Photo Depicts Potential Nuclear Mission for Pakistan’s JF-17 Aircraft

Due to longstanding government secrecy, analyzing Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program is fraught with uncertainties. While it is known that Pakistan–along with many other nuclear-armed states–is modernizing its nuclear capabilities and fielding new weapons systems, little official information has been released regarding these plans or the status of its arsenal.

One of the many questions researchers have been asking concerns the modernization of Pakistan’s nuclear-capable aircraft and its associated air-launched cruise missiles (ALCM). It has been long assumed that the Mirage III and Mirage V fighter bombers are the two aircraft with a nuclear delivery role in the Pakistan Air Force (PAF). The Mirage V is thought to have a strike role with Pakistan’s limited supply of nuclear gravity bombs, while the Mirage III has been used to conduct test launches of Pakistan’s dual-capable Ra’ad-I (Hatf-8) ALCM, as well as the follow-on Ra’ad-II. The Ra’ad ALCM was first tested in 2007 and has since remained Pakistan’s only nuclear-capable air-launched cruise missile.

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) reported in 2017 that the Ra’ad cruise missile was “conventional or nuclear,” a term normally used to describe a dual-capable system.

In order to retire its aging Mirage III and V aircraft and bolster defense production, Pakistan has procured over 130 operational JF-17 aircraft–which are jointly produced with China–and plans to acquire more in the future. During the 2024 Pakistan Day Parade, the PAF also announced a JF-17 PFX (Pakistan Fighter Experimental) project to maximize the operational lifespan and modernize the capabilities of the JF-17 aircraft.

Over the past few years, several reports have suggested Pakistan may incorporate the dual-capable Ra’ad ALCM onto the JF-17 so that the newer aircraft could eventually take over the nuclear strike role from the Mirage III/Vs. However, little information has been revealed about the status of this procurement and whether the JF-17s will replace the Mirage III and Vs in the nuclear mission. That is, until March 2023, when an aviation photographer captured an image that could help answer some of these lingering questions.

A possible new nuclear mission

During rehearsals for the 2023 Pakistan Day Parade (which was subsequently canceled), an image surfaced of a JF-17 Thunder Block II carrying what was reported to be a Ra’ad ALCM. Notably, this was the first time such a configuration had been observed in public.

Photo credit: Rana Suhaib/Snappers Crew

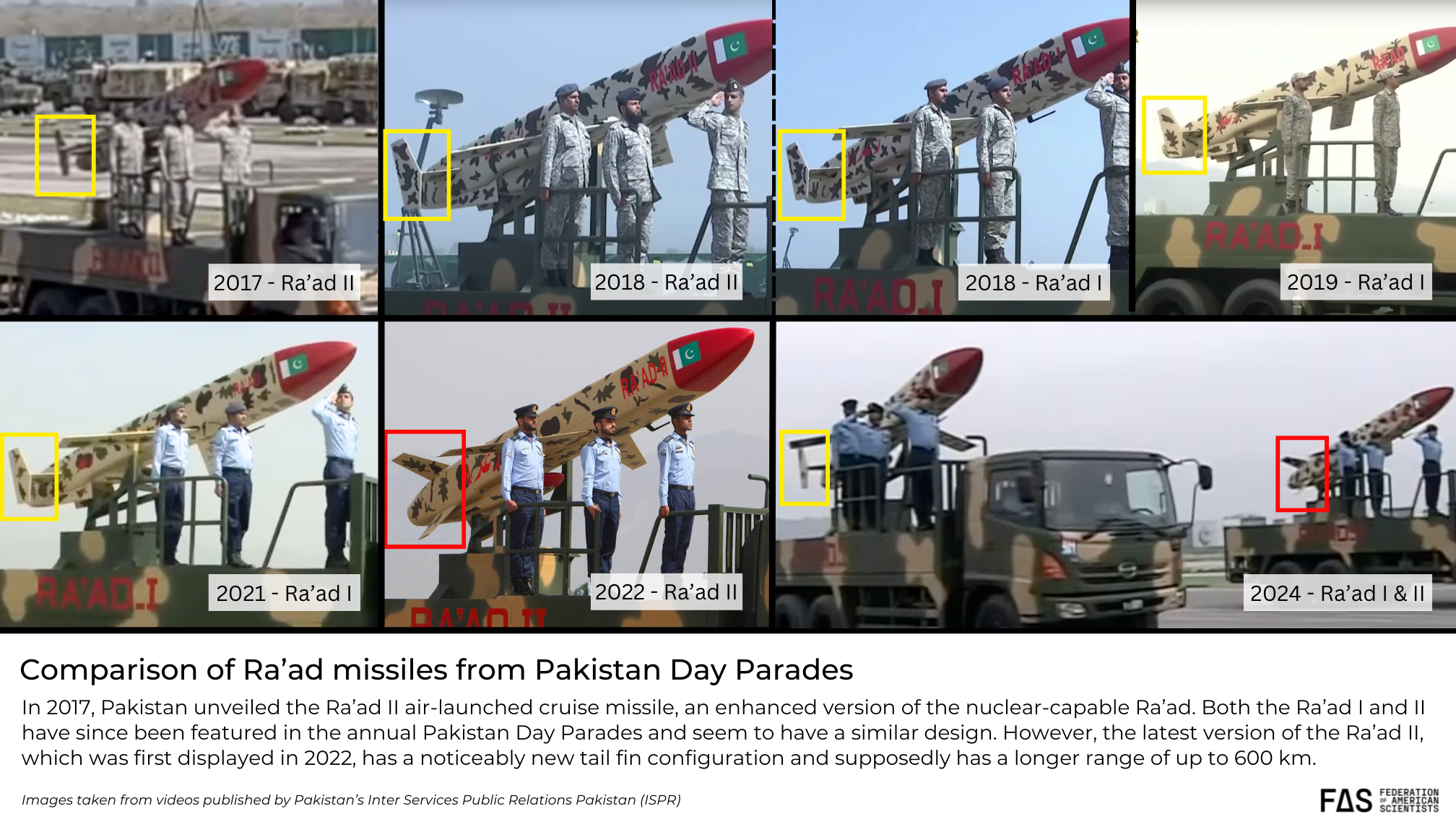

FAS was able to purchase the original image. To try and ascertain which type of Ra’ad is in the JF-17 image–the original Ra’ad-I or the extended-range Ra’ad-II–we compared it to other Ra’ad-I and -II missiles displayed in the 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2024 Pakistan Day Parades (the parades in 2020 and 2023 were canceled) where the Ra’ad-I and Ra’ad-II were showcased alongside other nuclear-capable missiles such as the Nasr, Ghauri, Shaheen-IA and -II, as well as the Babur-1A.

Between 2017–when the Ra’ad-II was first publicly unveiled–and 2022, there were very few observable differences between the Ra’ad-I and -II. During this period, both missiles featured a new engine air intake, and although the Ra’ad-II was presented as having nearly double the range capability, this was not clearly observable through external features.

In 2017, Pakistan unveiled the Ra’ad Il air-launched cruise missile, an enhanced version of the nuclear-capable Ra’ad. Both the Ra’ad I and II have since been featured in the annual Pakistan Day Parades and seem to have a similar design. However, the latest version of the Ra’ad II, which was first displayed in 2022, has a noticeably new tail fin configuration and supposedly has a longer range of up to 600 km.

However, in 2022, a new version of the Ra’ad-II was displayed at the 2022 Pakistan Day Parade. Notably, this new version had an ‘x-shaped’ tail fin configuration as opposed to the other ‘twin-tail’ configurations seen in previous versions of the missile. The subsequent 2024 Pakistan Day parade also showcased the two distinct versions of the Ra’ad with their respective tail fin arrangements.

The fin arrangements of the photographed missile on the JF-17 appear to more closely match the ‘twin-tail’ configuration of the Ra’ad-I, rather than the newer ‘x-shaped’ tail of the Ra’ad-II, especially since it is unlikely that an outdated version of the Ra’ad II would be utilized in a flight test intended to demonstrate state-of-the-art capabilities.

Pakistan is also developing a conventional, anti-ship variant of the Ra’ad ALCM, known as Taimoor, that can be launched from the JF-17. Photos of the missile indicate that the two designs are highly similar, although the Taimoor missile also appears to include an ‘x-tail’ fin configuration, and its length is reported to be 4.38 meters. The ‘x-tail configuration’ would appear to indicate that the missile photographed on the JF-17 was not the Taimoor; however, for additional clarity, we measured multiple parade images of both versions of the Ra’ad and compared their lengths to that of the photographed missile.

We took an image of the Ra’ad-I from the 2019 Pakistan Day Parade and used the Vanishing Point feature in Photoshop to add gridded planes that simulate a 3D space in order to account for the angle at which the image was taken and the depth at which the missile sits compared to the side of the truck. After finding the make and model of the vehicle carrying the missile (which appears to be an early version of the Hino 500 Series FM 2630), we used the truck’s trailer axle spread of approximately 1.3 meters and wheelbase of 4.24 meters reference values and used Photoshop’s measuring tool to render an approximate length. We found it to be around 4.9 meters.

To estimate the dimensions of the Ra’ad-II, we started with a photo from the 2022 Pakistan Day Parade. Using the same methodology with Photoshop’s Vanishing Point tool to account for the angle of the photo and the distance from the missile’s position in the center of the vehicle to the foremost gridded plane that measures the length of the truck, we roughly estimated the size of the missile to be around 4.9 meters.

We also double-checked the dimensions of the cruise missile in the JF-17 image. Since we know that the JF-17 is roughly 14.3 meters long, we used that number as a reference value and employed Photoshop’s Vanishing Point and measuring tool again to render an approximate length of the missile, given its lowered position in relation to the edge of the fuselage. The result was 4.9 meters, which matches the reported dimensions of the Ra’ad-I and -II ALCM as well as our estimated measurements. This measurement is also longer than the Taimoor’s reported 4.38-meter length.

While it is possible that the missile could be an old Ra’ad-II, given that the 2017 version also had a ‘twin-tail’ configuration, that version of the Ra’ad-II appears to be outdated and is therefore unlikely to be utilized in a flight test. Still, it is possible that more information, images, or statements from the Pakistan government could surface that answer some of these questions.

Observing the differences between the Ra’ad-I and Ra’ad-II missiles raises a few questions. How was Pakistan able to nearly double the range of the Ra’ad from an estimated 350 km to 550 km and then to 600 km for the newest version without noticeably changing the size of the missile to carry more fuel? The answer could possibly be that the Ra’ad-II engine design is more efficient, the construction components are made from lighter-weight materials, or the payload has been reduced.

These measurements offer additional evidence to support our conclusion that the missile observed in the photographed image of the JF-17 is the Ra’ad-I ALCM.

Implications for Pakistan’s nuclear forces

Given the lack of publicly available information from the government of Pakistan about its nuclear forces, we must rely on these types of analyses to understand the status of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. From these observations, it is likely that Pakistan has made significant progress toward equipping its JF-17s with the capability to eventually supplement–and possibly replace–the nuclear strike role of the aging Mirage III/Vs. Additionally, it is evident that Pakistan has redesigned the Ra’ad-II ALCM, but little information has been confirmed about the purpose or capabilities associated with this new design. It is also unclear whether either of the Ra’ad systems has been deployed, but this may only be a question of when rather than if. Once deployed, it remains to be seen if Pakistan will also continue to retain a nuclear gravity bomb capability for its aircraft or transition to stand-off cruise missiles only.

This all takes place in the larger backdrop of an ongoing and deepening nuclear arms competition in the region. Pakistan is reportedly pursuing the capability to deliver multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) with its Ababeel land-based missile, while India is also pursuing MIRV technology for its Agni-P and Agni-5 missiles, and China has deployed MIRVs on a number of its DF-5B ICBMs and DF-41. In addition to the Ra’ad ALCM, Pakistan has also been developing other short-range, lower-yield nuclear-capable systems, such as the NASR (Hatf-9) ballistic missile, that are designed to counter conventional military threats from India below the strategic nuclear level.

These developments, along with heightened tensions in the region, have raised concerns about accelerated arms racing as well as new risks for escalation in a potential conflict between India and Pakistan, especially since India is also increasing the size and improving the capabilities of its nuclear arsenal. This context presents an even greater need for transparency and understanding about the quality and intentions behind states’ nuclear programs to prevent mischaracterization and misunderstanding, as well as to avoid worst-case force buildup reactions.

The author would like to thank David La Boon and Decker Eveleth for their invaluable guidance and feedback on using Photoshop’s Vanishing Point feature.

Correction: After the article’s publication, the final image was removed and replaced with the correct image. The language and conclusions of the piece remained unchanged.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.