Russian SSBN Fleet: Modernizing But Not Sailing Much

The second Borei-class SSBN (Alexander Nevsky) is fitting out at the Severodvinsk Naval Shipyard in northern Russia. Six of its 16 missile tubes are open on this August 2011 satellite image by DigitalGlobe/GoogleEarth.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Russian ballistic missile submarine fleet is being modernized but conducting so few deterrent patrols that each submarine crew cannot be certain to get out of port even once a year.

During 2012, according to data obtained from U.S. Naval Intelligence under the Freedom of Information Act, the entire Russian fleet of nine ballistic missile submarines only sailed on five deterrent patrols.

The patrol level is barely enough to maintain one missile submarine on patrol at any given time.

The ballistic missile submarine force is in the middle of an important modernization. Over the next decade or so, all remaining Soviet-era ballistic missile submarines and their two types of sea-launched ballistic missiles will be replaced with a new submarine armed with a new missile (see also our latest Nuclear Notebook on Russian nuclear forces).

The new fleet will carry more nuclear warheads than the one it replaces, however, because the Russian military is trying to maintain parity with the larger U.S. nuclear arsenal.

Sluggish Deterrent Patrols

The operational tempo of the Russian SSBN fleet – measured in the number of deterrent patrol conducted each year – has declined significantly – actually plummeted – since the end of the Cold War.

At their peak in 1984 – the year after the Russian military became convinced that the NATO exercise Able Archer was in fact disguised preparations for a nuclear first strike against the Soviet Union, Russian SSBNs carried out 102 patrols. Under Mikhail Gorbachev, operations quickly declined in the second half of the 1980s. But even as the Warsaw Pact collapsed and the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the fleet was able to muster a slight comeback in 1990.

As the Cold War officially ended in 1990, the Soviet Union dissolved and Russia descended into financial recession, the SSBN force increasingly stayed in port until in 2002, when no deterrent patrols were conducted all.

Since then, the performance has been a mixed bag. After a slight whiff of new life with 10 patrols in 2008 (up from 3 in 2007), the number of SSBN patrols has declined again to around five in 2012.

The recent decline contrasts with the Russian Navy’s declaration last year that it would resume continuous deterrent patrols from mid-2012. Assuming the five patrols occurred throughout the year and not just in the last six months, the fleet would have had a hard time maintaining a continuous at-sea presence with only five patrols. Theoretically, it could be done if each patrol lasted an average of 73 days. That is how long a U.S. SSBN deploys on a good day. But Russian SSBNs are thought to do shorter patrols, probably 40-60 days each, in which case most of the five patrols would have had to occur between July and December to maintain continuous patrol from mid-2012.

Even if the navy were able to squeeze a more or less continuous at-sea presence out of the five patrols, it would at best have consisted of a single SSBN – not much for a fleet of nine submarines or demonstrating a convincing secure retaliatory capability.

Perhaps more significantly, the five deterrent patrols conducted in 2012 are not enough for each SSBN in the fleet to be able to conduct even one patrol a year. The five patrols by nine SSBNs indicate that only five or less submarines are active. That means that submarine crews do not get much hands-on training in how to operate the SSBNs so they actually have a chance to survive and provide a secure retaliatory strike capability in a crisis. Crews probably compensate for this by practicing alert operations at pier-side at their bases.

Unlike U.S. SSBNs, which can patrol essentially with impunity in the open oceans, Russian deterrent patrols are thought to take place in “strategic bastions” relatively close to Russia where the SSBNs can be protected by the Russian navy against the U.S. and British attack submarines that probably occasionally monitor their potential targets.

The Russian navy remembers all too well the 1980s when the aggressive U.S. Maritime Strategy envisioned using attack submarines to hunt down and destroy Soviet SSBNs early on in a conflict, a highly controversial strategy [see here and here] that could likely have triggered escalation to strategic nuclear war. Hunting Russian SSBNs is no longer a primary mission for U.S. attack submarines, but it is probably still part of the mission package and one that Russian planners cannot afford to ignore. As a result, Russian SSBNs probably continue to patrol in the areas used in the late-1980s and early-1990s (see map) to provide maximum protection.

Force Structure

Russia currently operates 10 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), of which three Delta IIIs based in the Pacific are outdated and six Delta IVs based in the Barents Sea have recently been refurbished to serve for another decade or so. The 10th SSBN added in January 2013 is the first of a new type of Borei-class SSBNs that are scheduled to replace all Deltas by the mid/late-2020s.

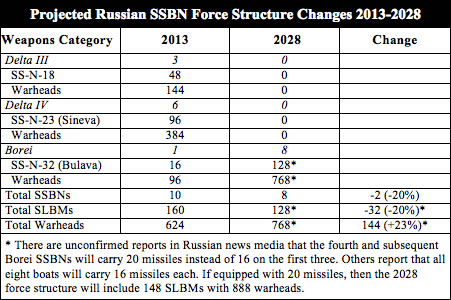

The first Borei-class (Project 955) SSBN, Yuri Dolgoruki, entered service after more than 15 years of design and construction, marking the first time in 25 years that the Russian Navy had commissioned a new SSBN. A second Borei has been launched and a third is under construction. Russia has announced plans to build a total of eight Boreis. Each Borei is equipped with 16 SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBMs, a missile that Russia has declared can carry up to six warheads.

The fourth and subsequent Borei-class SSBNs will be of an improved design, known as Borei-II or Project 955A). Russian news media is full of rumors that the improved Boreis will be equipped with 20 SLBMs instead of 16 on each of the first three boats. Some Russian officials dispute that, saying all Boreis will be equipped with 16 missiles.

This force structure plan has implications for Russia’s nuclear posture and strategic priorities. The replacement of the Delta SSBNs with eight Borei SSBNs will reduce the size of the Russian SSBN fleet and the number of SLBMs, but result in a 23-percent increase in the number of sea-based warheads because the SS-N-32 carries more warheads than the SS-N-18 and SS-N-23 SLBMs it replaces.

In other words, Russia will be placing more eggs in fewer baskets at sea, which increases the importance of each SSBN – something strategists say is bad for crisis stability.

Conclusions and Implications

The Russian SSBN force is in the middle of a transition from Soviet-era weapons to a smaller but more warhead-heavy fleet of new submarines.

This means that the SSBN fleet will carry a growing portion of Russia’s strategic missile warheads – up from about a third today to nearly half by the mid-2020s.

The trend of increased warhead loading on sea-launched ballistic missiles is similar to the development on land where reduction of the Russian ICBM force will result in a greater portion of the remaining force being equipped with multiple warheads.

This is perhaps the most dominant trend of Russia’s nuclear forces today: fewer launchers but each carrying more warheads. Not that Russia will have more total nuclear warheads than before (their arsenal is declining), but that military planners have fallen for the temptation to place more nuclear eggs in each basket.

They appear to do so to compensate againt the larger U.S. nuclear missile force and its significant reserve of additional warheads. But it would be helpful if the Russian government would declare how many Borei-class SSBNs it plans to build in total and limit the number of missiles on each to 16.

The Russian modernization is motivating Cold Warriors in the U.S. Congress to argue that the United States should not reduce but modernize its nuclear forces. They are wrong for many reasons, not least because the two postures are very different.

The U.S. SSBN fleet is more modern with another 15 service years left in it, and it carries many more missiles that are much more reliable with more warheads. The U.S. could in fact easily reduce its SSBN fleet to ten boats, perhaps fewer.

Moreover, in contrast with U.S. SSBN operations, where each operational submarine conducts an average of 2-3 patrols each year, Russian SSBN crews do not get a lot of operational training with an average of less than one patrol per submarine per year.

Rather than opposing further reductions, U.S. lawmakers should support limitations on the growing asymmetry between U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear forces – an asymmetry that is significantly in the U.S. advantage – to help limit further concentration of nuclear warheads on Russia’s declining numbers of strategic missiles. That would actually help the national security interests of all.

See also: Russian nuclear forces, 2013

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.