India’s SSBN Shows Itself

|

| A new satellite image appears to show part of India’s new SSBN partly concealed at the Visakhapatnam naval base on the Indian east coast (17°42’38.06″N, 83°16’4.90″E). |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

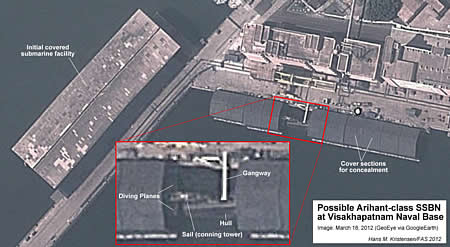

Could it be? It is not entirely clear, but a new satellite image might be showing part of India’s first nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine, the Arihant.

The image, taken by GeoEye’s satellite on March 18, 2012, and made available on Google Earth, shows what appears to be the conning tower (or sail) of a submarine in a gap of covers intended to conceal it deep inside the Visakhapatnam (Vizag) Naval Base on the Indian east coast.

The image appears to show a gangway leading from the pier with service buildings and a large crane to the submarine hull just behind the conning tower. The outlines of what appear to be two horizontal diving planes extending from either side of the conning tower can also be seen on the grainy image.

The Arihant was launched in 2009 from the shipyard on the other side of the harbor and moved under an initial cover. An image released by the Indian government in 2010 appears to show the submarine inside the initial cover.

|

| The Indian government published this image in 2010, apparently showing the Arihant inside the initial concealment building. |

.

The new cover, made up of what appears to be 13-meter floating modules that can be assembled to fit the length of the submarine, similarly to what Russia is using at its submarine shipyard in Severodvinsk, first appeared in 2010. Images from 2011 show the modules in various configurations but without the submarine inside.

The movement of the Arihant from the initial cover building to the module covers next to the service facilities and large crane indicates that the submarine has entered a new phase of fitting out. The initial cover building appeared empty in April 2012 when the Indian Navy show-cased its new Russia-supplied Akula-class nuclear-powered attack submarine: the Chakra.

It is thought that the Arihant is equipped with less than a dozen launch tubes behind the conning tower for short/medium-range nuclear-armed ballistic missiles. Before it can become fully operational, however, the Arihant will have to undergo extensive refitting and sea-trials that may last through 2013. It is expected that India might be building several SSBNs.

Like the other nuclear weapon states, India continues to modernize its nuclear forces, despite pledges to work for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See also: Indian nuclear forces, 2012.

New Nuclear Notebook: Indian Nuclear Forces, 2012

|

| The Indian government says its first nuclear ballistic missile submarine – the Arihant – will be “inducted” in mid-2013, a term normally meaning delivered to the armed forces. Several boats are thought to be under construction. Image: Government of India |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris

Our latest Nuclear Notebook has been published by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. We estimate that India currently has 80-100 nuclear warheads for its emerging Triad of air-, land-, and sea-based nuclear-capable delivery vehicles.

The latest test launch of a nuclear-capable ballistic missile occurred yesterday when an Agni I missile was launched by the Strategic Forces Command from a road-mobile launcher at the missile test launch center on Wheeler Island on India’s east coast in what the Indian government described as a “training exercise to ensure preparedness.”

|

| India’s east coast missile test launch center has been expanded with a second launch pad since 2003. Click image for larger version. |

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Indian Army Chief: Nukes Not For Warfighting

|

| Gen. V.K. Singh |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

India’s nuclear weapons “are not for warfighting,” the chief of India’s army said Sunday at the Army Day Parade. The weapons have “a strategic capability and that is where it should end,” General V. K. Singh declared.

The rejection of nuclear warfighting ideas is a welcoming development in the debate over the role of nuclear weapons in South Asia. Pakistan’s military’s description of its new snort-range NASR missile as a “shoot and scoot…quick response system” has rightly raised concerns about the potential early use of nuclear weapons in a conflict.

NASR is one of several new nuclear weapon systems that are nearing deployment with warheads from a Pakistani stockpile that has nearly doubled since 2005.

India is also increasing its arsenal and already has short-range missiles with nuclear capability: the land-based Prithvi has been in operation for a decade, and a naval version (Dhanush) is under development. But India’s posture seems focused on getting its medium-range Agni II in operation, developing longer-range versions to target China, and building a limited submarine-based nuclear capability.

If Gen. Singh’s rejection of nuclear warfighting is reflected in India’s future nuclear posture, two important things will have been achieved: rejection of the mindless tit-for-tat philosophy that otherwise dominates nuclear posturing; and limiting the scenarios where nuclear weapons otherwise could come into use. The rejection also has importance for other nuclear weapon states, where some have called for making nuclear weapons more “tailored” to limited regional scenarios.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

DF-21C Missile Deploys to Central China

|

| China’s new DF-21C missile launcher shows itself in Western China. Image: GoogleEarth |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest Pentagon report on Chinese military forces recently triggered sensational headlines in the Indian news media that China had deployed new nuclear missiles close to the Indian border.

The news reports got it wrong, but new commercial satellite images reveal that launch units for the new DF-21C missile have deployed to central-western China.

New DF-21C Launch Units

Analysis of commercial satellite imagery reveals that launch units for the road-mobile DF-21C medium-range ballistic missile now deploy several hundred kilometers west of Delingha in the western part of central China.

| Location of DF-21C Launch Units |

|

| For larger versions of the two middle satellite images, click here and here. Images: GoogleEarth and chinamil.com.cn |

In one image, taken by the GeoEye-1 satellite on June 14, 2010, two launch units are visible in approximately 230 km west of Delingha. The units are dug into the dry desert slopes near Mount Chilian along national road G215. Missile launchers, barracks, maintenance and service units are concealed under large dark camouflage, which stands out clearly in the brown desert soil.

The eastern launch unit (38° 6’37.75″N, 94°59’2.19″E) includes a central area with red barracks clearly visible below the camouflage, which probably also covers logistic units such as communications vehicles, fuel trucks, and personnel carriers. An 88×17 meter garage of brown camouflaged probably covers the launcher service area, with five 15-meter garages nearby probably housing the TELs. Approximately 130 meters north of the central area, brown camouflage and dirt barriers possibly house the unit’s remote fuel area. Two launch pads are visible, one only 180 meters from the main section, the other on the access road leading to national road G215.

The western launch unit (38° 9’32.82″N, 94°55’37.02″E) is located approximately 7 km further west about 2.4 km to the north of national road G215. The unit consists of four sections: personnel barracks (almost 100 with more possibly under camouflage); a logistic vehicles area; a launcher service area with a 90×33 meter camouflage and four garages; and what is possibly a remote fuel storage area. A launch pad is located along the access road close to G215.

The satellite image shows what appears to be a DF-21C entering or leaving the camouflaged launcher service area. The characteristic nose cone of the missile canister embedded into the rear of the driver cockpit is clearly visible, with the rest of launcher probably covered by a tarp.

This is, to my knowledge, the first time that the DF-21C has been identified in a deployment area. In 2007, I used commercial satellite images to describe the first visual signs of the transition from DF-4 to DF-21 at Delingha. A second article in 2008 described the extensive system of launch pads that extends west from Delingha along national road G215 past Da Qaidam.

There are five launch pads within five miles of the two launch units, with dozens other pads along and north of G215 in both directions.

More Invulnerable but with Limits

China’s ongoing modernization from old liquid-fuel missiles to new solid-fuel missiles is getting a lot of attention. The new systems are more mobile and thus less vulnerable to attack. Yet the satellite images also give hints about limitations.

First, the launch units are large with a considerable footprint that covers an area of approximately 300×300 meters. They are manpower-intensive requiring large numbers of support equipment. This makes them harder to move quickly and relatively easy to detect by satellite images.

| DF-21C Launch Unit on the Move |

|

| The DF-21C medium-range ballistic missile may be more mobile and harder to target than older missiles, but it still relies on a large support unit that can be detected. Image: CCTV-7 |

.

Individual launchers of course would be dispersed into the landscape in case of war. But although the road-mobile launcher has some off-road capability, it requires solid ground when launching to prevent damage from debris kicked up by the rocket engine. As a result, launchers would have to stay on roads or use the pre-made launch pads that stand out clearly in high-resolution satellite images. Moreover, a launcher would not simply drive off and launch by itself, but need to be followed by support vehicles for targeting, repair, and communication.

Indian News Media (Mis)reporting

The deployment of DF-21 missiles caused constipation in Indian last month after the 2010 Pentagon report of Chinese military forces stated that China is replacing DF-4 missiles with DF-21 missiles to improve regional deterrence. The statement was contained in a section dealing with Chinese-Indian affairs and was picked up by the Press Trust of India, which mistakenly reported that the Pentagon report stated that, “China has moved advanced longer range CSS-5 [DF-21] missiles close to the border with India.” The Times of India even wrote the missiles were being deployed “on border” with India.

| India News Media Makes a Bad Situation Worse |

|

| The India news media significantly misreported what the Pentagon report said about the Chinese DF-21 deployment. Not the finest hour of Indian journalism. |

.

Not surprisingly, the misreporting triggered dramatic news articles in India, including rumors that the Indian Strategic Forces Command was considering or had already moved nuclear-capable missile units north toward the Chinese border in retaliation.

The Pentagon report, however, said nothing about moving DF-21 missiles close to or “on” the Indian border. Here is the actual statement: “To improve regional deterrence, the PLA has replaced older liquid-fueled, nuclear-capable CSS-3 intermediate-range ballistic missiles with more advanced and survivable solid-fueled CSS-5 MRBM….” The statement echoes a statement in the 2009 report: “The [People’s Liberation Army] has replaced older liquid-fueled nuclear-capable CSS-3 [DF-4 medium-range ballistic missiles] MRBMs with more advanced solid-fueled CSS-5 MRBMs in Western China.”

The sentence appears to describe the apparent near-completion of China’s replacement of DF-4 missiles with DF-21 missiles, probably at two army base areas in Hunan and Qinghai provinces, a transition that has been underway for two decades. The two deployment areas are each more than 1,500 kilometers from the Indian border.

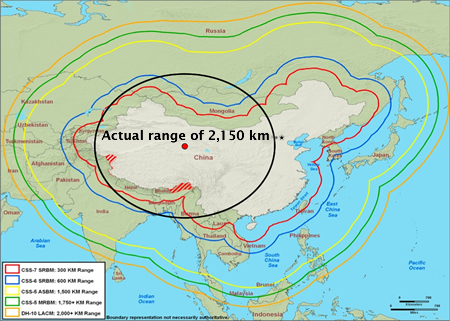

Range Confusion

The unclassified ranges of Chinese DF-21 versions published by the U.S. intelligence community are 1,770+ km (1,100+ miles) for the two nuclear versions (DF-21, CSS-5 Mod 1; and DF-21A, CSS-5 Mod 2). The DF-21A appears to have an extended range of 2,150 km. The dual-capable “conventional” DF-21C has a maximum range of 1,770 km, and the yet-to-be-deployed DF-21D anti-ship missile has a shorter range of 1,450+ km. Private publications frequently credit the DF-21D with a much longer range (CSBA: 2,150 km; sinodefence.com and Wikipedia: 3,000 km).

DOD maps are misleading because they depict missile ranges measured from the Chinese border, as if the launchers were deployed there rather than at their actual deployment areas far back from the border. The 2008 report, for example, includes a map essentially showing China’s border extended outward in different colors for each missile range. The result is a DF-21 range of about 3,000 km if measured from the actual deployment areas.

| DF-21 Range According to 2008 Pentagon Report |

|

| The 2008 Pentagon report on China’s military forces misrepresents missile ranges. |

.

The 2010 report is even worse because it shows the ranges without the border contours as circles but measured from the most extreme border position. The result is a map that is even more misleading, suggesting a DF-21 range of as much as 3,500 km from actual deployment areas. The actual maximum range is 2,150 km for DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2), and 1,770 km for the DF-21C.

| DF-21 Range According to 2010 Pentagon Report |

|

| The 2010 Pentagon report on Chinese military issues greatly exaggerates the reach of the DF-21 by drawing a ring around China that doesn’t reflect actual deployment areas. |

.

Although a DF-21 launcher could theoretically drive all the way up to the border to launch, the reality is that DF-21 bases and roaming areas are located far back from the border to protect the fragile launchers from air attack. DOD maps should reflect that reality.

Additional Resources: earlier China blogs; Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

India and Pakistan: Whose is Bigger?

|

| India-Pakistan nuclear competition on display again |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

If Indian news reports (here, here, and here) are any indication, India has once again discovered that Pakistan might possess a few nuclear weapons more than India.

This time the reports are based on an article Robert Norris and I published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, in which we provide estimates for the number of nuclear weapons in the world.

In 2009, our report on Pakistan’s nuclear forces triggered a statement from the chief of the Indian army that if the warhead estimate in our report was correct then Pakistan had moved beyond what is needed for deterrence. The unintended acknowledgement: so had India.

In 2008, reports about the arrival of the first Chinese Jin-class SSBN at a naval base on Hainan Island were followed by suggestions that India needed to build perhaps five new Arihant-class ballistic missile submarines.

As far as I can gauge, apart from nuclear testing where India started first, Pakistan has always been a little ahead in warheads, fissile material, and delivery systems. But neither country can claim any nuclear moral high ground; both are increasing their nuclear arsenals, both are producing more fissile material for nuclear weapons, and both are diversifying the means to deliver nuclear weapons and extending their range.

The two countries are now at a warhead level about equal to that of Israel (~80 warheads). But whereas it took Israel 40 years to reach that level, India and Pakistan have done so in only 12 years. And they’re apparently not done.

Although neither government wants to say so publicly, India and Pakistan are in effect in a nuclear arms race. It might not be of the intensity of the Cold War arms race between the Soviet Union and the United States, but it is a race nonetheless for capability and systems. Pointing to the other side having more only underscores that dynamic.

Indian and Pakistani security will probably be served better by trying soon to define just how big a nuclear force is sufficient for minimum deterrence so that “prudent planning” doesn’t take them to a new and more dangerous level.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Estimated Nuclear Weapons Locations 2009

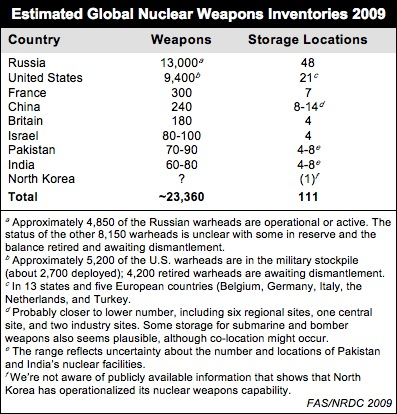

Some 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at 111 locations around the world

.The world’s approximately 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at an estimated 111 locations in 14 countries, according to an overview produced by FAS and NRDC.

Nearly half of the weapons are operationally deployed with delivery systems capable of launching on short notice.

The overview is published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and includes the July 2009 START memorandum of understanding data. A previous version was included in the annual report from the International Panel of Fissile Materials published last month.

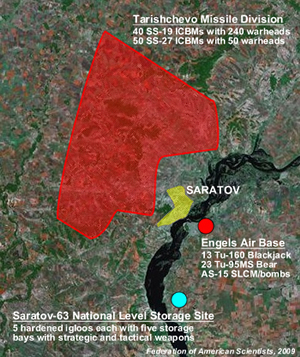

More than 1,000 nuclear weapons surround Saratov.

Russia has an estimated 48 permanent nuclear weapon storage sites, of which more than half are on bases for operational forces. There are approximately 19 storage sites, of which about half are national-level storage facilities. In addition, a significant number of temporary storage sites occasionally store nuclear weapons in transit between facilities.

This is a significant consolidation from the estimated 90 Russian sites ten years ago, and more than 500 sites before 1991.

Many of the Russian sites are in close proximity to each other and large populated areas. One example is the Saratov area where the city is surrounded by a missile division, a strategic bomber base, and a national-level storage site with probably well over 1,000 nuclear warheads combined (Figure 2).

The United States stores its nuclear weapons at 21 locations in 13 states and five European countries. This is a consolidation from the estimated 24 sites ten year ago, 50 at the end of the Cold War, and 164 in 1985 (see Figure 3).

Approximately 50 B61 nuclear bombs inside an igloo at what might be Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. Seventy-five igloos at Nellis store “one of the largest stockpile in the free world,” according to the U.S. Air Force, one of four central storage sites in the United States.

Europe has about the same number of nuclear weapon storage locations as the Continental United States, with weapons scattered across seven countries. This includes seven sites in France and four in Britain. Five non-nuclear NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey) still host U.S. nuclear weapons first deployed there during the Cold War.

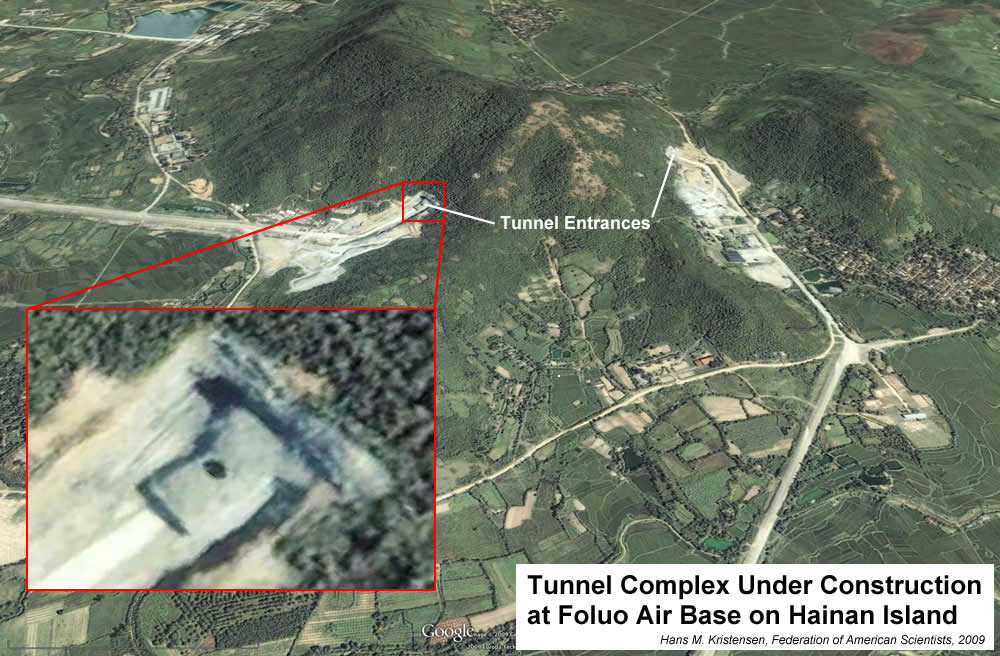

We estimate that China has 8-14 facilities associated with nuclear weapons, most likely closer to the lower number, near bases with units that operate nuclear missiles or aircraft. None of the weapons are believed to be fully operational but stored separate from delivery vehicles at sites controlled by the Central Military Commission.

Where does China store nuclear warheads for its ballistic missile submarines? The naval base near Julin on Hainan Island has extensive underground facilities. An alternative to the base itself could potentially be a facility elsewhere on the island, such as Foluo Air Base where construction of an underground facility began five years before the first SSBN arrived at Hainan. Or are the weapons stored on the mainland? Click image to enlarge.

Israel probably has about four nuclear sites, whereas the nuclear storage facilities in India and Pakistan are – despite many rumors – largely undetermined. All three countries are thought to store warheads separate from delivery vehicles.

Despite two nuclear tests and many rumors, we are unaware of publicly available evidence that North Korea has operationalized its nuclear weapons capability.

Warhead concentrations vary greatly from country to country. With 13,000 warheads at 48 sites, Russian stores an average of 270 warheads at each location. The U.S. concentration is much higher with an average of 450 warheads at each location. These are averages, however, and in reality the distribution is thought to be much more uneven with some sites only storing tens of warheads.

Finally, a word of caution is in order: estimates such as these obviously come with a great deal of uncertainty, as we don’t have access to classified intelligence estimates. Based on publicly available information and our own assumptions we have nonetheless produced a best estimate that we hope will assist the public debate. Comments and suggestions are encouraged so we can adjust the overview in the future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Air Force Intelligence Report Available

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Air Force Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published an update to its Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat. The document, which I obtained from NASIC, is sobering reading.

The latest update continues the previous user-friendly format and describes a number of important assessments and new developments in ballistic and cruise missiles of many of the world’s major military powers.

The report also helps dispel many web-rumors that have circulated about Chinese, Russian, Indian and Pakistani nuclear forces.

In this blog I’ll focus on the nuclear weapon states, particularly China.

Chinese Nuclear Forces

As the DF-3A retirement continues (there are now only 5-10 launchers left of close to 100 in the 1980s), the liquid-fuel missile is being replaced by a family of solid-fuel DF-21 variants. The NASIC identifies four, including two nuclear versions (Mod 1 and Mod 2), one conventional version, and an anti-ship version that unlike the others is not yet deployed.

Thankfully, the report dispels widespread speculation by web sites, news media, and even Jane’s after images began circulating on the Internet, that a DF-25 had been deployed, some even said with three nuclear warheads. But it was, as I predicted last year and NASIC now confirms, in fact a DF-21.

|

DF-21 Road-Mobile Launchers |

|

| A column of DF-21s on the road in what could be the Delingha deployment are in Qinghai Province. Several of the vehicles have identical camouflage patterns, raising suspicion that the image has been manipulated. Four DF-21 versions exist, two nuclear, one conventional, and one anti-ship version. Image: Web |

.

The report also reaffirms that the first of the DF-31s and DF-31As “have been deployed to units within the Second Artillery Corps,” and NASIC estimates that “less than 15” are deployed, up from the “less than 10” estimate in the Pentagon’s March 2009 report (which actually used 2008 data).

The NASIC report states that neither of China’s two types submarine-launched ballistic missiles is operational. This suggests that the multi-year overhaul of the JL-1 equipped Xia SSBN, which was completed last year, was not successful. The successor missile JL-2 for the new Jin-class SSBNs has not reached operational status either. NASIC gives the JL-2 the U.S. designation CSS-NX-14, not a numerical follow-on to the JL-1, which is listed as CSS-NX-3. The “14” could be a typo, but it appears several places in the report. The JL-2 is shown to have roughly the same dimensions as the Russian SS-N-32 SLBM.

NASIC lists single warheads on all of the Chinese missiles, not multiple warheads as speculated by many. “China could develop MIRV payloads for some of its ICBMs,” the report states. Yet it also predicts that, “Future ICBMs probably will include some with multiple independently-targetable reentry vehicles.” Whether that prediction – which appears to hint that China has more ICBMs under development – comes true remains to be seen, and the U.S. intelligence community has stated for years that one development that could trigger it is a U.S. ballistic missile defense system.

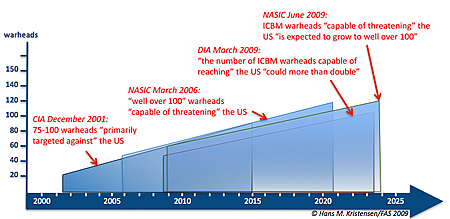

The report echoes recent statements from other branches of the U.S. intelligence community that the number of warheads on Chinese ICBM capable of reaching the United States could expand to “well over 100 in the next 15 years.” Unfortunately, “well over 100” can mean anything so it is hard to compare this NASIC’s projection with the CIA projection from 2001 of 75-100 warheads “primarily targeted against the United States” by 2015. That projection only included DF-5A and DF-31A capable of targeting all of the United States, with the high number requiring multiple warheads on DF-5A. But the timeline for the anticipated increase has slipped considerably from 2015 to 2024.

.

Moreover, ICBMs “primarily targeted against the United States” is a smaller group of missiles than those “capable of reaching the United States,” which currently includes about 60 DF-4, DF-5A, DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs with as many warheads. For this group to grow to “well over 100 warheads” suggests that NASIC anticipates that China will deploy at least 60-70 DF-31, DF-31A and JL-2 missiles by 2024 (the DF-4 will probably have been retired by then). Assuming that includes 36 JL-2s on three Jin-class SSBNs, an additional 20-30 total DF-31s and DF-31As would have to be deployed to reach 120 ICBM warheads. If five SSBNs were deployed, then only 10 additional land-based ICBMs would be required, or 30 if the 20 DF-5As were retired.

The DH-10 land-attack cruise missile is listed as “conventional or nuclear,” the same designation used for the nuclear and conventional Russian AS-4. But unlike the 2009 DOD report on Chinese military forces, which lists 150-350 DH-10s deployed with 40-50 launchers, NASIC lists the operational status as “undetermined.”

Russian Nuclear Forces

NASIC states that “Russia retains about 2,000 warheads on ICBMs,” which is far too many for the land-based ICBM force and so probably includes SLBMs as well. The ICBM force will continue to decrease due to arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints. Even so, “Russia will probably retain the largest ICBM force outside the United States,” and “most of these missiles are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order,” according to NASIC.

|

|

The multiple-warhead RS-24 ICBM is, according to NASIC, not a new missile but a modified version of the SS-27 (Topol-M). |

The NASIC report formally designates the “multiple” warhead RS-24 ICBM to be a modification of the SS-27 Mod 1. This has some significance because Russia under START is not allowed to increase the warhead loading on missiles declared under the treaty, but in anticipation of the treaty expiring in December 2009 apparently has been working on doing so anyway. The RS-24, which will exist in both silo and road-mobile versions, is not yet deployed but Russian military officials have said this will happen in December.

On the submarine force the modified SS-N-23 known as Sineva is listed as carrying the same number of warheads (4) as the original version, far less than the “up to 10” listed by NASIC in 2006 and by Russian news media. The range is listed as the usual 8,000+ km even though the Russian Navy claimed in October 2008 to have test-flown the missile to 11,547 km. NASIC also continues to list two remaining Typhoon-class SSBNs as capable of carrying the SS-N-20, even though the missile is reported to have been withdrawn from service. I suspect this is because the report uses START-counted missile tubes. A third Typhoon SSBN has been converted as a test platform for the SS-N-32/Bulava-30, and NASIC lists this submarine with 20 tubes for the new missile.

Interestingly, the kh-102 cruise missile, a replacement for the AS-15 long rumored to be under development, is not listed by NASIC.

Indian Nuclear Forces

Even though Indian news media reports and private/corporate institutes have reported for years that Agni I and Agni II were deployed, the NASIC report shows that operational deployment of the road-mobile Agni I SRBM has only recently begun, with “fewer than 25” missile launchers deployed. NASIC seems to back our assessment from last year that the Agni II at that time was not yet fully operational, by listing “fewer than 10” launchers deployed.

Two short-range sea-based ballistic missiles are under development: Dhanush and Sagarika. Neither is operational yet, and NASIC safely estimates that the Sagarika will become operational sometime after 2010.

Despite Indian news media reports of development of a nuclear-capable cruise missile, no mentioning of such a weapon system is made by NASIC.

Pakistani Nuclear Forces

There are fewer than 50 launchers for the road-mobile Ghaznavi and Shaheen I SRBMs listed in the NASIC report, and the 2,000+ km Shaheen II MRBM is not yet operational but may be soon. Pakistan also appears to have two nuclear-capable cruise missiles under development: the ground-launched Babur and the air-launched Ra’ad.

Other Nuclear Weapon States

Although “friendly” nuclear weapon states are not included because they are not a “threat” to the United States, the report’s section on cruise missiles is nonetheless interesting because it – unlike the ballistic missile sections – describes weapon systems of “friendly” nuclear weapon states such as France and Israel. Yet nuclear systems, such as the French ASMP-A, are excluded. Israeli submarine-based cruise missiles, which have been rumored to have nuclear capability (I’m not convinced), are not included either.

Curiously, even after two nuclear tests and the intelligence community stating for more than a decade that North Korea has nuclear weapons, the NASIC report does not list any of North Korea’s weapons as “nuclear” or “conventional or nuclear.” That is, I think, interesting.

Background Information: 2009 NASIC report | Previous NASIC reports

Russian Tactical Nuclear Weapons

|

| New low-yield nuclear warheads for cruise missiles on Russia’s submarines?. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two recent news reports have drawn the attention to Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons. Earlier this week, RIA Novosti quoted Vice Admiral Oleg Burtsev, deputy head of the Russian Navy General Staff, saying that the role of tactical nuclear weapons on submarines “will play a key role in the future,” that their range and precision are gradually increasing, and that Russia “can install low-yield warheads on existing cruise missiles” with high-yield warheads.

This morning an editorial in the New York Times advocated withdrawing the “200 to 300” U.S. tactical nuclear bombs deployed in Europe “to make it much easier to challenge Russia to reduce its stockpile of at least 3,000 short-range weapons.”

Both reports compel – each in their own way – the Obama administration to address the issue of tactical nuclear weapons.

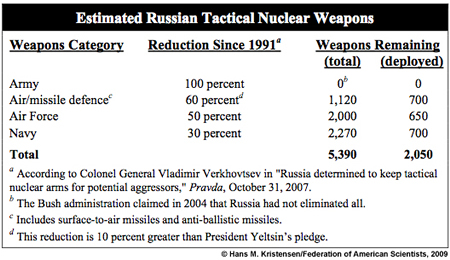

The Russian Inventory

Like the United States, Russia doesn’t say much about the status of its tactical nuclear weapons. The little we have to go by is based on what the Soviet Union used to have and how much Russian officials have said they have cut since then.

Unofficial estimates set the Soviet inventory of tactical nuclear weapons at roughly 15,000 in mid-1991. In response to unilateral cuts announced by the United States in late 1991 and early 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin pledged in 1992 that production of warheads for ground-launched tactical missiles, artillery shells, and mines had stopped and that all such warheads would be eliminated. He also pledged that Russia would dispose of half of all airborne and surface-to-air warheads, as well as one-third of all naval warheads.

In 2004, the Russian Foreign Ministry stated that “more than 50 percent” of these warhead types have been “liquidated.” And in September 2007, Defense Ministry official Colonel-General Vladimir Verkhovtsev gave a status report of these reductions that appeared to go beyond President Yeltsin’s pledge.

Based on this, Robert Norris and I make the following cautious estimate (to be published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in late April) of the current Russian inventory of tactical nuclear weapons:

|

| Estimate from forthcoming Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. |

.

Based on the number of available nuclear-capable delivery platforms, we estimate that nearly two-thirds of these warheads are in reserve or awaiting dismantlement. The remaining approximately 2,080 warheads are operational for delivery by anti-ballistic missiles, air-defence missiles, tactical aircraft, and naval cruise missiles, depth bombs, and torpedoes. The Navy’s tactical nuclear weapons are not deployed at sea under normal circumstances but stored on land.

The Other Nuclear Powers

The United States retains a small inventory of perhaps 500 active tactical nuclear weapons. This includes an estimated 400 bombs (including 200 in Europe) and 100 Tomahawk cruise missiles (all on land). Others, perhaps 700, are in inactive storage.

France also has 60 tactical-range cruise missiles, including some on its aircraft carrier, although it calls them strategic weapons.

The United Kingdom has completely eliminated its tactical nuclear weapons, although it said until a couple of years ago that some of its strategic Trident missiles had a “sub-strategic” mission.

Information about possible Chinese tactical nuclear weapons is vague and contradictory, but might include some gravity bombs.

India, Pakistan, and Israel have some nuclear weapons that could be considered tactical (gravity bombs for fighter-bombers and, in the case of India and Pakistan, short-range ballistic missiles), but all are normally considered strategic.

| Russian Nuclear-Capable Cruise Missile Launch |

|

| A nuclear-capable SS-N-19 Shipwreck cruise missile is launched from a Kirov-class nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser. The ship is equipped with 20 launchers for the SS-N-19 missile, which can carry a 500-kiloton warhead. Other tactical nuclear weapon systems include the SS-N-16 anti-submarine rocket, and the SA-N-6 anti-air missile. |

.

Implications and Issues

Whether Vice Admiral Burtsev’s statement is more than boasting remains to be seen, but it is a timely reminder to the Obama administration of the need to develop a plan for how to tackle the tactical nuclear weapons.

Russia’s nuclear posture is now approaching a situation where there are more tactical nuclear weapons in the inventory than strategic weapons. And NATO’s remnant of the Cold War tactical nuclear posture in Europe seems stuck in the mud of nuclear dogma and bureaucratic inaction.

None of these tactical nuclear weapons are limited or monitored by any arms control agreements, and – for all the worries about terrorists stealing nuclear weapons – are the most easy to run away with.

In April, NATO is widely expected to kick off a (long-overdue) review of its Strategic Concept from 1999. It would be a mistake to leave the initiative on what to do with the tactical nuclear weapons to the NATO bureaucrats. The vision must come from the top and President Obama needs to articulate what it is soon.

U.S. Strategic Submarine Patrols Continue at Near Cold War Tempo

|

| U.S. ballistic missile submarines conducted 31 nuclear deterrent patrols in 2008 at an operational tempo comparable to that of the Cold War. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [updated]

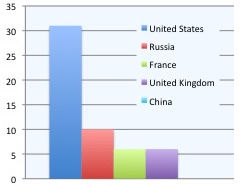

The U.S. fleet of 14 nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines conducted 31 nuclear deterrent patrols in 2008 at an operational tempo comparable to during the Cold War.

The new patrol information, which was obtained from the U.S. Navy under the Freedom of Information Act, coincides with the completion on February 11, 2009, of the 1,000th deterrent patrol by an Ohio-class submarine since 1982.

The information shows that the United States conducts more nuclear deterrent patrols each year than Russia, France, United Kingdom and China combined.

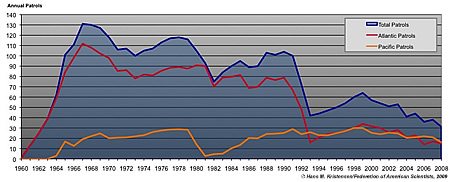

Patrols by the Number

The 31 patrols conducted in 2008 top a 48-year history of continuous deterrent patrols. Since the USS George Washington (SSBN-598) departed Charleston, S.C., on the first nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) patrol on November 15, 1960, 59 SSBNs have conducted 3,814 patrols through 2008 (see Figure 1).

.

The annual number of patrols has fluctuated considerably over the years, peaking at 131 patrols in 1967. Declines occurred mainly due to retirement of SSBNs rather than changes in the mission. The retirement of the early classes of SSBNs in 1979-1981 almost eliminated patrols in the Pacific, but the new Ohio-class gradually rebuilt the posture. The stand-down of Poseidon SSBNs in October 1991 and the retirement of all non-Ohio-class SSBNs by 1993 reduced Atlantic patrols by nearly 60 percent. The patrols increased again in the second half of the 1990s and more Ohio-class SSBNs were added to the fleet, but started dropping from 2000 as four Ohio-class SSBNs were withdrawn from nuclear missions and four others underwent lengthy backfits from the Trident I C4 to the Trident II D5 Trident missile.

|

Figure 2: |

|

|

The United States conducts more SSBN patrols than all other nuclear powers combined. China’s SSBNs have yet to conduct a deterrent patrol. |

During the Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union, the vast majority of patrols were done in the Atlantic Ocean. Since the early 1990s, patrols in the Atlantic have plummeted and the SSBN force been concentrated on the west coast. The majority of U.S. SSBN patrols today occur in the Pacific.

The current number of patrols is significantly greater than the patrol levels of other countries with sea-based nuclear weapon systems. In fact, the U.S. navy conducted three times the number of SSBN patrols that the Russian navy did in 2008, and more patrols than Russia, France, Britain and China combined (see figure 2).

High Operational Tempo

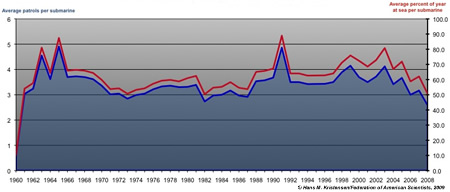

Although the total annual number of SSBN patrols has decreased significantly since the end of the Cold War, the operational tempo of each submarine has not. Each Ohio-class SSBNs today conducts about the same number of patrols per year as during the Cold War, but the duration of each patrol has increased, with each submarine spending approximately 50-60 percent of its time on patrol (see Figure 3).

.

The high operational tempo is made possibly by each SSBN having two crews, Blue and Gold. Each time a submarine returns from a patrol, the other crew takes over, spends a few weeks repairing and replenishing the boat, and takes the SSBN out for its next patrol.

The data also reveals a couple of interesting spikes of increased patrols in 1963/1965 and 1991. The reasons for this increased activity is not known but the periods coincide with the Cuban missile crisis and the failed coup attempt in the final days of the Soviet Union in 1991.

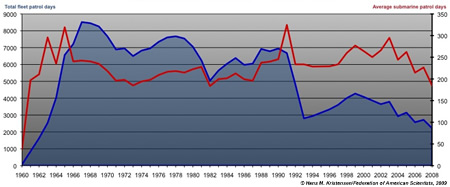

Another way to examine the data is to see how may patrol days each submarine and the fleet accumulate each year. During the Cold War the larger submarine fleet averaged approximately 6,000 patrol days each year, with a peak of 8,515 patrol days in 1967. That performance declined to an average of 3,400 days in the post-Cold War era as the size of the SSBN fleet was reduced. With the removal of four SSBNs from nuclear operations and four others undergoing lengthy missile backfits, the fleet’s total patrol days has now dropped to a little over 2,200 (see figure 4).

.

Yet total patrol day numbers can be deceiving because they can obscure how each submarine is doing. Because the Ohio-class SSBN design was optimized for lengthy deterrent patrols, the average number of days each submarine spends on patrol has been higher in the post-Cold War period than during the Cold War itself. Patrols can be shortened by technical problems, but many Ohio-class submarines today stay on patrol for more than 80 days. Last year, the USS Maine (SSBN-741) conducted a 98-day patrol in the Pacific.

What is a Deterrent Patrol?

An SSBN deterrent patrol is an extended operational deployment during part of which the submarine covers its assigned target package in support of the strategic war plan. Each Ohio-class patrol typically lasts 60-90 days, but one submarine in late 2008 conducted an extended patrol of 98 day and patrols have occasionally exceeded 100 days. Occasionally a patrol is cut short by technical problems, in which case another SSBN can be deployed on short notice. As a result, patrols today in average last about 72 days.

Being on patrol does not mean the submarine is continuously submerged on-station and holding targets at risk. In fact, when the submarine is not on Hard Alert holding targets at risk in Russia, China, or regional states, much of the patrol time is spent on cruising between homeport, patrol areas, exercising with other naval forces, undergoing inspections and certifications, performing Weapon System Readiness Tests (WSRTs), conducting retargeting exercises, and Command and Control exercises.

Another activity involves so-called SCOOP exercises (SSBN Continuity of Operations Program) where the SSBN will practice replenishment or refit in forward ports in case the homeport is annihilated in wartime. In the Pacific, the SCOOP ports include Pearl Harbor, Hawaii (see Figure 5), Guam, Seaward, Alaska, Astoria, Oregon, and San Diego, California. In the Atlantic they include Port Canaveral and Mayport, Florida, Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, and Halifax, Canada. The SSBN may even return to its homeport and redeploy a day or two later on the same patrol.

|

Figure 5: |

|

| USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN-730) loading fresh fruit in Pearl Harbor during a SCOOP visit to Hawaii in March 2008 on its first patrol after a four-year overhaul where it was refueled and modernized to carry the Trident II D5 ballistic missile. |

.

Although patrols normally end at the base where they started, this is not always the case. An SSBN that departs Naval Submarine Base Bangor, Washington, might go on-station for several weeks in alert operational areas, conduct various training and exercises, and then arrive at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. After a brief port visit and replenishment the submarine typically resumes its patrol and eventually returns to Bangor. But sometimes the patrol will end in Hawaii, a new crew be flown in to replace the old, and the submarine undergo refit at the forward location as part of a SCOOP exercise. The SSBN then departs Hawaii on a new patrol, goes on-station in alert operational areas, conducts more exercises and inspections, and eventually returns to Bangor where the new patrol ends.

This type of broken up patrol where the submarine is allowed to do more than on-station operations is sometimes described as “modified alert” and said to be different from the Cold War. But SSBNs have never been on-station all the time, with most deployed submarines being in transit between on-station alert areas and other non-alert operations. In fact, “modified alert” patrols date back to the early 1970s.

Of the 14 SSBNs currently in the fleet, two are normally in overhaul at any given time. Of the remaining operational 12 submarines, 8-9 are deployed on patrol at any given time. Four of these (two in each ocean) are on “Hard Alert” while the 4-5 non-alert SSBNs can be brought to alert level within a relatively short time if necessary. One to three SSBNs are in refit at the home base in preparation for their next patrol.

The SSBNs on Hard Alert continuously hold at risk facilities in Russia, China and regional states with an estimated 384 nuclear warheads on 96 Trident II D5 missiles that can be launched within “a few minutes” after receiving the launch order. The targets in the “target packages” are selected based on the taskings of the strategic war plan, known today as Operations Plan (OPLAN) 8010.

What is the Mission?

But why, nearly two decades after the Cold War ended, are 28 crews ordered to sail 14 SSBNs with more than 1,000 nuclear warheads on 30-plus patrols each year at an operational tempo comparable to that of the Cold War?

The official line is, as stated last month by Secretary of the Navy Donald Winter during the celebration of the 1,000th Ohio-class deterrent patrol, that “the ability of our Trident fleet to [be ready to launch its missiles] 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, has promoted the interests of peace and freedom around the world….Since the beginning of the nuclear age, the world has seen a drastic reduction in wartime deaths.”

|

Figure 6: |

|

|

STRATCOM commander General Kevin Chilton (left) and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Gary Roughead. General Chilton says SSBNs deter not only nuclear conflict but “conflict in general” and are “as equally important today, as they ever were during the height of the Cold War.” |

The warfighters add more nuances, including Commander Jeff Grimes of the Trident submarine USS Maryland (SSBN-738) who at the start of a recent deterrent patrol explained it to Navy Times: “There are nuclear weapons in the world today. Many nations have them. Proliferation is possible in the growing technologies societies have. The power of the deterrent is the knowledge that the capability exists in the hands of controlled people. So on a global scale, deterrence is showing how it’s working every day. We haven’t had a global, world war, in a long time,” he said. “Intelligence is different, the threats are different, so we do adjust the planning and contingencies for strategic operations continually to face the threats that may or may not be seen….We’re there on the front line, ready to go,” Grimes declared.

STRATCOM commander General Kevin Chilton, who in a war would advise the president on which nuclear strike options to use, said recently that although some people thought the Trident mission would end with the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, the SSBNs “are as equally important today, as they ever were during the height of the Cold War….The application of deterrence can actually be more complicated in the 21st century, but some fundamentals don’t change,” he said and added: “And it is not just to deter nuclear conflict. These forces have served to deter conflict in general, writ large, since they’ve been fielded.”

These are strong and diverse claims that are also made in some of the command histories that each SSBN produces. Some of them state that the mission is to “maintain world peace,” which has certainly not been the case in the post-Cold War era. Others describe the mission as “providing strategic deterrence to prevent nuclear war” (my emphasis), which sounds more credible. But even in that case, can we really tell whether it is the SSBNs that prevent nuclear war and not the ICBMs or bombers?

The enormous differences between maintaining world peace, preventing wars, and preventing nuclear war demand that officials articulate the SSBN mission much more clearly. To that end, it would be good to hear why it takes 12 operational SSBNs with more than 1,100 nuclear warheads on 30-plus patrols per year to deter nuclear attack against the United States, but only three operational SSBNs with less than 160 warheads on six patrols per year to safeguard the United Kingdom.

|

Figure 7: |

|

| USS Maryland (SSBN-738) departs Kings Bay on February 15, 2009, for its 53rd deterrent patrol in the Atlantic Ocean to prevent nuclear war, prevent world war, deter conflict, maintain world peace, promote the interests of peace of freedom, deter proliferators, in a mission that remains“equally important…as during the height of the Cold War,” depending on who is describing it. |

.

Last year Russia’s SSBNs returned to sea at a level not seen in a decade and it plans to build eight new Borey-class SSBNs with new multi-warhead missiles. France is completing its fourth Triomphant-class SSBNs also with a new multi-warhead missile, and Britain has announced plans to build four new SSBNs. China is building 3-5 new Jin-class SSBNs with 8000-kilometer missiles, and India is said to be working on an SSBN as well. The U.S. Navy has also begun design work on its next ballistic missile submarine to replace the Ohio-class.

In short, the nuclear powers seem to be recommitting themselves to an era of deploying large numbers of nuclear weapons in the oceans. Most people tend to view sea-based nuclear weapons as the most legitimate leg of the Triad. Yet of all strategic nuclear weapons, sea-based ballistic missiles are the most difficult to track, the most problematic to communicate with in a crisis, the hardest to verify in an arms control agreement, and the only ones that can sneak up on an adversary in a surprise attack.

If the Obama administration wants to decisively move the world toward “dramatic reductions” and ultimately the elimination of nuclear weapons, then it must seek answers to these issues. In the short term, it needs to ask whether the Cold War operational tempo of U.S. SSBNs is counterproductive by sending a signal to other nuclear weapon states that triggers modernization of their forces and makes reductions harder to achieve than otherwise. In other words, what is the net impact of the SSBN patrols on U.S. national security objectives in an era of pursuing nuclear disarmament?

Addition Resources: Russian Sub Patrols | Chinese Sub Patrols

_____________________________________________________________

India’s Nuclear Forces 2008

|

| Mystery missile: widely reported as a future sea-launched ballistic missile, is the Shourya launch in November 2008 (right) a land-based mobile missile (left), a silo-based missile, or a hybrid? Images: DRDO |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A decade after India officially crossed the nuclear threshold and announced its intention to develop a Triad of nuclear forces based on land-, air-, and sea-based weapon systems, its operational force primarily consists of gravity bombs delivered by fighter jets. Short of the short-range Prithvi, longer-range Agni ballistic missiles have been hampered by technical problems limiting their full operational status [Update Feb. 2, 2009: “Defense sources” quoted by Times of India appear to confirm that the Agni missiles are not yet fully operational]. A true sea-based deterrent capability is still many years away.

Despite these constraints, indications are that India’s nuclear capabilities may evolve significantly in the next decade as Agni II and Agni III become operational, the long-delayed ATV nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine is delivered, and warhead production continues for these and other new systems.

Our latest estimate of India’s nuclear forces is available from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

New Chinese SSBN Deploys to Hainan Island

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Chinese navy has deployed a Jin-class (Type 094) ballistic missile submarine to a new base near Yulin on Hainan Island on the South China Sea, according to a satellite image obtained by FAS. The image shows the submarine moored at a pier close to a large sea-entrance to an underground facility.

Also visible is a unique newly constructed pier that appears to be a demagnetization facility for submarines.

A dozen tunnels to underground facilities are visible throughout the base compound.

The satellite image, which has also been described in Jane’s Defense Weekly, was taken by the QuickBird satellite on February 27, 2008, and purchased by FAS from DigitalGlobe.

The Arrival of the Jin-Class Submarine

The dimensions of the submarine in the satellite image are similar to the Jin-class SSBN I spotted at Xiaopingdao Submarine Base in July 2007 and the two Jin-class SSBNs I detected at the Bohai shipyard in October 2007.

China is believed to have launched two Jin-class SSBNs with a third possibly under construction. The U.S. Intelligence community estimates that China might possibly build five SSBNs if it wants to have a near-continuous deterrent at sea. Of course, it is not known whether China plans to operate its SSBNs that way. See Figure 1 for the location of the submarine.

.

Missile loadout of the SSBN will probably take place at pierside at the main pier to the left of the narrow triple-pier where the submarine is seen, unless the underground facility is large enough to permit such operations out of satellite view. Not yet visible at the base is a dry dock large enough to accommodate an SSBN; the Northern Fleet submarine base at Jianggezhuang has a dry dock.

New Demagnetization Facility

One of the most interesting new additions to the base is what appears to be a submarine demagnetization facility (see Figure 2). Located in the southern part of the base and connected by pier to a facility on a small island, the demagnetization facility closely resembles such facilities at U.S. SSBN bases. Demagnetization is conducted before deployment to remove residual magnetic fields in the metal of the submarine to make it harder to detect by other submarines and surface ships. There is no demagnetization facility at the Jianggezhuang base, so this appears to be a new capability for China.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Since 2005, what appears to be a submarine demagnetization facility has been added to the base. Click on image for larger photo. |

.

Underground Facilities

The base has extensive underground facilities. The most obvious is a large portal over a sea-entrance to what is probably an underground facility. The entrance appears to be approximately 3 meters (15 feet) wider than a similar entrance at the Northern Fleet Jianggezhuang Naval Base (see Figure 3 for comparison).

|

Figure 3: |

|

| The submarine cave entrance at Yulin Naval Base (top) is approximately 3 meters wider than the one at Jianggezhuang Naval Base. Click on image for larger photo of the Yulin entrance. Description of the Jianggezhuang facility is available here. |

.

Although the interior of the facility is not known, it probably includes a canal at least the length of one submarine as well as halls for handling or possibly storing equipment as well as rooms for personnel. Directly on the other side of the mountain are several land-entrances that might connect to the central facility as well, although none of this is known for sure. Two of those entrances appear from their shadows to be very tall structures (see Figure 4).

.

Some Implications

The SSBN base on Hainan Island will probably be seen as a reaffirmation of China’s ambitions to develop a sea-based deterrent. To what extent the Chinese navy will be capable of operating the SSBNs in a way that matters strategically is another question. China’s first SSBN, the Xia, was no success and never sailed on a deterrent mission. As a consequence, the Chinese navy has virtually no tactical experience in operating SSBNs at sea. Yet the Jin-class and the demagnetization facility on Hainan Island show they’re trying.

The location of the base is important because the Indian government already has pointed to a future threat from Chinese missile submarines operating in the South China Sea or Indian Ocean. The arrival of the Jin-class in Hainan will probably help sustain India’s own SSBN program. For China to sail an SSBN into the India Ocean and operate it there in a meaningful way, however, will be very difficult and dangerous in a crisis. Chinese SSBNs are more likely to stay close to home.

The base on Hainan Island is near deep water and some analysts suggest this will support submarine patrols better that operations from the Northern Fleet base at Jianggezhuang. Of course, if the water is so shallow the submarine can’t submerge fully it will limit operations, but deep water is – contrary to popular perception – not necessarily an advantage. Military submarines generally are not designed to dive deeper than 400-600 meters, so great ocean depth may be of little value. The U.S. navy has several decades of experience in trailing Soviet SSBNs in the open oceans; shallow waters are much more challenging. And the South China Sea is a busy area for U.S. attack submarines, which have unconstrained access to the waters off Hainan Island. And I’d be surprised if there were not a U.S. “shadow” following the Jin-class SSBN when it arrived at Hainan Island.

Additional information: Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning | Chinese Submarine Patrols Rebound in 2007, but Remain Limited | A Closer Look at China’s New SSBNs

Congressman Markey on the US-India Nuclear Deal

Last week, Congressman Ed Markey (D-Mass) visited FAS to talk about the India-US deal. Markey, who strongly supports closer ties with India, opposes the nuclear deal because it undermines the Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT). A transcript and video of his comments are on the FAS website.

What I found most interesting about his talk was a graphic showing the growth in U.S.-Indian trade over the past few decades. (Our chart is not a reproduction of the chart used my Mr. Markey but created from the same data.) It goes up…and up and up. It has gone up even during politically difficult times, for example, after the 1974 Indian nuclear test. The Congressman’s point is that, when people argue for the nuclear deal because it will allow a blossoming of trade between the two countries, they miss the point entirely. Trade with India has been growing for years, it continues to grow now, and it will grow in the future whether we have a nuclear deal or not. So the trade benefit is simply not there. But the harm done to the NPT definitely remains.

(more…)