Mobilizing Innovative Financial Mechanisms for Extreme Heat Adaptation Solutions in Developing Nations

Global heat deaths are projected to increase by 370% if direct action is not taken to limit the effects of climate change. The dire implications of rising global temperatures extend across a spectrum of risks, from health crises exacerbated by heat stress, malnutrition, and disease, to economic disparities that disproportionately affect vulnerable communities in the U.S. and in low- and middle-income countries. In light of these challenges, it is imperative to prioritize a coordinated effort at both national and international levels to enhance resilience to extreme heat. This effort must focus on developing and implementing comprehensive strategies to ensure the vulnerable developing countries facing the worst and disproportionate effects of climate change have the proper capacity for adaptation, as wealthier, developed nations mitigate their contributions to climate change.

To address these challenges, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) should mobilize finance through environmental impact bonds focused on scaling extreme heat adaptation solutions. USAID should build upon the success of the SERVIR joint initiative and expand it to include a partnership with NIHHIS to co-develop decision support tools for extreme heat. Additionally, the Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) within the USAID should take the lead in tracking and reporting on climate adaptation funding data. This effort will enhance transparency and ensure that adaptation and mitigation efforts are effectively prioritized. By addressing the urgent need for comprehensive adaptation strategies, we can mitigate the impacts of climate change, increase resilience through adaptation, and protect the most vulnerable communities from the increasing threats posed by extreme heat.

Challenge

Over the past 13 months, temperatures have hit record highs, with much of the world having just experienced their warmest June on record. Berkeley Earth predicts a 95% chance that 2024 will rank as the warmest year in history. Extreme heat drives interconnected impacts across multiple risk areas including: public health; food insecurity; health care system costs; climate migration and the growing transmission of life-threatening diseases.

Thus, as global temperatures continue to rise, resilience to extreme heat becomes a crucial element of climate change adaptation, necessitating a strategic federal response on both domestic and international scales.

Inequitable Economic and Health Impacts

Despite contributing least to global greenhouse gas emissions, low- and middle-income countries experience four times higher economic losses from excess heat relative to wealthier counterparts. The countries likely to suffer the most are those with the most humidity, i.e. tropical nations in the Global South. Two-thirds of global exposure to extreme heat occurs in urban areas in the Global South, where there are fewer resources to mitigate and adapt.

The health impacts associated with increased global extreme heat events are severe, with projections of up to 250,000 additional deaths annually between 2030 and 2050 due to heat stress, alongside malnutrition, malaria, and diarrheal diseases. The direct cost to the health sector could reach $4 billion per year, with 80% of the cost being shouldered by Sub-Saharan Africa. On the whole, low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) in the Global South experience a higher portion of adverse health effects from increasing climate variability despite their minimal contributions to global greenhouse emissions, underscoring a clear global inequity challenge.

This imbalance points to a crucial need for a focus on extreme heat in climate change adaptation efforts and the overall importance of international solidarity in bolstering adaptation capabilities in developing nations. It is more cost-effective to prepare localities for extreme heat now than to deal with the impacts later. However, most communities do not have comprehensive heat resilience strategies or effective early warning systems due to the lack of resources and the necessary data for risk assessment and management — reflected by the fact that only around 16% of global climate financing needs are being met, with far less still flowing to the Global South. Recent analysis from Climate Policy Initiative, an international climate policy research organization, shows that the global adaptation funding gap is widening, as developing countries are projected to require $212 billion per year for climate adaptation through 2030. The needs will only increase without direct policy action.

Opportunity: The Role of USAID in Climate Adaptation and Resilience

As the primary federal agency responsible for helping partner countries adapt to and build resilience against climate change, USAID announced multiple commitments at COP28 to advance climate adaptation efforts in developing nations. In December 2023, following COP28, Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and USAID Administrator Power announced that 31 companies and partners have responded to the President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience (PREPARE) Call to Action and committed $2.3 billion in additional adaptation finance. Per the State Department’s December 2023 Progress Report on President Biden’s Climate Finance Pledge, this funding level puts agencies on track to reach President Biden’s pledge of working with Congress to raise adaptation finance to $3 billion per year by 2024 as part of PREPARE.

USAID’s Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) leads the implementation of PREPARE. USAID’s entire adaptation portfolio was designed to contribute to PREPARE and align with the Action Plan released in September 2022 by the Biden Administration. USAID has further committed to better integrating adaptation in its Climate Strategy for 2022 to 2030 and established a target to support 500 million people’s adaptation efforts.

This strategy is complemented by USAID’s efforts to spearhead international action on extreme heat at the federal level, with the launch of its Global Sprint of Action on Extreme Heat in March 2024. This program started with the inaugural Global Heat Summit and ran through June 2024, calling on national and local governments, organizations, companies, universities, and youth leaders to take action to help prepare the world for extreme heat, alongside USAID Missions, IFRC and its 191-member National Societies. The executive branch was also advised to utilize the Guidance on Extreme Heat for Federal Agencies Operating Overseas and United States Government Implementing Partners.

On the whole, the USAID approach to climate change adaptation is aimed at predicting, preparing for, and mitigating the impacts of climate change in partner countries. The two main components of USAID’s approach to adaptation include climate risk management and climate information services. Climate risk management involves a “light-touch, staff-led process” for assessing, addressing, and adaptively managing climate risks in non-emergency development funding. The climate information services translate data, statistical analyses, and quantitative outputs into information and knowledge to support decision-making processes. Some climate information services include early warning systems, which are designed to enable governments’ early and effective action. A primary example of a tool for USAID’s climate information services efforts is the SERVIR program, a joint development initiative in partnership with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to provide satellite meteorology information and science to partner countries.

Additionally, as the flagship finance initiative under PREPARE, the State Department and USAID, in collaboration with the U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC), have opened an Adaptation Finance Window under the Climate Finance for Development Accelerator (CFDA), which aims to de-risk the development and scaling of companies and investment vehicles that mobilize private finance for climate adaptation.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1: Mobilize private capital through results-based financing such as environmental impact bonds

Results-based financing (RBF) has long been a key component of USAID’s development aid strategy, offering innovative ways to mobilize finance by linking payments to specific outcomes. In recent years, Environmental Impact Bonds (EIBs) have emerged as a promising addition to the RBF toolkit and would greatly benefit as a mechanism for USAID to mobilize and scale novel climate adaptation. Thus, in alignment with the PREPARE plan, USAID should launch an EIB pilot focused on extreme heat through the Climate Finance for Development Accelerator (CFDA), a $250 million initiative designed to mobilize $2.5 billion in public and private climate investments by 2030. An EIB piloted through the CFDA can help unlock public and private climate financing that focuses on extreme heat adaptation solutions, which are sorely needed.

With this EIB pilot, the private sector, governments, and philanthropic investors raise the upfront capital and repayment is contingent on the project’s success in meeting predefined goals. By distributing financial risk among stakeholders in the private sector, government, and philanthropy, EIBs encourage investment in pioneering projects that might struggle to attract traditional funding due to their novel or unproven nature. This approach can effectively mobilize the necessary resources to drive climate adaptation solutions.

This approach can effectively mobilize the necessary resources to drive climate adaptation solutions.

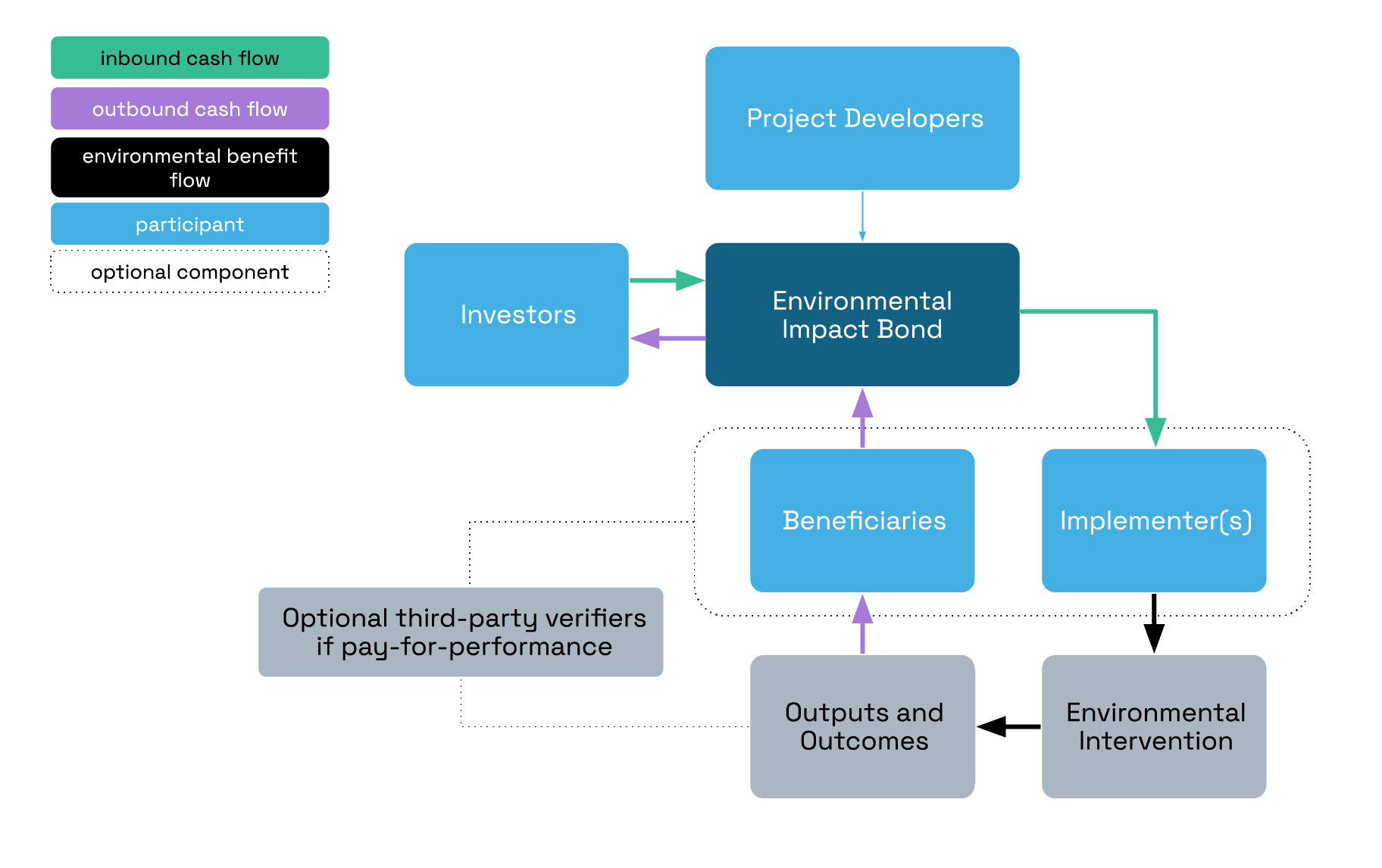

Overview of EIB structure, including cash flow (purple and green arrows) and environmental benefits (black arrows).

Adapted from Environmental Impact Bonds: a common framework and looking ahead

The USAID EIB pilot should focus on scaling projects that facilitate uptake and adoption of affordable and sustainable cooling systems such as solar-reflective roofing and other passive cooling strategies. In Southeast Asia alone, annual heat-related mortality is projected to increase by 295% by 2030. Lack of access to affordable and sustainable cooling mechanisms in the wake of record-shattering heat waves affects public health, food and supply chain, and local economies. An EIB that aims to fund and scale solar-reflective roofing (cool roofs) has the potential to generate high impact for the local population by lowering indoor temperature, reducing energy use for air conditioning, and mitigating the heat island effect in surrounding areas. Indonesia, which is home to 46.5 million people at high risk from a lack of access to cooling, has seen notable success in deploying cool roofs/solar-reflective roofing through the Million Cool Roof Challenge, an initiative of the Clean Cooling Collaborative. The country is now planning to scale production capacity of cool roofs and set up its first testing facility for solar-reflective materials to ensure quality and performance. Given Indonesia’s capacity and readiness, an EIB to scale cool roofs in Indonesia can be a force multiplier to see this cooling mechanism reach millions and spur new manufacturing and installation jobs for the local economy.

To mainstream EIBs and other innovative financial instruments, it is essential to pilot and explore more EIB projects. Cool roofs are an ideal candidate for scaling through an EIB due to their proven effectiveness as a climate adaptation solution, their numerous co-benefits, and the relative ease with which their environmental impacts can be measured (such as indoor temperature reductions, energy savings, and heat island index improvements). Establishing an EIB can be complex and time-consuming, but the potential rewards make the effort worthwhile if executed effectively. Though not exhaustive, the following steps are crucial to setting up an environmental impact bond:

Analyze ecosystem readiness

Before launching an environmental impact bond, it’s crucial to conduct an analysis to better understand what capacities already exist among the private and public sectors in a given country to implement something like an EIB. Additionally working with local civil society organizations is important to ensure climate adaptation projects and solutions are centered around the local community.

Determine the financial arrangement, scope, and risk sharing structure

Determine the financial structure of the bond, including the bond amount, interest rate, and maturity date. Establish a mechanism to manage the funds raised through the bond issuance.

Co-develop standardized, scientifically verified impact metrics and reporting mechanism

Develop a robust system for measuring and reporting the environmental impact projects; With key stakeholders and partner countries, define key performance indicators (KPIs) to track and report progress.

USAID has already begun to incubate and pilot innovative financing mechanisms in the global health space through development impact bonds. The Utkrisht Impact Bond, for example, is the world’s first maternal and newborn health impact bond, which aims to reach up to 600,000 pregnant women and newborns in Rajasthan, India. Expanding the use case of this financing mechanism in the climate adaptation sector can further leverage private capital to address critical environmental challenges, drive scalable solutions, and enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities to climate impacts.

Recommendation 2: USAID should expand the SERVIR joint initiative to include a partnership with NIHHIS and co-develop decision support tools such as an intersectional vulnerability map.

Building on the momentum of Administrator Power’s recent announcement at COP28, USAID should expand the SERVIR joint initiative to include a partnership with NOAA, specifically with NIHHIS, the National Integrated Heat Health Information System. NIHHIS is an integrated information system supporting equitable heat resilience, which is an important area that SERVIR should begin to explore. Expanded partnerships could begin with a pilot to map regional extreme heat vulnerability in select Southeast Asian countries. This kind of tool can aid in informing local decision makers about the risks of extreme heat that have many cascading effects on food systems, health, and infrastructure.

Intersectional vulnerabilities related to extreme heat refer to the compounding impacts of various social, economic, and environmental factors on specific groups or individuals. Understanding these intersecting vulnerabilities is crucial for developing effective strategies to address the disproportionate impacts of extreme heat. Some of these intersections include age, income/socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender, and occupation. USAID should partner with NIHHIS to develop an intersectional vulnerability map that can help improve decision-making related to extreme heat. Exploring the intersectionality of extreme heat vulnerabilities is critical to improving local decision-making and helping tailor interventions and policies to where it is most needed. The intersection between extreme heat and health, for example, is an area that is under-analyzed, and work in this area will contribute to expanding the evidence base.

The pilot can be modeled after the SERVIR-Mekong program, which produced 21 decision support tools throughout the span of the program from 2014-2022. The SERVIR-Mekong program led to the training of more than 1,500 people, the mobilization of $500,000 of investment in climate resilience activities, and the adoption of policies to improve climate resilience in the region. In developing these tools, engaging and co-producing with the local community will be essential.

Recommendation 3: USAID REFS and the State Department Office of Foreign Assistance should work together to develop a mechanism to consistently track and report climate funding flow. This also requires USAID and the State Department to develop clear guidelines on the U.S. approach to adaptation tracking and determination of adaptation components.

Enhancing analytical and data collection capabilities is vital for crafting effective and informed responses to the challenges posed by extreme heat. To this end, USAID REFS, along with the State Department Office of Foreign Assistance, should co-develop a mechanism to consistently track and report climate funding flow. Currently, both USAID and the State Department do not consistently report funding data on direct and indirect climate adaptation foreign assistance. As the Department of State is required to report on its climate finance contributions annually for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and biennially for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the two agencies should report on adaptation funding at similarly set, regular interval and make this information accessible to the executive branch and the general public. A robust tracking mechanism can better inform and aid agency officials in prioritizing adaptation assistance and ensuring the US fulfills its commitments and pledges to support global adaptation to climate change.

The State Department Office of Foreign Assistance (State F) is responsible for establishing standard program structures, definitions, and performance indicators, along with collecting and reporting allocation data on State and USAID programs. Within the framework of these definitions and beyond, there is a lack of clear definitions in terms of which foreign assistance projects may qualify as climate projects versus development projects and which qualify as both. Many adaptation projects are better understood on a continuum of adaptation and development activities. As such, this tracking mechanism should be standardized via a taxonomy of definitions for adaptation solutions.

Therefore, State F should create standardized mechanisms for climate-related foreign assistance programs to differentiate and determine the interlinkages between adaptation and mitigation action from the outset in planning, finance, and implementation — and thereby enhance co-benefits. State F relies on the technical expertise of bureaus, such as REFS, and the technical offices within them, to evaluate whether or not operating units have appropriately attributed funding that supports key issues, including indirect climate adaptation.

Further, announced at COP26, PREPARE is considered the largest U.S. commitment in history to support adaptation to climate change in developing nations. The Biden Administration has committed to using PREPARE to “respond to partner countries’ priorities, strengthen cooperation with other donors, integrate climate risk considerations into multilateral efforts, and strive to mobilize significant private sector capital for adaptation.” Co-led by USAID and the U.S. Department of State (State Department), the implementation of PREPARE also involves the Treasury, NOAA, and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). Other U.S. agencies, such as USDA, DOE, HHS, DOI, Department of Homeland Security, EPA, FEMA, U.S. Forest Service, Millennium Challenge Corporation, NASA, and U.S. Trade and Development Agency, will respond to the adaptation priorities identified by countries in National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and nationally determined contributions (NDCs), among others.

As USAID’s REFS leads the implementation of the PREPARE and hosts USAID’s Chief Climate Officer, this office should be responsible for ensuring the agency’s efforts to effectively track and consistently report climate funding data. The two REFS Centers that should lead the implementation of these efforts include the Center for Climate-Positive Development, which advises USAID leadership and supports the implementation of USAID’s Climate Strategy, and the Center for Resilience, which supports efforts to help reduce recurrent crises — such as climate change-induced extreme weather events — through the promotion of risk management and resilience in the USAID’s strategies and programming.

In making standardized processes to prioritize and track the flow of adaptation funds, USAID will be able to more effectively determine its progress towards addressing global climate hazards like extreme heat, while enhancing its ability to deliver innovative finance and private capital mechanisms in alignment with PREPARE. Additionally, standardization will enable both the public and private sectors to understand the possible areas of investment and direct their flows for relevant projects.

USAID uses the Standardized Program Structure and Definitions (SPSD) system — established by State F — to provide a common language to describe climate change adaptation and resilience programs and therefore enable the comparison and analysis of budget and performance data within a country, regionally or globally. The SPSD system uses the following categories: (1) democracy, human rights, and governance; (2) economic growth; (3) education and social services; (4) health; (5) humanitarian assistance; (6) peace and security; and (7) program development and oversight. Since 2016, climate change has been in the economic growth category and each climate change pillar has separate Program Areas and Elements. The SPSD consists of definitions for foreign assistance programs, providing a common language to describe programs. By utilizing a common language, information for various types of programs can be aggregated within a country, regionally, or globally, allowing for the comparison and analysis of budget and performance data.

Using the SPSD program areas and key issues, USAID categorizes and tracks the funding for its allocations related to climate adaptation as either directly or indirectly addressing climate adaptation. Funding that directly addresses climate adaptation is allocated to the “Climate Change—Adaptation” under SPSD Program Area EG.11 for activities that enhance resilience and reduce the vulnerability to climate change of people, places, and livelihoods. Under this definition, adaptation programs may have the following elements: improving access to science and analysis for decision-making in climate-sensitive areas or sectors; establishing effective governance systems to address climate-related risks; and identifying and disseminating actions that increase resilience to climate change by decreasing exposure or sensitivity or by increasing adaptive capacity. Funding that indirectly addresses climate adaptation is not allocated to a specific SPSD program area. It is funding that is allocated to another SPSD program area and also attributed to the key issue of “Adaptation Indirect,” which is for adaptation activities. The SPSD program area for these activities is not Climate Change—Adaptation, but components of these activities also have climate adaptation effects.

In addition to the SPSD, the State Department and USAID have also identified “key issues” to help describe how foreign assistance funds are used. Key issues are topics of special interest that are not specific to one operating unit or bureau and are not identified, or only partially identified, within the SPSD. As specified in the State Department’s foreign assistance guidance for key issues, “operating units with programs that enhance climate resilience, and/or reduce vulnerability to climate variability and change of people, places, and/or livelihoods are expected to attribute funding to the Adaptation Indirect key issue.”

Operating units use the SPSD and relevant key issues to categorize funding in their operational plans. State guidance requires that any USAID operating unit receiving foreign assistance funding must complete an operational plan each year. The purpose of the operational plan is to provide a comprehensive picture of how the operating unit will use this funding to achieve foreign assistance goals and to establish how the proposed funding plan and programming supports the operating unit, agency, and U.S. government policy priorities. According to the operational plan guidance, State F does an initial screening of these plans.

MDBs play a critical role in bridging the significant funding gap faced by vulnerable developing countries that bear a disproportionate burden of climate adaptation costs—estimated to reach up to 20 percent of GDP for small island nations exposed to tropical cyclones and rising seas. MDBs offer a range of financing options, including direct adaptation investments, green financing instruments, and support for fiscal adjustments to reallocate spending towards climate resilience. To be most sustainably impactful, adaptation support from MDBs should supplement existing aid with conditionality that matches the institutional capacities of recipient countries.

In January 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order (EO 14008) calling upon federal agencies and others to help domestic and global communities adapt and build resilience to climate change. Shortly thereafter in September 2022, the White House announced the launch of the PREPARE Action Plan, which specifically lays out America’s contribution to the global effort to build resilience to the impacts of the climate crisis in developing countries. Nineteen U.S. departments and agencies are working together to implement the PREPARE Action Plan: State, USAID, Commerce/NOAA, Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Treasury, DFC, Department of Defense (DOD) & U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), International Trade Administration (ITA), Peace Corps, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Energy (DOE), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Department of Transportation (DOT), Health and Human Services (HHS), NASA, Export–Import Bank of the United States (EX/IM), and Department of Interior (DOI).

Congress oversees federal climate financial assistance to lower-income countries, especially through the following actions: (1) authorizing and appropriating for federal programs and multilateral fund contributions, (2) guiding federal agencies on authorized programs and appropriations, and (3) overseeing U.S. interests in the programs. Congressional committees of jurisdiction include the House Committees on Foreign Affairs, Financial Services, Appropriations, and the Senate Committees on Foreign Relations and Appropriations, among others.