Protecting the Health of Americans in the Face of Extreme Weather

→ New Report: STAT Network highlights increasing threats, shows how states are rewriting playbooks in real time to protect American health, safety and economic vitality

→ First-ever survey reveals urgent need for coordinated action: only 5 percent of state health officials feel “very prepared”, 61 percent relied on federal funds now in flux.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — November 3, 2025 — A new report from the STAT Network reveals that extreme weather events are jeopardizing the health, safety and economic prospects of Americans. Published today in partnership with the Federation of American Scientists and supported by The Rockefeller Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the report reveals first-of-its-kind data from state public health officials in 45 states and territories on the urgent need for state-led coordination. The report also spotlights innovations that are being adopted and scaled through the STAT Network despite drastic cuts in federal funding to public health.

“States are navigating a new normal of extreme weather crises—heat waves following floods, wildfires overlapping with hurricanes—while the federal support and data tools they’ve relied on are eroding. No state should be left to shoulder this alone. Through our Extreme Weather & Health group and this report, we elevate what’s working on the ground as states are leading the response and offer a practical roadmap for acting at the speed and complexity of today’s hazards” said Stefanie Friedhoff, Professor of the Practice and STAT Network Lead, Brown University School of Public Health.

The STAT Network, which supports state public health officials across a range of pressing public health issues, started a dedicated extreme weather and health group in August 2024, serving as an essential connection point for collective problem solving in a shifting landscape. Of 136 state respondents who participated in the STAT Extreme Weather & Health survey shared with states in summer 2025:

→ only 5% feel “very prepared” to handle the escalating public health impacts of extreme weather

→ 61% prepared for extreme weather using federal funds that are now in flux

→ 39% cited federal partnerships as historically one of the most effective mechanisms to address impacts

→ 94% are concerned that socioeconomic disparities moderately (27%) or significantly (67%) contribute to unequal outcomes during extreme weather events in their state.

The new report, Protecting the Health of Americans in the Face of Extreme Weather: A Roadmap for Coordinated Action was developed to support these leaders at this moment of evolving challenges, needs and opportunities. The report details how states are pivoting their preparedness playbooks, showcases replicable new models, and identifies pressing gaps that funders, policymakers and thought leaders must still fill.

“Extreme weather events are no longer just natural disasters—they’re public health emergencies. From heat waves that overwhelm hospitals to floods that cut off access to care, Americans are feeling the strain in their communities. That’s why The Rockefeller Foundation launched the STAT Network at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic—to strengthen public health infrastructure through interstate collaboration and cross-sector partnerships. That same level of coordination is just as critical today as we face growing threats to health, safety, and economic opportunity” said Derek Kilmer, Senior Vice President for U.S. Program and Policy, The Rockefeller Foundation.

“One in three Americans report being personally affected by extreme weather in just the past two years – illustrating that extreme weather has become extremely common. The good news is that the negative health impacts of extreme weather are largely preventable. FAS is excited to partner with the STAT Network to help states step up as the federal government steps back, putting in place the innovative, evidence-based strategies we need to protect people and communities across the country,” said Dr. Hannah Safford Associate Director of Climate and Environment, Federation of American Scientists.

A changed landscape

Protecting the Health of Americans describes how extreme weather events have become more frequent, severe and widespread. From wildfires that quickly spiraled out of control in Maui and Los Angeles, to illness from extreme heat overloading emergency rooms across the Southwest, to sudden flash flooding from Hurricane Helene catching entire regions off-guard across Appalachia, it is clear that existing playbooks are no longer sufficient to respond to rapidly evolving threats. At the same time, cuts in 2025 at the Centers for Disease Control, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Weather Service and other federal agencies have removed the backbone of funding, data and technical assistance many states relied on.

States lead the way

Summarizing ongoing preparedness and response efforts across states, Protecting the Health of Americans offers three pillars for action and shares concrete, replicable examples that emerge from the STAT Extreme Weather & Health Network:

Collaboration. States like Minnesota and California are embedding public health voices in climate and infrastructure decisions, while North Carolina and Texas have demonstrated that shared frameworks like FEMA’s Community Lifelines can unite health, energy and emergency systems under one coordinated response. Partnerships break down silos and accelerate action.

Data. In North Carolina, advanced modeling now informs heat alerts based on real-time health and climate data; Illinois is developing predictive tools that warn hospitals before storms hit; and Alaska’s Local Environment Observer Network turns community observations into early-warning intelligence. States are making data more interoperable, localized and actionable.

Communication. Massachusetts amplified risk messaging on Triple E and West Nile via medical providers, community groups and local media. California is co-developing an interactive curriculum with community health workers on responding to poor air quality events. Kansas convenes a cross-sector Extreme Weather Events Work Group with community-based organizations to co-create practical toolkits. States are modernizing their communications capacity, building trusted messenger networks and moving past an over-focus on social media outreach.

The new report also includes case examples from states such as Oregon, Arizona and Texas that illustrate how housing insecurity, energy burden, medical dependence on electricity, and lack of access to timely, trusted information add additional burden for low-income, elderly and rural populations—and how systems-level interventions focused on energy resilience, targeted mitigation and partnerships with community-based organizations can save lives.

Insights from this report can serve as a pathway to building community resilience and protecting health from the impacts of extreme weather. Looking ahead, the STAT Network, the Federation of American Scientists and other collaborators look forward to working with state leaders and their partners to translate this roadmap into sustained progress.

The announcement comes ahead of the STAT Network’s participation in The Rockefeller Foundation and Heartland Forward’s “Big Bets for America” convening in Oklahoma City, where leaders across the public, private, and non-profit sectors will discuss opportunities to help communities flourish.

To learn more, download the full report.

Media Contact:

STAT Network:

Caroline Hoffman

Assistant Director of Content and Strategy

STAT Network at Brown University

caroline_hoffman2@brown.edu

FAS:

Katie McCaskey

Communications Manager, Media and PR

Federation of American Scientists

(202) 933-8857

kmccaskey@fas.org

About the STAT Network

At a time of unprecedented disruption in the U.S. public health system, the STAT Network serves as a strategic, nonpartisan, practice-focused partner to the state public health workforce in all 50 states as well as three territories. Originally created as the State and Territory Alliance for Testing by the Rockefeller Foundation in 2020 to meet the urgent need for more state-to-state collaboration during the COVID-19 pandemic, the network convenes state health leaders across the country on a weekly basis to problem-solve ongoing threats, share best practices, and support one another. Learn more about STAT at https://sites.brown.edu/stat/

About the STAT Extreme Weather & Health sub-network and this report

The STAT Extreme Weather and Health Group was created in August 2024 and meets monthly. Over 480 state officials from public health, preparedness and related departments in 45 states and some countries have attended these sessions over the past year. Between May and July 2025, the Network also fielded a comprehensive Extreme Weather and Health survey, which yielded 136 responses (78% from state officials, 10% from local health officials, and 12% from federal, academic and other partners to state teams). Responses came from 34 states, with near equal participation across the political spectrum. The STAT team also met individually with state- and county-level teams in more than 25 states for in-depth conversations about ongoing response needs and innovations. Protecting the Health of Americans summarizes findings across overall network presentations and discussions, the dedicated state-level survey, and state-level interviews.

About FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address urgent challenges. More information about our work at the intersection of climate change and health can be found at fas.org/initiative/climate-health.

The Federation of American Scientists’ Grace Wickerson Named to ‘Grist 50’ List

The scientist convened 70+ organizations calling for federal action to address the health harms of extreme heat

Washington, D.C. – September 16, 2025 – Grace Wickerson, the Federation of American Scientists’ Senior Manager, Climate and Health, today accepted a national recognition, the “Grist 50” award, bestowed by the editorial board of Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization. The annual Grist 50, started in 2016, recognizes fifty climate leaders working on unique and impactful solutions to the most pressing climate problems. Each year’s list is driven by hundreds of reader nominations. This is the first time someone from FAS has been recognized on Grist’s annual list for their work.

Extreme heat is an issue that now affects all 50 states and costs the country more than $160 billion annually. Wickerson led the development of the 2025 Heat Policy Agenda co-signed by more than 70 labor, industry, health, housing, environmental, academic and community associations and organizations. This resulted in over 100 policy proposals to address extreme heat.

“Grace and team have worked tirelessly to advance actionable, evidence-based policy solutions that will make our communities, and our country, more prepared to handle the growing threat of extreme heat. They have dug deep to understand the health effects of extreme heat and connect organizations across the country to call for all levels of government to take action,” says Dr. Hannah Safford, Associate Director of FAS Climate and Environment. “Their work is an outstanding example of policy entrepreneurship.”

FAS Extreme Heat Work

FAS is a leader in the development of evidence-based policy proposals to address extreme heat and wildfire, two hazards which worsen public health outcomes. With Wickerson, FAS has convened experts from around the country to surface strategies and solutions for federal, state, and local policymakers. The team’s latest work is Too Hot (Not) to Handle, a report on state and local strategies to address heat through resilient cooling.

In addition to the 2025 Heat Policy Agenda and the Resilient Cooling Strategy and Policy Toolkit, Wickerson and Autumn Burton, FAS Senior Associate, Climate and Health, continue to research and articulate the scope and depth of the extreme heat problem as it relates to physical landscapes and communities, public health and infrastructure, data and technology, and the workforce. Ongoing work and policy proposals include:

Economic Impacts of Extreme Heat: Energy

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Rural Communities

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Labor

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Federal Healthcare Spending

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Agriculture

Extreme Heat and Wildfire Smoke: Consequences for Communities

‘Grist 50’

This year’s Grist 50 includes entrepreneurs, artists, land stewards, and community advocates, and others working to address climate change. These stories are just a snapshot of the progress that is still unfolding all over the country — and a testament to the strength, diversity, and creativity of the many people pushing forward across the country. A full list of this year’s award recipients can be found here.

“It is an honor to be recognized amongst so many dedicated individuals. I look forward to connecting with fellow awardees in New York during Climate Week and working collectively to strengthen our respective efforts to address the climate crisis,” says Wickerson.

###

ABOUT GRIST 50

Grist is a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to highlighting climate solutions and uncovering environmental injustices. Since 2016, we have published our annual Grist 50, a list of climate leaders to know right now — people working on unique and impactful solutions to the most pressing climate problems of today. Each year’s list is driven by hundreds of reader nominations, and illustrates what a vibrant, diverse climate movement looks like, while amplifying stories of those making a difference. The 2025 list of awardees is here: https://grist.org/fix/grist-50/2025/

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address urgent challenges. Extreme heat work can be found at: https://fas.org/initiative/extreme-heat/

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Federal Healthcare Spending

Public health insurance programs, especially Medicaid, Medicare, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), are more likely to cover populations at increased risk from extreme heat, including low-income individuals, people with chronic illnesses, older adults, disabled adults, and children. When temperatures rise to extremes, these populations are more likely to need care for their heat-related or heat-exacerbated illnesses. Congress must prioritize addressing the heat-related financial impacts onthese programs. To boost the resilience of these programs to extreme heat, Congress should incentivize prevention by enabling states to facilitate health-related social needs (HRSN) pilots that can reduce heat-related illnesses, continue to support screenings for the social drivers of health, and implement preparedness and resilience requirements into the Conditions of Participation (CoPs) and Conditions for Coverage (CfCs) of relevant programs.

Extreme Heat Increases Fiscal Impacts on Public Insurance Programs

Healthcare costs are a function of utilization, which has been rapidly rising since 2010. Extreme heat is driving up utilization as more Americans seek medical care for heat-related illnesses. Extreme heat events are estimated to be annually responsible for nearly 235,000 emergency department visits and more than 56,000 hospital admissions, adding approximately $1 billion to national healthcare costs.

Heat-driven increases in healthcare utilization are especially notable for public insurance programs. One recent study found that there is a 10% increase in heat-related emergency department visits and a 7% increase in hospitalizations during heat wave days for low-income populations eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare. Further demonstrating the relationship between increased spending and extreme heat, the Congressional Budget Office found that for every 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, extreme temperatures cause an additional 156 emergency department visits and $388,000 in spending per day on average. These higher utilization rates also drive increases in Medicaid transfer payments from the federal government to help states cover rising costs. For every 10 additional days of extreme heat above 90°F, annual Medicaid transfer payments increase by nearly 1%, equivalent to an $11.78 increase per capita.

Additionally, Medicaid funds services for over 60% of nursing home residents. Yet Medicaid reimbursement rates often fail to cover the actual cost of care, leaving many facilities operating at a financial loss. This can make it difficult for both short-term and long-term care facilities to invest in and maintain the cooling infrastructure necessary to comply with existing requirements to maintain safe indoor temperatures. Further, many short-term and long-term care facilities do not have the emergency power back-ups that can keep the air conditioning on during extreme weather events and power outages, nor do they have emergency plans for occupant evacuation in case of dangerous indoor temperatures. This can and does subject residents to deadly indoor temperatures that can worsen their overall health outcomes.

The Impacts of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (H.R. 1) will have consequential impacts on federally-supported health insurance programs. The Congressional Budget Office projects that an estimated 10 million people could lose their healthcare coverage by 2034. Researchers have estimated that a loss of coverage could result in 50,000 preventable deaths. Further, health care facilities and hospitals will likely see funding losses as a result of Medicaid funding reductions. This will be especially burdensome to low-resourced hospitals, such as those serving rural areas, and result in reductions in available offerings for patients and even closure of facilities. States will need support navigating this new funding landscape while also identifying cost-effective measures and strategies to address the health-related impacts of extreme heat.

Advancing Solutions that Safeguard America’s Health from Extreme Heat

To address these impacts in this additionally challenged context, there are common-sense strategies to help people avoid extreme heat exposure. For example, access to safely cool indoor environments is one of the best preventative strategies for heat-related illness. In particular, Congress should create a demonstration pilot that provides eligible Medicare beneficiaries with cooling assistance and direct CMS to encourage Section 1115 demonstration waivers for HRSN related to extreme heat. Section 1115 waivers have enabled states to finance pilots for life-saving cooling devices and air filter distributions. These HRSN financing pilots have helped several states to work around the challenges of U.S. underinvestment in health and social services by providing a flexible vehicle to test methods of delivering and paying for healthcare services in Medicaid and CHIP. As Congress members explore these policies, they should consider the impact of H.R. 1’s new requirements for 1115 waiver’s proof of cost-neutrality.

To further support these efforts for heat interventions, Congress should direct CMS to continue Social Drivers of Health (SDOH) screenings as a part of Quality Reporting Programs and integrate questions about extreme heat exposure risks into the screening process. These screenings are critical for identifying the most vulnerable patients and directing them to the preventative services they need. This information will also be critical for identifying facilities that are treating high proportions of heat-vulnerable patients, which could then be sites for testing interventions like energy and housing assistance.

Congress should also direct the CMS to integrate heat preparedness and resilience requirements and metrics into the Conditions of Participation (CoPs) and Conditions for Coverage (CfCs), such as through the Emergency Preparedness Rule. This could include assessing the cooling capacity of a health care facility under extreme heat conditions, back-up power that is sufficient to maintain safe indoor temperatures, and policies for resident evacuation in the event of high indoor temperatures. For safety net facilities, such as rural hospitals and federally qualified health centers, Congress should consider allocating resources for technical assistance to assess these risks and the infrastructure upgrades.

Report Outlines Urgent, Decisive Action on Extreme Heat

‘Framework for a Heat-Ready Nation’ puts heat emergencies on the same footing as other natural disasters, reimagines how governments respond

Washington, D.C. – July 22, 2025 – Shattered heat records, heat domes, and prolonged heat waves cause thousands of deaths and hundreds of billions of dollars in lost productivity, damages, and economic disruptions. In 2023 alone, at least 2,300 people died from extreme heat, and true mortality could be greater than 10,000 annually. Workplaces are seeing $100 billion in lost productivity each year. Increased wear and tear on aging roads, bridges, and rail is increasing maintenance costs, with road maintenance costs expected to balloon to $26 billion annually by 2040. Extreme heat also puts roughly two-thirds of the country at risk of a blackout.

Extreme heat events that were uncommon in many places are becoming routine and longer lasting – and communities across the United States remain highly vulnerable.

To help prepare, the Federation of American Scientists has drawn upon experts from Sunbelt states to identify decisive actions to save lives during extreme heat events and prepare for longer heat seasons. The Framework for a Heat-Ready Nation, released today, calls for local, state, territory, Tribal, and federal governments to collaborate with community organizations, private sector partners and research institutions.

“The cost of inaction is not merely economic; it is measured in preventable illness, deaths and diminished livelihoods,” the report authors say. “Governments can no longer afford to treat extreme heat as business as usual or a peripheral concern.”

The Framework for a Heat-Ready Nation focuses on five measures to protect people, their livelihoods, and their communities:

- Establish leaders with responsibility and authority to address extreme heat. Leaders must coordinate actions across all relevant agencies and with non-governmental partners.

- Accurately assess extreme heat and its impacts in real time. Use the data to inform thresholds that trigger emergency response protocols, safeguards, and pathways to financial assistance.

- Prepare for extreme heat as an acute emergency as well as a chronic risk. Local governments should consider developing heat-response plans and integrating extreme temperatures into their long-term capital planning and resilience planning.

- When extreme heat thresholds are crossed, local, state, territory, Tribal and federal governments should activate response plans and consider emergency declarations. There should be a transparent and widely understood process for emergency responses to extreme heat that focus on protecting lives and livelihoods and safeguarding critical infrastructure.

- Develop strategies to plan for and finance long-term extreme heat impact reduction. Subnational governments can incentivize or require risk-reduction measures like heat-smart building codes and land-use planning, and state, territory, Tribal and federal governments can dedicate funding to support local investments in long-term preparedness.

Extreme heat in the Sunbelt region of the United States is a harbinger of what’s coming for the rest of the country. But the Sunbelt is also advancing solutions. In April 2025, representatives from states, cities, and regions across the U.S. Interstate 10 corridor from California to Florida, convened in Jacksonville, Florida for the Ten Across Sunbelt Cities Extreme Heat Exercise. Attendees worked to understand the available levers for government heat response, discussed their current efforts on extreme heat, and identified gaps that hinder both immediate response and long-term planning for future extreme heat events.

Through an analysis of efforts to date in the Sunbelt, gaps in capabilities, and identified opportunities, and analysis of previous calls to action around extreme heat, the Federation of American Scientists developed the Framework for a Heat-Ready Nation.

The report was produced with technical support from the Ten Across initiative associated with Arizona State University, and funding from the Natural Resources Defense Council.

###

About FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address national challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

Extreme Heat and Wildfire Smoke: Consequences for Communities

More Extreme Weather Leads to More Public Health Emergencies

Extreme heat and wildfire smoke both pose significant and worsening public health threats in the United States. Extreme heat causes the premature deaths of an estimated 10,000 people in the U.S. each year, while more frequent and widespread wildfire smoke exposure has set back decades of progress on air quality in many states. Importantly, these two hazards are related: extreme heat can worsen and prolong wildfire risk, which can increase smoke exposure.

Extreme heat and wildfire smoke events are independently becoming more frequent and severe, but what is overlooked is that they are often occurring in the same place at the same time. Emerging research suggests that the combined impact of these hazards may be worse than the sum of their individual impacts. These combined impacts have the potential to put additional pressure on already overburdened healthcare systems, public budgets, and vulnerable communities. Failing to account for these combined impacts could leave communities unprepared for these extreme weather events in 2025 and beyond.

To ensure resilience and improve public health outcomes for all, policymakers should consider the intersection of wildfire smoke and extreme heat at all levels of government. Our understanding of how extreme heat and wildfire smoke compound is still nascent, which limits national and local capacity to plan ahead. Researchers and policymakers should invest in understanding how extreme heat and wildfire smoke compound and use this knowledge to design synergistic solutions that enhance infrastructure resilience and ultimately save lives.

Intersecting Health Impacts of Extremely Hot, Smoky Days

Wildfire smoke and extreme heat can each be deadly. As mentioned, exposure to extreme heat causes the premature deaths of an estimated 10,000 people in the U.S. a year. Long-term exposure to extreme heat can also worsen chronic conditions like kidney disease, diabetes, hypertension, and asthma. Exposure to the primary component of wildfire smoke, known as fine particulate matter (PM2.5), contributes to an additional estimated 16,000 American deaths annually. Wildfire smoke exacerbates and causes various respiratory and cardiovascular effects along with other health issues, such as asthma attacks and heart failure, increasing risk of early death.

New research suggests that the compounding health impacts of heat and smoke co-exposure could be even worse. For example, a recent analysis found that the co-occurrence of extreme heat and wildfire smoke in California leads to more hospitalizations for cardiopulmonary problems than on heat days or smoke days alone.

Extreme heat also contributes to the formation of ground-level ozone. Like wildfire smoke, ground-level ozone can cause respiratory problems and exacerbate pre-existing conditions. This has already happened at scale: during the 2020 wildfire season, more than 68% of the western U.S. – about 43 million people – were affected in a single day by both ground-level ozone extremes and fine particulate matter from wildfire smoke.

Impacts on Populations Most Vulnerable to Combined Heat and Smoke

While extreme heat and wildfire smoke can pose health risks to everyone, there are some groups that are more vulnerable either because they are more likely to be exposed, they are more likely to suffer more severe health consequences when they are exposed, or both. Below, we highlight groups that are most vulnerable to extreme heat and smoke and therefore may be vulnerable to the compound impacts of these hazards. More research is needed to understand how the compound impacts will affect the health of these populations.

Housing-Vulnerable and Housing-Insecure People

Access to air conditioning at home and work, tree canopy cover, buildings with efficient wildfire smoke filtration and heat insulation and cooling capacities, and access to smoke centers are all important protective factors against the effects of extreme heat and/or wildfire smoke. People lacking these types of infrastructure are at higher risk for the health effects of these two hazards as a result of increased exposure. In California, for example, communities with lower incomes and higher population density experience a greater likelihood of negative health impacts from hazards like wildfire smoke and extreme heat.

Outdoor Workers

Representing about 33% of the national workforce, outdoor workers — farmworkers, firefighters, and construction workers — experience much higher rates of exposure to environmental hazards, including wildfire smoke and extreme heat, than other workers. Farmworkers are particularly vulnerable even among outdoor workers; in fact, they face a 35 times greater risk of heat exposure death than other outdoor workers. Additionally, outdoor workers are often lower-income, making it harder to afford protections and seek necessary medical care. Twenty percent of agricultural worker families live below the national poverty line.

Wildfire smoke exposure is estimated to have caused $125 billion in lost wages annually from 2007 to 2019 and extreme heat exposure is estimated to cause $100 billion in wage losses each year. Without any changes to policies and practice, these numbers are only expected to rise. These income losses may exacerbate inequities in poverty rates and economic mobility, which determine overall health outcomes.

Pregnant Mothers and Infants

Extreme heat and wildfire smoke also pose a significant threat to the health of pregnant mothers and their babies. For instance, preterm birth is more likely during periods of higher temperatures and during wildfire smoke events. This correlation is significantly stronger among people who were simultaneously exposed to extreme heat and wildfire smoke PM2.5.

Preterm birth comes with an array of risks for both the pregnant mothers and baby and is the leading cause of infant mortality. Babies born prematurely are more likely to have a range of serious health complications in addition to long-term developmental challenges. For the parent, having a preterm baby can have significant mental health impacts and financial challenges.

Children

Wildfire smoke and extreme heat both have significant impacts on children’s health, development, and learning. Children are uniquely vulnerable to heat because their bodies do not regulate temperatures as efficiently as adults, making it harder to cool down and putting their bodies under stress. Children are also more vulnerable to air pollution from wildfire smoke as they inhale more air relative to their weight than adults and because their bodies and brains are still developing. PM2.5 exposure from wildfires has been attributed to neuropsychological effects, such as ADHD, autism, impaired school performance, and decreased memory.

When schools remain open during extreme weather events like heat and smoke, student learning is impacted. Research has found that each 1℉ increase in temperature leads to 1% decrease in annual academic achievement. However, when schools close due to wildfire smoke or heat events, children lose crucial learning time and families must secure alternative childcare.

Low-income students are more likely to be in schools without adequate air conditioning because their districts have fewer funds available for school improvement projects. This barrier has only been partially remedied in recent years through federal investments.

Older Adults

Older adults are more likely to have multiple chronic conditions, many of which increase vulnerability to extreme heat, wildfire smoke, and their combined effects. Older adults are also more likely to take regular medication, such as beta blockers for heart conditions, which increase predisposition to heat-related illness.

The most medically vulnerable older adults are in long-term care facilities. There is currently a national standard for operating temperatures for long-term care facilities, requiring them to operate at or below 81℉. There is no correlatory standard for wildfire smoke. Preliminary studies have found that long-term care facilities are unprepared for smoke events; in some facilities the indoor air quality is no better than the outdoor air quality.

Challenges and Opportunities for the Healthcare Sector

The impacts of extreme heat and smoke have profound implications for public health and therefore for healthcare systems and costs. Extreme heat alone is expected to lead to $1 billion in U.S. healthcare costs every summer, while wildfire smoke is estimated to cost the healthcare system $16 billion every year from respiratory hospital visits and PM2.5 related deaths.

Despite these high stakes, healthcare providers and systems are not adequately prepared to address wildfire smoke, extreme heat, and their combined effects. Healthcare preparedness and response is limited by a lack of real-time information about morbidity and mortality expected from individual extreme heat and smoke events. For example, wildfire smoke events are often reported on a one-month delay, making it difficult to anticipate smoke impacts in real time. Further, despite the risks posed by heat and smoke independently and when combined, healthcare providers are largely not receiving education about environmental health and climate change. As a result, physicians also do not routinely screen their patients for health risk and existing protective measures, such as the existence of air conditioning and air filtration in the home.

Potential solutions to improve preparedness in the healthcare sector include developing more reliable real-time information about the potential impacts of smoke, heat, and both combined; training physicians in screening patients for risk of heat and smoke exposure; and training physicians in how to help patients manage extreme weather risks.

Challenges and Opportunities for Federal, State, and Local Governments

State and local governments have a role to play in building facilities that are resilient to extreme heat and wildfire smoke as well as educating people about how to protect themselves. However, funding for extreme heat and wildfire smoke is scarce and difficult for local jurisdictions in need to obtain. While some federal funding is available specifically to support smoke preparedness (e.g., EPA’s Wildfire Smoke Preparedness in Community Buildings Grant Program) and heat preparedness (e.g. NOAA NIHHIS’ Centers of Excellence), experts note that the funding landscape for both hazards is “limited and fragmented.” To date, communities have not been able to secure federal disaster funding for smoke or heat events through the Public Health Emergency Declaration or the Stafford Act. FEMA currently excludes the impacts on human health from economic valuations of losses from a disaster. As a result, many of these impacted communities never see investments from post-disaster hazard mitigation, which could potentially build community resilience to future events. Even if a declaration was made, it would likely be for one “event”, e.g. wildfire smoke or extreme heat, with recovery dollars targeted towards mitigating the impacts of that event. Without careful consideration, rebuilding and resilience investments might be maladaptive for addressing the combined impacts.

Next Steps

The Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission report offers a number of recommendations to improve how the federal government can better support communities in preparing for the impacts of wildfire smoke and acknowledges the need for more research on how heat and wildfire smoke compound. FAS has also developed a whole-government strategy towards extreme heat response, resilience, and preparedness that includes nearly 200 recommendations and notes the need for more data inputs on compounding hazards like wildfire smoke. Policymakers at the federal level should support research at the intersection of these topics and explore opportunities for providing technical assistance and funding that builds resilience to both hazards.

Understanding and planning for the compound impacts of extreme heat and wildfire smoke will improve public health preparedness, mitigate public exposure to extreme heat and wildfire smoke, and minimize economic losses. As the overarching research at this intersection is still emerging, there is a need for more data to inform policy actions that effectively allocate resources and reduce harm to the most vulnerable populations. The federal government must prioritize protection from both extreme heat and wildfire smoke, along with their combined effects, to fulfill its obligation to keep the public safe.

2025 Heat Policy Agenda

It’s official: 2024 was the hottest year on record. But Americans don’t need official statements to tell them what they already know: our country is heating up, and we’re deeply unprepared.

Extreme heat has become a national economic crisis: lowering productivity, shrinking business revenue, destroying crops, and pushing power grids to the brink. The impacts of extreme heat cost our Nation an estimated $162 billion in 2024 – equivalent to nearly 1% of the U.S. GDP.

Extreme heat is also taking a human toll. Heat kills more Americans every year than hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes combined. The number of heat-related illnesses is even higher. And even when heat doesn’t kill, it severely compromises quality of life. This past summer saw days when more than 100 million Americans were under a heat advisory. That means that there were days when it was too hot for a third of our country to safely work or play.

We have to do better. And we can.

Attached is a comprehensive 2025 Heat Policy Agenda for the Trump Administration and 119th Congress to better prepare for, manage, and respond to extreme heat. The Agenda represents insights from hundreds of experts and community leaders. If implemented, it will build readiness for the 2025 heat season – while laying the foundation for a more heat-resilient nation.

Core recommendations in the Agenda include the following:

- Establish a clear, sustained federal governance structure for extreme heat. This will involve elevating, empowering, and dedicating funds to the National Interagency Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS), establishing a National Heat Executive Council, and designating a National Heat Coordinator in the White House.

- Amend the Stafford Act to explicitly define extreme heat as a “major disaster”, and expand the definition of damages to include non-infrastructure impacts.

- Direct the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to consider declaring a Public Health Emergency in the event of exceptional, life-threatening heat waves, and fully fund critical HHS emergency-response programs and resilient healthcare infrastructure.

- Direct the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to include extreme heat as a core component of national preparedness capabilities and provide guidance on how extreme heat events or compounding hazards could qualify as major disasters.

- Finalize a strong rule to prevent heat injury and illness in the workplace, and establish Centers of Excellence to protect troops, transportation workers, farmworkers, and other essential personnel from extreme heat.

- Retain and expand home energy rebates, tax credits, LIHEAP, and the Weatherization Assistance Program, to enable deep retrofits that cut the costs of cooling for all Americans and prepare homes and other infrastructure against threats like power outages.

- Transform the built and landscaped environment through strategic investments in urban forestry and green infrastructure to cool communities, transportation systems to secure safe movement of people and goods, and power infrastructure to ready for greater load demand.

The way to prevent deaths and losses from extreme heat is to act before heat hits. Our 60+ organizations, representing labor, industry, health, housing, environmental, academic and community associations and organizations, urge President Trump and Congressional leaders to work quickly and decisively throughout the new Administration and 119th Congress to combat the growing heat threat. America is counting on you.

Executive Branch

Federal agencies can do a great deal to combat extreme heat under existing budgets and authorities. By quickly integrating the actions below into an Executive Order or similar directive, the President could meaningfully improve preparedness for the 2025 heat season while laying the foundation for a more heat-resilient nation in the long term.

Streamline and improve extreme heat management.

More than thirty federal agencies and offices share responsibility for acting on extreme heat. A better structure is needed for the federal government to seamlessly manage and build resilience. To streamline and improve the federal extreme heat response, the President must:

- Establish the National Integrated Heat-Health Information System (NIHHIS) Interagency Committee (IC). The IC will elevate the existing NIHHIS Interagency Working Group and empower it to shape and structure multi-agency heat initiatives under current authorities.

- Establish a National Heat Executive Council comprising representatives from relevant stakeholder groups (state and local governments, health associations, infrastructure professionals, academic experts, community organizations, technologists, industry, national laboratories, etc.) to inform the NIHHIS IC.

- Appoint a National Heat Coordinator (NHC). The NHC would sit in the Executive Office of the President and be responsible for achieving national heat preparedness and resilience. To be most effective, the NHC should:

- Work closely with the IC to create goals for heat preparedness and resilience in accordance with the National Heat Strategy, set targets, and annually track progress toward implementation.

- Each spring, deliver a National Heat Action Plan and National Heat Outlook briefing, modeled on the National Hurricane Outlook briefing, detailing how the federal government is preparing for forecasted extreme heat.

- Find areas of alignment with efforts to address other extreme weather threats.

- Direct the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the National Guard Bureau, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to create an incident command system for extreme heat emergencies, modeled on the National Hurricane Program.

- Direct the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to review agency budgets for extreme heat activities and propose crosscut budgets to support interagency efforts.

Boost heat preparedness, response, and resilience in every corner of our nation.

Extreme heat has become a national concern, threatening every community in the United States. To boost heat preparedness, response, and resilience nationwide, the President must:

- Direct FEMA to ensure that heat preparedness is a core component of national preparedness capabilities. At minimum, FEMA should support extreme heat regional scenario planning and tabletop exercises; incorporate extreme heat into Emergency Support Functions, the National Incident Management System, and the Community Lifelines program; help states, municipalities, tribes, and territories integrate heat into Hazard Mitigation Planning; work with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to provide language-accessible alerts via the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System; and clarify when extreme heat becomes a major disaster.

- Direct FEMA, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), and other agencies that use Benefit-Cost Analysis (BCA) for funding decisions to ensure that BCA methodologies adequately represent impacts of extreme heat, such as economic losses, learning losses, wage losses, and healthcare costs. This may require updating existing methods to avoid systematically and unintentionally disadvantaging heat-mitigation projects.

- Direct FEMA, in accordance with Section 322 of the Stafford Act, to create guidance on extreme heat hazard mitigation and eligibility criteria for hazard mitigation projects.

- Direct agencies participating in the Thriving Communities Network to integrate heat adaptation into place-based technical assistance and capacity-building resources.

- Direct the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to form a working group on accelerating resilience innovation, with extreme heat as an emphasis area. Within a year, the group should deliver a report on opportunities to use tools like federal research and development, public-private partnerships, prize challenges, advance market commitments, and other mechanisms to position the United States as a leader on game-changing resilience technologies.

Usher in a new era of heat forecasting, research, and data.

Extreme heat’s impacts are not well-quantified, limiting a systematic national response. To usher in a new era of heat forecasting, research, and data, the President must:

- Direct the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Weather Service (NWS) to expand the HeatRisk tool to include Alaska, Hawaii, and U.S. territories; provide information on real-time health impacts; and integrate sector-specific data so that HeatRisk can be used to identify risks to energy and the electric grid, health systems, transportation infrastructure, and more.

- Direct NOAA, through NIHHIS, to rigorously assess the impacts of extreme heat on all sectors of the economy, including agriculture, energy, health, housing, labor, and transportation. In tandem, NIHHIS and OMB should develop metrics tracking heat impact that can be incorporated into agency budget justifications and used to evaluate federal infrastructure investments and grant funding.

- Direct the NIHHIS IC to establish a new working group focused on methods for measuring heat-related deaths, illnesses, and economic impacts. The working group should create an inventory of federal datasets that track heat impacts, such as the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) datasets and power outage data from the Energy Information Administration.

- Direct NWS to define extreme heat weather events, such as “heat domes”, which will help unlock federal funding and coordinate disaster responses across federal agencies.

Protect workers and businesses from heat.

Americans become ill and even die due to heat exposure in the workplace, a moral failure that also threatens business productivity. To protect workers and businesses, the President must:

- Finalize a strong rule to prevent heat injury and illness in the workplace. The Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA)’s August 2024 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking is a crucial step towards a federal heat standard to protect workers. OSHA should quickly finalize this standard prior to the 2025 heat season.

- Direct OSHA to continue implementing the agency’s National Emphasis Program on heat, which enforces employers’ obligation to protect workers against heat illness or injury. OSHA should additionally review employers’ practices to ensure that workers are protected from job or wage loss when extreme heat renders working conditions unsafe.

- Direct the Department of Labor (DOL) to conduct a nationwide study examining the impacts of heat on the U.S. workforce and businesses. The study should quantify and monetize heat’s impacts on labor, productivity, and the economy.

- Direct DOL to provide technical assistance to employers on tailoring heat illness prevention plans and implementing cost-effective interventions that improve working conditions while maintaining productivity.

Prepare healthcare systems for heat impacts.

Extreme heat is both a public health emergency and a chronic stress to healthcare systems. Addressing the chronic disease epidemic will be impossible without treating the symptom of extreme heat. To prepare healthcare systems for heat impacts, the President must:

- Direct the HHS Secretary to consider using their authority to declare a Public Health Emergency in the event of an extreme heat wave.

- Direct HHS to embed extreme heat throughout the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), including by:

- Developing heat-specific response guidance for healthcare systems and clinics.

- Establishing thresholds for mobilizing the National Disaster Medical System.

- Providing extreme heat training to the Medical Reserve Corps.

- Simulating the cascading impacts of extreme heat through Medical Response and Surge Exercise scenarios and tabletop exercises.

- Direct HHS and the Department of Education to partner on training healthcare professionals on heat illnesses, impacts, risks to vulnerable populations, and treatments.

- Direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to integrate resilience metrics, including heat resilience, into its quality measurement programs. Where relevant, environmental conditions, such as chronic high heat, should be considered in newly required screenings for the social determinants of health.

- Direct the CDC’s Collaborating Office for Medical Examiners and Coroners to develop a standard protocol for surveillance of deaths caused or exacerbated by extreme heat.

Ensure affordably cooled and heat-resilient housing, schools, and other facilities.

Cool homes, schools, and other facilities are crucial to preventing heat illness and death. To prepare the build environment for rising temperatures, the President must:

Promote Housing and Cooling Access

- Direct HUD to protect vulnerable populations by (i) updating Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards to ensure that manufactured homes can maintain safe indoor temperatures during extreme heat, (ii) stipulating that mobile home park owners applying for Section 207 mortgages guarantee resident safety in extreme heat (e.g., by including heat in site hazard plans and allowing tenants to install cooling devices, cool walls, and shade structures), and (iii) guaranteeing that renters receiving housing vouchers or living in public housing have access to adequate cooling.

- Direct the Federal Housing Finance Agency to require that new properties must adhere to the latest energy codes and ensure minimum cooling capabilities in order to qualify for a Government Sponsored Enterprise mortgage.

- Ensure access to cooling devices as a medical necessity by directing the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to include high-efficiency air conditioners and heat pumps in Publication 502, which defines eligible medical expenses for a variety of programs.

- Direct HHS to (i) expand outreach and education to state Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) administrators and subgrantees about eligible uses of funds for cooling, (ii) expand vulnerable populations criteria to include pregnant people, and (iii) allow weatherization benefits to apply to cool roofs and walls or green roofs.

- Direct agencies to better understand population vulnerability to extreme heat, such as by integrating the Census Bureau’s Community Resilience Estimates for Heat into existing risk and vulnerability tools and updating the American Community Survey with a question about cooling access to understand household-level vulnerability.

- Direct the Department of Energy (DOE) to work with its Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) contractors to ensure that home energy audits consider passive cooling interventions like cool walls and roofs, green roofs, strategic placement of trees to provide shading, solar shading devices, and high-efficiency windows.

- Extend the National Initiative to Advance Building Codes (NIABC), and direct agencies involved in that initiative to (i) develop codes and metrics for sustainable and passive cooling, shade, materials selection, and thermal comfort, and (ii) identify opportunities to accelerate state and local adoption of code language for extreme heat adaptation.

Prepare Schools and Other Facilities

- Direct the Department of Education to collect data to better understand how schools are experiencing and responding to extreme heat, and to strengthen education and outreach on heat safety and preparedness for schools. This should include sponsored sports teams and physical activity programs. The Department should also collaborate with USDA on strategies to braid funding for green and shaded schoolyards.

- Direct the Administration for Children and Families to develop extreme heat guidance and temperature standards for Early Childhood Facilities and Daycares.

- Direct USDA to develop a waiver process for continuing school food service when extreme heat disrupts schedules during the school year.

- Direct the General Services Administration (GSA) to identify and pursue opportunities to demonstrate passive and resilient cooling strategies in public buildings.

- Direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to increase coordination with long-term care facilities during heat events to ensure compliance with existing indoor temperature regulations, develop plans for mitigating excess indoor heat, and build out energy redundancy plans, such as back-up power sources like microgrids.

- Direct the Bureau of Prisons, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to collect data on air conditioning coverage in federal prisons and detention facilities and develop temperature standards that ensure thermal safety of inmates and the prison and detention workforce.

- Direct the White House Domestic Policy Council to create a Cool Corridors Federal Partnership, modeled after the Urban Waters Federal Partnership. The partnership of agencies would leverage data, research, and existing grant programs for community-led pilot projects to deploy heat mitigation efforts, like trees, along transportation routes.

Legislative Branch

Congress can support the President in combating extreme heat by increasing funds for heat-critical federal programs and by providing new and explicit authorities for federal agencies.

Treat extreme heat like the emergency it is.

Extreme heat has devastating human and societal impacts that are on par with other federally recognized disasters. To treat extreme heat like the emergency it is, Congress must:

- Institutionalize and provide long-term funding for the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS), the NIHHIS Interagency Committee (IC), and the National Heat Executive Council (NHEC), including functions and personnel. NIHHIS is critical to informing heat preparedness, response, and resilience across the nation. An IC and NHEC will ensure federal government coordination and cross-sector collaboration.

- Create the National Heat Commission, modeled on the Wildfire Mitigation and Management Commission. The Commission’s first action should be creating a report for Congress on whole-of-government solutions to address extreme heat.

- Adopt H.R. 3965, which would amend the Stafford Act to explicitly include extreme heat in the definition of “major disaster”. Congress should also define the word “damages” in Section 102 of the Stafford Act to include impacts beyond property and economic losses, such as learning losses, wage losses, and healthcare costs.

- Direct and fund FEMA, NOAA, and CDC to establish a real-time heat alert system that aligns with the World Meteorological Organization’s Early Warnings for All program.

- Direct the Congressional Budget Office to produce a report assessing the costs of extreme heat to taxpayers and summarizing existing federal funding levels for heat.

- Appropriate full funding for emergency contingency funds for LIHEAP and the Public Health Emergency Program, and increase the annual baseline funding for LIHEAP.

- Update the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act to prohibit residential utilities from shutting off beneficiaries’ power during periods of extreme heat due to overdue bills.

- Adopt S. 2501, which would keep workers safe by requiring basic labor protections, such as water and breaks, in the event of indoor and outdoor extreme temperatures.

- Establish sector-specific Centers of Excellence for Heat Workplace Safety, beginning with military, transportation, and farm labor.

Build community heat resilience by readying critical infrastructure.

Investments in resilience pay dividends, with every federal dollar spent on resilience returning $6 in societal benefits. Our nation will benefit from building thriving communities that are prepared for extreme heat threats, adapted to rising temperatures, and capable of withstanding extreme heat disruptions. To build community heat resilience, Congress must:

- Establish the HeatSmart Grids Initiative as a partnership between DOE, FEMA, HHS, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). This initiative will ensure that electric grids are prepared for extreme heat, including risk of energy system failures during extreme heat and the necessary emergency and public health responses. This program should (i) perform national audits of energy security and building-stock preparedness for outages, (ii) map energy resilience assets such as long-term energy storage and microgrids, (iii) leverage technologies for minimizing grid loads such as smart grids and virtual power plants, and (iv) coordinate protocols with FEMA’s Community Lifelines and CISA’s Critical Infrastructure for emergency response.

- Update the LIHEAP formula to better reflect cooling needs of low-income Americans.

- Amend Title I of the Elementary & Secondary Education Act to clarify that Title I funds may be used for school infrastructure upgrades needed to avoid learning loss; e.g., replacement of HVAC systems or installation of cool roofs, walls, and pavements and solar and other shade canopies, green roofs, trees and green infrastructure to keep school buildings at safe temperatures during heat waves.

- Direct the HHS Secretary to submit a report to Congress identifying strategies for maximizing federal childcare assistance dollars during the hottest months of the year, when children are not in school. This could include protecting recent increased childcare reimbursements for providers who conform to cooling standards.

- Direct the HUD Secretary to submit a report to Congress identifying safe residential temperature standards for federally assisted housing units and proposing strategies to ensure compliance with the standards, such as extending utility allowances to cooling.

- Direct the DOT Secretary to conduct an independent third-party analysis of cool pavement products to develop metrics to evaluate thermal performance over time, durability, road subsurface temperatures, road surface longevity, and solar reflectance across diverse climatic conditions and traffic loads. Further, the analysis should assess (i) long-term performance and maintenance and (ii) benefits and potential trade-offs.

- Fund FEMA to establish a new federal grant program for community heat resilience, modeled on California’s “Extreme Heat and Community Resilience” program and in line with H.R. 9092. This program should include state agencies and statewide consortia as eligible grantees. States should be required to develop and adopt an extreme heat preparedness plan to be eligible for funds.

- Authorize and fund a new National Resilience Hub program at FEMA. This program would define minimum criteria that must be met for a community facility to be federally recognized as a resilience hub, and would provide funding to subsidize operations and emergency response functions of recognized facilities. Congress should also direct the FEMA Administrator to consider activities to build or retrofit a community facility meeting these criteria as eligible activities for Section 404 Hazard Mitigation Grants and funding under the Building Resilience Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program.

- Authorize and fund HHS to establish an Extreme Weather Resilient Health System Grant Program to prepare low-resource healthcare institutions (such as rural hospitals or federally qualified health centers) for extreme weather events.

- Fund the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to establish an Extreme Heat program and clearinghouse for design, construction, operation, and maintenance of buildings and infrastructure systems under extreme heat events.

- Fund HUD to launch an Affordable Cooling Housing Challenge to identify opportunities to lower the cost of new home construction and retrofits adapted to extreme heat.

- Expand existing rebates and tax credits (including HER, HEAR, 25C, 179D, Direct Pay) to include passive cooling tech such as cool walls, pavements, and roofs (H.R. 9894), green roofs, solar glazing, and solar shading. Revise 25C to be refundable at purchase.

- Authorize a Weatherization Readiness Program (H.R. 8721) to address structural, plumbing, roofing, and electrical issues, and environmental hazards with dwelling units unable to receive effective assistance from WAP, such as for implementing cool roofs.

- Fund the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) Urban and Community Forestry (UCF) Program to develop heat-adapted tree nurseries and advance best practices for urban forestry that mitigates extreme heat, such as strategies for micro forests.

Leveraging the Farm Bill to build national heat resilience.

Farm, food, forestry, and rural policy are all impacted by extreme heat. To ensure the next Farm Bill is ready for rising temperatures, Congress should:

- Double down on urban forestry, including by:

- Reauthorizing the UCF Grant program.

- Funding and directing the USFS UCF Program to support states, locals and Tribes on maintenance solutions for urban forests investments.

- Funding and authorizing a Green Schoolyards Grant under the UCF Program.

- Reauthorize the Farm Labor Stabilization and Protection Program, which supports employers in improving working conditions for farm workers.

- Reauthorize the Rural Emergency Health Care Grants and Rural Hospital Technical Assistance Program to provide resources and technical assistance to rural hospitals to prepare for emerging threats like extreme heat

- Direct the USDA Secretary to submit a report to Congress on the impacts of extreme heat on agriculture, expected costs of extreme heat to farmers (input costs and losses), consumers and the federal government (i.e. provision of SNAP benefits and delivery of insurance and direct payment for losses of agricultural products), and available federal resources to support agricultural and food systems adaptation to hotter temperatures.

- Authorize the following expansions:

- Agriculture Conservation Easement Program to include agrivoltaics.

- Environmental Quality Incentives Program to include facility cooling systems

- The USDA’s 504 Home Repair program to include funding for high-efficiency air conditioning and other sustainable cooling systems.

- The USDA’s Community Facilities Program to include funding for constructing resilience centers.These resilience centers should be constructed to minimum standards established by the National Resilience Hub Program, if authorized.

- The USDA’s Rural Business Development Grant program to include high-efficiency air conditioning and other sustainable cooling systems.

Funding critical programs and agencies to build a heat-ready nation.

To protect Americans and mitigate the $160+ billion annual impacts of extreme heat, Congress will need to invest in national heat preparedness, response, and resilience. The tables on the following pages highlight heat-critical programs that should be extended, as well as agencies that need more funding to carry out heat-critical work, such as key actions identified in the Executive section of this Heat Policy Agenda.

Enhancing Public Health Preparedness for Climate Change-Related Health Impacts

The escalating frequency and intensity of extreme heat events, exacerbated by climate change, pose a significant and growing threat to public health. This problem is further compounded by the lack of standardized education and preparedness measures within the healthcare system, creating a critical gap in addressing the health impacts of extreme heat. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), especially the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity (OCCHE) can enhance public health preparedness for the health impacts of climate change. By leveraging funding mechanisms, incentives, and requirements, HHS can strengthen health system preparedness, improve health provider knowledge, and optimize emergency response capabilities.

By focusing on interagency collaboration and medical education enhancement, strategic measures within HHS, the healthcare system can strengthen its resilience against the health impacts of extreme heat events. This will not only improve coding accuracy, but also enhance healthcare provider knowledge, streamline emergency response efforts, and ultimately mitigate the health disparities arising from climate change-induced extreme heat events. Key recommendations include: establishing dedicated grant programs and incentivizing climate-competent healthcare providers; integrating climate-resilience metrics into quality measurement programs; leveraging the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act to enhance ICD-10 coding education; and collaborating with other federal agencies such as the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and the Department of Defense (DoD) to ensure a coordinated response. The implementation of these recommendations will not only address the evolving health impacts of climate change but also promote a more resilient and prepared healthcare system for the future.

Challenge

The escalating frequency and intensity of extreme heat events, exacerbated by climate change, pose a significant and growing threat to public health. The scientific consensus, as documented by reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the National Climate Assessment, reveals that vulnerable populations, such as children, pregnant people, the elderly, and marginalized communities including people of color and Indigenous populations, experience disproportionately higher rates of heat-related illnesses and mortality. The Lancet Countdown’s 2023 U.S. Brief underscores the escalating threat of fossil fuel pollution and climate change to health, highlighting an 88% increase in heat-related mortality among older adults and calling for urgent, equitable climate action to mitigate this public health crisis.

Inadequacies in Current Healthcare System Response

Reports from healthcare institutions and public health agencies highlight how current coding practices contribute to the under-recognition of heat-related health impacts in vulnerable populations, exacerbating existing health disparities. The current inadequacies in ICD-10 coding for extreme heat-related health cases hinder effective healthcare delivery, compromise data accuracy, and impede the development of targeted response strategies. Challenges in coding accuracy are evident in existing studies and reports, emphasizing the difficulties healthcare providers face in accurately documenting extreme heat-related health cases. An analysis of emergency room visits during heat waves further indicates a gap in recognition and coding, pointing to the need for improved medical education and coding practices. Audits of healthcare coding practices reveal inconsistencies and inaccuracies that stem from a lack of standardized medical education and preparedness measures, ultimately leading to underreporting and misclassification of extreme heat cases. Comparative analyses of health data from regions with robust coding practices and those without highlight the disparities in data accuracy, emphasizing the urgent need for standardized coding protocols.

There is a crucial opportunity to enhance public health preparedness by addressing the challenges associated with accurate ICD-10 coding in extreme heat-related health cases. Reports from government agencies and economic research institutions underscore the economic toll of extreme heat events on healthcare systems, including increased healthcare costs, emergency room visits, and lost productivity due to heat-related illnesses. Data from social vulnerability indices and community-level assessments emphasize the disproportionate impact of extreme heat on socially vulnerable populations, highlighting the urgent need for targeted policies to address health disparities.

Opportunity

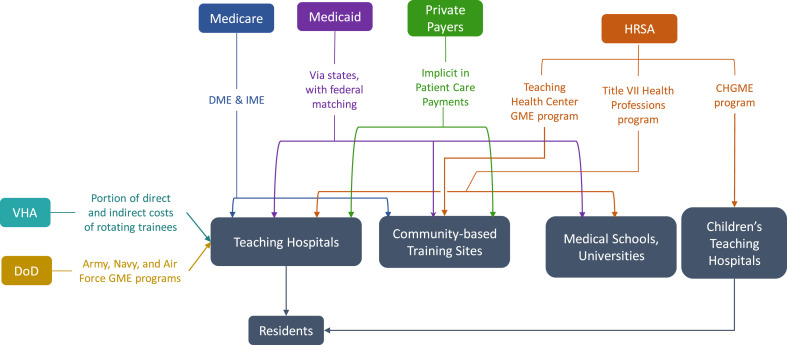

As Medicare is the largest federal source of Graduate Medical Education (GME) funding (Figure 1), the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) play a critical role in developing coding guidelines. Thus, it is essential for HHS, CMS, and other pertinent coordinating agencies to be involved in the process for developing climate change-informed graduate medical curricula.

By focusing on medical education enhancement, strategic measures within HHS, and fostering interagency collaboration, the healthcare system can strengthen its resilience against the health impacts of extreme heat events. Improving coding accuracy, enhancing healthcare provider knowledge, streamlining emergency response efforts, and mitigating health disparities related to extreme heat events will ultimately strengthen the healthcare system and foster more effective, inclusive, and equitable climate and health policies. Improving the knowledge and training of healthcare providers empowers them to respond more effectively to extreme heat-related health cases. This immediate response capability contributes to the overarching goal of reducing morbidity and mortality rates associated with extreme heat events and creates a public health system that is more resilient and prepared for emerging challenges.

The inclusion of ICD-10 coding education into graduate medical education funded by CMS aligns with the precedent set by the Pandemic and All Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA), emphasizing the importance of preparedness and response to public health emergencies. Similarly, drawing inspiration from the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act), which promotes the adoption of electronic health records (EHR) systems, presents an opportunity to modernize medical education and ensure the seamless integration of climate-related health considerations. This collaborative and forward-thinking approach recognizes the interconnectedness of health and climate, offering a model that can be applied to various health challenges. Integrating mandates from PAHPA and the HITECH Act serves as a policy precedent, guiding the healthcare system toward a more adaptive and proactive stance in addressing climate change impacts on health.

Conversely, the consequences of inaction on the health impacts of extreme heat extend beyond immediate health concerns. They permeate through the fabric of society, widening health disparities, compromising the accuracy of health data, and undermining emergency response preparedness. Addressing these challenges requires a proactive and comprehensive approach to ensure the well-being of communities, especially those most vulnerable to the effects of extreme heat.

Plan of Action

The following recommendations aim to facilitate public health preparedness for extreme heat events through enhancements in medical education, strategic measures within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and fostering interagency collaboration.

Recommendation 1a. Integrate extreme heat training into the GME curriculum.

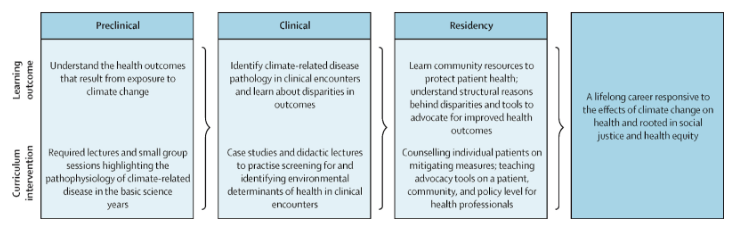

Integrating modules on extreme heat-related health impacts and accurate ICD-10 coding into medical education curricula is essential for preparing future healthcare professionals to address the challenges posed by climate change. This initiative will ensure that medical students receive comprehensive training on identifying, treating, and documenting extreme heat-related health cases. Sec. 304. Core Education and Training of the PAHPA provides policy precedent to develop foundational health and medical response curricula and training materials by modifying relevant existing programs to enhance responses to public health emergencies. Given the prominence of Medicare in funding medical residency training, policies that alter Medicare GME can affect the future physician supply and can be used to address identified healthcare workforce priorities related to extreme heat (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A model for comprehensive climate and medical education (adapted from Jowell et al. 2023)

Recommendation 1b. Collaborate with Veterans Health Administration Training Programs.

Partnering with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to extend climate-related health coding education to Veterans Health Administration (VHA) training programs will enhance the preparedness of healthcare professionals within the VHA system to manage and document extreme heat-related health cases among veteran populations.

Recommendation 2. Collaborate with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

Establishing a collaborative research initiative with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) will facilitate the in-depth exploration of accurate ICD-10 coding for extreme heat-related health cases. This should be accomplished through the following measures:

Establish joint task forces. CMS, NCHS, and AHRQ should establish joint research initiatives focused on improving ICD-10 coding accuracy for extreme heat-related health cases. This collaboration will involve identifying key research areas, allocating resources, and coordinating research activities. Personnel from each agency, including subject matter experts and researchers from the EPA, NOAA, and FEMA, will work together to conduct studies, analyze data, and publish findings. By conducting systematic reviews, developing standardized coding algorithms, and disseminating findings through AHRQ’s established communication channels, this initiative will improve coding practices and enhance healthcare system preparedness for extreme heat events.

Develop standardized coding algorithms. AHRQ, in collaboration with CMS and NCHS, will lead efforts to develop standardized coding algorithms for extreme heat-related health outcomes. This involves reviewing existing coding practices, identifying gaps and inconsistencies, and developing standardized algorithms to ensure consistent and accurate coding across healthcare settings. AHRQ researchers and coding experts will work closely with personnel from CMS and NCHS to draft, validate, and disseminate these algorithms.

Integrate into Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) programs. Establish collaborative partnerships between the VA and other federal healthcare agencies, including CMS, HRSA, and DoD, to integrate education on ICD-10 coding for extreme heat-related health outcomes into CQI programs. Regularly assess the effectiveness of training initiatives and adjust based on feedback from healthcare providers. For example, CMS currently requires physicians to screen for the social determinants of health and could include level of climate and/or heat risk within that screening assessment.

Allocate resources. Each agency will allocate financial resources, staff time, and technical expertise to support collaborative activities. Budget allocations will be based on the scope and scale of specific initiatives, with funds earmarked for research, training, data sharing, and evaluation efforts. Additionally, research funding provided through PHSA Titles VII and VIII can support studies evaluating the effectiveness of educational interventions on climate-related health knowledge and practice behaviors among healthcare providers.

Recommendation 3. Leverage the HITECH Act and EHR.

Recommendation 4. Establish climate-resilient health system grants to incentivize state-level climate preparedness initiatives