Report: When Ambition Meets Reality — Lessons Learned in Federal Clean Energy Implementation, and a Path Forward

The Trump administration has scrapped over $8 billion (so far) in grants for dozens of massive clean energy projects in the United States. For those of us who worked on the frontlines of Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) implementation, the near-weekly announcements and headlines have been maddening, especially at a time when many of these projects would have helped address soaring electricity prices and surging demand growth.

While some of these cancellations were probably illegal, they nevertheless raise fundamental questions for clean energy advocates: why was so much money still unspent…and why was it so easy to cancel?

In a new report, we begin to address these fundamental implementation questions based on discussions with over 80 individuals – from senior political staff to individual project managers – involved in the execution of major clean energy programs through the Department of Energy (DOE).

Their answer? There is significant opportunity – as our colleagues at FAS have written – for future Executive branch implementation to move much faster and produce much more durable results. But to do so, future implementation efforts must look drastically different from the past, with a ruthless focus on speed, outcomes, and the full use of Executive Branch authorities to more quickly get steel in the ground.

The risk of risk aversion

Take the grant cancellations example. The Trump administration has relied on one small clause in the Code of Federal Regulations (2CFR 200.340(a)(4)) as the legal basis for its widespread cancellations. This clause, traditionally included in most grants between the government and a private company, allows the government to cancel any grant that “no longer effectuates the program goals or agency priorities” and essentially functions as a “termination for convenience” clause.

But including this “termination for convenience” clause was optional. DOE could have leveraged a different, more flexible contracting authority for many awards. It also could have processed what’s known as a “deviation” in order to exclude the clause from standard contracts. Leaders of program offices were aware of these options, with some staffers strenuously objecting to the inclusion of termination for convenience.

But in the end, DOE offices generally opted to keep this clause because it was the way the agency had always executed (primarily R&D) grants in the past, and because sticking to established procedures was seen as the best way to avoid the risk of Congressional or Inspector General oversight.

And yet, this risk-averse approach perversely increased the risk of project failure, by creating an easy kill switch for an administration looking for grounds on which to cancel particular projects.

This attitude toward risk – which saw defaulting to the status quo as the most prudent path – was a constant barrier to effective implementation. (In addition to opening up grants to cancellation, the embrace of 2CFR 200 regulations meaningfully slowed negotiations as companies bristled at the obscure accounting and other compliance measures the regulations would impose on them.)

Understanding this culture of risk aversion offers two takeaways for improving government: (1) rigorously question status quo decisions and avoid defaulting to agency precedent and (2) avoid excessive focus on eliminating every risk or avoiding external backlash or oversight (especially given that backlash and oversight are likely regardless of the approach.)

Speed is paramount

Of course, excluding the termination for convenience clause would not have been a panacea. It’s likely the Trump administration would have devised some other pretext for cancelling the grants that may have been just as successful, though perhaps legally shakier.

That’s why implementers also told us that speed is critical. The best defense is a strong offense. And the best way to prevent money from being taken back is to have already spent it on promising projects. The federal government has moved faster in implementation of large policies before. During the New Deal, the Tennessee Valley Authority moved from passage of its founding law to beginning construction on a major dam in just four months. Operation Warp Speed delivered cutting-edge life-saving vaccines to millions of Americans in about a year. While the contexts and goals of these programs were different, we know from history that the federal government can move fast.

But at DOE, only 5% of the funds appropriated through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law had actually been spent (not just obligated) by the time the Biden administration ended three years later. In addition to making clean energy projects more vulnerable to subsequent cancellations, the pace of the rollout meant that the basic political hypothesis animating clean energy legislation—that the economic development projects brought, especially to red states, would create a durable bipartisan coalition for clean energy—went untested.

Practically everyone we spoke with expressed frustration at the slow pace of implementation. Interviewees highlighted many challenges associated with a relatively slow pace of BIL and IRA implementation, such as:

- “Too many cooks” dynamics at every level of implementation.

- A lack of coalitional policy prioritization.

- Overcomplicated award processes.

- Regulatory compliance issues that were at odds with industry realities. (Davis-Bacon, NEPA, Build America Buy America, and the Paperwork Reduction Act were those most frequently mentioned.)

The work begins now

One commonality between these and other issues identified in our report is encouraging: they are mostly within the Executive Branch’s power to solve. A sufficiently prepared future administration could address many of these challenges for future federal clean energy efforts without relying on the vagaries of the legislative process. But the work must begin now.

On contracting, for instance, a future administration’s DOE could make better use of Other Transactions Authority for clean energy. But it should be prepared with drafts of the basic commercial terms of agreements between the government and companies it works with. Similarly, a proactive future administration will come in with a clear view on how to streamline compliance with environmental, prevailing wage, domestic sourcing, and other cross-cutting requirements. On decision-making, a future administration can set norms pushing decision-making to the lowest possible level, clarify processes to elevate and execute major issues, and establish small, clear, and empowered teams that own frontline negotiations.

If pursued, this updated approach to federal clean energy implementation will look drastically different. But one way or another it will have to: the next time there is a federal government interested in accelerating clean energy, it is likely to be dealing with a private sector much more wary of working with the government, fiscal constraints that limit the likely scale of any clean energy funding, and a dramatically altered federal workforce and state apparatus.

Much can be done outside of the federal government — including at state and local levels — to prepare for those circumstances. It is possible for a future federal administration to achieve faster and more durable clean energy outcomes. But to make that possible, the work must begin now.

It’s not enough to say we need to make full use of DOE’s authorities; we need the drafted Secretarial directives and advance legal legwork to do it, and leadership well-equipped with the details and government-insider knowledge to execute on it.

It’s not enough to say we want more nuclear, transmission, or critical minerals projects; we need to have identified the priority projects and designed the strategies and programs needed to actually put them in motion on Day 1.

It’s not enough to say we should take a “whole-of-government” approach to an issue like clean energy; we need a detailed plan for how to use the $5 billion/year in electricity purchases and the PMA’s 45,000 miles of transmission lines—all under the direct control of the federal government—to achieve explicit policy outcomes.

And it’s not enough to say we need to rebuild the federal workforce; we need a roster of hundreds of people that can be brought on and trained rapidly to implement within weeks.

To live up to the spirit of the New Deal and Operation Warp Speed—the spirit that turned ambitious goals into massive real-world impact in a matter of months—the next administration must come armed not only with broad aspirations, but also with the detailed plans required to implement them.

Want abundant energy? Ask who benefits from scarcity.

This article originally was published July 30 on Utility Dive.

A new obsession with abundance is spreading through policy conversations and governors’ mansions across the country. Abundance advocates, boosted by a recent book from Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, envision a future in which we defeat the climate crisis, reduce cost of living and improve quality of life by speeding up construction of housing and energy infrastructure.

Making clean energy abundant is certainly critical to addressing the climate crisis. We need plentiful, cheap, clean energy to replace polluting fossil fuels in buildings, vehicles and factories. As a senior policy advisor in the Biden White House, I worked on many policies aimed at clean energy abundance, directly or indirectly, and I also saw firsthand how those policies were insufficient. That’s why it is now clear to me that the abundance movement’s playbook — to streamline permitting, simplify government processes and make public investments more focused — falls short of what’s needed.

We won’t achieve energy abundance unless we contend with the powerful interests that benefit from scarcity. Doing so requires reforming electricity markets, refreshing regulation of electric companies and rethinking the way we pay for grid infrastructure.

Let’s start with the problem: we are not building nearly enough clean energy to curb climate change and keep electricity affordable. Analysis from three leading research projects found that for us to get within striking distance of the Paris climate goals and plan for the lowest electricity costs, we must build 70 GW to 125 GW of clean energy per year, much higher than the record 50 GW built in 2024. As a result of our failure to build new energy projects fast, families and businesses will pay more for power and the planet will warm faster.

This is no longer an economic issue. Clean electricity is now often cheaper to deploy than new coal and gas, and in many cases cheaper than existing fossil-fuel-fired power plants. So what is stopping us from building it fast enough?

To answer this question, abundance proponents, including Klein and Thompson, largely focus on two main obstacles: 1) opposition from people who live nearby specific projects and groups concerned with local environmental impacts and 2) “everything-bagel liberalism,” the tendency to add too many strings to government incentives. The solution to the first problem, they argue, is to limit the power of the opposition by streamlining federal permitting and constraining public input in state and local siting processes. And for the second, their remedy is to limit the number of goals of government programs and reduce the requirements for funding.

There is no doubt that some clean energy and transmission projects have been thwarted by local opposition and lengthy litigation. And it is a worthy goal to make government incentives as effective as possible. But by portraying the primary villains defending scarcity as local landowners, conservation groups and the diversity of the liberal coalition, Klein and Thompson ignore important characters and policies that, if left unchecked, will continue to hamstring the pursuit of abundance.

For example, consider the situation unfolding in the electricity market organized by the PJM Interconnection, which operates the electricity grid for 65 million people in 13 mid-Atlantic and midwestern states and Washington, D.C. An independent, non-governmental entity, PJM runs the process to connect new power plants to the grid, among other important processes to make the electricity system work. PJM has been notoriously bad at this job. It ranks as the worst grid operator in the country in terms of the speed and effectiveness of its interconnection process. The average project waits five years for PJM to give it permission to connect to the grid. In fact, PJM closed its doors to new project applications in 2022 and has yet to re-open it. As a result, electricity demand is outpacing supply, prices are rising rapidly, and new clean energy projects are dying as they wait for word from PJM.

PJM has the power to speed up the process to connect new projects, which would increase electricity supply and cut electricity prices. But PJM has largely resisted reforms and focused instead on extending the life of existing power plants. Here is where it is helpful to ask: who benefits from an electricity shortage and the resulting high prices? It is not conservation groups or liberal stakeholder groups with competing goals (who have no voting power in PJM’s governance structure). It is the incumbent utilities that own the fleet of aging coal-fired power plants, which are struggling to compete with new clean energy projects. If cheap clean energy is allowed to enter the market, these companies will make less money. The outdated processes for approving new projects help prevent cheaper energy resources from threatening their business model. The companies have significant decision-making power — together, power plant owners, transmission owners (many of whom also own generation) and other energy service suppliers make up 60% of the voting power in PJM decisions.

Energy will not be abundant in the mid-Atlantic unless we take on the interests that are benefitting from scarcity. That means reforming the electricity market to stop overpaying existing power plants at the expense of customers, changing the rules to make it easier to connect new power plants to the grid and updating governance structures to make sure that customers are properly represented.

Similar cases abound of powerful interests benefitting from scarcity and defending policies that prevent abundance. Monopoly utilities, for example, benefit from abundant energy to the extent that they can build it and can earn a return on their investments — but not if the energy comes from their competition. That’s why utilities in the southeast have gone to great lengths to block transmission lines that enable cheap clean energy to compete with their existing power plants. Changing how those utilities make money (for example, by paying for outcomes instead of investments) could flip the script and turn the utilities into energy abundance advocates.

If the abundance movement is to succeed, it must identify the defenders of scarcity and broaden the playbook to either overcome those interests or change their incentives to bring them on the team.

Beyond Binary Debates: How an “Abundance” Framing Can Restore Public Trust and Guide Climate Solutions

Public trust in U.S. government has ebbed and flowed over the decades, but it’s been stuck in the basement for a while. Not since 2005 have more than a third of Americans trusted the institution that underpins so much of American life.

We shouldn’t be surprised. Along with much progress, over the past two decades the U.S. became more unequal, saw stagnation or decline in many rural counties, stumbled into a housing crisis, and experienced worsening health outcomes. When the government can’t deliver (especially in core areas like health, housing, and economic vitality), trust in it wanes while the false promises of autocrats grow more appealing.

The strength of American democracy, in other words, hinges in large part on how well our government functions. This urgency helps explain why, at a moment when the United States is flirting with autocracy ever more vigorously, a book on precisely this topic became a #1 bestseller and prompted a debate around the “abundance agenda” that has turned quasi-existential for many in the policy world.

The abundance agenda, as described by Jonathan Chait, is “a collection of policy reforms designed to make it easier to build housing and infrastructure and for government bureaucracy to work”, such as by streamlining regulations that constrain infrastructure buildout while scaling up major government programs and investments that can deliver public goods.

Unfortunately, popular discourse often flattens the conversation around abundance into a polarized binary around whether or not regulations are good. That frame is overly reductionist. Of course badly designed or out-dated regulatory approaches can block progress or (as in the case of the housing policies that the book Abundance centers on) dry up the supply of public goods. But a theory of the whole regulatory world can’t be neatly extrapolated from urban zoning errors. In an era of accelerating corporate capture, both private and public power structures act to block change and capture profits and power. We need a savvier understanding of what happens at the intersections between the government and the economy, and of how policy translates to communities at local scales.

We should therefore regard “abundance” less as a prescriptive policy agenda than as a frame from which to ask and answer questions at the heart of rebuilding public trust in government. Questions like: “Why is it so hard to build?” “Why are bureaucratic processes so badly matched to societal challenges?” “Why, for heaven’s sake, does nothing work?”

These questions can push us in a direction distinct from the usual big vs. small government debates, or squabbles about the welfare state versus the market. Instead, they may help us ask about interactions within and between government and the economy – the network of relationships, complex causation, and historical choices – that often seem to have left us with a government that feels ill-suited to its times.

At the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), we, along with colleagues in the broader government capacity movement, are exploring these questions, with a particular focus on agendas for renewal and advancing a new paradigm of regulatory ingenuity. One emerging insight is that at its core, abundance is largely about the dynamics of incumbency, that is, about the persistence of broken systems and legacy power structures even as society evolves. A second, related, insight is that the debate around abundance isn’t really about de-regulation or the regulatory state (every government has regulations), but rather about how multi-pronged and polycentric strategies can break through the inertia of incumbent systems, enabling government to better deliver the goods, services, and functions it is tasked with while also driving big and necessary societal changes. And a third is that the abundance discourse must center distributive justice in order to deliver shared prosperity and restore public trust.

Moving the Boulder: Inertia, Climate Change, and the Mission State

The above insights are particularly helpful in guiding new and more durable solutions to climate change – a challenge that touches every aspect of our society, that involves complex questions of market and government design, and that is rooted in the challenges of changing incumbent systems.

Consider the following. It’s now been almost 16 years since the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued its 2009 finding that greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are a public danger and began trying to regulate them. To simplify a complex history, what happened on the regulatory front was this: the Obama administration tried to push regulations forward, the Trump administration worked to undo them, and then the cycle repeated through Biden and Trump II, culminating in the EPA’s recent move to revoke the endangerment finding.

We can certainly see the power of incumbency and inertia within this history. Over a decade and a half, the EPA regulated greenhouse gases from new power plants (though never very stringently), new cars and trucks (quite effectively cutting pollution, though never with mandates to actually electrify the fleet), and…that’s about it. The agency never implemented standards for the existing power plants and existing vehicles that emit the lion’s share of U.S. GHGs. It never regulated GHGs from industry or buildings. And thanks to the efforts of entrenched fossil-fuel actors and their political allies, the climate regulations EPA managed to get over the finish line were largely rolled back.

None of this should be read as a knock on the dedicated civil servants at EPA and partner federal agencies who worked to produce GHG regulations that were scientifically grounded, legally defensible, technically feasible, and cost effective, even while grappling with the monumental challenges of outdated statutes and internal systems. But it certainly speaks to the challenge of securing lasting change.

The work of economist Mariana Mazzucato offers clues to how we might tackle this challenge; she paints a portrait of a “mission state” that integrates all of government’s levers to define and execute a particular objective, such as an effective, equitable, and durable clean energy transition. This theory isn’t a case for simplistic deregulation, nor is it a claim that regulations somehow “don’t work”. Rather, it suggests that (especially in a post-Chevron world) another round of battles over EPA authority won’t ultimately get us where we need to go on climate, nor will it help us productively reshape our institutions in ways that engender public trust.

The shift from one energy system foundation to another is messy – and it is inherently about power. As giant investment firms hustle to buy public utilities, enormous truck companies side with the Trump administration to dismantle state clean freight programs, and subsidies for clean energy are decried as unfair and market-distorting even though subsidies for fossil energy have persisted for nearly a century, it’s clear that corporate incumbents can capture public investments or capture government power to throttle change. Delivering change means thinking through the many ways incumbency creates systems of dependencies throughout society, and what options – from regulations to monetary policy to the ability to shape the rule of law – we have to respond. To disrupt energy incumbents and achieve energy abundance, in other words, we must couple regulatory and non-regulatory tools.

After all, the past 16 years haven’t just been a story of regulatory back-and-forth. They are also a story of how U.S. emissions have fallen relatively steadily in part due to federal policies, in part to state and local leadership, and in part to ongoing technological progress. Emissions will likely keep falling (though not fast enough) despite Trump-era rollbacks. That’s evidence that there’s not a one-to-one connection between regulatory policy and results.

We also have evidence of how potent it can be when economic and regulatory efforts pull in tandem. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was the first time the United States strongly invested in an economic pivot towards clean energy at scale and in a mission-oriented way. The results were immediate and transformative: U.S. clean energy and manufacturing investments took off in ways that far surpassed most expectations. And while the IRA has certainly come under attack during this Administration, it is nevertheless striking that today’s Republican trifecta retained large parts of the entirely Democratically-passed IRA, demonstrating the sticking power of a mission-oriented approach.

Conducting the Orchestra: The Need for an Expanded Playing Field

Thinking beyond regulatory levers (i.e., a multi-pronged approach) is necessary but not sufficient to chart the path forward for climate strategy. In a highly diverse and federalist nation like the United States, we must also think beyond federal government entirely.

That’s because, as Nobel-winning economist Dr. Elinor Ostrom put it, climate change is inherently a “polycentric” problem. The incumbent fossil systems at the root of the climate crisis are entrenched and cut across geographies as well as across public/private divisions. Therefore the federal government cannot effectively disrupt these systems alone. Many components of the fundamental economic and societal shifts that we need to realize the vision of clean energy abundance lie substantially outside sole federal control – and are best driven by the sustained investments and clear and consistent policies that our polarized politics aren’t delivering.

For example, states, counties, and cities have long had primary oversight of their own economic development plans, their transportation plans, their building and zoning policies, and the make-up of their power mix. That means they have primary power both over most sources of climate pollution (two-thirds of the world’s climate emissions come from cities) and over how their economies and built environments change in response. These powers are fundamentally different from, and generally much broader than, powers held by federal regulatory agencies. Subnational governments also often have a greater ability to move funds, shape new complex policies across silos, and come up with creative responses that are inherently place-based. (The indispensable functions of subnational governments are also a reason why decades of cuts to subnational government budgets are a worryingly overlooked problem – austerity inhibits bottom-up climate progress.)

The private sector has similar ability to either constrain or drive forward new economic pathways. Indeed, with the private sector accounting for about half of funding for climate solutions, it is impossible to imagine a successful clean-energy transition that isn’t heavily predicated on private capabilities – particularly in the United States. While China’s clean-tech boom is largely the product of massive top-down subsidies and market interventions, a non-communist regime must rely on the private sector as a core partner rather than a mere executor of climate strategy. Fortunately, avenues for effectively engaging and leveraging the private sector in climate action are rapidly developing, including partnering public enterprise with private equity to sustain clean energy policies despite federal cutbacks.

An orchestra is an apt analogy. Just as many instruments and players come together in a symphony, so too can private and public actors across sectors and governance levels come together to achieve clean energy abundance. This analogy extends Mazzucato’s conception of a mission state into a “mission society”, envisioning a network that spans from cities to nation states, from private firms to civil actors, working in concert to overcome what Ben Rhodes calls a “crisis of short termism” and deliver a “coherent vision” of a better future.

Building Towards Shared Prosperity

For the vision to be coherent, it must resonate across socioeconomic and ideological boundaries, and it must recognize that the structures of racial, class, and gender disparity that have marked the American project from the beginning are emphatically still there. Such factors shape available pathways for progress and affect their justice and durability. For instance: electric vehicle adoption can only grow so quickly until we make it much easier for those living in rented or multifamily housing to charge. Cheaper renewables only mean so much when prevailing policies limit the financial benefits that are passed on to lower-income Americans.

To borrow, and complicate, a metaphor from Abundance: distributive justice questions are fundamentally not “everything bagel” seasonings to be disregarded as secondary to delivery goals. They are meaningful constraints on delivery as well as critical potentialities for better systems, and are hence central to policy and politics. No mission state or mission nation, addressing the polycentric landscape of networked change needed to shift big incumbent systems, can afford to dismiss or ignore them. Displacing those systems requires wrestling with inequality and striving to create shared prosperity through new approaches that are distributively fair.

That’s an approach rooted in orchestration, one that asks why some instruments drown out others, and how to alter relationships between players to produce better results. It understands that we can’t solve scarcity without centering distributive justice, because as long as deep structural disparities and structural power exist there is strong potential for the benefits of rapid energy or housing buildout to be channeled towards those who need them least. And it is capable of restabilizing the center of American society and restoring trust in U.S. government because it realistically grapples with the interests of incumbents while paying more than lip service to the interests of a dazzlingly diverse American public.

This re-fashioned abundance agenda can provide actual principles for administrative state reform because it knows what it is asking regulators, and the larger intersecting layers of government and civil society, to do: Systematically remove points of inertia to accelerate shared prosperity in a safe climate, while anticipating and solving for distributive risks of change.

Because again, the abundance debate isn’t really about whether or not regulations are good. It’s about unfreezing our politics by being clear and courageous about our goals for a society that works better and is capable of big things.

This is not the first time Americans have envisioned a better future in the midst of national crisis, or the first time we have collectively disrupted failed incumbent systems. From our messy foundation, to the beginnings of Reconstruction during the Civil War, to the architects of the New Deal envisioning an active and effective government in the midst of the Dust Bowl and Depression, the history of our nation is full of evidence that a compelling vision of truly democratic government can pull Americans back together despite deep and real problems. Each time, these debates have scrambled existing binaries, and driven realignment. We are on the verge of realignment again as the systems built up over the fossil era break down and our neoliberal order fragments. This is the right time to engage, together, in orchestrating what comes next.

De-Risking the Clean Energy Transition: Opportunities and Principles for Subnational Actors

Executive Summary

The clean energy transition is not just about technology — it is about trust, timing, and transaction models. As federal uncertainty grows and climate goals face political headwinds, a new coalition of subnational actors is rising to stabilize markets, accelerate permitting, and finance a more inclusive green economy. This white paper, developed by the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) in collaboration with Climate Group and the Center for Public Enterprise (CPE), outlines a bold vision: one in which state and local governments – working hand-in-hand with mission-aligned investors and other stakeholders – lead a new wave of public-private clean energy deployment.

Drawing on insights from the closed-door session “De-Risking the Clean Energy Transition” and subsequent permitting discussions at the 2025 U.S. Leaders Forum, this paper offers strategic principles and practical pathways to scale subnational climate finance, break down permitting barriers, and protect high-potential projects from political volatility. This paper presents both a roadmap and an invitation for continued collaboration. FAS and its partners will facilitate further development and implementation of approaches and ideas described herein, with the goals of (1) directing bridge funding towards valuable and investable, yet at-risk, clean energy projects, and (2) building and demonstrating the capacity of subnational actors to drive continued growth of an equitable clean economy in the United States.

We invite government agencies, green banks and other financial institutions, philanthropic entities, project developers, and others to formally express interest in learning more and joining this work. To do so, contact Zoe Brouns (zbrouns@fas.org).

The Moment: Opportunity Meets Urgency

We are in the complex middle of a global energy transition. Clean energy and technology are growing around the world, and geopolitical competition to consolidate advantage in these sectors is intensifying. The United States has the potential to lead, but that leadership is being tested by erratic federal environmental policies and economic signals. Meanwhile, efforts to chart a lasting domestic clean energy path that resonates with the full American public have fallen short. Demand is rising — fueled by AI, electrification, and industrial onshoring – yet opposition to clean energy buildout is growing, permitting systems are gridlocked, and legacy regulatory frameworks are failing to keep up. This moment calls for new leadership rooted in local and regional capacity and needs. Subnational governments, green and infrastructure banks, and other funders have a critical opportunity to stabilize clean energy investment and sustain progress amid federal uncertainty. Thanks to underlying market trends favoring clean energy and clean technology, and to concerted efforts over the past several years to spur U.S. growth in these sectors, there is now a pipeline of clean projects across the country that are shovel-ready, relatively de-risked and developed, and investable (Box 1). Subnational actors can work together to identify these projects, and to mobilize capital and policy to sustain them in the near term.

The New York Power Authority used a simple, quick Request for Information (RFI) to identify readily investible clean energy projects in New York, and was then able to financially back many of the identified projects thanks to its strong bond rating and ability to access capital. As Paul Williams, CEO of the Center for Public Enterprise, noted, this powerful approach allowed the Authority to “essentially [pull] a 3.5-gigawatt pipeline out of thin air in less than a year.”

States, cities, and financial institutions are already beginning to provide the support and sustained leadership that federal agencies can no longer guarantee. They’re developing bond-backed financing, joint procurement schemes, rapid permitting pilot zones, and revolving loan funds — not just to fill gaps, but to reimagine what clean energy governance looks like in an era of fragmentation. One compelling example is the Connecticut Green Bank, which has successfully blended public and private capital to deploy over $2 billion in clean energy investments since its founding. Through programs like its Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE) financing and Solar for All initiative, the bank has reduced emissions, created jobs, and delivered energy savings to underserved communities.

Indeed, this kind of mission-oriented strategy – one that harnesses finance and policy towards societally beneficial outcomes, and that entrepreneurially blends public and private capacities – is in the best American tradition. Key infrastructure and permitting decisions are made at the state and local levels, after all. And state and local governments have always been central to creating and shaping markets and underwriting innovation that ultimately powers new economic engines. The upshot is clear and striking: subnational climate finance isn’t just a workaround. It may be the most politically durable and economically inclusive way to future-proof the clean energy transition.

The Role of Subnational Finance in the Clean Energy Transition

Recent years saw heavy reliance on technocratic federal rules to spur a clean energy transition. But a new political climate has forced a reevaluation of where and how federal regulation works best. While some level of regulation is important for creating certainty, demand, and market and investment structures, it is undeniable that the efficacy and durability of traditional environmental regulatory approaches has waned. There is an acute need to articulate and test new strategies for actually delivering clean energy progress (and a renewed economic paradigm for the country) in an ever-more complex society and dynamic energy landscape.

Affirmatively wedding finance with larger public goals will be a key component of this more expansive, holistic approach. Finance is a powerful tool for policymakers and others working in the public interest to shape the forward course of the green economy in a fair and effective way. In the near term, opportunities for subnational investments are ripe because the now partially paused boom in potential firms and projects generated by recent U.S. industrial policy has generated a rich set of already underwritten, due-diligenced projects for re-investment. In the longer term, the success of redesigned regulatory schema will almost certainly depend on creating profitable firms that can carry forward the energy transition. Public entities can assume an entrepreneurial role in ensuring these new economic entities, to the degree they benefit from public support, advance the public interest. Indeed, financial strategies that connect economic growth to shared prosperity will be important guardrails for an “abundance” approach to environmental policy – an approach that holds significant promise to accelerate necessary societal shifts, but also presents risk that those shifts further enrich and empower concentrated economic interests.

To be sure, subnational actors generally cannot fund at the scale of the federal government. However, they can mobilize existing revenue and debt resources, including via state green and infrastructure banks, bonding tools, and direct investment financing strategies, to seed capital for key projects and to provide a basis for larger capital stacks for key endeavors. They are also particularly well suited to provide “pre-development” support to help projects move through start-up phases and reach construction and development. Subnational entities can engage sectorally and in coalition to scale up financing, to draw in private actors, and to support projects along the whole supply and value chain (including, for instance, multi-state transmission and grid projects, multi-state freight and transportation network improvements, and multi-state industrial hubs for key technologies).

A wide range of financing strategies for clean energy projects already exist. For instance:

- Revolving loan funds can help public entities provide lower-cost debt financing to draw in additional private capital.

- Joint procurements or bundled financing can set technological standards, provide pricing power, and reduce the cost of capital for smaller businesses and make it easier for them to break into the clean energy economy.

- Financing programs for projects with public benefits can be designed in ways that allow government investors to take a small equity stake, sharing both risk and revenue over time.

Strategies like these empower states and other subnational actors to de-risk and drive the clean energy transition. The expanding green banking industry in the United States, and similar institutions globally, further augment subnational capacity. What is needed is rapid scaling and ready capitalization.

There is presently tremendous need and opportunity to deploy flexible financing strategies across projects that are shovel-ready or in progress but may need bridge funding or other investments in the wake of federal cuts. The critical path involves quickly identifying valuable, vetted projects in need of support, followed by targeted provision of financing that leverages the superior capital access of public institutions.

Projects could be identified through simple, quick Requests for Information (RFIs) like the one recently used to great effect by the New York Power Authority to build a multi-gigawatt clean energy pipeline (see Box 1, above). This model, which requires no new legislation, could be adopted by other public entities with bonding authority. Projects could also be identified through existing databases, e.g., of projects funded by, or proposed for funding under, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) or Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).

There is even the possibility of establishing a matchmaking platform that connects projects in need of financing with entities prepared to supply it. Projects could be grouped sectorally (e.g., freight or power sector projects) or by potential to address cross-cutting issues (e.g., cutting pollution burdens or managing increasing power grid load and its potential to electrify new economic areas). As economic mobilization around clean energy gains steam and familiarity with flexible financing strategies grows, such strategies can be extended to new projects in ways that are tailored to community interests, capacity, and needs.

Principles for Effective, Equitable Investment

The path outlined above is open now but will substantially narrow in the coming months without concerted, coordinated action. The following principles can help subnational actors capitalize on the moment effectively and equitably. It is worth emphasizing that equitable investment is not only a moral imperative – it is a strategic necessity for maintaining political legitimacy, ensuring community buy-in, and delivering long-term economic resilience across regions.

Funders must clearly state goals and be proactive in pursuing them – starting now to address near-term instability. Rather than waiting for projects to come to them, subnational governments, financial institutions, and other funders should use their platforms and convening power to lay out a “mission” for their investments – with goals like electrifying the industrial sector, modernizing freight terminals and ports, and accelerating transmission infrastructure with storage for renewables. Funders should then use tools like simple RFIs to actively seek out potential participants in that mission.

Public equity is a key part of the capital stack, and targeted investments are needed now. With significant federal climate investments under litigation and Congressional debates on the Inflation Reduction Act ongoing, other participants in the domestic funding ecosystem must step up. Though not all federal capital can (or should) be replaced, targeted near-term investments coupled with multi-year policy and funding roadmaps by these actors can help stabilize projects that might not otherwise proceed and provide reassurance on the long-term direction of travel.

Information is a surprisingly powerful tool. Deep, shared, information architectures and clarity on policy goals are key for institutional investors and patient capital. Shared information on costs, barriers, and rates of return would substantially help facilitate the clean energy transition – and could be gathered and released by current investors in compiled form. Sharing transparent goals, needs, and financial targets will be especially critical in the coming months. Simple RFIs targeted at businesses and developers can also function as dual-purpose information-gathering and outreach tools for these investors. By asking basic questions through these RFIs (which need not be more than a page!), investors can build the knowledge base for shaping their clean technology and energy plans while simultaneously drawing more potential participants into their investment networks.

States should invest to grow long-term businesses. The clean energy transition can only be self-sustaining if it is profitable and generates firms that can stand on their own. Designing state incentive and investment projects for long-term business growth, and aligning complementary policy, is critical – including by designing incentive programs to partner well with other financing tools, and to produce long-term affordability and deployment gains, especially for entities which may otherwise lack capital access. State strategies, like the one New Mexico recently published, that outline energy-transition and economic plans and timelines are crucial to build certainty and align action across the investment and development ecosystem. Metrics for green programs should assess prospects for long-term business sustainability as well as tons of emissions reduced.

States can finance the clean energy transition while securing long-term returns and other benefits. Many clean technology projects may have higher upfront costs balanced by long-term savings. Debt equity, provided through revolving loan funds, can play a large role in accelerating deployment of these technologies by buying down entry costs and paying back the public investor over time. Moreover, the superior bond ratings of state institutions substantially reduce borrowing costs; sharing these benefits is an important role for public finance. State financial institutions can explore taking equity stakes in some projects they fund that provide substantial public benefits (e.g., mega-charging stations, large-scale battery storage, etc.) and securing a rate of return over time in exchange for buying down upfront risk. Diversified subnational institutions can use cash flows from higher-return portions of their portfolios to de-risk lower-return or higher-risk projects that are ultimately in the public interest. Finally, states with operating carbon market programs can consider expanding their funding abilities by bonding against some portion of carbon market revenues, converting immediate returns to long-term collateral for the green economy.

Financing policy can be usefully combined with procurement policy. As electrification reaches individual communities and smaller businesses, many face capital-access problems. Subnational actors should consider packaging similar businesses together to provide financing for multiple projects at once, and can also consider complementary public procurement policies to pull forward market demand for projects and products (Box 2).

Explore contract mechanisms to protect public benefits. Distributive equity is as important as large-scale investment to ensure a durable economic transition. The Biden-Harris Administration substantially conditioned some investments on the existence of binding community benefit plans to ensure that project benefits were broadly shared and possible harms to communities mitigated. Subnational investors could develop parallel contractual agreements. There may also be potential to use contracts to enable revenue sharing between private and public institutions, partially addressing any impacts of changes to the IRA’s current elective pay and transferability provisions by shifting realized income to the public entities that currently use those programs from the private entities that realize revenue from projects.

Joint procurements, whereby two or more purchasers enter into a single contract with a vendor, can bring down prices of emerging clean technologies by increasing purchase volume, and can streamline technology acquisition by sharing contracting workload across partners. Joint procurement and other innovative procurement policies have been used successfully to drive deployment of zero-emission buses in Europe and, more recently, the United States. Procurement strategies can be coupled with public financing. For instance, the Federal Transit Agency’s Low or No Emission Grant Program for clean buses preferences applications that utilize joint procurement, thereby helping public grant dollars go further.

The rising importance of the electrical grid across sectors creates new financial product opportunities. As the economy decarbonizes, more previously independent sectors are being linked to the electric grid, with load increasing (AI developments exacerbate this trend). That means that project developers in the green economy can offer a broader set of services, such as providing battery storage for renewables at vehicle charging points, distributed generation of power to supply new demand, and potential access to utility rate-making. Financial institutions should closely track rate-making and grid policy and explore avenues to accelerate beneficial electrification. There is a surprising but potent opportunity to market and finance clean energy and grid upgrades as a national security imperative, in response to the growing threat of foreign cyberattacks that are exploiting “seams” in fragile legacy energy systems.

Global markets can provide ballast against domestic volatility. The United States has an innovative financial services sector. Even though federal institutions may retreat from clean energy finance globally over the next few years, there remains a substantial opportunity for U.S. companies to provide financing and investment to projects globally, generate trade credit, and to bring some of those revenues back into the U.S. economy.

Financial products and strategies for adaptation and resilience must not be overlooked. Growing climate-linked disasters, and associated adaptation costs, impose substantial revenue burdens on state and local governments as well as on insurers and businesses. Competition for funds between adaptation and mitigation (not to mention other government services) may increase with proposed federal cuts. Financial institutions that design products that reduce risk and strengthen resilience (e.g., by helping relocate or strengthen vulnerable buildings and infrastructure) can help reduce these revenue competitions and provide long-term benefits by tapping into the $1.4 trillion market for adaptation and resilience solutions. Improved cost-benefit estimates and valuation frameworks for these interacting systems are critical priorities.

Conclusion: A Defining Window for Subnational Leadership

Leaders from across the country agree: clean energy and clean technology are investable, profitable, and vital to community prosperity. And there is a compelling lane for innovative subnational finance as not just a stopgap or replacement for federal action, but as a central area of policy in its own right.

The federal regulatory state is, increasingly, just a component of a larger economic transition that subnational actors can help drive, and shape for public benefit. Designing financial strategies for the United States to deftly navigate that transition can buffer against regulatory uncertainty and create a conducive environment for improved regulatory designs going forward. Immediate responses to stabilize climate finance, moreover, can build a foundation for a more engaged, and innovative, coalition of subnational financial actors working jointly for the public good.

Active state and private planning is the key to moving down these paths, with governments setting a clear direction of travel and marshaling their convening powers, capital access, and complementary policy tools to rapidly stabilize key projects and de-risk future capital choices.

There is much to do and no time to lose as governments and investors across the country seek to maintain clean technology progress. The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) and its partners will facilitate further development and implementation of approaches and ideas described above, with the goals of (1) directing bridge funding towards valuable and investable, yet at-risk, clean energy projects, and (2) building and demonstrating the capacity of subnational actors to drive continued growth of an equitable clean economy in the United States.

We invite government agencies, green banks and other financial institutions, philanthropic entities, project developers, and others to formally express interest in learning more and joining this work. To do so, contact Zoe Brouns (zbrouns@fas.org).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the many partners who contributed to this report, including: Dr. Jedidah Isler and Zoë Brouns at the Federation of American Scientists, Sydney Snow at Climate Group, Yakov Feigin, Chirag Lala, and Advait Arun at the Center for Public Enterprise, and Jayni Hein at Covington and Burling LLP.

Federal Climate Policy Is Being Gutted. What Does That Say About How Well It Was Working?

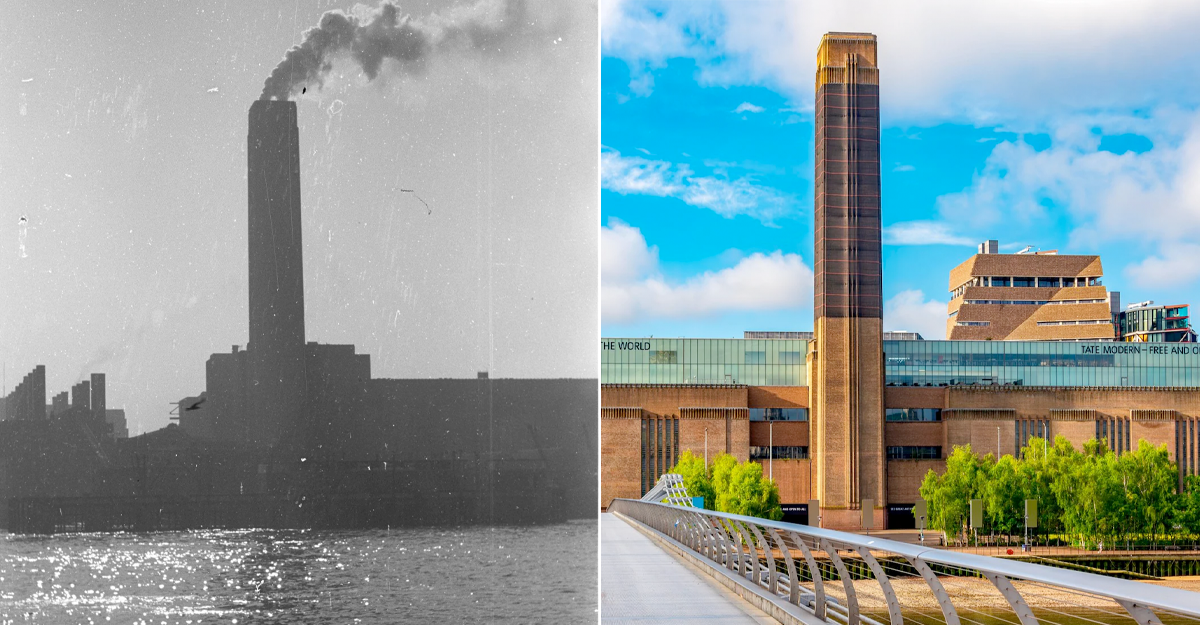

On the left is the Bankside Power Station in 1953. That vast relic of the fossil era once towered over London, oily smoke pouring from its towering chimney. These days, Bankside looks like the right:

The old power plant’s vast turbine hall is now at the heart of the airy Tate Modern Art Museum; sculptures rest where the boilers once churned.

Bankside’s evolution into the Tate illustrates that transformations, both literal and figurative, are possible for our energy and economic systems. Some degree of demolition – if paired with a plan – can open up space for something innovative and durable.

Today, the entire energy sector is undergoing a massive transformation. After years of flat energy demand served by aging fossil power plants, solar energy and battery storage are increasingly dominating energy additions to meet rising load. Global investment in clean energy will be twice as big as investment in fossil fuels this year. But in the United States, the energy sector is also undergoing substantial regulatory demolition, courtesy of a wave of executive and Congressional attacks and sweeping potential cuts to tax credits for clean energy.

What’s missing is a compelling plan for the future. The plan certainly shouldn’t be to cede leadership on modern energy technologies to China, as President Trump seems to be suggesting; that approach is geopolitically unwise and, frankly, economically idiotic. But neither should the plan be to just re-erect the systems that are being torn down. Those systems, in many ways, weren’t working. We need a new plan – a new paradigm – for the next era of climate and clean energy progress in the United States.

Asking Good Questions About Climate Policy Designs

How do we turn demolition into a superior remodel? First, we have to agree on what we’re trying to build. Let’s start with what should be three unobjectionable principles.

Principle 1. Climate change is a problem worth fixing – fast. Climate change is staggeringly expensive. Climate change also wrecks entire cities, takes lives, and generally makes people more miserable. Climate change, in short, is a problem we must fix. Ignoring and defunding climate science is not going to make it go away.

Principle 2. What we do should work. Tackling the climate crisis isn’t just about cleaning up smokestacks or sewer outflows; it’s about shifting a national economic system and physical infrastructure that has been rooted in fossil fuels for more than a century. Our responses must reflect this reality. To the extent possible, we will be much better served by developing fit-for-purpose solutions rather than just press-ganging old institutions, statutes, and technologies into climate service.

Principle 3. What we do should last. The half-life of many climate strategies in the United States has been woefully short. The Clean Power Plan, much touted by President Obama, never went into force. The Trump administration has now turned off California’s clean vehicle programs multiple times. Much of this hyperpolarized back-and-forth is driven by a combination of far-right opposition to regulation as a matter of principle and the fossil fuel industry pushing mass de-regulation for self-enrichment – a frustrating reality, but one that can only be altered by new strategies that are potent enough to displace vocal political constituencies and entrenched legacy corporate interests.

With these principles in mind, the path forward becomes clearer. We can agree that ambitious climate policy is necessary; protecting Americans from climate threats and destabilization (Principle 1) directly aligns with the founding Constitutional objectives of ensuring domestic tranquility, providing for the common defense, and promoting general welfare. We can also agree that the problem in front of us is figuring out which tools we need, not how to retain the tools we had, regardless of their demonstrated efficacy (Principle 2). And we can recognize that achieving progress in the long run requires solutions that are both politically and economically durable (Principle 3).

Below, we consider how these principles might guide our responses to this summer’s crop of regulatory reversals and proposed shifts in federal investment.

Honing Regulatory Approaches

The Trump Administration recently announced that it plans to dismantle the “endangerment finding” – the legal predicate for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants and transportation; meanwhile, the Senate revoked permission for California to enforce key car and truck emission standards. It has also proposed to roll back key power plant toxic and greenhouse gas standards. We agree with those who think that these actions are scientifically baseless and likely illegal, and therefore support efforts to counter them. But we should also reckon honestly with how the regulatory tools we are defending have played out so far.

Federal and state pollution rules have indisputably been a giant public-health victory. EPA standards under the Clean Air Act led directly to dramatic reductions in harmful particulate matter and other air pollutants, saving hundreds of thousands of lives and avoiding millions of cases of asthma and other respiratory diseases. Federal regulations similarly caused mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants to drop by 90% in just over a decade. Pending federal rollbacks of mercury rules thus warrant vocal opposition. In the transportation sector, tailpipe emissions standards for traditional combustion vehicles have been impressively effective. These and other rules have indeed delivered some climate benefits by forcing the fossil fuel industry to face pollution clean-up costs and driving development of clean technologies.

But if our primary goal is motivating a broad energy transition (i.e., what needs to happen per Principle 1), then we should think beyond pollution rules as our only tools – and allocate resources beyond immediate defensive fights. Why? The first reason is that, as we have previously written, these rules are poorly equipped to drive that transition. Federal and state environmental agencies can do many things well, but running national economic strategy and industrial policy primarily through pollution statutes is hardly the obvious choice (Principle 2).

Consider the power sector. The most promising path to decarbonize the grid is actually speeding up replacement of old coal and gas plants with renewables by easing unduly complex interconnection processes that would speed adding clean energy to address rising demand, and allow the old plants to retire and be replaced – not bolting pollution-control devices on ancient smokestacks. That’s an economic and grid policy puzzle, not a pollution regulatory challenge, at heart. Most new power plants are renewable- or battery-powered anyway. Some new gas plants might be built in response to growing demand, but the gas turbine pipeline is backed up, limiting the scope of new fossil power, and cheaper clean power is coming online much more quickly wherever grid regulators have their act together. Certainly regulations could help accelerate this shift, but the evidence suggests that they may be complementary, not primary, tools.

The upshot is that economics and subnational policies, not federal greenhouse gas regulation, have largely driven power plant decarbonization to date and therefore warrant our central focus. Indeed, states that have made adding renewable infrastructure easy, like Texas, have often been ahead of states, like California, where regulatory targets are stronger but infrastructure is harder to build. (It’s also worth noting that these same economics mean that the Trump Administration’s efforts to revert back to a wholly fossil fuel economy by repealing federal pollution standards will largely fail – again, wrong tool to substantially change energy trajectories.)

The second reason is that applying pollution rules to climate challenges has hardly been a lasting strategy (Principle 3). Despite nearly two decades of trying, no regulations for carbon emissions from existing power plants have ever been implemented. It turns out to be very hard, especially with the rise of conservative judiciaries, to write legal regulations for power plants under the Clean Air Act that both stand up in Court and actually yield substantial emissions reductions.

In transportation, pioneering electric vehicle (EV) standards from California – helped along by top-down economic leverage applied by the Obama administration – did indeed begin a significant shift and start winning market share for new electric car and truck companies; under the Biden administration, California doubled down with a new set of standards intended to ultimately phase out all sales of gas-powered cars while the EPA issued tailpipe emissions standards that put the industry on course to achieve at least 50% EV sales by 2030. But California’s EV standards have now been rolled back by the Trump administration and a GOP-controlled Congress multiple times; the same is true for the EPA rules. Lest we think that the Republican party is the sole obstacle to a climate-focused regulatory regime that lasts in the auto sector, it is worth noting that Democratic states led the way on rollbacks. Maryland, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Vermont all paused, delayed, or otherwise fuzzed up their plans to deploy some of their EV rules before Congress acted against California. The upshot is that environmental standards, on their own, cannot politically sustain an economic transition at this scale without significant complementary policies.

Now, we certainly shouldn’t abandon pollution rules – they deliver massive health and environmental benefits, while forcing the market to more accurately account for the costs of polluting technologies, But environmental statutes built primarily to reduce smokestack and tailpipe emissions remain important but are simply not designed to be the primary driver of wholesale economic and industrial change. Unsurprisingly, efforts to make them do that anyway have not gone particularly well – so much so that, today, greenhouse gas pollution standards for most economic sectors either do not exist, or have run into implementation barriers. These observations should guide us to double down on the policies that improve the economics of clean energy and clean technology — from financial incentives to reforms that make it easier to build — while developing new regulatory frameworks that avoid the pitfalls of the existing Clean Air Act playbook. For example, we might learn from state regulations like clean electricity standards that have driven deployment and largely withstood political swings.

To mildly belabor the point – pollution standards form part of the scaffolding needed to make climate progress, but they don’t look like the load-bearing center of it.

Refocusing Industrial Policy

Our plan for the future demands fresh thinking on industrial policy as well as regulatory design. Years ago, Nobel laureate Dr. Elinor Ostrom pointed out that economic systems shift not as a result of centralized fiat, from the White House or elsewhere, but from a “polycentric” set of decisions rippling out from every level of government and firm. That proposition has been amply borne out in the clean energy space by waves of technology innovation, often anchored by state and local procurement, regional technology clusters, and pioneering financial institutions like green banks.

The Biden Administration responded to these emerging understandings with the CHIPS and Science Act, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) – a package of legislation intended to shore up U.S. leadership in clean technology through investments that cut across sectors and geographies. These bills included many provisions and programs with top-down designs, but the package as a whole but did engage with, and encourage, polycentric and deep change.

Here again, taking a serious look at how this package played out can help us understand what industrial policies are most likely to work (Principle 2) and to last (Principle 3) moving forward.

We might begin by asking which domestic clean-technology industries need long-term support and which do not in light of (i) the multi-layered and polycentric structure of our economy, and (ii) the state of play in individual economic sectors and firms at the subnational level. IRA revisions that appropriately phase down support for mature technologies in a given sector or region where deployment is sufficient to cut emissions at an adequate pace could be worth exploring in this light – but only if market-distorting supports for fossil-fuel incumbents are also removed. We appreciate thoughtful reform proposals that have been put forward by those on the left and right.

More directly: If the United States wants to phase down, say, clean power tax credits, such changes should properly be phased with removals of support for fossil power plants and interconnection barriers, shifting the entire energy market towards a fair competition to meet increasing load, as well as new durable regulatory structures that ensure a transition to a low-carbon economy at a sufficient pace. Subsidies and other incentives could appropriately be retained for technologies (e.g., advanced battery storage and nuclear) that are still in relatively early stages and/or for which there is a particularly compelling argument for strengthening U.S. leadership. One could similarly imagine a gradual shift away from EV tax credits – if other transportation system spending was also reallocated to properly balance support among highways, EV charging stations, transit, and other types of transportation infrastructure. In short, economic tools have tremendous power to drive climate progress, but must be paired with the systemic reforms needed to ensure that clean energy technologies have a fair pathway to achieving long-term economic durability.

Our analysis can also touch on geopolitical strategy. It is true that U.S. competitors are ahead in many clean technology fields; it is simultaneously true that the United States has a massive industrial and research base that can pivot ably with support. A pure on-shoring approach is likely to be unwise – and we have just seen courts enjoin the administration’s fiat tariff policy that sought that result. That’s a good opportunity to have a more thoughtful conversation (in which many are already engaging) on areas where tariffs, public subsidies, and other on-shoring planning can actually position our nation for long-term economic competition on clean technology. Opportunities that rise to the top include advanced manufacturing, such as for batteries, and critical industries, like the auto sector. There is also a surprising but potent national security imperative to center clean energy infrastructure in U.S. industrial policy, given the growing threat of foreign cyberattacks that are exploiting “seams” in fragile legacy energy systems.

Finally, our analysis suggests that states, which are primarily responsible for economic policy in their jurisdictions, have a role to play in this polycentric strategy that extends beyond simply replicating repealed federal regulations. States have a real opportunity in this moment to wed regulatory initiatives with creative whole-of-the-economy approaches that can actually deliver change and clean economic diversification, positioning them well to outlast this period of churn and prosper in a global clean energy transition.

A successful and “sticky” modern industrial policy must weave together all of the above considerations – it must be intentionally engineered to achieve economic and political durability through polycentric change, rather than relying solely or predominantly on large public subsidies.

Conclusion

The Trump Administration has moved with alarming speed to demolish programs, regulations, and institutions that were intended to make our communities and planet more liveable. Such wholesale demolition is unwarranted, unwise, and should not proceed unchecked. At the same time, it is, as ever, crucial to plan for the future. There is broad agreement that achieving an effective, equitable, and ethical energy transition requires us to do something different. Yet there are few transpartisan efforts to boldly reimagine regulatory and economic paradigms. Of course, we are not naive: political gridlock, entrenched special interests, and institutional inertia are formidable obstacles to overcome. But there is still room, and need, to try – and effort bears better fruit when aimed at the right problems. We can begin by seriously debating which past approaches work, which need to be improved, which ultimately need imaginative recasting to succeed in our ever-more complex world. Answers may be unexpected. After all, who would have thought that the ultimate best future of the vast oil-fired power station south of the Thames with which we began this essay would, a few decades later, be a serene and silent hall full of light and reflection?

Updating the Clean Electricity Playbook: Learning Lessons from the 100% Clean Agenda

Building clean energy faster is the most significant near-term strategy to combat climate change. While the Biden Administration and the advocacy community made significant gains to this end over the past few years, we failed to secure major pieces of the policy agenda, and the pieces we did secure are not resulting in as much progress as projected. As a result, clean energy deployment is lagging behind levels needed to match modeled cost-effective scenarios, let alone to achieve the Paris climate goals. Simultaneously, the Trump Administration is actively dismantling the foundations that have underpinned our existing policy playbook.

Adjusting course to rapidly transform the electricity sector—to cut pollution, reduce costs, and power a changing economy—requires us to upgrade the regulatory frameworks we rely upon, the policy tools we prioritize, and the coalition-building and messaging strategies we use.

After leaving the Biden Administration, I joined FAS as a Senior Fellow to jump into this work. We plan to assess the lessons from the Biden era electricity sector plan, interrogate what is and is not working from the advocacy community’s toolkit, and articulate a new vision for policy and strategy that is durable and effective, while meeting the needs of our modern society. We need a new playbook that starts in the states and builds toward a national mission that can tackle today’s pressing challenges and withstand today’s turbulent politics. And we believe that this work must be transpartisan—we intend to draw from efforts underway in a wide range of local political contexts to build a strategy that appeals to people with diverse political views and levels of political engagement.

This project is part of a larger FAS initiative to reimagine the U.S. environmental regulatory state and build a new system that can address our most pressing challenges.

Betting Big on 100% Clean Electricity

If we are successful in fighting the climate crisis, the largest share of domestic greenhouse gas emissions reductions over the next ten years will come from building massive amounts of new clean energy and in turn reducing pollution from coal- and gas-fired power plants. Electricity will also need to be cheap, clean, and abundant to move away from gasoline vehicles, natural gas appliances in homes, and fossil fuel-fired factories toward clean electric alternatives.

That’s why clean electricity has been the centerpiece of federal and state climate policy. The signature climate initiative of the Obama Administration was the Clean Power Plan. Over the past several decades, states have made the most emissions progress through renewable portfolio standards and clean electricity standards that require power companies to provide increasing amounts of clean electricity. Now 24 (red and blue) states and D.C. have goals or requirements to achieve 100 percent clean electricity. And in the 2020 election, Democratic primary candidates competed over how ambitious their plans were to transform the electricity grid and deploy clean energy.

As a result of that competition and the climate movement’s efforts to put electricity at the center of the strategy, President Biden campaigned on achieving 100 percent clean electricity by 2035. This commitment was very ambitious—it surpassed every state goal except Vermont’s, Rhode Island’s, and D.C.’s. In making such a bold commitment, Biden recognized how essential the power sector is to addressing the climate crisis. He also staked a bet that the right policies—large incentives for companies, worker protections, and support for a diverse mix of low-carbon technologies—would bring together a coalition that would fight for the legislation and regulations needed to make the 2035 goal a reality.

A Mix of Wins and Losses

That bet only partially paid off. We won components of the agenda that made major strides toward 100% clean electricity. New tax credits are accelerating deployment of wind, solar, and battery storage (although the Trump Administration and Republicans in Congress are actively working to repeal these credits). Infrastructure investments are driving grid upgrades to accommodate additional clean energy. And new grant programs and procurement policies are speeding up commercialization of critical technologies such as offshore wind, advanced nuclear, and enhanced geothermal.

But the movement failed to secure the parts of the plan that would have ensured an adequate pace of deployment and pollution reductions, including a federal clean electricity standard, a suite of durable emissions regulations to cover the full sector, and federal and state policies to reduce roadblocks to new infrastructure and align utility incentives with clean energy deployment. We ran into real-world and political headwinds that held us back. For example, deployment was stifled by long timelines to connect projects to the grid and local ordinances and siting practices that block clean energy. Policy initiatives were thwarted by political opposition from perceived reliability impacts and blowback from increasing electricity rates, especially for newer technologies like offshore wind and advanced nuclear. The opposition to clean energy successfully weaponized the rising cost of living to fight climate policies, even where clean energy would make life less expensive. These barriers not only impeded commercialization and deployment but also dampened support from key stakeholders (project developers, utilities, grid operators, and state and local leaders) for more ambitious policies. The necessary coalitions did not come together to support and defend the full agenda.

As a result, we are building clean energy much too slowly. In 2024, the United States built nearly 50 gigawatts of new clean power. This number, while a new record, falls short of the amount needed to address the climate crisis. Analysis from three leading research projects found that, with the tax incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act, the future in which we get within striking distance of the Paris climate goals requires 70 to 125 gigawatts of new clean power per year for the next five years, 40 to 250 percent higher than our record annual buildout.

Where do we go from here?

The climate crisis demands faster and deeper policy change with more staying power. Addressing the obvious obstacles standing in the way of clean energy deployment, like the process to connect power plants to the grid, is necessary but insufficient. We must also develop new policy frameworks and expanded coalitions to facilitate the rapid transformation of the electricity system.

This work requires us to ask and creatively answer an evolving set of questions, including: What processes are holding us back from faster buildout, and how do we address them? How can utility incentives be better aligned with the deployment and infrastructure investment we need and support for the required policies? How can the way we pay for electricity be better designed to protect customers and a livable climate? Where have our coalitional strategies failed to win the policies we need, and how do we adjust? How should we talk about these problems and the solutions to build greater support?

We must develop answers to these questions in a way that leads us to more transformative, lasting policies. We believe that, in the near term, much of this work must happen at the state level, where there is energy to test out new ideas and frameworks and iterate on them. We plan to build out a state-level playbook that is actionable, dynamic, and replicable. And we intend to learn from the experiences of states and municipalities with diverse political contexts to develop solutions that address the concerns of a wide range of audiences.

We cannot do this work on our own. We plan to draw on the expertise of a diverse range of organizations and people who have been working on these problems from many vantage points. If you are working on these issues and are interested, please join us in collaboration and conversation by reaching out to akrishnaswami@fas.org.

Building an Environmental Regulatory System that Delivers for America

The Clean Air Act. The Clean Water Act. The National Environmental Policy Act. These and most of our nation’s other foundational environmental laws were passed decades ago – and they have started to show their age. The Clean Air Act, for instance, was written to cut air pollution, not to drive the whole-of-economy response that the climate crisis now warrants. The Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 was designed to make cars more efficient in a pre-electric vehicle era, and now puts the Department of Transportation in the awkward position of setting fuel economy standards in an era when more and more cars don’t burn gas.