S. approach to adaptation tracking and determination of adaptation components.

Enhancing analytical and data collection capabilities is vital for crafting effective and informed responses to the challenges posed by extreme heat. To this end, USAID REFS, along with the State Department Office of Foreign Assistance, should co-develop a mechanism to consistently track and report climate funding flow. Currently, both USAID and the State Department do not consistently report funding data on direct and indirect climate adaptation foreign assistance. As the Department of State is required to report on its climate finance contributions annually for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and biennially for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the two agencies should report on adaptation funding at similarly set, regular interval and make this information accessible to the executive branch and the general public. A robust tracking mechanism can better inform and aid agency officials in prioritizing adaptation assistance and ensuring the US fulfills its commitments and pledges to support global adaptation to climate change.

The State Department Office of Foreign Assistance (State F) is responsible for establishing standard program structures, definitions, and performance indicators, along with collecting and reporting allocation data on State and USAID programs. Within the framework of these definitions and beyond, there is a lack of clear definitions in terms of which foreign assistance projects may qualify as climate projects versus development projects and which qualify as both. Many adaptation projects are better understood on a continuum of adaptation and development activities. As such, this tracking mechanism should be standardized via a taxonomy of definitions for adaptation solutions.

Therefore, State F should create standardized mechanisms for climate-related foreign assistance programs to differentiate and determine the interlinkages between adaptation and mitigation action from the outset in planning, finance, and implementation — and thereby enhance co-benefits. State F relies on the technical expertise of bureaus, such as REFS, and the technical offices within them, to evaluate whether or not operating units have appropriately attributed funding that supports key issues, including indirect climate adaptation.

Further, announced at COP26, PREPARE is considered the largest U.S. commitment in history to support adaptation to climate change in developing nations. The Biden Administration has committed to using PREPARE to “respond to partner countries’ priorities, strengthen cooperation with other donors, integrate climate risk considerations into multilateral efforts, and strive to mobilize significant private sector capital for adaptation.” Co-led by USAID and the U.S. Department of State (State Department), the implementation of PREPARE also involves the Treasury, NOAA, and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). Other U.S. agencies, such as USDA, DOE, HHS, DOI, Department of Homeland Security, EPA, FEMA, U.S. Forest Service, Millennium Challenge Corporation, NASA, and U.S. Trade and Development Agency, will respond to the adaptation priorities identified by countries in National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and nationally determined contributions (NDCs), among others.

As USAID’s REFS leads the implementation of the PREPARE and hosts USAID’s Chief Climate Officer, this office should be responsible for ensuring the agency’s efforts to effectively track and consistently report climate funding data. The two REFS Centers that should lead the implementation of these efforts include the Center for Climate-Positive Development, which advises USAID leadership and supports the implementation of USAID’s Climate Strategy, and the Center for Resilience, which supports efforts to help reduce recurrent crises — such as climate change-induced extreme weather events — through the promotion of risk management and resilience in the USAID’s strategies and programming.

In making standardized processes to prioritize and track the flow of adaptation funds, USAID will be able to more effectively determine its progress towards addressing global climate hazards like extreme heat, while enhancing its ability to deliver innovative finance and private capital mechanisms in alignment with PREPARE. Additionally, standardization will enable both the public and private sectors to understand the possible areas of investment and direct their flows for relevant projects.

USAID uses the Standardized Program Structure and Definitions (SPSD) system — established by State F — to provide a common language to describe climate change adaptation and resilience programs and therefore enable the comparison and analysis of budget and performance data within a country, regionally or globally. The SPSD system uses the following categories: (1) democracy, human rights, and governance; (2) economic growth; (3) education and social services; (4) health; (5) humanitarian assistance; (6) peace and security; and (7) program development and oversight. Since 2016, climate change has been in the economic growth category and each climate change pillar has separate Program Areas and Elements. The SPSD consists of definitions for foreign assistance programs, providing a common language to describe programs. By utilizing a common language, information for various types of programs can be aggregated within a country, regionally, or globally, allowing for the comparison and analysis of budget and performance data.

Using the SPSD program areas and key issues, USAID categorizes and tracks the funding for its allocations related to climate adaptation as either directly or indirectly addressing climate adaptation. Funding that directly addresses climate adaptation is allocated to the “Climate Change—Adaptation” under SPSD Program Area EG.11 for activities that enhance resilience and reduce the vulnerability to climate change of people, places, and livelihoods. Under this definition, adaptation programs may have the following elements: improving access to science and analysis for decision-making in climate-sensitive areas or sectors; establishing effective governance systems to address climate-related risks; and identifying and disseminating actions that increase resilience to climate change by decreasing exposure or sensitivity or by increasing adaptive capacity. Funding that indirectly addresses climate adaptation is not allocated to a specific SPSD program area. It is funding that is allocated to another SPSD program area and also attributed to the key issue of “Adaptation Indirect,” which is for adaptation activities. The SPSD program area for these activities is not Climate Change—Adaptation, but components of these activities also have climate adaptation effects.

In addition to the SPSD, the State Department and USAID have also identified “key issues” to help describe how foreign assistance funds are used. Key issues are topics of special interest that are not specific to one operating unit or bureau and are not identified, or only partially identified, within the SPSD. As specified in the State Department’s foreign assistance guidance for key issues, “operating units with programs that enhance climate resilience, and/or reduce vulnerability to climate variability and change of people, places, and/or livelihoods are expected to attribute funding to the Adaptation Indirect key issue.”

Operating units use the SPSD and relevant key issues to categorize funding in their operational plans. State guidance requires that any USAID operating unit receiving foreign assistance funding must complete an operational plan each year. The purpose of the operational plan is to provide a comprehensive picture of how the operating unit will use this funding to achieve foreign assistance goals and to establish how the proposed funding plan and programming supports the operating unit, agency, and U.S. government policy priorities. According to the operational plan guidance, State F does an initial screening of these plans.

MDBs play a critical role in bridging the significant funding gap faced by vulnerable developing countries that bear a disproportionate burden of climate adaptation costs—estimated to reach up to 20 percent of GDP for small island nations exposed to tropical cyclones and rising seas. MDBs offer a range of financing options, including direct adaptation investments, green financing instruments, and support for fiscal adjustments to reallocate spending towards climate resilience. To be most sustainably impactful, adaptation support from MDBs should supplement existing aid with conditionality that matches the institutional capacities of recipient countries.

In January 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order (EO 14008) calling upon federal agencies and others to help domestic and global communities adapt and build resilience to climate change. Shortly thereafter in September 2022, the White House announced the launch of the PREPARE Action Plan, which specifically lays out America’s contribution to the global effort to build resilience to the impacts of the climate crisis in developing countries. Nineteen U.S. departments and agencies are working together to implement the PREPARE Action Plan: State, USAID, Commerce/NOAA, Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Treasury, DFC, Department of Defense (DOD) & U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), International Trade Administration (ITA), Peace Corps, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Energy (DOE), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Department of Transportation (DOT), Health and Human Services (HHS), NASA, Export–Import Bank of the United States (EX/IM), and Department of Interior (DOI).

Congress oversees federal climate financial assistance to lower-income countries, especially through the following actions: (1) authorizing and appropriating for federal programs and multilateral fund contributions, (2) guiding federal agencies on authorized programs and appropriations, and (3) overseeing U.S. interests in the programs. Congressional committees of jurisdiction include the House Committees on Foreign Affairs, Financial Services, Appropriations, and the Senate Committees on Foreign Relations and Appropriations, among others.

Using Trade to Build Stability in South Asia

Former Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto once said, “If India builds the bomb, Pakistan will eat grass, even go hungry, but we will get our own.”1 Today, Pakistan has had the bomb for more than 13 years2, yet according to expert estimates the Pakistanis are building nuclear weapons faster than anyone else in the world.3 Meanwhile, Pakistan’s economy continues to deteriorate at such a rate that its people resorting to grass as sustenance may actually become a reality. Economists forecast that Pakistan’s GDP must expand at a minimum of 3 percent just to maintain current living standards and keep up with the rapidly expanding population.4

With the rapid spread of Islamic extremism and tensions growing daily between the civilian government, the courts, and the military, the prospect of an increasing number of nuclear weapons in Pakistan sparks fear that one of these weapons could fall into the wrong hands. Given the risks involved with a destabilized Pakistan, there is an obvious and pressing need to improve the security situation in South Asia, a region home to nearly one-fifth of the world’s population.

The tensions between India and Pakistan date back to their partition in 1947 into separate countries. Since then, the two have fought a total of four wars, mostly over the disputed territory of Kashmir. Pakistan has been suspected of supporting a militant insurgency in Indian administered Kashmir since the mid-1980s, while India is alleged to support an insurgency in Pakistan’s Balochistan Province.5 This strained relationship prompted the development of both countries’ nuclear weapons programs, while security concerns on Pakistan’s western and eastern borders – partly a legacy of Pakistani and U.S. support for militants along its western frontier during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 19796 – have led to disproportionate military influence in Pakistan’s politics and administration. As a result, the country has experienced three periods of military dictatorship, which have severely limited the country’s ability to build and maintain viable democratic institutions.7

Given the bleak situation between India and Pakistan is it even possible to build better relations? Improving bilateral trade is one way to potentially foster collaboration between the two states, but the last 65 years have demonstrated how difficult it is for India and Pakistan to make progress on security related issues. Kashmir remains in dispute: thousands of Indian and Pakistani soldiers remain perched high on the Siachen Glacier, a desolate piece of ice where more soldiers die from avalanches than enemy fire. Nevertheless, there remains a real threat that conflict can erupt anytime at Siachen, the world’s highest battlefield. Simultaneously, a significant portion of Indian and Pakistani society remains marred in poverty. The collaboration required to build better trade relations has the potential to positively impact the situation of both countries and perhaps bring India and Pakistan closer together.

South Asia Today

India and Pakistan face precarious times: millions remain in poverty on both sides of the border, as both countries face deteriorating rates of economic growth. Pakistan is forecasted to miss its target of 4.2 percent GDP growth rate this year, while India has had to cut its GDP growth forecast to 5 percent.89 At the same time, a continuing population boom means that this modest economic growth will most likely not be enough to improve upon or even maintain the quality of life for Indians and Pakistanis. With the anticipated U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in December 2014 there is additional potential for instability in the region, as a reduction in Western engagement could spark greater unrest in the tribal belt separating Pakistan and Afghanistan. Instability and violence from this region could spread to the rest of Afghanistan and Pakistan, ultimately negatively impacting India as well.

Improving trade relations and engaging in greater trade could be a way for India and Pakistan to improve their economies. Although the situation they face is not promising, the domestic political situation in both countries suggests that now is the best time to make improvements in trade relations a reality. With the May 11,2013 Pakistani elections, Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) has returned to power with a solid parliamentary majority.10 Sharif has already indicated his support for improved bilateral trade relations, reaching out to his Indian counterpart Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, and inviting him to visit Pakistan.11 Similarly, Singh has also expressed his intention to build better relations with Pakistan, specifically focusing on greater trade.12 While these are promising signs for bilateral relations, it remains to be seen whether these two leaders will follow these initial overtures with real progress. Although Sharif launched a series of ambitious economic reforms during his first term, his previous two terms in office were characterized by corruption.13Singh’s government has also seen several major corruption scandals, as well as an inability to implement key economic reforms such as further liberalization of the Indian economy to encourage foreign investment.14

However, both leaders are under pressure to improve their domestic economic situation. Pakistanis elected Sharif with a wide margin of support, but will quickly become impatient if he does not deliver on his promise to improve the economic situation. Across the border in India, Singh and his Indian National Congress (INC) face parliamentary election in 2014 – signs of economic progress and reform are vital if they are to be reelected. Meanwhile, the INC’s main opposition, the Bharatya Janta Party (BJP), recently experienced a setback by losing a critical state election in Karanataka.15 Despite this, Singh and his government are still under immense pressure to improve India’s economy. Because of these domestic political situations, inaction on improving the economy is a risk that neither Nawaz Sharif nor Manmohan Singh can afford to take. Greater bilateral trade is one policy that both Sharif and Singh can adopt to improve the economies of their countries.

To boost trade from current levels, India and Pakistan must take several key steps.

1) Develop a uniform, jointly developed trade policy

Different policies govern trade at the Punjab crossing, the two Kashmiri crossings, and by sea – a common trade policy governing what goods can be traded and how trade is conducted across the various routes between India and Pakistan does not yet exist. The two countries need to establish a clear joint trade policy that outlines how present trade policies between India and Pakistan will evolve in the coming years, so that ultimately the same trade policies and practices are in place regardless of the border crossing used.

2) Pakistan must grant MFN status to India

Setting a clearer and more cohesive bilateral trade policy depends on Pakistan extending “Most Favored Nation” status to India. MFN status is important in international trade because it means that one country will not discriminate against another country in terms of trade. India has granted Pakistan MFN status since 1996. Pakistan granted India MFN status briefly in 2011, but then retracted India’s MFN status due to opposition from several key domestic industries such as agriculture and automotive sectors. Granting India MFN status would mean that Pakistan must extend the same trade preferences to India as Pakistan currently does to other countries that it has granted MFN status.

To avoid retracting this MFN status as it did in 2011, Pakistan and India must adopt a gradual process with a concrete timeline, with the ultimate goal to extend MFN status to India. The gradual process of extending MFN status could be incorporated into the overall objective of developing a clear, unified Indo-Pakistan trade policy. With a clear timeline, domestic industries in Pakistan that could be adversely affected by liberalization of trade with India have a chance to prepare and adjust to these economic shifts. To take this preparation a step further, the two countries should establish cross-border collaboration in sectors that would be the hardest hit from further Indo-Pakistan trade liberalization. Through these joint collaborations, businessmen from both countries could work together to manage the impact of extending MFN status to India. Altogether, these steps would minimize the pain felt by those who would lose out from Indo-Pakistan trade liberalization.

3) Improve infrastructure linking India and Pakistan

Pakistan and India need to improve the infrastructure connecting the two countries. From extensive delays at the seaports to poor cross border road infrastructure in Kashmir, inadequate trade infrastructure is common to all routes connecting India and Pakistan.16 To relieve strain on existing connections the two countries could open up more border crossings. Ideally, these crossings would be built with Integrative Check Posts (ICP), similar to the existing one at Wagah in Punjab. The ICP is a 120 acre facility that significantly expanded the customs and inspection facilities on the India side of the Wagah-Attari border crossings,17 allowing trade traffic between India and Pakistan to increase from 100-150 trucks per day to about 250 trucks per day.1819

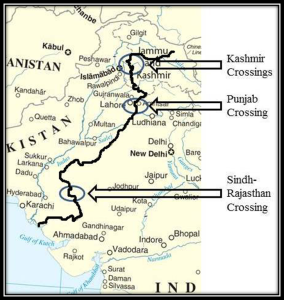

Indo-Pakistan Trade across the Line of Control in Kashmir20

At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that infrastructure improvements need to take place on both sides of the border to make them effective. Although the ICP at Wagah has increased processing capacity, no comparable improvement infrastructure has taken place on the Pakistani side of the Wagah crossing, and the true benefits of improved infrastructure will only be realized when improvements are implemented on both sides of the border. In addition to physical infrastructure, the two countries also need to build up banking and legal institutions. The virtual absence of these two components has made trade in Kashmir risky and difficult to accomplish. Building these vital linkages will ensure that future growth in Indo-Pakistan trade is sustainable.

4) Improve ties between the Indian and Pakistani business communities

India and Pakistan need to improve coordination between business communities on both sides of the border. The joint Chamber of Commerce in Kashmir was successful at linking the two business communities together, even though it has not been as successful as intended for its initial purpose of liberalizing cross-Line of Control trade.21 The governments of India and Pakistan need to expand these types of business oriented organizations in places like Punjab, Sindh and Gujarat.

Dried Date Merchant, Karachi, Pakistan22

Dubai, the UAE and other third party countries currently function as meeting grounds for the Indian and Pakistani business community. This is due to the fact that it is easier to travel to these third party countries than to go across the shared border. Additionally, Indo-Pakistan trade often flows through these indirect routes to circumvent the restrictive and often convoluted trade regulations across the Indo-Pakistani border. While India and Pakistan work to build better direct trade relations, they could engage members of the Pakistani and Indian business communities by establishing organizations to facilitate interaction between them. Eventually, as relations improve, these organizations could help expedite the shift of Indo-Pakistan trade back from these third party locations.

Conclusion

Imposing greater Indo-Pakistan trade solely through policy will not be sustainable in the long run. Rather, India and Pakistan must use policy to craft an environment where trade can freely occur. However, this trade will only be sustainable if there is greater cultural awareness between the people of the two countries. A prominent businessman from Kutch in Gujarat once asked me, “Why should we trade with those terrorists?” Only when Indians and Pakistanis break away from such false perceptions can trade truly evolve into a long-term road to lasting peace.

Ravi Patel is a student at Stanford University where he recently completed a B.S. in Biology and is currently pursuing an M.S. in Biology. He completed an undergraduate honors thesis on developing greater Indo-Pakistan trade under Sec. William Perry at the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC). Patel is the founder and president of a student to student collaborative research program connecting leading Pakistani and American university students and also the president of a similar organization called the Stanford U.S.-Russia Forum which connects university students in Russia and the United States. In the summer of 2012, Patel was a security scholar at the Federation of American Scientists. He also has extensive biomedical research experience focused on growing bone using mesenchymal stem cells through previous work at UCSF’s surgical research laboratory and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.