New START Data Shows US Implementation, Questions About Bomber Force

By Hans M. Kristensen

While defense hawks try to block funding for implementing the US-Russian New START treaty, the US military is making rapid process toward meeting the treaty limits by February 2018.

The latest full declassified aggregate data for the US force structure under New START shows that both the ICBMs and bombers appear to have reached the force level planned and more than two-thirds of the SSBN fleet has been converted as well.

But the implementation also raises questions about what the plan is for the future bomber force structure. Depending on how many new B-21 bombers the Air Force will deploy how soon and how many will be nuclear-capable, the Air Force might have to withdraw the B-52 from the nuclear mission by the early 2030s.

This also raises questions about the need to deploy the new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (RLSO) on the B-52 bombers. The new B-21 is intended to take over the nuclear air-launched cruise missile mission. The B-2 appears to have been eliminated as a future LRSO platform.

The ICBM Force

The Minuteman III ICBM force is listed with 405 deployed missiles, a reduction of 8 since September 2016. Since this count was reported, the Air Force has removed the last 5 ICBMs from their silos, leaving 400 deployed ICBMs, the goal identified in the New START Implementation report.

A Minuteman III ICBM is removed from its silo at Malmstrom AFB on June 2, 2017, as part of US implementation of the New START treaty.

The ICBM reduction is spread evenly across the three missile wings (133 ICBMs per wing), but other detailed New START data obtained from State Department shows that Malmstrom AFB was the first of the three wings to reach the 133 number.

Although the number of deployed ICBMs has been reduced, the total number of deployed and non-deployed ICBMs has not gone down but remains at 454 as in September 2016. The reason is that the reduction of 50 deployed ICBMs since 2011 requires the 50 empty silos to be kept “warm” and ready for redeployments if necessary. There is no strategic need to do so.

All deployed Minuteman III ICBMs have been “de-MIRVed” and currently carry one warhead each. Yet more than half of the force (those with the W78/Mk12A reentry vehicle) can still carry up to three warheads; the additional warheads are in storage. The remaining W87/Mk21-equipped ICBMs can only carry one warhead each. However, all of the next-generation ICBMs (currently known as Ground Based Strategic Deterrent, GBSD) will be MIRVable.

The SSBN Force

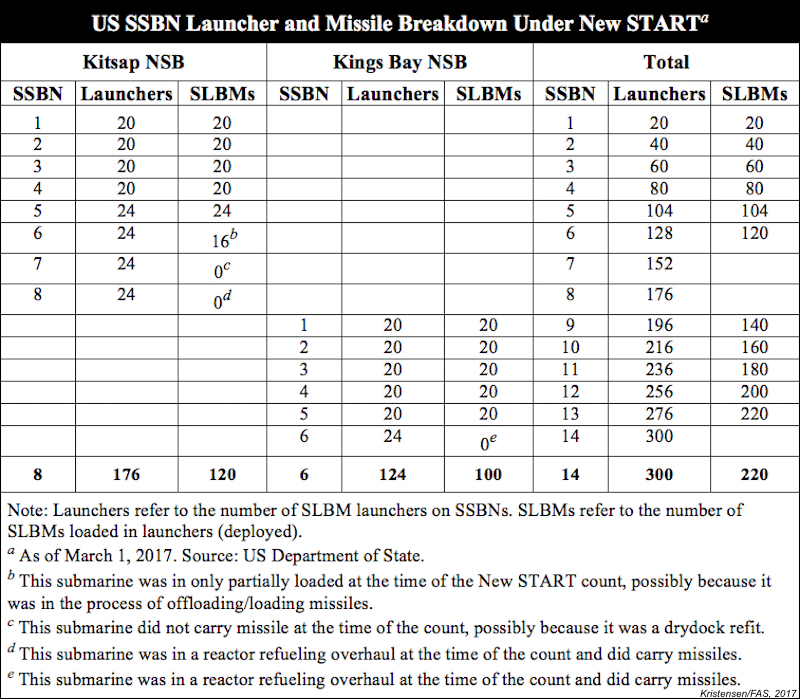

The New START data shows that US SSBNs carried a total of 220 SLBMs at the time of the count. That’s 11 missiles more than the previous count in September 2016. A total of 80 launchers were empty (three SSBNs in drydock and one in missile handling) for a total of 300 missile launch tubes.

Nine of the 14 SSBNs appear to have been converted to 20 missile launchers, a reduction of 4 missile launchers per boat to meet the New START overall limit of 700 deployed launchers. As of March 2017, the navy still had to inactivate a total of 20 launch tubes on five SSBNs to reach the goal of 280 deployed and non-deployed SLBM launchers by February 2018. Of those, no more than 240 will be deployed at any time.

The USS Alaska (SSBN-732) that returned to Kings Bay in mid-June following its 100th deterrent patrol since 1986, probably carried 20 Trident II SLBMs loaded with 88 nuclear W76-1 and W88 warheads.

Additional information obtained from State Department shows where the changes have been made (see table below). The Atlantic fleet has almost completed the conversion to 20 launchers per SSBN (one sub in refueling overhaul is probably being converted), while the Pacific fleet still has three SSBNs with 24 missiles, but two of them were empty at the time of the count (one of them in refueling overhaul) and a third was only partially loaded (probably undergoing missile handling).

The full declassified aggregate data also shows that there were a total of 958 warheads onboard deployed SLBMs as of March 2017, or nearly two-thirds of the total warhead number permitted by New START by February 2018. The United States does not need to make additional reductions in deployed warheads but could in fact increase the number of warheads deployed on SSBNs by another 139 warheads if it decided to do so.

The Heavy Bomber Force

The reduction of nuclear bombers appears to be complete. The Air Force has not yet declared so in public, but the data shows the number of deployed and non-deployed nuclear bombers are down to 66 – the same number required by the New START Implementation report. That is a reduction of 45 bombers compared with the inventory of 111 nuclear-capable bombers declared back in September 2011 (another 39 retired bombers were also declared as nuclear at the time but did not have an actual nuclear mission).

B-1, B-2 and B-52 bombers at RAF Fairfield in England on June 12, 2017. B-1 is equipped with conventional JASSM-ER. The B-2 and B-52 are nuclear-capable and part of the 66 nuclear bomber force planned under the New START treaty.

At 48, the number of deployed nuclear bombers is now 12 aircraft below the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” the Pentagon set in 2010 as the New START force level. That development is despite the B-52s having lost the nuclear gravity bomb mission and is now only delivering ALCMs; only the B-2 today has a strategic gravity bomb mission. The willingness to drop below the 60 indicates that there is excess capacity in the nuclear bomber force.

Moreover, with a New START force level of 66 deployed and non-deployed nuclear bombers (20 B-2s and 46 B-52s), an important question is how many of the new B-21 bombers will be nuclear-capable. The Air Force wants “a minimum of 100” B-21s in total and Lt Gen Jack Weinstein, the Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for strategic deterrence and nuclear integration, reportedly told Flight Global that the entire fleet of B-21s will be dual-capable.

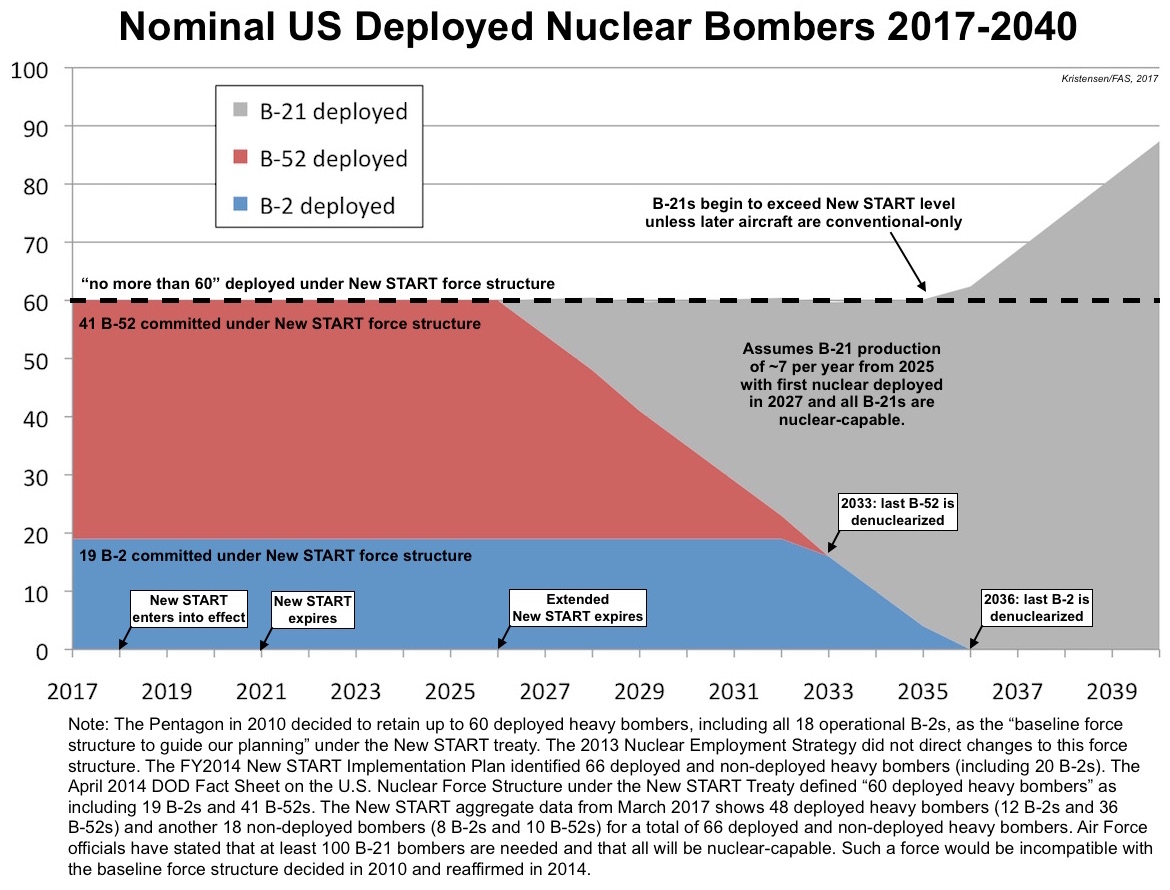

The Air Force wants more than 100 B-21 bombers and officials say all will be nuclear-capable. That would violate the force level of “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” planned under New START.

If that were the case, then it would raise questions about US long-term nuclear forces plans, challenge nuclear arms control, and potentially influence strategic stability. Assuming delivery of about seven B-21s per year starting in 2025 and the first nuclear-capable aircraft two years later, the US would by 2028 begin to exceed the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” pledged in 2010 and reaffirmed in April 2014, unless it begins to denuclearize B-52 and B-2 bombers as the B-21 enters the force. Although that would be two years after a possible extended treaty had expired in 2026 leaving the United States free of legal constraints, the Pentagon currently uses the New START force level as long-term guidance for the force structure. So a decision to go beyond “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” would be a significant change.

To avoid exceeding the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” force level, it would be necessary to begin reducing the number of B-52s in the nuclear mission pretty much as soon as the B-21 begins to enter the force. By the mid-2030s, all the B-52s would have to be out of the nuclear mission, and the B-2 would have to begin withdrawing from the nuclear mission as well. By 2037, there would only be room for B-21s in the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” force level. Any B-21 produced after that year would have to be conventional-only (see graph below). A slower B-21 production would obviously affect this projection.

How the nuclear bomber force structure evolves also has implications for development and deployment of the new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (LRSO). The Air Force has previously stated that the LRSO would be made compatible with all three nuclear bombers: B-2, B-21, and B-52. In testimony before the U.S. Congress in July 2016, Air Force Global Strike Command listed all three bombers as part of the LRSO program, but in its June 2017 testimony the command only said the LRSO “will be compatible with B-52 and B-21 platforms.” Apparently, the B-2 has been removed from the LRSO program. [Update 7/26/2017: Although AFGSC chief Gen Rand omitted the B-2 from his 2017 congressional testimonies, AFGSC PA told me the “LRSO will be compatible with B-2, B-52, and B-21″ but also reminded that the Trump administration’s NPR “will guide modernization efforts, including the future of our bombers.”]

But the B-52 is still intended to be made compatible with the LRSO. By the time the new missile becomes operation in 2030, however, half of the B-52s that are currently nuclear-capable might already have been denuclearized to make room for the B-21 under the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” force level (see above). The remaining nuclear B-52s would be gone from the force only a few years later, which appears to make the fielding of the LRSO on the B-52 a waste of money and effort.

The Air Force should clarify its plans for the bomber force, whether it intends to keep the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” force structure, how many B-21s will be nuclear-capable, and whether the LRSO needs to be made compatible with the B-52 at all.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.

While advanced Chinese language proficiency and cultural familiarity remain irreplaceable skills, they are neither necessary nor sufficient for successful open-source analysis on China’s nuclear forces.