Congressional briefing: Potential of fluvoxamine to counter COVID-19

There has been a surge of public interest in the drug fluvoxamine as a potential treatment for individuals with mild COVID-19, and Congressional offices are receiving many questions about the possibility of using the drug to counter COVID-19 from constituents. This brief outlines what is known to date about fluvoxamine in the context of the coronavirus pandemic in order to help both policymakers and scientists discuss this issue with those in their communities.

Fluvoxamine is a long-used drug that showed promising preliminary results in a small, well-controlled COVID-19 patient study

The generic drug fluvoxamine (also referred to by the brand name Luvox) was first synthesized in 1971, and is used to treat anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Fluvoxamine blocks serotonin reuptake in the brain, but it is chemically unrelated to other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors that are used to treat anxiety or depression, like fluoxetine (Prozac) or sertraline (Zoloft). Studies have demonstrated that fluvoxamine also binds a protein in mammalian cells called the sigma-1 receptor. One of this receptor’s functions is to regulate cytokine production; cytokines cause inflammation. When fluvoxamine has been used in the laboratory, it results in a dampened inflammatory response in human cells in the test tube, and protects mice from lethal septic shock, which is an out-of-control immune response to infection, causing massive inflammation that can impede blood flow to major organs, and result in organ failure. Notably, retrospective analyses have indicated that COVID-19 patients given antipsychotic drugs that target the sigma-1 receptor were less likely to require mechanical ventilation than COVID-19 patients given other antipsychotic drugs, and some drugs that bind the sigma-1 receptor also have antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in the petri dish.

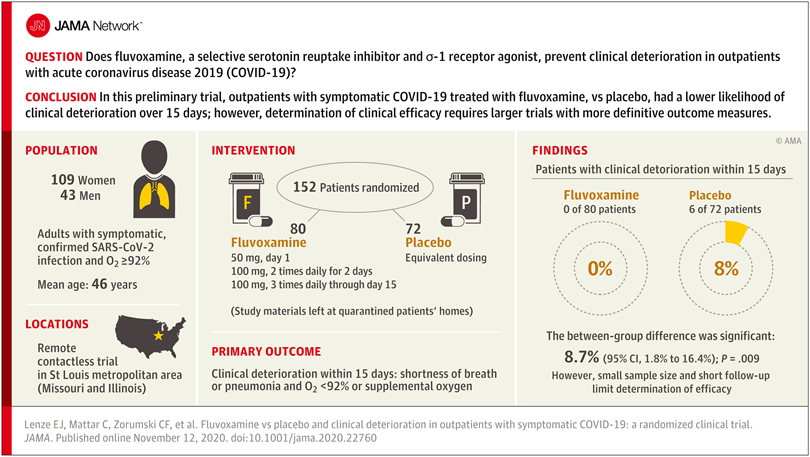

Researchers reasoned that fluvoxamine may be able to stave off the “cytokine storm” that can lead to the out-of-control inflammatory response that appears to cause severe respiratory and blood-clotting issues for some people infected with the coronavirus, and tested the drug in a pilot study to gauge whether it has potential as a treatment for COVID-19. The study was a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of 152 non-hospitalized adults with mild COVID-19. Treatment of symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19 patients started within 7 days of their diagnosis. None of the 80 patients treated with fluvoxamine experienced clinical deterioration, compared to 6 of 72 patients treated with placebo who experienced both “1) shortness of breath or hospitalization for shortness of breath or pneumonia and 2) oxygen saturation less than 92%.” While this amounted to a statistically significant difference, the study serves as only preliminary evidence for the efficacy of fluvoxamine as a therapy to counter COVID-19, and a much larger clinical trial has been initiated to pursue conclusive results.

Further study of treating many more COVID-19 patients with fluvoxamine is required before the drug should be used outside of clinical trials as a therapy to counter COVID-19

While the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized design of the clinical trial does minimize bias and provide the opportunity to identify a causal relationship between treatment and patient outcome, larger randomized trials with more definitive metrics in place for assessing patients’ health status are necessary in order to reach a conclusion about whether fluvoxamine should be used to treat patients with COVID-19 outside of clinical trials. The findings of this single, small study are a launching point for larger clinical trials, and “should not be used as the basis for current treatment decisions.”

The limitations of the study include the small number of COVID-19 patients involved and the low number of patients in the placebo group whose conditions worsened – only six. And while fluvoxamine is safe, easily accessible, administered orally, and inexpensive, it may interact with other drugs, and does have some side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, increased sweating, dizziness, drowsiness, insomnia, or dry mouth.

The researchers who performed this pilot study are currently conducting a larger clinical trial to conclusively determine whether fluvoxamine is an advisable treatment for mild COVID-19. The trial is expected to be watched closely since the identification of drugs – in addition to the monoclonal antibody treatments developed by Regeneron and Eli Lilly – that could be used to reduce the likelihood of progression from mild to more severe COVID-19 would greatly improve health outcomes for people infected by the coronavirus, as well as reduce the burden on the US healthcare system.

–

This briefing document was prepared by the Federation of American Scientists along with Professor Alban Gaultier at the University of Virginia and Professor David Boulware at the University of Minnesota.

By advocating for the integration of technology-focused green jobs within federal initiatives, there is an opportunity to broaden the talent pool and harness the potential of emerging technologies to tackle pressing environmental issues.

“We really wanted a range of perspectives – specifically from voices that have been traditionally left out of the conversation”

Understanding the implications of climate change in agriculture and forestry is crucial for our nation to forge ahead with effective strategies and outcomes.

In the quest for sustainable energy and materials, biomass emerges as a key player, bridging the gap between the energy sector and the burgeoning U.S. and regional bioeconomies.