If We’ve Learned Anything It is that Learning Agendas Bring Evidence into Policymaking

As a public health and policy professional, I often think about how scientific evidence makes its way into policymaking, and how that policy impacts the everyday lives of all Americans. Evidence-based policymaking is not just about policy that draws on science, it’s about how decisions are made, evaluated, and improved over time. For example, peer-reviewed studies showing the benefits of vaccination informed Operation Warp Speed and that the use of fluoride in water promotes public health for Americans because fluoride prevents the spread of diseases. It’s in our best interest that our government makes decisions using an evidence-based approach because of the outsized impacts these policies can have on our lives.

This is one of the main reasons The Foundations for Evidence-Based Policy Making Act of 2018, better known as the Evidence Act, was signed into law on January 14, 2019. This Act aims to increase the government’s capacity to use data and evidence to drive decision-making and policy development. One of its core components is a mandate that the 24 Chief Financial Officer (CFO) federal agencies appoint Evaluation Officers and Chief Data Officers. These officers have the legal standing to implement and enforce participatory data-driven policymaking within the federal government, and one of their key responsibilities is to oversee the development of agency learning agendas.

Learning agendas are a set of high-priority questions developed by an agency with input from external stakeholders to assess the effectiveness of their programs and policies. These multi-year agendas are intended to be a crucial component of evidence-based policymaking and they require recurring engagement with non-governmental experts as part of the planning and evaluation cycle. These agendas should shape how policies, regulations, and programs impact the communities they serve. Answers to these learning agenda questions are also intended to inform critical budget decisions, allowing agencies to ensure that federal funding is spent appropriately.

Why use learning agendas?

There are several integral parts of learning agendas that make them a solid course of action for evidence-based policymaking. This process generates targeted evidence needed for crucial decisions, and in turn, that evidence supports more informed decision-making and strategic resource allocation. Taxpayers benefit from this approach because data illuminates which programs and policies are not efficient and should be eliminated.

- Learning agendas help facilitate evidence-based policymaking by using data to identify knowledge gaps.

- Learning agendas require internal and external stakeholder engagement which ensures the inclusion of diverse perspectives that represent various communities.

- Learning agendas help agencies prioritize critical questions and areas of concern where research and data are needed, while also allowing them to allocate resources appropriately based on needs.

- Lastly, learning agendas encourage transparency and accountability to the American public through clearly outlining their research questions and plans, which emboldens the public to “conduct oversight”. This leads to true accountability because the public has access to the information that will be used to make decisions on their behalf.

State and Local Governments Use of Learning Agendas

While learning agendas have primarily been used by the federal government, they are increasingly relevant to state and local governments as well. These governments are responsible for delivering services that directly impact the day-to-day lives of most people when thinking about public health, education, housing, and more. By using learning agendas, state and local governments can test new policies and interventions, make adjustments as needed, and create opportunities for greater innovation. For example, North Carolina’s Office of Strategic Partnerships facilitated the development of a learning agenda for the state’s Department of Public Safety; this in turn allowed department leaders to establish partnerships with universities, receive quick turnaround answers, and determine what adjustments to make to their programming in the near term. Implementing learning agendas at the state and local levels will provide more structure to help identify areas for improvement, gather evidence, and support informed decision-making about what works for their communities. Additionally, insights gained from learning agendas can assist in scaling innovation through small pilot programs, guiding the strategic allocation of funds, and help build credibility and public trust.

What is the status of learning agendas in the current administration?

Learning agendas are still in the early stages of implementation across federal agencies, and notably, these efforts have not been supported by dedicated funding. This first set, applicable from FY2022-26, was released in 2022. As of now, agencies continue to implement these learning agendas, although there have been some challenges in fully realizing their intended impact. The new guidance under the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-11 requires updates and revisions to these agendas, with a new focus on making them actionable and measurable through evidence plans. To clarify, the initial FY2022-26 learning agendas are evolving as part of an updated strategy to ensure that federal agencies are better equipped to use data and evidence in policymaking. Agencies are required to submit updated evidence plans as part of their annual planning cycle. These revisions provide an opportunity for reflection on the lessons learned and for further integration of evidence-building practices in the decision-making processes. These formative years have generated important momentum, which has established a foundation for using learning agendas as practical tools. To ensure that their impact is lasting, it is critical to sustain and build on this early progress so that learning agendas evolve from what has so far been mostly a compliance exercise into a standard mechanism for guiding investments, policy, and program improvements at all levels of government. The goal is to ensure that learning agendas are meaningful and actionable in a way that informs agencies of how to prioritize and evaluate their work.

Under the new Administration, changes were made to the guidance that governs the learning agenda process. This updated guidance no longer emphasizes periodic updates for all learning agendas. In recent Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Guidance from OMB Circular A-11 Section 290, the development of learning agendas and evaluation plans will be consolidated into an annually updated evidence plan. Differing from the previous approach, the new evidence plan requires agencies to be specific when providing information about their sources of data, research methods, timelines, and how the findings will be used by each agency for decision-making. For evaluation purposes, all agencies must clearly define their evaluation questions and specify the information they plan to collect. This change is an effort to create a more streamlined and actionable roadmap for agencies by making them more focused and transparent. With this new requirement requiring more clarity around methods, data sources, and cases, the new evidence plan approach may have the ability to ensure better accountability. This level of precision moves the process beyond compliance and toward a model that supports continuous learning and data-informed policymaking.

If we want to continue the momentum of increasing public trust, transparency, and delivering results to the American people, it’s abundantly clear that we must continue to rely on evidence for all policy decision making. Despite changes in the approach, the mandate for evidence-based policymaking remains strong, and learning agendas are crucial for maintaining public trust in government actions. Federal agencies now have an opportunity to learn from successes and challenges faced in the implementation of their first set of learning agendas, creating new versions for the upcoming fiscal year that are more useful and actionable for decision-making. However, it’s critical that we no longer view learning agendas as merely compliance exercises, but as tools that inform better policies and programs, ultimately benefiting the American people.

While it seems that the current political climate can at times present challenges to the use of evidence-based data sources for decision making, those of us who are passionate about ensuring results for the American people will continue to firmly stand on the belief that learning agendas are a crucial component to successfully navigate a changing future. The new Evidence Plans that agencies are developing provide an important opportunity to ensure that evidence-based decision-making continues to evolve. This is a pivotal moment for agencies to build on prior efforts and enhance the strategic value of their plans, ensuring they are more impactful and better aligned with long-term evidence-building priorities. This is a moment for agencies to deliver more robust, data-driven solutions for the American public.

Call to Action

The purpose of learning agendas is to aid in making better policy decisions. However, we’re now seeing tools that were once used to collect evidence-based and scientific data being dismantled at alarming rates. There have been countless agency firings, extreme funding cuts for programs that support evidence-based work, and attempts to censor those who wish to continue reporting data on systems that are now considered not aligned with the agenda of the current administration. This alone has made it more difficult to continue developing learning agendas which should be used as a tool to build greater efficiency.

Here’s my call to action for you. Learning agendas are statutorily mandated by the Evidence Act of 2018 and are one legal pathway to push the government to not only collect and use evidence, but also engage experts and the public in policy making. Over the next 6 to 12 months, agencies are expected to develop their updated evidence plans to align with fiscal year cycles and new requirements outlined by OMB. This makes the current moment critical for offering support, shaping priorities, and ensuring these plans reflect real evidence needs. External organizations, academic institutions, and researchers are able and willing to assist the federal government with getting answers to these priority questions that are needed to make policy decisions. Over the past year, FAS embarked on a pilot aimed at assisting federal agencies with learning agenda questions. In partnership with Cornell University’s School of Public Health, we launched an initiative to support the federal government in addressing key questions outlined in their learning agendas. Recognizing that agencies often face resource and capacity constraints in conducting timely, evidence-based research, this effort sought to bridge the gap by tapping into academic expertise. By leveraging the skills and knowledge of graduate students, we created a pathway for rigorous, policy-relevant research to be produced in direct response to agency needs. Graduate students benefit from real-world experience, while agencies receive well-informed insights that can inform policy, program design, and implementation. This mutually beneficial model not only strengthens the pipeline between academia and government, but also accelerates the use of data and evidence in public sector decision-making.

Here are a couple of ways to advance learning agendas outside of government:

- Consider partnering with policy and advocacy organizations that have convening power and a footing in the policy space to advocate for the continued use of learning agendas to improve how evidence is used in policymaking. By joining forces with organizations already familiar with the benefits of learning agendas, you can start or strengthen similar efforts in your organization. Learning agendas as a tool are still new to many, so finding ways to explore their use will also demonstrate their value.

- Second, as researchers, academic institutions, and non-profits you can offer your expertise to state/local and federal governments to help design, evaluate, or solve priority questions.

- Third, find ways in which you can educate policymakers through resources such as op-eds, policy memos, and other resources. You can co-create these materials with organizations such as FAS or identify other organizations with similar interests in advancing evidence-based policy ideas. You also have the option of scheduling a meeting with Congressional representatives to share your concerns and provide them with stories that demonstrate how learning agendas have helped the government run more efficiently.

- Fourth, educate yourself on what individual government agency learning agendas already exist, and the mandate itself. Informed citizens are crucial to democracy at all levels of government. Learning agendas can be applied at all levels, too.

- For example, in the GSA FY 2022-2026 learning agenda, one of the questions asks, “What strategies and technologies are most effective to efficiently operate and maintain Federal facilities and reduce adverse climate impacts?”. These are the kinds of concrete, priority questions that help show where gaps exist.

If you care about transparency and accountability within the federal, state and local government or if increasing public trust with the government is important to you, let’s work together. Here at FAS, we can collaborate through our policy entrepreneurship model on our Day One team to advocate for the continued development of learning agendas that are visible, actionable, and key to informed policymaking. Let’s continue to stay informed, advocate for the use of learning agendas, and support experts and other individuals who are willing to provide their expertise and research knowledge in an effort to lend factual evidence to decision makers.

For more on how the federal evidence ecosystem has evolved, read our blog post on What’s Next for Federal Evidence-Based Policymaking.

Clean Water: Protecting New York State Private Wells from PFAS

This memo responds to a policy need at the state level that originates due to a lack of relevant federal data. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has a learning agenda question that asks,“To what extent does EPA have ready access to data to measure drinking water compliance reliably and accurately?” This memo fills that need because EPA doesn’t measure private wells.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are widely distributed in the environment, in many cases including the contamination of private water wells. Given their links to numerous serious health consequences, initiatives to mitigate PFAS exposure among New York State (NYS) residents reliant on private wells were included among the priorities outlined in the annual State of the State address and have been proposed in state legislation. We therefore performed a scenario analysis exploring the impacts and costs of a statewide program testing private wells for PFAS and reimbursing the installation of point of entry treatment (POET) filtration systems where exceedances occur.

Challenge and Opportunity

Why care about PFAS?

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a class of chemicals containing millions of individual compounds, are of grave concern due to their association with numerous serious health consequences. A 2022 consensus study report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine categorized various PFAS-related health outcomes based on critical appraisal of existing evidence from prior studies; this committee of experts concluded that there is high confidence of an association between PFAS exposure and (1) decreased antibody response (a key aspect of immune function, including response to vaccines) (2) dyslipidemia (abnormal fat levels in one’s blood), (3) decreased fetal and infant growth, and (4) kidney cancer, and moderate confidence of an association between PFAS exposure and (1) breast cancer, (2) liver enzyme alterations, (3) pregnancy-induced high blood pressure, (4) thyroid disease, and (5) ulcerative colitis (an autoimmune inflammatory bowel disease).

Extensive industrial use has rendered these contaminants virtually ubiquitous in both the environment and humans, with greater than 95% of the U.S. general population having detectable PFAS in their blood. PFAS take years to be eliminated from the human body once exposure has occurred, earning their nickname as “forever chemicals.”

Why focus on private drinking water?

Drinking water is a common source of exposure.

Drinking water is a primary pathway of human exposure. Combining both public and private systems, it is estimated that approximately 45% of U.S. drinking water sources contain at least one PFAS. Rates specific to private water supplies have varied depending on location and thresholds used. Sampling in Wisconsin revealed that 71% of private wells contained at least one PFAS and 4% contained levels of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), two common PFAS compounds, exceeding Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) of 4 ng/L. Sampling in New Hampshire, meanwhile, found that 39% of private wells exceeded the state’s Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQS), which were established in 2019 and range from 11-18 ng/L depending on the specific PFAS compound. Notably, while the EPA MCLs represent legally enforceable levels accounting for the feasibility of remediation, the agency has also released health-based, non-enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) of zero for PFOA and PFOS.

PFAS in private water are unregulated and expensive to remediate.

In New York State (NYS), nearly one million households rely on private wells for drinking water; despite this, there are currently no standardized well testing procedures and effective well water treatment is unaffordable to many New Yorkers. As of April 2024, the EPA has established federal MCLs for several specific PFAS compounds and mixtures of compounds and its National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) require public water systems to begin monitoring and publicly reporting levels of these PFAS by 2027; if monitoring reveals exceedances of the MCLs, public water systems must also implement solutions to reduce PFAS by 2029. In contrast, there are no standardized testing procedures or enforceable limits for PFAS in private water. Additionally, testing and remediating private wells are both associated with high costs which are unaffordable to many well owners; prices range in hundreds of dollars for PFAS testing and can cost several thousands of dollars for the installation and maintenance of effective filtration systems.

How are states responding to the problem of PFAS in private drinking water?

Several states, including Colorado, New Hampshire, and North Carolina, have already initiated programs offering well testing and financial assistance for filters to protect against PFAS.

- After piloting its PFAS Testing and Assistance (TAP) program in one county in 2024, Colorado will expand it to three additional counties in 2025. The program covers the expenses of testing and a $79 nano pitcher (point-of-use) filter. Residents are eligible if PFOA and/or PFOS in their wells exceeds EPA MCLs of 4 ng/L; filters are free if their household income is ≤80% of the area median income and offered at a 30% discount if this income criteria is not met.

- The New Hampshire (NH) PFAS Removal Rebate Program for Private Wells offers greater flexibility and higher cost coverage than Colorado PFAS TAP, with reimbursements of up to $5000 offered for either point-of-entry or point-of-use treatment system installation and up to $10,000 offered for connection to a public water system. Though other residents may also participate in the program and receive delayed reimbursement, households earning ≤80% of the area median family income are offered the additional assistance of payment directly to a treatment installer or contractor (prior to installation) so as to relieve the applicant of fronting the cost. Eligibility is based on testing showing exceedances of the EPA MCLs of 4 ng/L for PFOA or PFOS or 10 ng/L for PFHxS, PFNA, or HFPO-DA (trademarked as “GenX”).

- The North Carolina PFAS Treatment System Assistance Program offers flexibility similar to New Hampshire in terms of the types of water treatment reimbursed, including multiple point-of-entry and point-of-use filter options as well as connection to public water systems. It is additionally notable for its tiered funding system, with reimbursement amounts ranging from $375 to $10,000 based on both the household’s income and the type of water treatment chosen. The tiered system categorizes program participants based on whether their household income is (1) <200%, (2) 200-400%, or (3) >400% the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). Also similar to New Hampshire, payments may be made directly to contractors prior to installation for the lowest income bracket, who qualify for full installation costs; others are reimbursed after the fact. This program uses the aforementioned EPA MCLs for PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, or HFPO-DA (“GenX”) and also recognizes the additional EPA MCL of a hazard index of 1.0 for mixtures containing two or more of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, or PFBS.

An opportunity exists to protect New Yorkers.

Launching a program in New York similar to those initiated in Colorado, New Hampshire, and North Carolina was among the priority initiatives described by New York Governor Kathy Hochul in the annual State of the State she delivered in January 2025. In particular, Hochul’s plans to improve water infrastructure included “a pilot program providing financial assistance for private well owners to replace or treat contaminated wells.” This was announced along with a $500 million additional investment beyond New York’s existing $5.5 billion dedicated to water infrastructure, which will also be used to “reduce water bills, combat flooding, restore waterways, and replace lead service lines to protect vulnerable populations, particularly children in underserved communities.” In early 2025, the New York Legislature introduced Senate Bill S3972, which intended to establish an installation grant program and a maintenance rebate program for PFAS removal treatment. Bipartisan interest in protecting the public from PFAS-contaminated drinking water is further evidenced by a hearing focused on the topic held by the NYS Assembly in November 2024.

Though these efforts would likely initially be confined to a smaller pilot program with limited geographic scope, such a pilot program would aim to inform a broader, statewide intervention. Challenges to planning an intervention of this scope include uncertainty surrounding both the total funding which would be allotted to such a program and its total costs. These costs will be dependent on factors such as the eligibility criteria employed by the state, the proportion of well owners who opt into sampling, and the proportion of tested wells found to have PFAS exceedances (which will further vary based on whether the state adopts EPA MCLs or NYS Department of Health MCLs, which are 10 ng/L for PFOA and PFOS). We allay the uncertainty associated with these numerous possibilities by estimating the numbers of wells serviced and associated costs under various combinations of 10 potential eligibility criteria, 5 possible rates (5, 25, 50, 75, and 100%) of PFAS testing among eligible wells, and 5 possible rates (5, 25, 50, 75, and 100%) of PFAS>MCL and subsequent POET installation among wells tested.

Scenario Analysis

Key findings

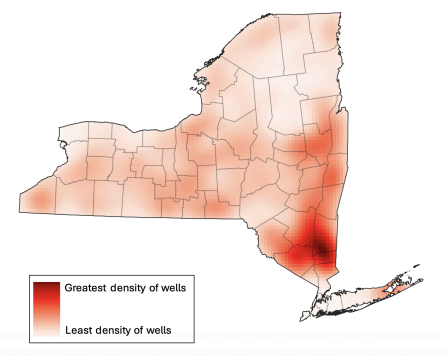

- Over 900,000 residences across NYS are supplied by private drinking wells (Figure 1).

- The three most costly scenarios were offering testing and installation rebates for (Table 1):

- Every private well owner (901,441 wells; $1,034,403,547)

- Every well located within a census tract designated as disadvantaged (based on NYS Disadvantaged Community (DAC) criteria) AND/OR belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000 (725,923 wells; $832,996,643)

- Every well belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000 (705,959 wells; $810,087,953)

- The three least costly scenarios were offering testing and installation rebates for (Table 1):

- Every well located within a census tract in which at least 51% of households earn below 80% of the area median income (22,835 wells; $26,191,688)

- Every well belonging to a household earning <100% of the Federal Poverty Level (92,661 wells; $106,328,398)

- Every well located within a census tract designated as disadvantaged (based on NYS Disadvantaged Community (DAC) criteria) (93,840 wells; $107,681,400)

- Of six income-based eligibility criteria, household income <$150,000 included the greatest number of wells, whereas location within a census tract in which at least 51% of households earn below 80% the area median income (a definition of low-to-moderate income used for programs coordinated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development), included the fewest wells. This amounts to a cost difference of $783,896,265 between these two eligibility scenarios.

- Six income-based criteria varied dramatically in terms of their inclusion of wells across NYS which fall within either disadvantaged or small communities (Table 2):

- For disadvantaged communities, this ranged from 12% (household income <100% federal poverty level) to 79% (income <$150,000) of all wells within disadvantaged communities being eligible.

- For small communities, this ranged from 2% (census tracts in which at least 51% of households earn below 80% area median income) to 83% (income <$150,000) of all wells within small communities being eligible.

Plan of Action

New York State is already considering a PFAS remediation program (e.g., Senate Bill S3972). The 2025 draft of the bill directed the New York Department of Environmental Conservation to establish an installation grant program and a maintenance rebate program for PFAS removal treatment, and establishes general eligibility criteria and per-household funding amounts. To our knowledge, S3972 did not pass in 2025, but its program provides a strong foundation for potential future action. Our suggestions below resolve some gaps in S3972, including additional detail that could be followed by the implementing agency and overall cost estimates that could be used by the Legislature when considering overall financial impacts.

Recommendation 1. Remediate all disadvantaged wells statewide

We recommend including every well located within a census tract designated as disadvantaged (based on NYS Disadvantaged Community (DAC) criteria) and/or belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000 as the eligibility criteria which protects the widest range of vulnerable New Yorkers. Using this criteria, we estimate a total program cost of approximately $833 million, or $167 million per year if the program were to be implemented over a 5-year period. Even accounting for the other projects which the state will be undertaking at the same time, this annual cost falls well within the additional $500 million which the 2025 State of the State reports will be added in 2025 to an existing $5.5 million state investment in water infrastructure.

Recommendation 2. Target disadvantaged census tracts and household incomes

Wells in DAC census tracts accounts for a variety of disadvantages. Including NYS DAC criteria helps to account for the heterogeneity of challenges experienced by New Yorkers by weighing statistically meaningful thresholds for 45 different indicators across several domains. These include factors relevant to the risk of PFAS exposure, such as land use for industrial purposes and proximity to active landfills.

Wells in low-income households account for cross-sectoral disadvantage. The DAC criteria alone is imperfect:

- Major criticisms include its underrepresentation of rural communities (only 13% of rural census tracts, compared to 26% of suburban and 48% of urban tracts, have been DAC-designated) and failure to account for some key stressors relevant to rural communities (e.g., distance to food stores and in-migration/gentrification).

- Another important note is that wells within DAC communities account for only 10% of all wells within NYS (Table 2). While wells within DAC-designated communities are important to consider, including only DAC wells in an intervention would therefore be very limiting.

- Whereas DAC designation is a binary consideration for an entire census tract, place-based criteria such as this are limited in that any real community comprises a spectrum of socioeconomic status and (dis)advantage.

The inclusion of income-based criteria is useful in that financial strain is a universal indicator of resource constraint which can help to identify the most-in-need across every community. Further, including income-based criteria can widen the program’s eligibility criteria to reach a much greater proportion of well owners (Table 2). Finally, in contrast to the DAC criteria’s binary nature, income thresholds can be adjusted to include greater or fewer wells depending on final budget availability.

- Of the income thresholds evaluated, income <$150,000 is recommended due to its inclusion not only of the greatest number of well owners overall, but also the greatest percentages of wells within disadvantaged and small communities (Table 2). These two considerations are both used by the EPA in awarding grants to states for water infrastructure improvement projects.

- As an alternative to selecting one single income threshold, the state may also consider maximizing cost effectiveness by adopting a tiered rebate system similar to that used by the North Carolina PFAS Treatment System Assistance Program.

Recommendation 3. Alternatives to POETs might be more cost-effective and accessible

A final recommendation is for the state to maximize the breadth of its well remediation program by also offering reimbursements for point-of-use treatment (POUT) systems and for connecting to public water systems, not just for POET installations. While POETs are effective in PFAS removal, they require invasive changes to household plumbing and prohibitively expensive ongoing maintenance, two factors which may give well owners pause even if they are eligible for an initial installation rebate. Colorado’s PFAS TAP program models a less invasive and extremely cost-effective POUT alternative to POETs. We estimate that if NYS were to provide the same POUT filters as Colorado, the total cost of the program (using the recommended eligibility criteria of location within a DAC-designated census tract and/or belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000) would be $163 million, or $33 million per year across 5 years. This amounts to a total decrease in cost of nearly $670 million if POUTs were to be provided in place of POETs. Connection to public water systems, on the other hand, though a significant initial investment, provides an opportunity to streamline drinking water monitoring and remediation moving forward and eliminates the need for ongoing and costly individual interventions and maintenance.

Conclusion

Well testing and rebate programs provide an opportunity to take preventative action against the serious health threats associated with PFAS exposure through private drinking water. Individuals reliant on PFAS-contaminated private wells for drinking water are likely to ingest the chemicals on a daily basis. There is therefore no time to waste in taking action to break this chain of exposure. New York State policymakers are already engaged in developing this policy solution; our recommendations can help both those making the policy and those tasked with implementing it to best serve New Yorkers. Our analysis shows that a program to mitigate PFAS in private drinking water is well within scope of current action and that fair implementation of such a program can help those who need it most and do so in a cost-effective manner.

While the Safe Drinking Water Act regulates the United States’ public drinking water supplies, there is no current federal government to regulate private wells. Most states also lack regulation of private wells. Introducing new legislation to change this would require significant time and political will. Political will to enact such a change is unlikely given resource limitations, concerns around well owners’ privacy, and the current time in which the EPA is prioritizing deregulation.

Decreasing blood serum levels is likely to decrease negative health impacts. Exposure via drinking water is particularly associated with elevated serum PFAS levels, while appropriate water filtration has demonstrated efficacy in reducing serum PFAS levels.

We estimated total costs assuming that 75% of eligible wells are tested for PFAS and that of these tested wells, 25% are both found to have PFAS exceedances and proceed to have filter systems installed. This PFAS exceedance/POET installation rate was selected because it falls between the rates of exceedances observed when private well sampling was conducted in Wisconsin and New Hampshire in recent years.

For states which do not have their own tools for identifying disadvantaged communities, the Social Vulnerability Index developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) may provide an alternative option to help identify those most in need.

Turning the Heat Up On Disaster Policy: Involving HUD to Protect the Public

This memo addresses HUD’s learning agenda question, “How do the impacts, costs, and resulting needs of slow-onset disasters compare with those of declared disasters, and what are implications for slow-onset disaster declarations, recovery aid programs, and HUD allocation formulas?” We examine this using heat events as our slow-onset disaster, and hurricanes as declared disaster.

Heat disasters, a classic “slow-onset disaster”, result in significant damages, which can exceed damage caused by more commonly declared disasters like hurricanes due to high loss of life from heat. The Federal Housing and Urban Development agency (HUD) can play an important role in heat disasters because most heat-related deaths occur in the home or among those without homes; therefore, the housing sector is a primary lever for public health and safety during extreme heat events. To enhance HUD’s ability to protect the public from extreme heat, we suggest enhancing interagency data collection/sharing to facilitate the federal disaster declarations needed for HUD engagement, working heat mitigation into HUD’s programs, and modifying allocation formulas, especially if a heat disaster is declared.

Challenge and Opportunity

Slow-Onset Disasters Never Declared As Disasters

Slow-onset disasters are defined as events that gradually develop over extended periods of time. Examples of slow-onset events like drought and extreme heat can evolve over weeks, months, or even years. By contrast, sudden-onset disasters like hurricanes, occur within a short and defined timeframe. This classification is used by international bodies such as the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).

HUD’s main disaster programs typically require a federal disaster declaration , making HUD action reliant on action by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) under the Stafford Act. However, to our knowledge, no slow-onset disaster has ever received a federal disaster declaration, and this category is not specifically addressed through federal policy.

We focus on heat disasters, a classic slow-onset disaster that has received a lot of attention recently. No heat event has been declared a federal disaster, despite several requests. Notable examples include the 1980 Missouri heat and drought events, the 1995 Chicago heat wave, which caused an estimated 700 direct fatalities, as well as the 2022 California heat dome and concurrent wildfires. For each request, FEMA determined that the events lacked sufficient “severity and magnitude” to qualify for federal assistance. FEMA holds a precedent that declared disasters need to have a discrete and time-bound nature, rather than a prolonged or seasonal atmospheric condition.

“How do the impacts, costs, and resulting needs of slow-onset disasters compare with those of declared disasters?”

Heat causes impacts in the same categories as traditional disasters, including mortality, agriculture, and infrastructure, but the impacts can be harder to measure due to the slow-onset nature. For example, heat-related illness and mortality as recorded in medical records are widely known to be significant underestimates of the true health impacts. The same is likely true across categories.

Sample Impacts

We analyze impacts within categories commonly considered by federal agencies–human mortality, agricultural impacts, infrastructure impacts, and costs for heat, and compare them to counterparts for hurricanes, a classic sudden-onset disaster. Other multi-sectoral reports of heat impacts have been compiled by other entities, including SwissRe and The Atlantic Council Climate Resilience Center.

We identified 3,478 deaths with a cause of “cataclysmic storms” (e.g., hurricanes; International Classification of Disease Code X.37) and 14,461 deaths with a cause of heat (X.30) between 1999-2020 using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC). It is important to note that the CDC database only includes death certificates that list heat as a cause of death, while it is widely recognized that this can be a significant underaccount. However, despite these limitations, CDC remains the most comprehensive national dataset for monitoring mortality trends.

HUD can play an important role in reducing heat mortality. In the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Dome, most of the deaths occurred indoors (reportedly 98% in British Columbia) and many in homes without adequate cooling. In hotter Maricopa County, Arizona, in 2024, 49% of all heat deaths were among people experiencing homelessness and 23% occurred in the home. Therefore, across the U.S., HUD programs could be a critical lever in protecting public health and safety by providing housing and ensuring heat-safe housing.

Agricultural Labor

Farmworkers are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat, and housing can be part of a solution to protect them. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), between 1992 to 2022, 986 workers across industry sectors died from exposure to heat, with agricultural workers being disproportionately affected. According to the Environmental Defense Fund, farmworkers in California are about 20 times more likely to die from heat-related stress, compared to the general population, and they estimate that the average U.S agricultural worker is exposed to 21 working days in the summer growing season that are unsafe due to heat. A study found that the number of unsafe working days due to extreme heat will double by midcentury, increasing occupational health risks and reducing labor productivity in critical sectors. Adequate cooling in the home could help protect outdoor workers by facilitating cooling periods during nonwork hours, another way in which HUD could have a positive impact on heat.

Infrastructure and Vulnerability

Rising temperatures significantly increase energy demand, particularly due to the widespread reliance on air conditioning. This surge in demand increases the risk of power outages during heat events, exacerbating public health risks due to potential grid failure. In urban areas, the built environment can add heat, while in rural areas residents are at greater risk due to the lack of infrastructure. This effect contributes to increased cooling costs and worsens air quality, compounding health vulnerabilities in low-income and urban populations. All of these impacts are areas where HUD could improve the situation through facilitating and encouraging energy-efficient homes and cooling infrastructure.

Costs

In all categories we examined, estimates of U.S.-wide costs due to extreme heat rivaled or exceeded costs of hurricanes. For mortality, the estimated economic impact of mortality (scaled by value of statistical life, VSL = $11.6 million) caused by extreme heat reached $168 billion, significantly exceeding the $40.3 billion in VSL losses from hurricanes during the same period. Infrastructure costs further reflect this imbalance. Extreme heat resulted in an estimated $100 billion in productivity loss in 2024 alone, with over 60% of U.S. counties currently experiencing reduced economic output due to heat-related labor stress. Meanwhile, Hurricanes Helene and Milton together generated $113 billion in damage during the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season.

Crop damage reveals the disproportionate toll of heat and drought, with 2024 seeing $11 billion in heat/drought impacts compared to $6.8 billion from hurricanes. The dairy industry experiences a substantial recurring burden from extreme heat, with annual losses of $1.5 billion attributed to heat-induced declines in production, reproduction, and livestock fatalities. Broader economic impacts from heat-related droughts are severe, including $14.5 billion in combined damages from the 2023 Southern and Midwestern drought and heatwave, and $22.1 billion from the 2022 Central and Eastern heat events. Comparatively, Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton produced $78.7 billion and $34.3 billion in damages, respectively. Extreme heat and drought exert long-term, widespread, and escalating economic pressures across public health, agriculture, energy, and infrastructure sectors. A reassessment of federal disaster frameworks is necessary to appropriately prioritize and allocate funds for heat-related resilience and response efforts.

Resulting Needs

Public Health and Medical Care: Immediate care and resources for heat stroke and exhaustion, dehydration, and respiratory issues are key to prevent deaths from heat exposure. Vulnerable populations including children, elderly, and unhoused are particularly at risk. There is an increased need for emergency medical services and access to cooling centers to prevent the exacerbation of heat stress and to prevent fatalities.

Cooling and Shelter: Communities require access to public cooling centers and for air conditioning. Clean water supply is also essential to maintain health.

Infrastructure and Repair: The use of air conditioning increases energy consumption, leading to power outages. Updated infrastructure is essential to handle demand and prevent blackouts. Building materials need to include heat-resistant materials to reduce Urban Heat Island effects.

Emergency Response Capacity: Emergency management systems need to be strengthened in order to issue early warnings, produce evacuation plans, and mobilize cooling centers and medical services. Reliable communication systems that provide real-time updates with heat index and health impacts will be key to improve community preparedness.

Financial Support and Insurance Coverage: Agricultural, construction, and service workers are populations which are vulnerable to heat events. Loss of income may occur as temperatures rise, and compensation must be given.

Social Support and Community Services: There is an increasing need for targeted services for the elderly, unhoused, and low-income communities. Outreach programs, delivery of cooling resources, and shelter options must be communicated and functional in order to reduce mortality. Resilience across these sectors will be improved as data definitions and methods are standardized, and when allocations of funding specifically for heat increase.

“What are implications for slow-onset disaster declarations, recovery aid programs, and HUD allocation formulas?”

Slow-onset disaster declarations

No heat event–or to our knowledge or other slow-onset disaster–has been declared a disaster under the Stafford Act, the primary legal authority for the federal government to provide disaster assistance. The statute defines a “major disaster” as “any natural catastrophe… which in the determination of the President causes damage of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant major disaster assistance to supplement the efforts and available resources of States, local governments, and disaster relief organizations in alleviating the damage, loss, hardship, or suffering caused thereby.” Though advocacy organizations have claimed that the reason for the lack of disaster declaration is because the Stafford Act omits heat, FEMA’s position is that amendment is unnecessary and that a heat disaster could be declared if state and local needs exceed their capacity during a heat event. This claim is credible, as the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a disaster without explicit mention in the Stafford Act.

Though FEMA’s official position has been openness to supporting an extreme-heat disaster declaration, the fact remains that none has been declared. There is opportunity to improve processes to enable future heat declarations, especially as heat waves affect more people more severely for more time. The Congressional Research Service suggests that much of the difficulty might stem from FEMA regulations focusing on assessment of uninsured losses makes it less likely that FEMA will recommend that the President declare a disaster. Heat events can be hard to pin down with defined time periods and locations, and the damage is often to health and other impacts that are slow to be quantified. Therefore, real-time monitoring systems that quantify multi-sectoral damage could be deployed to provide the information needed. Such systems have been designed for extreme heat, and similar systems are being tested for wildfire smoke–these systems could rapidly be put into use.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) plays a critical role in long-term disaster recovery, primarily by providing housing assistance and funding for community development initiatives (see table above). However, HUD’s ability to deploy emergency support is contingent upon disaster declaration under the Stafford Act and/or FEMA activation. This restriction limits HUD’s capacity to implement timely interventions, such as retrofitting public housing with cooling systems or providing emergency housing relief during extreme heat events.

Without formal recognition of a heat event as a disaster, HUD remains constrained in its ability to deliver rapid and targeted support to vulnerable populations facing escalating risks from extreme temperatures. Without declared heat disasters, the options for HUD engagement hinge on either modifying program requirements or supporting the policy and practice needed to enable heat disaster declarations.

HUD Allocation Formulas

Congress provides funding through supplemental appropriations to HUD following major disasters, and HUD determines how best to distribute funding based on disaster impact data. The calculations are typically based on Individual and Public Assistance data from FEMA, verified loss data from the Small Business Administration (SBA), claims from insurance programs such as the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), and housing and demographic data from the U.S Census Bureau and American Community Survey. CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT typically require that at least 70% and 50% of funds benefit low and moderate income (LMI) communities respectively. Funding is limited to areas where there has been a presidentially declared disaster.

For example, the Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2025 (approved on 12/21/2024) appropriated $12.039 billion for CDBG-Disaster Recovery funds (CDBG-DR) for disasters “that occurred in 2023 or 2024.” HUD focused its funding on areas with the most serious and concentrated unmet housing needs from within areas that experienced a declared disaster within the time frame. Data used to determine the severity of unmet housing needs included FEMA and SBA inspections of damaged homes; these data were used in a HUD formula.

Opportunities exist to adjust allocation formulas to be more responsive to extreme heat, especially if CDBG is activated for a heat disaster. For example, HUD is directed to use the funds “in the most impacted and distressed areas,” which it could interpret to include housing stock that is unlikely to protect occupants from heat.

Gaps

Extreme heat presents multifaceted challenges across public health, infrastructure, and agriculture, necessitating a coordinated and comprehensive federal response. The underlying gap is the lack of any precedent for declaring an extreme-heat disaster; without such a declaration, numerous disaster-related programs in HUD, FEMA, and other federal agencies cannot be activated. Furthermore, likely because of this underlying gap, disaster-related programs have not focused on protecting public health and safety from extreme heat despite its large and growing impact.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Improve data collection and sharing to enable disaster declarations.

Because lack of real-time, quantitative data of the type most commonly used by disaster declarations (i.e., uninsured losses; mortality) is likely a key hindrance to heat-disaster declarations, processes should be put in place to rapidly collect and share this data.

Health impacts could be tracked most easily by the CDC using the existing National Syndromic Surveillance System and by expanding the existing influenza-burden methodology, and by the National Highway Traffic Safety Association’s Emergency Medical Services Activation Surveillance Dashboard. To get real-time estimates of mortality, simple tools can be built that estimate mortality based on prior heatwaves; such tools are already being tested for wildfire smoke mortality. Tools like this use weather data as inputs and mortality as outputs, so many agencies could implement–NOAA, CDC, FEMA, and EPA are all potential hosts. Additional systems need to be developed to track other impacts in real time, including agricultural losses, productivity losses, and infrastructure damage.

To facilitate data sharing that might be necessary to develop some of the above tools, we envision a standardized national heat disaster framework modeled after the NIH Data Management and Sharing (DMS) policy. By establishing consistent definitions and data collection methods across health, infrastructure, and socioeconomic sectors, this approach would create a foundation for reliable, cross-sectoral coordination and evidence-based interventions. Open and timely access to data would empower decision-makers at all levels of government, while ethical protections—such as informed consent, data anonymization, and compliance with HIPAA and GDPR—would safeguard individual privacy. Prioritizing community engagement ensures that data collection reflects lived experiences and disparities, ultimately driving equitable, climate-resilient policies to reduce the disproportionate burden of heat disasters.

While HUD or any other agency could lead the collaboration, much of the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) partnership (HUD is a participant) is already set up to support data-sharing and new tools. NIHHIS is a partner network between many federal agencies and therefore has already started the difficult work of cross-agency collaboration. Existing partnerships and tools can be leveraged to rapidly provide needed information and collaboration, especially to develop real-time quantification of heat-event impacts that would facilitate declaration of heat disasters. Shifting agency priorities have reduced NIHHIS partnerships recently; these should be strengthened, potentially through Congressional action.

Recommendation 2. Incorporate heat mitigation throughout HUD programs

Because housing can play such an important role in heat health (e.g., almost all mortality from the 2021 Heat Dome in British Columbia occurred in the home; most of Maricopa County’s heat mortality is either among the unhoused or in the home), HUD’s extensive programs are in a strong position to protect health and life safety during extreme heat. Spurring resident protection could include gentle behavioral nudges to grant recipients, such as publishing guidance on regionally tailored heat protections for both new construction and retrofits. Because using CDBG funds for extreme heat is uncommon, HUD should publish guidance on how to align heat-related projects with CDBG requirements or how to incorporate heat-related mitigation into projects that have a different focus. In particular, it would be important to provide guidance on how extreme heat related activities meet National Objectives, as required by authorizing legislation.

HUD could also take a more active role, such as incentivizing or requiring heat-ready housing across their other programs, or even setting aside specific amounts of funds for this hazard. The active provision of funding would be facilitated by heat disaster declarations, so until that occurs it is likely that the facilitation guides suggested above are likely the best course of action.

HUD also has a role outside of disaster-related programs. For example, current HUD policy requires residents in Public Housing Agency (PHA) managed buildings to request funding relief to avoid surcharges from heavy use of air conditioning during heat waves; policy could be changed to proactively initiate that relief from HUD. In 2024, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary Richard Monocchio sent a note encouraging broad thinking to support residents through extreme heat, and such encouragement can be supported with agency action. While this surcharge might seem minor, ability to run air conditioning is key for protecting health, as many indoor heat deaths across Arizona to British Columbia occurred in homes that had air conditioning but it was off.

Recommendation 3. HUD Allocation Formula: Inclusion of Vulnerability Variables

When HUD is able to launch programs focused on extreme heat, likely only following an officially declared heat disaster, HUD allocation formulas should take into account heat-specific variables. This could include areas where heat mortality was highest, or, to enhance mitigation impact, areas with higher concentrations of at-risk individuals (older adults, children, individuals with chronic illness, pregnant people, low-income households, communities of color, individuals experiencing houselessness, and outdoor workers) at-risk infrastructure (older buildings, mobile homes, heat islands). By integrating heat-related vulnerability indicators in allocations formulas, HUD would make the biggest impact on the heat hazard.

Conclusion

Extreme heat is one of the most damaging and economically disruptive threats in the United States, yet it remains insufficiently recognized in federal disaster frameworks. HUD is an agency positioned to make the biggest impact on heat because housing is a key factor for mortality. However, strong intervention across HUD and other agencies is held back by lack of federal disaster declarations for heat. HUD can work together with its partner agencies to address this and other gaps, and thereby protect public health and safety.