Using Trade to Build Stability in South Asia

Former Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto once said, “If India builds the bomb, Pakistan will eat grass, even go hungry, but we will get our own.”1 Today, Pakistan has had the bomb for more than 13 years2, yet according to expert estimates the Pakistanis are building nuclear weapons faster than anyone else in the world.3 Meanwhile, Pakistan’s economy continues to deteriorate at such a rate that its people resorting to grass as sustenance may actually become a reality. Economists forecast that Pakistan’s GDP must expand at a minimum of 3 percent just to maintain current living standards and keep up with the rapidly expanding population.4

With the rapid spread of Islamic extremism and tensions growing daily between the civilian government, the courts, and the military, the prospect of an increasing number of nuclear weapons in Pakistan sparks fear that one of these weapons could fall into the wrong hands. Given the risks involved with a destabilized Pakistan, there is an obvious and pressing need to improve the security situation in South Asia, a region home to nearly one-fifth of the world’s population.

The tensions between India and Pakistan date back to their partition in 1947 into separate countries. Since then, the two have fought a total of four wars, mostly over the disputed territory of Kashmir. Pakistan has been suspected of supporting a militant insurgency in Indian administered Kashmir since the mid-1980s, while India is alleged to support an insurgency in Pakistan’s Balochistan Province.5 This strained relationship prompted the development of both countries’ nuclear weapons programs, while security concerns on Pakistan’s western and eastern borders – partly a legacy of Pakistani and U.S. support for militants along its western frontier during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 19796 – have led to disproportionate military influence in Pakistan’s politics and administration. As a result, the country has experienced three periods of military dictatorship, which have severely limited the country’s ability to build and maintain viable democratic institutions.7

Given the bleak situation between India and Pakistan is it even possible to build better relations? Improving bilateral trade is one way to potentially foster collaboration between the two states, but the last 65 years have demonstrated how difficult it is for India and Pakistan to make progress on security related issues. Kashmir remains in dispute: thousands of Indian and Pakistani soldiers remain perched high on the Siachen Glacier, a desolate piece of ice where more soldiers die from avalanches than enemy fire. Nevertheless, there remains a real threat that conflict can erupt anytime at Siachen, the world’s highest battlefield. Simultaneously, a significant portion of Indian and Pakistani society remains marred in poverty. The collaboration required to build better trade relations has the potential to positively impact the situation of both countries and perhaps bring India and Pakistan closer together.

South Asia Today

India and Pakistan face precarious times: millions remain in poverty on both sides of the border, as both countries face deteriorating rates of economic growth. Pakistan is forecasted to miss its target of 4.2 percent GDP growth rate this year, while India has had to cut its GDP growth forecast to 5 percent.89 At the same time, a continuing population boom means that this modest economic growth will most likely not be enough to improve upon or even maintain the quality of life for Indians and Pakistanis. With the anticipated U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in December 2014 there is additional potential for instability in the region, as a reduction in Western engagement could spark greater unrest in the tribal belt separating Pakistan and Afghanistan. Instability and violence from this region could spread to the rest of Afghanistan and Pakistan, ultimately negatively impacting India as well.

Improving trade relations and engaging in greater trade could be a way for India and Pakistan to improve their economies. Although the situation they face is not promising, the domestic political situation in both countries suggests that now is the best time to make improvements in trade relations a reality. With the May 11,2013 Pakistani elections, Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) has returned to power with a solid parliamentary majority.10 Sharif has already indicated his support for improved bilateral trade relations, reaching out to his Indian counterpart Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, and inviting him to visit Pakistan.11 Similarly, Singh has also expressed his intention to build better relations with Pakistan, specifically focusing on greater trade.12 While these are promising signs for bilateral relations, it remains to be seen whether these two leaders will follow these initial overtures with real progress. Although Sharif launched a series of ambitious economic reforms during his first term, his previous two terms in office were characterized by corruption.13Singh’s government has also seen several major corruption scandals, as well as an inability to implement key economic reforms such as further liberalization of the Indian economy to encourage foreign investment.14

However, both leaders are under pressure to improve their domestic economic situation. Pakistanis elected Sharif with a wide margin of support, but will quickly become impatient if he does not deliver on his promise to improve the economic situation. Across the border in India, Singh and his Indian National Congress (INC) face parliamentary election in 2014 – signs of economic progress and reform are vital if they are to be reelected. Meanwhile, the INC’s main opposition, the Bharatya Janta Party (BJP), recently experienced a setback by losing a critical state election in Karanataka.15 Despite this, Singh and his government are still under immense pressure to improve India’s economy. Because of these domestic political situations, inaction on improving the economy is a risk that neither Nawaz Sharif nor Manmohan Singh can afford to take. Greater bilateral trade is one policy that both Sharif and Singh can adopt to improve the economies of their countries.

To boost trade from current levels, India and Pakistan must take several key steps.

1) Develop a uniform, jointly developed trade policy

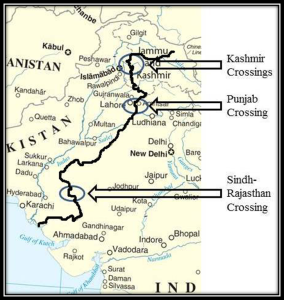

Different policies govern trade at the Punjab crossing, the two Kashmiri crossings, and by sea – a common trade policy governing what goods can be traded and how trade is conducted across the various routes between India and Pakistan does not yet exist. The two countries need to establish a clear joint trade policy that outlines how present trade policies between India and Pakistan will evolve in the coming years, so that ultimately the same trade policies and practices are in place regardless of the border crossing used.

2) Pakistan must grant MFN status to India

Setting a clearer and more cohesive bilateral trade policy depends on Pakistan extending “Most Favored Nation” status to India. MFN status is important in international trade because it means that one country will not discriminate against another country in terms of trade. India has granted Pakistan MFN status since 1996. Pakistan granted India MFN status briefly in 2011, but then retracted India’s MFN status due to opposition from several key domestic industries such as agriculture and automotive sectors. Granting India MFN status would mean that Pakistan must extend the same trade preferences to India as Pakistan currently does to other countries that it has granted MFN status.

To avoid retracting this MFN status as it did in 2011, Pakistan and India must adopt a gradual process with a concrete timeline, with the ultimate goal to extend MFN status to India. The gradual process of extending MFN status could be incorporated into the overall objective of developing a clear, unified Indo-Pakistan trade policy. With a clear timeline, domestic industries in Pakistan that could be adversely affected by liberalization of trade with India have a chance to prepare and adjust to these economic shifts. To take this preparation a step further, the two countries should establish cross-border collaboration in sectors that would be the hardest hit from further Indo-Pakistan trade liberalization. Through these joint collaborations, businessmen from both countries could work together to manage the impact of extending MFN status to India. Altogether, these steps would minimize the pain felt by those who would lose out from Indo-Pakistan trade liberalization.

3) Improve infrastructure linking India and Pakistan

Pakistan and India need to improve the infrastructure connecting the two countries. From extensive delays at the seaports to poor cross border road infrastructure in Kashmir, inadequate trade infrastructure is common to all routes connecting India and Pakistan.16 To relieve strain on existing connections the two countries could open up more border crossings. Ideally, these crossings would be built with Integrative Check Posts (ICP), similar to the existing one at Wagah in Punjab. The ICP is a 120 acre facility that significantly expanded the customs and inspection facilities on the India side of the Wagah-Attari border crossings,17 allowing trade traffic between India and Pakistan to increase from 100-150 trucks per day to about 250 trucks per day.1819

Indo-Pakistan Trade across the Line of Control in Kashmir20

At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that infrastructure improvements need to take place on both sides of the border to make them effective. Although the ICP at Wagah has increased processing capacity, no comparable improvement infrastructure has taken place on the Pakistani side of the Wagah crossing, and the true benefits of improved infrastructure will only be realized when improvements are implemented on both sides of the border. In addition to physical infrastructure, the two countries also need to build up banking and legal institutions. The virtual absence of these two components has made trade in Kashmir risky and difficult to accomplish. Building these vital linkages will ensure that future growth in Indo-Pakistan trade is sustainable.

4) Improve ties between the Indian and Pakistani business communities

India and Pakistan need to improve coordination between business communities on both sides of the border. The joint Chamber of Commerce in Kashmir was successful at linking the two business communities together, even though it has not been as successful as intended for its initial purpose of liberalizing cross-Line of Control trade.21 The governments of India and Pakistan need to expand these types of business oriented organizations in places like Punjab, Sindh and Gujarat.

Dried Date Merchant, Karachi, Pakistan22

Dubai, the UAE and other third party countries currently function as meeting grounds for the Indian and Pakistani business community. This is due to the fact that it is easier to travel to these third party countries than to go across the shared border. Additionally, Indo-Pakistan trade often flows through these indirect routes to circumvent the restrictive and often convoluted trade regulations across the Indo-Pakistani border. While India and Pakistan work to build better direct trade relations, they could engage members of the Pakistani and Indian business communities by establishing organizations to facilitate interaction between them. Eventually, as relations improve, these organizations could help expedite the shift of Indo-Pakistan trade back from these third party locations.

Conclusion

Imposing greater Indo-Pakistan trade solely through policy will not be sustainable in the long run. Rather, India and Pakistan must use policy to craft an environment where trade can freely occur. However, this trade will only be sustainable if there is greater cultural awareness between the people of the two countries. A prominent businessman from Kutch in Gujarat once asked me, “Why should we trade with those terrorists?” Only when Indians and Pakistanis break away from such false perceptions can trade truly evolve into a long-term road to lasting peace.

Ravi Patel is a student at Stanford University where he recently completed a B.S. in Biology and is currently pursuing an M.S. in Biology. He completed an undergraduate honors thesis on developing greater Indo-Pakistan trade under Sec. William Perry at the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC). Patel is the founder and president of a student to student collaborative research program connecting leading Pakistani and American university students and also the president of a similar organization called the Stanford U.S.-Russia Forum which connects university students in Russia and the United States. In the summer of 2012, Patel was a security scholar at the Federation of American Scientists. He also has extensive biomedical research experience focused on growing bone using mesenchymal stem cells through previous work at UCSF’s surgical research laboratory and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

A military depot in central Belarus has recently been upgraded with additional security perimeters and an access point that indicate it could be intended for housing Russian nuclear warheads for Belarus’ Russia-supplied Iskander missile launchers.

The Indian government announced yesterday that it had conducted the first flight test of its Agni-5 ballistic missile “with Multiple Independently Targetable Re-Entry Vehicle (MIRV) technology.

While many are rightly concerned about Russia’s development of new nuclear-capable systems, fears of substantial nuclear increase may be overblown.

Despite modernization of Russian nuclear forces and warnings about an increase of especially shorter-range non-strategic warheads, we do not yet see such an increase as far as open sources indicate.