(Mathematically) Predicting the Future with Professional Forecaster Philipp Schoenegger

Right now, working alongside the Federation of American Scientists, the forecasting platform Metaculus is hosting its first ever Climate Tipping Points Tournament. The aim is to show just how powerful a tool forecasting can be for policymakers trying to effect change.

Part of what makes the Metaculus forecasting community exciting is that anyone with even a passing interest in data science can jump in and begin making predictions; the wisdom of the growing crowd of forecasters helps make the platform more and more accurate over time.

Metaculus has recruited about two dozen of the very best forecasters in its community to become Pro Forecasters. To become a Pro for Metaculus, a forecaster has to have scores in the top 2% of all Metaculus users. The Metaculus scoring system is complex, but for the mathematically-disinclined, you earn points on accuracy, how your prediction compares to those of the rest of the Metaculus community, and how early you make your predictions (in relation to the resolution of the question). Pro Forecasters also have experience forecasting for at least a year, and have a history of providing commentary explaining their methodology.

Philipp Schoenegger became one of the first members of the pro-forecasting team last year – and says he’s been forecasting for about a year and a half in total.

“Right now I have about 6,000 forecasts on the Metaculus platform,” he says. “I think what goes into forecasting questions, time-wise, can vary widely between professional forecasting and hobbyist forecasting.”

Schoenegger, who recently defended his PhD thesis in behavioral economics and experimental philosophy at the University of St. Andrews, says over the past couple of years he found himself spending what he calls an “excessive” amount of time on forecasting – at times to the detriment of his studies or other work. Luckily, the people at Metaculus recognized his talent, and invited him to join the pro forecasting team for its Forecasting Our World in Data project.

Schoenegger says part of what he enjoys about forecasting on the pro team is the incentive to explain and share methodology. In public tournaments, he says, there’s always a tension between collaboration with the community – and winning.

“The cool thing about the professional forecasting tournaments is the sharing of information and writing out rationale is part of what we are incentivized to do. I think that’s really fun,” he says. He also loves reading about how other pro forecasters think. “I find that very useful and helpful, especially when they do things very differently from me. The Pro Forecasters vary widely in our backgrounds and approaches. Some people are 50-plus and have a long history of doing this professionally. Other people are just out of their PhDs. Some people forecast just for Metaculus, but also have another very unrelated job.”

But how does he do things? How does he feel confident offering up predictions on everything from when Queen Elizabeth II’s reign would end, to whether a major nuclear power plant will be operational in Germany by this summer?

“The way I do it is with just very basic simple models – but those models are never more than 50% of what my actual forecast looks like,” he says. The other 50%, he says, is all the background research and extra information he can find on the given subject – additional factors that could influence an outcome. “The very simple models then take a backseat to the background reading, and understanding certain types of risks.”

He returns to the example of Queen Elizabeth II. If you were trying to predict when her reign would end [the queen died in September of 2022, but Metaculus first posed its question in January of 2020], Schoenegger says you would start with base rates on basic questions. “How often do British monarchs abdicate? Or I think the most basic question would be, ‘What’s average life expectancy?’ And looking at her age you might say there’s a 20% chance she dies each year after 2018. But then you might look at her track record of very good health, and update your numbers. And then you might read some article or argument in the other direction, and update depending on how credible you think it is.”

For the Climate Tipping Points tournament, some of the questions center on the availability of certain resources for electric vehicle technology. “It has to do with resources, and scarcity, and when those might be alleviated. The way I approached this was to just try to read a bunch of different [articles and reports] that try to look at those specific sub-questions – like precious metals or lithium supply, or stuff like that.”

And while sharing his methodology is part of the job now – at the outset of a question or tournament, Schoenegger says he guards against his forecasts being influenced by others in the Metaculus forecasting community. “On this tournament, I made an effort to be done with all my work on day one. I wanted to make sure that I get all my numbers into the system first, so I’m not then swayed by other people.”

Though Schoenegger obviously has a good track record as a forecaster now – he’s also very open to the possibility that things could change.

“I think the honest answer – and there are other people and forecasters who might give different, more optimistic answers – but I just think we don’t know yet if my track record over the past 18 months is actually at all predictive of me actually being better [than the average forecaster] over the next 40 years. I honestly think we don’t know yet,” he says.

But that uncertainty doesn’t mean Schoenegger is shy about getting more people to try their hands at predicting the future in an evidence-based way.

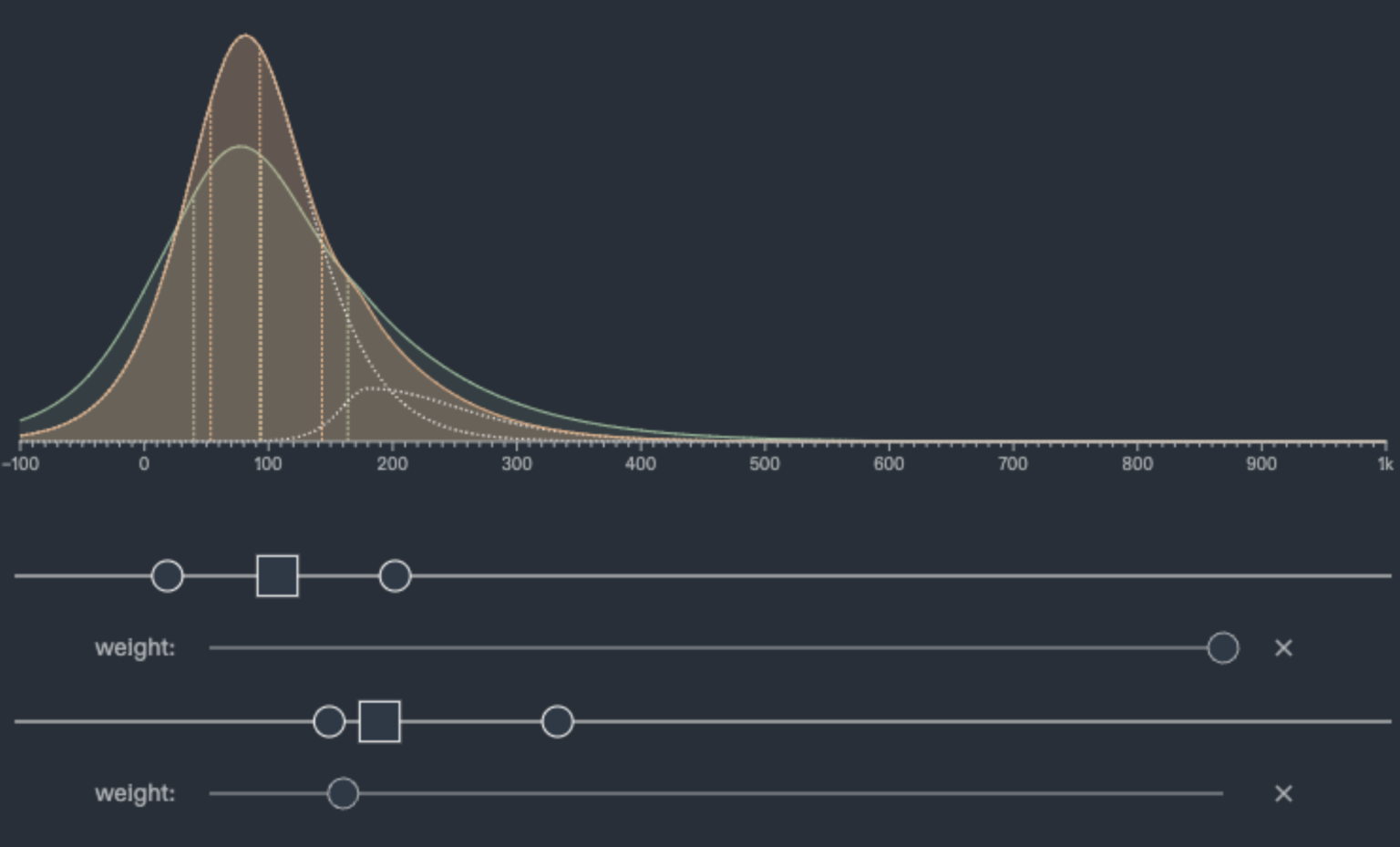

He says he’s twisted the figurative arms of ‘half of my family and most of my friends’ into making at least one official forecast. He tells people new to forecasting to start with a question or topic that they already have some interest or expertise in. “Take a look and try to flesh out your thinking and feelings in actual numbers and distributions and dates, because that’s something that most people don’t do. ‘It is very likely.’ What exactly do you mean by that? And I think just that exercise of putting fuzzy feelings into actual numbers – I think that can be very illuminating for oneself.”

And what of the future of forecasting more generally? Schoenegger believes that while specialized research labs with a group of experts investigating a single issue area will likely always have an advantage over crowdsourced platforms like Metaculus – it will be true only in their specific areas of study.

“If you have your proprietary super special model, and ten research scientists work on it – it’s very good for some parametric insurance about floods in Turkey or something like that,” he says. “But [for Metaculus] I think it’s the speed and agility with which you can forecast. The war in Ukraine, climate, presidential elections, something about some king or queen – it’s very broad. And the hope is that once you hit a certain number of dedicated users who continually forecast on those things, with the wisdom of the crowds, you can actually have forecasts on all sorts of stuff. And I think they might underperform the hyper-specialized $10 million model on its specific thing. But [the crowdsourced forecasting] will win on pretty much everything else.”

Schoenegger says he’s not positive he wants professional forecasting to be his main focus forever, but he’s also loath to give it up. “I’m still undecided on going the route of forecasting as my main job, or academics as my main job,” he says. “I think what I end up doing is basically both – because I like forecasting way too much. It’s way more fun than writing papers, to be honest.”

FAS is launching the Center for Regulatory Ingenuity (CRI) to build a new, transpartisan vision of government that works – that has the capacity to achieve ambitious goals while adeptly responding to people’s basic needs.

This runs counter to public opinion: 4 in 5 of all Americans, across party lines, want to see the government take stronger climate action.

Cities need to rapidly become compact, efficient, electrified, and nature‑rich urban ecosystems where we take better care of each other and avoid locking in more sprawl and fossil‑fuel dependence.

Hurricanes cause around 24 deaths per storm – but the longer-term consequences kill thousands more. With extreme weather events becoming ever-more common, there is a national and moral imperative to rethink not just who responds to disasters, but for how long and to what end.