The History of U.S. Decision-making on Nuclear Weapons in Japan

Earlier this month, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper said he favored placing conventional intermediate-range missiles in Asia following the demise of the INF treaty. While Secretary Esper did not indicate where the missiles might be deployed, many security experts believe Japan to be the most likely candidate. The tight U.S.-Japan security alliance built from the American Occupation has historically set up Japan as an ideal staging ground for U.S. weapons systems. Though Secretary Esper and most proposals for intermediate-range missiles in Asia refer to conventional weapons, because of their strategic importance, many Japanese are likely to read these proposals as part of a long and politically fractious history of US weapons deployments to Japanese territory that included nuclear weapons.

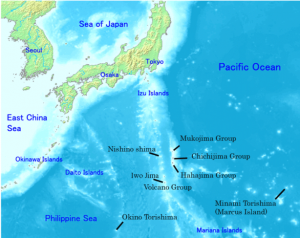

Japan’s strategic location in the Pacific coupled with the heavy American influence on the emerging democracy made it an attractive option to host U.S. nuclear weapons during the Cold War. U.S. control of Japan’s southern island chain presented a strategic opportunity to forward deploy tactical nuclear weapons into an increasingly volatile Pacific region where war planners anticipated their increased military utility as they planned force postures to respond to the aftermath of the Korean War and the Chinese Civil War.

In 1959, Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi first declared that Japan would neither develop nor permit nuclear weapons on its territory. This declaration formed the cornerstone of Prime Minister Eisaku Sato’s 1967 establishment of Japan’s “three non-nuclear principles” which promise not to process, produce, or permit the introduction of nuclear weapons into Japan. The Diet formally adopted these principles through a resolution in 1971, though they are not legally binding. Prime Minister Sato, worried that the three non-nuclear principles were too binding on Japan’s defense posture, supplemented the policy in February 1968 with his “four pillars nuclear policy.” The four pillars were to promote peaceful use of nuclear power, to work toward global nuclear disarmament, to rely on the extended U.S. nuclear deterrent, and to support the three non-nuclear principles.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, U.S. officials often complained that Japan’s “nuclear allergy” imposed constraints on U.S. nuclear force posture. But despite the Japanese government’s public anti-nuclear stance, the nuances of the bilateral security relationship and treaty language emboldened the U.S. to deploy nuclear weapons to Japan in the mid-1950s. The occupation of mainland Japan ended in 1951 but the Treaty of San Francisco allowed the U.S. to maintain its control over Japan’s southern island chains, which include the islands of Okinawa, Iwo Jima, and Chichi Jima. War planners worried that compromised communication systems in a time of crisis would make emergency deployments and transfers of nuclear weapons difficult or impossible, so they sought to establish a forward deployed posture in the Pacific.

The bulk of the nuclear weapons were stored on Okinawa at the Henoko Ordnance Ammunition Depot adjacent from Camp Schwab and the Kadena Ammunition Storage Area at Kadena Air Base, where SAC’s strategic bombers were based. Between 1954 and 1972, the bases on Okinawa hosted 19 different types of nuclear weapons. At the height of the Vietnam War, around 1,200 nuclear weapons were stored on Okinawa alone. A document declassified in 2017 shows that in 1969 Japan officially consented to the U.S. bringing nuclear weapons to Okinawa.

Every American president from 1952 onward remained publicly committed to the reversion of Okinawa, but was privately reluctant to initiate the hand-over. During the 1950s to mid-1960s, the Japanese were largely willing to accept reversion as a distant goal, in part because the U.S.-backed Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) that held power in the post-Occupation era was hesitant to challenge the U.S. on the issue. The Japanese government also recognized the security value of U.S. forces stationed in Okinawa, given Japan’s restraining pacifist constitution. However, in the late-1960s, pressure began to build from the Okinawans and the mainland Japanese establishment to return the island to Japan.

Prime Minister Sato first raised the issue with the U.S. in 1967 during talks with President Johnson. President Johnson responded that because of the 1968 election and the war in Vietnam, the U.S. would be unable to address reversion of Okinawa until 1969 at the earliest. In March of 1969, Henry Kissinger sent President Nixon a memo outlining the Japanese demands for reversion as well as the relevant military and political considerations. While the memo acknowledged that public demand within Japan for reversion was growing politically untenable for Prime Minister Sato, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff were primarily concerned about the effect of reversion on nuclear storage and military activities such as B-52 operations against Vietnam. On nuclear storage, Kissinger wrote, “The loss of Okinawan nuclear storage would degrade nuclear capabilities in the Pacific and reduce our flexibility.”

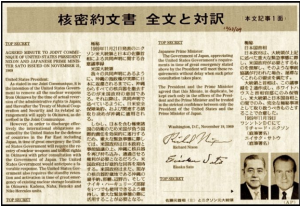

Top secret agreement allowing the U.S. to maintain emergency reactivation of nuclear weapons storage on U.S. bases in Okinawa. (Image courtesy of Union of Concerned Scientists.)

While the Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted the Nixon Administration to push for continued nuclear storage post-reversion, Kissinger wrote that it was unlikely that the Japanese Diet would support it in face of growing public dissatisfaction, even if Prime Minister Sato agreed. Kissinger added that “…in the slim possibility that Japanese agreement to nuclear storage is obtained, we must recognize that the Japanese proponents of this position view this as the opening wedge for an independent Japanese nuclear force.” Kissinger recommended that the U.S. return Okinawa to Japanese control and give up nuclear storage on the island in order to maintain basing rights, emergency nuclear storage rights, and full nuclear transit rights.

Prime Minister Sato and President Nixon agreed to the reversion of Okinawa in 1969. The agreement contained a secret clause permitting the U.S. to reintroduce nuclear weapons to its Okinawa bases in the case of an emergency. Okinawa was officially returned to Japan in 1972 and shortly after all U.S. nuclear warheads were withdrawn.

In 2016, the U.S. government officially declassified the fact that nuclear weapons were deployed to Okinawa before 1972. It also declassified “the fact that prior to the reversion of Okinawa to Japan that the U.S. Government conducted internal discussion, and discussions with Japanese government officials regarding the possible re-introduction of nuclear weapons onto Okinawa in the event of an emergency or crisis situation.”

While military planners believed the forward deployed nuclear weapons on Okinawa were useful in launching potential attacks against China, Russia, or Vietnam, they feared that in the event of nuclear war with either China or Russia, the U.S. bases on Okinawa would be attacked and destroyed early. In order to maintain a viable second salvo in the Pacific, nuclear weapons were also stored on the U.S.-controlled islands of Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima. Iwo Jima became a fallback support station for the Far East Air Force, maintaining an unknown arsenal of atomic bombs that bombers could pick up for a second strike after dropping their first load on China or Russia. Chichi Jima was outfitted with W5 nuclear warheads for Regulus missiles to serve as a reload point for Regulus submarines if U.S. bases in Japan, Pearl Harbor, Guam, and Adak were destroyed in nuclear war.

The U.S. maintained nuclear weapons as well as other military support structures on Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima into the mid-1960s. The Japanese had been pushing for return of Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima, and Okinawa since the mid-1950s and by 1964, U.S. diplomats in Tokyo also began pressuring Washington to return the islands to Japan, believing it vital to maintaining the cooperative and positive relationship the two countries shared. President Johnson, realizing that returning Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima would be a necessary concession in order to delay the return of the more strategically valuable island of Okinawa, reverted control of Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima to Japan in 1968. All nuclear weapons were removed from the islands by the time of their reversion, but the agreement President Johnson and Foreign Minister Takeo Miki signed would allow the U.S. to redeploy nuclear weapons to the islands in an emergency, upon consultation with the Japanese government. The U.S. government has not confirmed the deployment of nuclear weapons to Iwo Jima or Chichi Jima.

In addition to the nuclear weapons stored on Japan’s southern island chains, the U.S. allegedly stored nuclear weapons without the fissile cores on the Japanese mainland at Misawa and Itazuki airbases until 1965, avoiding by mere semantic technicality violation of Japan’s sovereignty and the integrity of Japan’s three non-nuclear principles. Nuclear armed naval ships were also allegedly allowed to transit Japanese waters and dock at mainland ports with tacit Japanese approval into the 1980s under an oral agreement the two countries made when Japan and the U.S. renegotiated the U.S.-Japan mutual security treaty in 1960.

While the U.S. government has never confirmed that U.S. naval ships carrying nuclear weapons visited Japanese ports, there are two instances that support this claim. In 1974, retired Rear Admiral Gene La Rocque who formally commanded a flagship of the Seventh Fleet, testified before Congress that “any ship capable of carrying nuclear weapons carries nuclear weapons. They do not unload them when they go into foreign ports such as Japan or other countries.”

In 1981, Edwin O. Reischauer, former U.S. Ambassador to Tokyo during the 1960s, acknowledged in a newspaper interview that Japan was permitting U.S. naval ships carrying nuclear weapons to transit Japanese ports under the aforementioned oral agreement. According to Reischauer, American warships could bring nuclear weapons into Japanese waters and ports during routine visits but were not allowed to be unloaded or stored in Japan. The agreement allowed the same freedom to U.S. military planes carrying nuclear weapons.

Both disclosures incited protests from the Japanese public, which has adamantly maintained its anti-nuclear posture since U.S. atomic bombs destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. However, the historical record shows that the Japanese executive branch, dominated for decades by conservative LDP politicians, has at times acquiesced to asserted U.S. military necessities when it comes to nuclear weapons.

The coalitional Diet however has been historically reluctant to publicly support such domestically unpopular measures as allowing U.S. nuclear weapons into Japanese territory or developing an independent nuclear force. This reluctance extends to the possible deployment of conventional intermediate-range missiles being discussed among U.S. defense specialists today.

Policymakers and analysts should be aware of the complex history of US weapons deployments to Japan when discussing future deployments. It should be expected that proposed deployments will face similarly strong political reactions from activists, civil society groups, and communities who remember this history first hand.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.