CHAPTER III

THE FUTURE OF MARITIME ACTIVITIES

The maritime world of 20 years hence will be, for the most part, a much busier place. The forces and changes described in Chapter II not only will affect the types of activity occurring on the seas, but also will tend to increase the amount of maritime activity. The primary drivers of this increase in maritime activity will be the continued growth of the economic interdependence among states, the overall world population growth, the tremendous migration of people from developing states to developed states, and a projected significant increase in passenger carriers.

The oceans are vital to the overall growth of the world economy and population, and to the continued economic integration of nations. The oceans are a primary source of food, energy, and transportation, all key requirements of human activity in an interconnected world. Development of the oceans' natural resources and use of the oceans' highways for transport must increase to accommodate an ever-growing world.

Two primary challenges face the maritime states from now until 2020. First is the need to manage the growth in human use of the oceans with the need to protect the marine environment. Second is the substantial increase in illegal activity that will accompany the tremendous growth in legal maritime activity.

A. COMMERCIAL ACTIVITIES

1. Natural Resource Exploitation

"The oceans are no longer viewed by the community of nations as a vast unregulated void or solely as a barrier to be crossed. Not only must America exert its influence to safeguard its economic and security interests, we must support efforts to protect the seas and defuse conflict that arise from competing demands for the sea's resources. This can be achieved only through the development of a comprehensive agenda for the ocean in the 21st century.1"

John Dailey

a. Living Marine Resources

(1) Fishing Stocks. Worldwide demand for fish2 will increase through 2020, stressing already fully fished and overexploited stocks, reinforcing the need for sound fisheries management practices, and creating potential conflict among states competing for scarce fisheries resources. Marine fisheries production (the amount of fish caught, measured in tons) may increase to help meet the rising demand, but only through effective fisheries management. The United States faces both international and domestic challenges to ensure its fisheries remain sustainable.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) conservatively estimates that world demand for fish for human consumption will increase from 80 million tons in 1995 to 110-120 million tons in 2010.3 Fish are an important source of protein for much of the world's population. All of the regions around the globe are expected to have an increased demand for fish in the future, especially Asia. Aquaculture, or fish farming, will help meet this rising demand, but marine fisheries will still be the primary source.

This rise in world demand for fish will place increasing stress on fish stocks, many of which are already overexploited. Of the top 200 marine fish resources in the world, over 60 percent require urgent management of the fishery because they are overexploited or fully fished. In North America, for example, the once robust cod fishery off the northeast coast of Canada is under moratorium because of overexploitation, and in Europe many groundfish stocks have been exploited so intensely that they are considered outside safe biological limits.4

Despite current depletion of fisheries stocks, it is possible that stocks as a whole may recover and remain at sustainable levels by 2010 should effective fisheries management practices be enacted and enforced. Many states are already taking steps, and the international community as a whole has recognized the need for fisheries management, adopting measures such as the UN Agreement on Conservation and Management of Straddling Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish (Straddling Stocks Agreement). The significance of the Straddling Stocks Agreement is its recognition that current fishing levels cannot be sustained at current harvesting rates. Under the FAO's optimistic scenario, where fisheries management is improved, marine fisheries production will meet heavy worldwide demand for fish in 2010. Under the pessimistic scenario, where fisheries management is ineffective, marine fisheries production drops below current levels, far below the expected demand in 2010.5

There are three key components to the future success of worldwide fisheries management. All of these components will have to be used to some extent over the next two decades throughout the world.

(a) Reduction of fishing fleet size. Reducing fleet size by at least 30 percent is a first step required in protecting the world's fish stocks. Various plans to do this exist, such as retiring vessels, buying back permits, and limiting entry into a fishery as others' permits expire. The United States has just completed such an effort to reduce the size of the New England fleet. These efforts are less effective if capacity is simply transferred from one fishery to another, such as in places like Italy, China, and Taiwan, where conversion programs have allowed former high seas driftnetters to enter other fisheries.

|

|

|

Figure III-1. In order to protect fish

stocks, the size of the New England

fishing fleet was recently reduced.

|

(b) Reduction or elimination of subsidies. Several foreign governments subsidize fisheries at a worldwide cost of $10 billion annually, according to the United Nations.6 These subsidies encourage overcapitalization and greater effort by fishermen, and they increase consumer demand.7 Examples of subsidies include guaranteed low interest loans, subsidized commodity prices, and capital investment tax incentives.

(c) Limiting access. Today, fisheries managers are using several methods for limiting access to fisheries. One option, Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs), establish property rights to what had previously been a public asset. Total-allowable-catches are established and divided among several quotas. These quotas may be bought and sold as property. The advantage of ITQs over programs like "days at sea" limitations is that ITQs give fishermen a vested interest in protecting their resource since they are only allowed to fish up to their quotas. Under a "days at sea" program, fishermen are limited in how many days they can fish, but there are no restrictions on the amount of fish they can catch during those days. Other programs for limiting access include closing specific areas to fishing (or to a particular fishery) and restricting access to an area to certain permitted vessels. These two programs are currently in place on Georges Bank in the Gulf of Maine.

Full implementation of these measures worldwide will not be easy. These measures require the commitment of resources to compensate fishermen for their vessels and other capital removed from the business. They also require plans (and more resources) to help these displaced fishermen to earn a living in other sectors of the economy. Furthermore, in the face of escalating demand for fish, limiting access will require significant commitment to enforcing any restrictions on fishing. Enforcement will be required to ensure domestic fishermen are obeying restrictions and to protect fisheries from foreign exploitation.

International cooperation will be critical to the success of fisheries management endeavors. Fisheries issues are complex, and involve competing interests even among friendly states. Nearly 40 percent of the world's oceans are claimed as exclusive economic zones, and coastal states control almost 90 percent of the oceans' fish. One example of international cooperation is the ongoing multilateral conferences on establishing a mechanism for the conservation and management of highly migratory fish stocks in the Central and Western Pacific. The ambitious aim of the 23 countries involved is to manage highly migratory stocks over a 20 million square mile area, using tools such as a comprehensive registry of fishing vessels, a vessel monitoring system, and at-sea boardings of vessels whose countries are signatories to the eventual agreement.

Despite efforts at cooperation, however, international fishing disputes will be inevitable. Disagreements among coastal states and coastal state enforcement measures will likely lead to conflict, and even violence, as countries grapple with balancing the need for food with the need to sustain the resource. Conflicts already in evidence today will be more prevalent in 2020.

Fishing is such an important part of many coastal country economies that it often reaches into the social fabric of society. If the depletion of fishing stocks continues, we may well reach a point where security concerns over fishing rights approach the level of the concerns presently being dealt with in regard to water rights in the Middle East.8

For the United States, fisheries management and enforcement will be a major concern through 2020, both internationally and domestically. The U.S. commercial fishing fleet contributed nearly $50 billion to the economy in 1995.9The United States has the largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the world, and it contains an estimated 20 percent of the world's fishery resources. Should the United States be successful in managing its fisheries, U.S. waters will become even more attractive to foreign fishermen than they are today. In FY98, the U.S. Coast Guard detected 218 encroachments of the U.S. EEZ by foreign fishing vessels. That number will likely increase through the next 20 years because of overfishing in other areas of the world. For example, many fisheries in Asian waters are overexploited, or even depleted, while demand there is expected to increase substantially. The FAO notes that the East Asian region will probably have a high dependence on distant water fishing in the next decade to satisfy demand.10 Bountiful U.S. Pacific waters would be a lucrative target for Asian fishermen.

For U.S. fisheries to be attractive to foreign fishermen, however, there must first be effective fisheries management at home. Fish stocks in the United States will only be at sustainable levels in 2020 if adequate fisheries management tools are implemented and enforced. This will require short-term sacrifice (e.g., reducing the number of fishing vessels and limiting access to fisheries) in the fishing industry for long-term gain, and long-term devotion of resources by the government to fisheries management and enforcement programs.

(2) Endangered Species. The number of endangered marine species in U.S. waters likely will not increase by 2020, assuming adequate fisheries management programs are in place. Marine management is looking more and more to preserving ecosystems rather than individual species, broadening the scope and improving the efficiency of marine protection measures. Changes in abundance and distribution of one species affect the distribution of other species as well, and single species approaches are no longer adequate for modern fisheries management. Of the 174 stocks of marine mammals

|

Figure III-2. Protecting marine mammals will remain a

challenge through 2020.

|

and sea turtles, 42 are on the endangered species list or considered depleted over a significant portion of their range.11 By 2020, the number of endangered or depleted species will not appreciably increase, and will likely decrease.

Marine mammal populations within the U.S. exclusive economic zone are expected to remain at current levels or increase through 2020, dependent in large part on how well the United States succeeds in preserving ecosystems and managing fisheries (maintaining food sources, enforcing no-trawl zones in vicinity of stellar sea lion rookeries, etc.). Collisions with ships and entanglement with fishing gear will loom as an ever-present hazard for large mammals such as the right whale, whose number has dropped to nearly 300.

Given the high priority placed by the United States on protection of the marine environment, more marine preserves will likely be established through 2020. The priority of the National Marine Sanctuaries will continue to be the long-term protection of U.S. natural resources. More coastal areas (See Table III-1) are likely to be designated as National Marine Sanctuaries, largely due to increasing development of mineral, hydrocarbon, living marine and gravel resources.

|

CANDIDATE OFFSHORE AREA |

REASON |

|

Alaska |

Protect living marine resources' habitat |

|

California |

Pressure from Environmental & Recreational Groups |

|

Texas |

Protect areas from Gas & Oil Industry |

|

Louisiana |

Protect areas from Gas & Oil Industry |

|

Florida (East Coast) |

Pressure from Environmental & Recreational Groups |

|

Eastern/Mid-Atlantic States |

Pressure from Environmental & Recreational Groups |

Table III-1. Candidate Areas for New National Marine Sanctuaries. 12

b. Exploitation of Non-living Marine Resources

The rapidly growing and interdependent international community of 2020 increasingly will probe and exploit the oceans for minerals and energy to fuel its expanding economy. Increasing world demand, improving technology, and decreasing availability of some resources on shore will stimulate greater seafloor exploration and development. Furthermore, exploration, drilling, and mining operations will move farther offshore as new technology advances the ability to operate in deeper waters. Production from the ocean waters themselves, rich in mineral deposits and holding tremendous energy potential, may become commercially viable, at least in some regions. Consequently, intensive commercial operations on and under the sea, including along the U. S. coasts, will greatly increase by 2020, presenting new and greater challenges to both the protection of the ocean environment and the safety and security of the people operating in that environment.

(1) Ocean Minerals. The marine mineral industry will be substantially more robust by 2020. Currently, the industry is active in exploration offshore, but production is limited to a few commodities such as sand and diamonds. In the short term, prohibitive costs and environmental concerns will hinder significant industry expansion beyond exploration. However, technological advances derived from deepwater oil exploration and production and, in some cases, increasing mineral prices may make marine mining ventures in several minerals profitable. Dr. James Hein, an International Marine Minerals Society Executive Board member from the U.S. Geological Survey, believes ocean mining "could be a profitable commercial industry around the year 2020 to 2025, but new companies are starting to see huge profit potential, so it could be sooner."13

Diamond mining off the South African coast offers a clue to the future of marine mineral mining. The South African offshore diamond mines operate in depths of 100 meters, and are continuously moving to deeper waters, according to Dr. Charles Morgan of the University of Hawaii's Marine Minerals Technology Center. In fact, the marine mines have actually become more profitable than diamond mining on land. Diamond mining occurs off the Namibian coast as well, where it is a billion-dollar industry.14 Technology developed in sophisticated marine diamond mining operations may be applied to mining for other minerals as well, decreasing development costs.

|

Figure III-3. Sand along a New Jersey beach is

replenished to combat coastal erosion.

|

The most sought-after mineral commodity from the U.S. outer continental shelf during the next 20 years will continue to be sand and gravel.15 Offshore sand and gravel is used primarily for beach restoration, coastal protection, and construction material. Through 2020, the demand for offshore sand and gravel likely will increase as land supplies begin to diminish and storms continue to erode beaches. Moreover, recovery operations will move farther offshore to avoid damaging coastal areas. There are immense sand and gravel reserves on the outer continental shelf, with estimates of over 2 trillion cubic meters on the Atlantic shelf alone.16 Already, six large sand-dredging projects are operating on the outer continental shelf along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. 17

In addition to sand and gravel, the oceans surrounding the United States contain a wide variety of mineral resources. These minerals are found on the continental shelf, in ocean basins, or dissolved in ocean waters. In the U.S. EEZ, potential mining prospects include:

- Phosphate beds from North Carolina to northern Florida

- Titanium-rich heavy mineral sands from New Jersey to Florida

- Gold-bearing sand and gravel deposits off the Alaskan shore

- Barite deposits off Southern California

- Manganese offshore along the Southern California and Georgia coasts

- Cobalt and platinum-rich seabeds in the Hawaiian EEZ

- Gold offshore near Nome, Alaska.18

While marine mineral mining in U.S. waters is not currently active, these minerals could be exploited if price levels rise to the point where offshore operations become profitable. This is a realistic possibility, since mineral prices fluctuate and often move cyclically, depending on demand. In fact, relatively rich deposits of gold were recovered in the waters off Nome, Alaska, from 1986 to 1990, but operations halted when the venture became unprofitable because of declining gold prices.19 Should the price of particular minerals increase in the future, mining could resume in U.S. waters.

|  |

|

Figure III-4. Left: gas hydrate breaking free from the sea floor (photo by Charles Fisher). Right: irregular pieces of gas hydrate recovered from sediments in the Sea of Okhotsk, east of Sakalin Island. |

(2) Methane Hydrates. While vast deposits of methane hydrates in the U.S. EEZ could provide a significant source of energy, commercial exploitation by 2020 is questionable for two reasons. First, a safe and economically profitable technique must be designed to extract the gas. Second, there are still vast deposits of liquid land- and ocean-based methane (natural gas) available for extraction, much of it using existing technology. Even so, Japan has begun drilling an exploratory well for methane hydrate extraction, and the U.S. Department of Energy is researching the feasibility of methane hydrate as an energy source. Should these research and development efforts bring technological breakthroughs, deepwater methane hydrate extraction could become a burgeoning business by 2020.

Methane hydrate deposits are abundant in the U.S. EEZ, especially along the East Coast. There are immense amounts of methane hydrate, concentrated in frozen, ice-like gas hydrates within the top several hundred meters of sediment in deep water on the continental margins of the United States.20 Geologists differ widely on the actual amount of methane hydrate available, but a conservative estimate is that the amount beneath the sea floor could double all the known fossil fuel resources worldwide, both exploited and untapped.21

Recovering methane gas from beneath the ocean floor presents several safety and environmental challenges. First, methane gas is very unstable and can be dangerous to work with. Second, melting the crystals could destabilize regions of the ocean floor, thus collapsing any drilling rig built there.22 Finally, the natural venting of unburned methane, a potent greenhouse gas, to the atmosphere may contribute to global warming.23 Still, with conventional oil and gas production moving into progressively deeper waters in the Gulf of Mexico, the exploitation infrastructure is now in place in those geographic areas where large deposits of methane hydrates are located. This will spur serious research into the viability of methane hydrate as an energy source, and by 2020 may lead to solutions to the safety and environmental challenges posed by methane hydrate production at sea.

(3) Oil and Natural Gas Exploitation. Oil and natural gas exploitation within the U.S. EEZ will continue through 2020. This exploitation will be affected by two factors: continued government restriction and a push to deeper waters. A 1998 presidential directive under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, which limits offshore oil and natural gas development to the Gulf Coast and parts of Alaska through 2012, will continue to stem industry growth in most of the U.S. EEZ. Oil and natural gas developments in water depths greater than 1,000 feet, otherwise referred to as "deepwater" activities, will become an increasingly important part of future production in the few areas where drilling is permitted.

The U.S. Department of Energy forecasts indicate U.S. offshore oil production will increase through 2006 and then decline to current levels through 2020.24 The projected initial increase is a result of deepwater activities and technological advances. By 2020, offshore production will be characterized by wells located in deeper waters and, as it is today, will be focused in the Gulf of Mexico. Overall U.S. oil production will decline at an average annual rate of 1.1 percent through 2020,25 while the demand for petroleum products in the United States is projected to grow by an average annual rate of 1.2 percent.26 The resulting gap between rising demand and declining production will be satisfied with an increase in foreign imports.

|

|

|

Figure III-5. Oil and natural gas platforms will grow significantly in the Gulf of Mexico by 2020. |

The U.S. use of natural gas will increase significantly within the next 20 years in order to meet an increased demand for electricity and to offset a decline in the use of nuclear power. Projections for natural gas production through 2020 indicate an average annual growth rate of 1.5 percent.27 Natural gas consumption, however, is expected to increase at a slightly higher rate, 1.6 percent per year.28 Like the oil industry, the difference between domestic demand and supply will be met with increased foreign imports. Net natural gas imports are expected to grow from 12.4 percent of total gas consumption in 1996 to 15.2 percent in 2020.29 A majority of the imports will come from expanded pipeline growth between the United States and Canada. While most of the imports will come across land, some offshore imports are expected from locations such as Sable Island, Nova Scotia.30 Liquid natural gas (LNG) will continue to be another source of energy, although less significant.31 Even so, LNG shipments will remain a maritime safety concern.32

The greatest development in the oil and natural gas industries during the next 20 years will be the growth of deepwater activities in the Gulf of Mexico. The expectations are so high that the Minerals Management Service recently published a report entitled Deepwater in the Gulf of Mexico: America's New Frontier. According to the report, "favorable economics, the development of three-dimensional and subsalt geophysical technologies, the announcement of several deepwater discoveries, the development of new deepwater drilling and development technologies, the passage of the Deep Water Royalty Relief Act, and the opportunity to lease new prospects have all contributed to the revitalization of exploration and development in the Gulf of Mexico."33

Increased production in the Gulf of Mexico will be offset by reduced production in Alaska. Oil production in Alaska is expected to decline at an average annual rate of 4.3 percent through 2020. The decrease in Alaska's oil production will be driven by the continued decline in production from Prudhoe Bay, the largest producing field, which historically has produced over 60 percent of Alaskan oil.34

A moratorium on oil and gas development on the outer continental shelf will remain in effect at least through 2012, thereby limiting activity mainly to Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico. In June 1998, President Clinton issued a presidential directive under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, which extended the moratorium signed by President Bush to protect the coasts from the threat of oil spills.35 The moratorium prohibits oil and gas drilling and leasing on most of the U.S. outer continental shelf with the exception of the Gulf of Mexico and portions of Alaska. President Clinton's directive also added a permanent ban on oil and gas development in fragile marine sanctuaries.

Another environmental concern is oil transfer operations. Fears of large oil spills along fragile coastal areas, combined with increased imports by large tankers may raise pressure to force oil transfer operations offshore. However, the high cost of offshore oil transfer facilities will limit future progress. Developments such as the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP) have been only marginally successful. Despite the environmental benefits the LOOP offers by being so far from shore, it has not generated enough revenue to be profitable.36 The port of Corpus Christi, Texas, attempted a similar venture on a slightly smaller scale, but after analysis revealed it would take 20 to 25 years to break even, the project was halted.37 Future prospects for offshore port development are, therefore, considered unlikely.

|

|

|

Figure III-6 Ocean energy conversion is a potential energy source for some U.S. islands, such as Hawaii. |

(4) Ocean Energy. Harnessing ocean energy for commercial applications in the next 20 years likely will remain economically unfeasible for large-scale operations, but the potential for small-scale development does exist. Ocean energy does offer a significant source of energy supply, but unless other, currently cheaper sources of energy rapidly diminish, there is little incentive for any significant growth in the industry.

Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) is one energy conversion process with several applications. These include the following:

- generating electricity

- desalinating water

- supporting deep-water mariculture

- providing air-conditioning and refrigeration

- aiding mineral extraction.38

According to the Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, Colorado, the OTEC potential is enormous. "On an average day, 23 million square miles of tropical seas absorb an amount of solar radiation equal in heat content to about 250 billion barrels of oil. If less than one-tenth of one percent of this stored energy could be converted into electric power, it would supply more than 20 times the total amount of electricity consumed in the United States on any given day."39

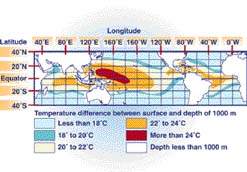

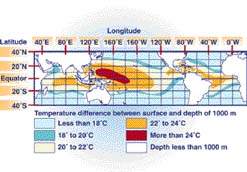

Figure III-7. Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion is possible where surface and deepwater temperature differences exceed 20 degrees Celsius.

OTEC is the process of converting solar radiation to electric power using the ocean's natural thermal gradient to drive a power-producing cycle. "Warm seawater from the ocean's surface and the cold deep water below are pumped through a surface and the cold deep water below are pumped through a heat exchanger that employs a working fluid, such as ammonia, propane, or freon, in a closed cycle. The warm water vaporizes the working fluid, which turns a turbine, thus producing energy."40 In order for OTEC plants to work properly, the warm surface temperature must differ by about 20 degrees Celsius from the cold deep water.41 Figure III-1 shows where the 20-degree difference can be found. In the United States, OTEC technology is focused on the Gulf of Mexico, Florida, and islands such as Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.42 OTEC facilities can be built on land, submerged on the continental shelf, or designed to float on the surface.

OTEC plants could be competitive during the next 5-10 years in three particular markets. However, OTEC competitiveness is highly dependent on other energy source prices. Potential OTEC markets include the following:

- Small, land-based plants producing electricity and desalinated water on Pacific islands.

- A larger land-based plant in Hawaii producing electricity and fresh water.

- Floating systems transmitting electricity to shore in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.43

The other two types of energy conversion, tidal and wave power, involve the mechanical motion of the ocean. All of the systems developed to capture mechanical energy are designed to supply electricity.44 Engineers in many countries have developed devices for generating electricity from tidal and wave power. Specially designed turbines mounted in dams or on moorings can capture the energy manifested in elevated sea levels or strong currents.45 These systems are ineffective, however, where tidal amplitudes are not high, currents are not strong, or wave conditions are inconsistent.

The growth in marine natural resource exploitation, particularly in the deepwater environment, will bring about new marine safety and security challenges in the years ahead. The year 2020 will likely see more oil and natural gas platforms in deeper waters, more pipelines offshore, increased ocean-based mining and dredging operations, and the possibility of ocean energy conversion facilities. Building, maintaining, and

|

|

|

Figure III-8. New challenges will emerge over the next 20 years with the development of deepwater platforms. |

servicing these capital projects will greatly expand the amount of vessel traffic and human activity on the seas. While there will be strict regulation of these activities in U.S. waters, regulation alone will not guarantee the safety and security of life at sea nor the preservation of the environment. Substantial monitoring, enforcement, and response capabilities will be required.

There will be significant growth in U.S. offshore oil and natural gas platforms and pipelines by 2020. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the number of oil and natural gas wells, both at sea and on land, is expected to increase between 0.7 and 2.2 percent per year, depending on oil price levels.46 The greatest growth of offshore platforms will occur on the outer continental shelf of the Gulf of Mexico where the innovative use of cost-saving technology and expected continuation of recent huge finds have encouraged greater interest.47 Increased oil and gas production in the Gulf will require more pipelines as well. Pipeline construction the Gulf of Mexico is expected to grow substantially since much of its existing pipeline infrastructure is at or near capacity.48

Figure III-9. Ruptured pipeline in Texas' San Jacinto River, 1995.

The growth in deepwater oil and gas infrastructure and operations will have major implications for maritime safety and security. Deepwater wells may be significantly more remote, increasing emergency response time. The operations may be technically more sophisticated and produce at much higher rates,49 increasing the scope of potential marine accidents, such as spills. Specific pipeline concerns include:

- Greater environmental risks associated with longer pipelines

- More complex oil-spill contingency plans required for larger pipelines.50

The growth of jobs in the deepwater commercial energy sector is another safety concern. More accidents at sea could occur as larger crews begin operating offshore. "Some analysts project that deepwater development in the Gulf of Mexico could create as many as 100,000 new jobs, with up to 70 percent of these sustained beyond 25 years."51 The response time in the event of an accident will increase as support structures and vessels begin operating farther from shore. The Minerals Management Service estimates that many of the new deepwater facilities will be beyond a 2-hour helicopter flight.52

In general, the safety and security concerns brought on by deepwater oil and gas exploitation can be applied to other marine industries as well. While the future for marine mineral mining, methane hydrate extraction, and ocean energy conversion is less certain, operations in any of these fields pose their own risks to the marine environment and place more lives at risk on the seas.

New technologies and larger, more complex facilities associated with deepwater activities could also create conflict ashore. Deepwater resource development will place increased demands on coastal ports and communities for support facilities and services.53 With an increasing number of entities seeking to exploit ocean resources, conflicts among users could arise. Currently, some communities are opposed to offshore development because of environmental and land-use concerns. Most likely, any deepwater development will be opposed by some environmental activist groups, who may protest ashore or at sea.

|

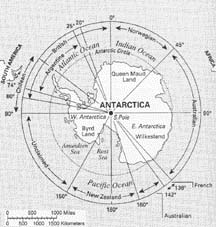

ANTARCTICA: A LOOK INTO THE FUTURE

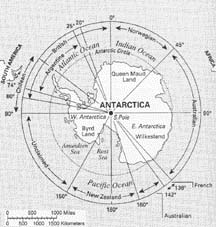

The international competition for Antarctica, for all practical purposes, ended in 1959 with the Antarctic Treaty. Its associated procedures and measures have successfully governed the Antarctic activities of nations for nearly 39 years.54 The treaty froze existing territorial claims, forbade new ones, banned military operations, and outlawed placement of nuclear weapons and disposal of radioactive wastes in Antarctica.

The 1980s and 1990s have witnessed a commitment to the Treaty system with the adoption of several improvements. Amendments in 1980 limited the exploitation of living marine resources and, in 1991, imposed a 50-year ban on mining. Antarctica will be protected further with the adoption of the Antarctic Environmental Protection Act of 1996 (ratified by the United States in 1997).55

As one of the most pristine and underdeveloped regions of the world, Antarctica's natural resources may draw attention as resources are fully exploited in other areas. The anticipated increase in commercial activity in Antarctica will be most notably in tourism and, because of ambiguities in the Treaty amendments and the lack of enforcement presence, harvesting of living marine resources. The number of cruise ships visiting the Antarctic region will increase profoundly through 2020.56 The sub-Antarctic seas have attracted the fishing industry as nations have closed off their EEZs. The fishing industry is practically non-regulated in this area, and overfishing has caused the near extinction of species such as the Patagonian toothfish (also known as Argentine Sea Bass). Another concern is the potential drilling for offshore oil deposits. The U.S. Geological Survey believes that oil will be the only mineral exploited in the next two to three decades, and then only if drilling technology suitable to the unique conditions of the Antarctic becomes available and market conditions make it economically attractive.57

|

Figure III-10. Territorial Claims in Antarctia58

2. Legal Maritime Trade and Activities

Whether transporting dry cargo, petroleum products, or people, ships will continue to provide a cost-effective mode of transportation well into the next century. The vast majority of all commodities moving by sea throughout the world will continue to consist of legal goods in lawful transit. Large container ships and high-speed ferries likely will have the most significant impact on maritime transportation in the foreseeable future. These developments along with several others will continue to pose maritime safety challenges for the United States. The challenges likely will intensify as seaborne trade triples by 2020.59

Significant trade growth is expected between the United States and Asia over the next 20 years. "The Clinton Administration predicts that nearly 75 percent of the world trade expansion over the next two decades will come from emerging economies. The economies to watch are China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Brunei, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and India."60 Brazil, India, and the Soviet successor states also will increase trade with the United States but not at the same level as Asia.61 Increased trade with these countries does not necessarily mean more ships, but rather larger ships carrying more cargo. Increased foreign trade also raises the potential for increases in smuggling of illegal goods hidden amongst legitimate cargo.62

|

|

|

Figure III-11. The Regina Maersk was the largest container ship to call at a North American port when it sailed into New York Harbor in July 1998. |

a. Container Shipping

The container shipping industry will undergo enormous growth through 2020, highlighted by larger ships carrying more cargo. Container ships are already growing in size, with the newest versions too large to enter most U.S. ports. These large container ships, sometimes referred to as mega-ships or super ships, are usually 4,500 TEU63 or larger and require 43-47 feet of water. Industry experts believe about one-third of the world's container ship fleet will be 4,500 TEU capacity and larger within 15 years.64 The REGINA MAERSK, 1,043 feet long with a 6,000-TEU cargo capacity and 47.5-foot draft, is just one example of the mega-ships that will transit U.S. waters in the future. The push toward larger container ships is being driven by profit considerations; simply, more containers aboard a vessel decreases the cost per container. Mega-ships primarily will visit a few major load centers, which can handle the ship size and cargo volume. As a result, feeder ships transiting from the load centers to smaller ports will increase coastal trade.65 An increase in coastal trade could mean more U.S.-flagged ships.

With the move toward huge container ships calling on a few major load centers, another possible development in the container industry will be the "Fast Ship" working between the load centers and feeder ports. In the "Fast Ship" scenario, smaller, 1200-TEU container ships traveling at speeds of up to 40 knots rapidly move containers to the feeder ports.66 The movement of these relatively large vessels at such high speeds could create safety concerns in the coastal shipping lanes.

b. Bulk and Break-bulk Cargo

While the growth in containerized cargo will have the greatest impact on future U.S. shipping trends, bulk and break-bulk cargo will remain extremely important through 2020. Bulk cargo vessels carry large quantities of cargo, such as grain or iron ore, in large, uncompartmented cargo holds. Break-bulk cargo vessels carry their shipments in barrels, bags, pallets, or other units. Bulk and break-bulk cargoes make up half of all cargo (by volume) entering or leaving the United States,67 and will continue to account for a large portion in 2020. Cargo freight rates for these vessels that operate in the Atlantic have remained relatively stable as demand for shipments between the United States and Europe has fluctuated. In the Pacific market, Asian economic difficulties and currency devaluations have greatly reduced the demand for cargo shipments from the United States to Asia, but the demand for shipments from Asia to the United States has actually increased. Generally, when one market slows down, excess vessels can be moved quickly into other markets. Thus the outlook for bulk and break-bulk cargo vessels should be stable for the foreseeable future.68 Bulk and break-bulk cargo will remain critically important in U.S. maritime trade, but because no major changes in this field are expected, the demands on port infrastructure, vessel safety, and law enforcement efforts, from this sector of the market, will remain relatively stable.

c. Tankers

Tanker traffic in U.S. waters will increase substantially by 2020 as U.S. oil imports rise. Increasing energy demand in the United States and decreasing domestic petroleum production will drive oil imports from 46 percent of U.S. petroleum consumption in 1996 to 66 percent in 2020.69 The demand for increased oil imports will be met with more transits rather than growth in tanker size.70 Domestically, Alaskan oil production will decrease, while oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico will move farther offshore. These trends will bring accompanying changes in tanker movement patterns. By 2020, more foreign tankers will be entering U.S. waters, especially the Gulf of Mexico. The Gulf will be the area of primary activity for two reasons. First, most of the U.S. oil refining capacity is in Gulf ports. Second, increased deepwater oil production in the Gulf likely will require tankers as well as pipelines to move oil ashore. On the West Coast, fewer U.S. tankers will be transiting from Alaska to refineries in Southern California, because of the drop in Alaskan oil production. However, there will be more foreign tankers bringing oil to West Coast refineries.

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports into the United States will continue through 2020, but not at significant levels. Although LNG shipments will only represent a small portion

|

|

|

Figure III-12. Nuclear waste being loaded for shipment. |

of U.S. energy imports, the volatile characteristics associated with LNG will present a significant safety concern during vessel transits. Two U.S. ports (Everett, Massachusetts and Lake Charles, Louisiana) likely will continue to import LNG through 2020.71 LNG imports into Everett and Lake Charles are projected to increase, reaching a level of 0.36 trillion cubic feet in 2020, compared with 0.04 trillion cubic feet in 1996.72

d. Nuclear Waste

The need to move and secure shipments of spent nuclear fuel and waste from reprocessing will increase. This trade is now predominately between the Far East and reprocessing facilities in Europe. Future concerns about an environmental catastrophe and security of the nuclear waste will lead to increased demands for storage in or transit through U.S. hands, particularly from the Russian Far East.73 At the same time, increased numbers of plants will generate a growing surplus of spent fuels to be transported.

e. Port Infrastructure

U.S. ports will face intensifying pressure to expand to meet the growing volume of shipping and to combat the threat of foreign competition. The container industry, in particular, because of the increasing volume of cargo and the growing size of the ships themselves, will divide ports into two categories: load centers and feeder ports. "The relentless introduction of large containerships into U.S. trades is dividing the port industry into two camps: an elite tier of large ports with deep harbors and excellent inland infrastructure, and a second tier of feeder ports that cannot accommodate the new generation of vessels."74

The ports that are able to expand and meet market demand will progress into load centers for the United States. Several factors, including harbor depth, efficiency in intermodal connections, labor productivity, and the size of the local market will influence a port's ability to develop as a load center.75

|

|

|

Figure III-13. Containerships will drive port development over the next 20 years. |

- Harbor depth. In order to be a successful load center, a port's waters likely will have to be at least 45 feet deep.76 Mega-ships such as the REGINA MAERSK will require deep channels to access port facilities in order to offload their enormous amount of container cargo.77 Ports that cannot dredge because of legal and environmental restrictions will be forced into the feeder port category.

- Intermodal efficiency. Load centers will require efficient terminals and inland infrastructure in order to move large volumes of cargo. Load centers will require superb railways, roadways, and inland waterways, and will need efficient, rapid means for moving high volumes of cargo from the dock to the secondary mode of transportation.

- Labor productivity. Ports will attract more customers if they can service ships quickly and thereby reduce the associated labor costs. The reliability and productivity of the labor force in a port will influence how favorably a port is viewed by the shipping industry.

- Local market. Large local markets stimulate intermodal connections, provide relatively fixed revenues, and reduce competition from other ports because of the proximity of the market to the port.78

|

|

|

Figure III-14. The of Long Beach is currently one of the busiest cargo container ports in the United States. |

Load centers will play an important maritime role as both mega-ships carrying large volumes of cargo and feeder ships conducting coastal trade travel the harbor waterways. Under pressure to develop into load centers, several ports are undertaking significant projects in order to meet future shipping needs. The success of these developments will become important in determining which ports evolve into load centers. The ports that do not evolve into load centers will become feeder ports. Feeder ports still will play an important role in maritime trade, even though they will not handle volumes of cargo nearly as large as those moved through the load centers.79 Unlike the load centers, feeder ports will be less affected by global developments in the shipping industry. These ports will strive to diversify into bulk and break-bulk trades to avoid dependence on the container industry. However, lower profit margins in bulk and break-bulk, and competition from other transportation modes (railroads, pipelines and canals/waterways), may prevent ship owners and operators from driving expensive capital development the way they can in the containerized sector.

While U.S. ports will compete among themselves for positions as load centers, their greatest competition may very well come from foreign ports. Vancouver, Halifax, and Freeport (Bahamas) already compete with American ports for U.S.-bound container cargo, and by 2020 Mexican ports could challenge as well, if improvements planned for the Mexican transportation infrastructure are completed. Halifax, where the main channel is 60 feet deep, has captured ten percent of New York's Midwest-bound traffic annually over the last four years.80 The deep harbor and intermodal infrastructure in Halifax make the port a strong competitor for eastern U.S. ports. The North American Free Trade Agreement further enhanced the competitiveness of Halifax and other non-U.S. North American ports, expanding their access to U.S. markets. While 98 percent by weight of all cargo leaving or entering the United States currently passes through U.S. ports,81 the challenge from foreign ports, particularly in containerized cargo, could reduce that figure.

f. Cruise Ships and Ferries

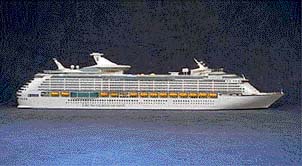

Tremendous growth in the cruise line industry and the emergence of high-speed ferries will be the key developments in the maritime passenger transport business through 2020. Both developments will pose challenges to maritime transportation in the United States.

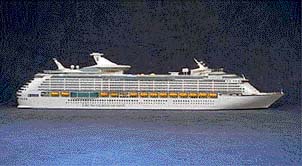

Figure III-15. Royal Caribbean's cruise ship, Voyager of the Seas, is under construction in Finland. The vessel will displace 142,000 - tons and span the length of three football fields.

The cruise line industry will exhibit strong growth throughout the next two decades. The average annual growth of the industry has been almost eight percent since 1980, and with the world fleet of 230 cruise ships operating at 90 percent capacity,82 there are no signs of this growth slowing. North America is the largest market, and surveys indicate that 56 percent of Americans want to take cruises, while only 11 percent have done so. The number of cruise line passengers worldwide is projected to triple to 15 million by 2020, according to one industry expert.83

The cruise line industry will respond to this increasing demand with new ships and new markets. The number of cruise ships will likely double before 2020; the industry already is building or has plans to build 44 ships. Many of these new ships will be larger as well, with behemoths such as the 142,000-ton VOYAGER OF THE SEAS coming on line within the next two years.84 The president of Carnival Cruise Lines believes the overriding trend in the worldwide cruise industry will be the significant increase in global capacity as older ships are retired from the North American arena.85 New cruise markets will emerge as these older vessels reposition to other areas. The Caribbean will remain the top destination of cruise ships, with approximately 60 percent of such traffic,86 but more routes will open to remote areas such as South Pacific islands, the Amazon, and Antarctica.

The particular factors involving U.S. policy could have a profound impact on the cruise industry in the next 20 years. First, Cuba will become a very popular destination if the U.S. embargo is lifted. A 1992 study found that half a million cruise passengers would likely visit Cuba in the first two years after the lifting of the embargo, followed by 1.2 million in the subsequent few years.87 Second, if the Passenger Service Act-which requires U.S. crew members on cruise ships transiting from one U.S. port to another U.S. port-is amended, there could be more cruises to destinations like Hawaii since cruise lines will be able to increase profits by hiring foreign laborers at lower wages.

Another maritime transportation industry expected to grow significantly by 2020 is the high-speed ferry business. In certain world markets, high-speed ferries are already competitive with other forms of transportation, particularly commuter airlines. High-speed passenger ferries already have begun to ply U.S. waters and will increase in number and speed over the next two decades.

Figure III-16. The Bay Ferries' Cat can reach speeds in excess of 50 knots making it the fastest car ferry in North America.

SeaConn is one emerging high-speed ferry company and is illustrative of the future high-speed ferry industry. SeaConn is creating a super high-speed passenger ferry system that connects Long Island, Connecticut, and New York City. These ferries will be the fastest in the world, significantly reducing the commute to and from New York and between Long Island and Connecticut. The SeaConn system will operate seven vessels, each 214 feet long and capable of speeds in excess of 60 knots. 88

Ferries, such as those employed in the SeaConn system, will pose significant safety challenges as they encounter other maritime traffic. The potential for mishaps will grow as technology increases ferry speeds. Some experts are predicting high-speed ferries could reach speeds up to 80 or even 100 knots as they strive to compete with other forms of transportation.89 The challenge will be to maintain adequate separation between these high-speed ferries and other vessels, thereby reducing the risk of human error.90

g. Underwater Cables

The undersea cable industry is expected to grow considerably through 2020 as the fiber-optic cables industry strives to compete against satellite communications. Growth in undersea cable investments between 1997 and 1998 increased by 81 percent demonstrating a strong resurgence in the undersea cable market.91 Several companies are involved in building extensive fiber optic networks to support the future cyber world. As a result of these vast cable networks, new infrastructure for cable repair and maintenance will be required for support.

Figure III-17. More cable ships will be required to sustain the growing fiber optic cable industry over the next 20 years.

Two projects under development help paint a picture of what the future will hold. "Project Oxygen is an ambitious initiative to lay 320,000 km of mainly undersea fiber optic cable, with 262 landing points in 175 countries and locations to produce a US $14 billion `Super-Internet.'"92 The cable maintenance for Project Oxygen will ultimately be performed by 23 cable ships.93 Global Crossing Ltd. is building a similar undersea cable network which will directly connect Asia, North America, Europe, Central America, and the Caribbean.94 As the size and scope of the undersea cable industry expands rapidly, the infrastructure necessary to support cable repair and maintenance will increase accordingly. The recent and projected growth of the cable industry represents a significant resurgence, which could grow considerably during the next twenty years if initial networks prove successful.

3. Illegal Maritime Trade and Activities

A drawback of increasing maritime trade, and economic globalization in general, is that it will facilitate the expansion of transnational crime. Trafficking in drugs, arms, and people is already big business, with maritime means a key method of transport. These transnational crimes will not disappear by 2020, and may, in fact, increase. The corrupting influence of the organized crime groups controlling these activities will threaten the safety of peoples and the security of governments. The ability of these organized crime groups to form alliances and easily permeate international borders in 2020 will intensify their threat to the state.

a. Drugs/Narcotics

Control of the processing and sale of illicit drugs worldwide is a continuous challenge that has no short-term solutions.95 The United States has wrestled with drug control since the 1930s when the Federal Bureau of Narcotics was first established. Since then, increasingly rigorous anti-drug programs have failed to keep the U.S. population from becoming the world's greatest illicit drug consumer.96 The U.S. General Accounting Office estimates that law enforcement, corrections, and public health costs of the illegal drug problem total $67 billion annually.97 Despite U.S. and foreign efforts, to date, no solution to the Gordian knot of drug control has emerged.

There is little evidence to suggest this complex problem will be solved by 2020. Given that there likely will be a future illicit drug market, there also will be sources of supply and transportation methods to deliver drugs to market; the maritime trafficking of illegal drugs is expected to remain a global threat.

(1) The illicit drug market.

Assessing the worldwide future demand for illicit drugs is difficult. While profit is the central motive in the decision to sell illegal drugs, motives for using drugs can vary greatly. Societal and cultural mores provide a starting point from which a nation's children begin making decisions about the seemliness of drug use. Since attitudes formed early tend to stay with one throughout life, teen opinions and attitudes about drug use are an important predictor of what a future market may look like.

In the United States, teen perceptions concerning drug use are mixed, but it is clear there is a teen drug problem. Almost one out of every ten teenagers and one in four twelfth graders use illegal drugs.98 Although current levels are fairly low, there has recently been a significant increase in teen use of heroin.99, 100 While most teens view cocaine and heroin use as risky or dangerous, they nevertheless are experimenting with these drugs at an increasingly younger age. Despite current efforts, the total amount of hardcore cocaine users in the United States has remained relatively constant.101 Hardcore users consume three quarters of the total cocaine consumed in the United States.102 As for marijuana, teens perceive it as a less dangerous drug.

While these facts do not lend themselves to any specific conclusions concerning the scope of the U.S. drug market in 2020, they do suggest that:

- By 2020, there will be an illegal drug market comprised of adults who habitually used drugs as teens in the late nineties.

These adults will have greater access to drugs primarily due to an increase in disposable income from full-time jobs.

- The number of chronic cocaine users will not significantly change.

The number of chronic cocaine users has not significantly changed in seven years. Given that any program attempting to alter perceptions of drug use will require time to take effect, (reversing perceptions of tobacco use took 20 years) the number of chronic users will not be significantly altered by 2020.

- Cocaine market demand will not significantly change

. Given that chronic users account for three-quarters of the total cocaine market, the number of chronic users is unlikely to change significantly by 2020.

- The global use of illicit drugs may increase if social mores change significantly.

Such changes could develop as a result of improved methods of drug ingestion, revived attempts to legalize controlled drugs, greater concern over personal freedoms, the lax enforcement of current drug laws, or a general global acceptance of drug abuse as an uncontrollable issue.

|

|

|

Figure III-18. New drug producing countries will emerge in 2020. |

While the popularity of certain drugs waxes and wanes, the United States, in general, has a large appetite for illegal substances. This appetite sometimes manifests itself in attempts to legalize certain drugs, especially drugs not considered "dangerous." Therefore, attempts to legalize marijuana have occurred regularly during the last twenty years, but there has been little effort to legalize other controlled drugs such as cocaine and heroin. Public perceptions of these drugs as "dangerous" will likely keep them confined to the U.S. Controlled Substances Schedule. In the unlikely event that marijuana is eventually legalized, enforcement officers will still need to be vigilant against traffickers importing other dangerous drugs.

(2) Illicit drug sources.

Worldwide illegal drug production is expected to continue to expand well into 2020. Illegal drug producers will be increasingly flexible in circumventing international enforcement efforts. They will be able to weather law enforcement attacks on specific drug production nodes and survive. This flexibility will be largely due to an increased use of technology to support highly mobile operations and to improve both operational security and production methods. Organized crime syndicates will provide effective business planning and will make use of their significant financial power to corrupt the authorities in a growing number of countries. The financial power of the cocaine industry in Latin America, for example, is staggering; cocaine is Latin America's second largest export, accounting for 8 percent of the GDP of Colombia, and 3-4 percent of that of Peru and Bolivia.103

It is not surprising that during the past decade, illicit drug production has spread to places where law enforcement poses the least threat.104 By 2020 major drug producing nations such as Afghanistan (heroin), Colombia (cocaine, heroin), and Mexico (marijuana, heroin and synthetic drugs), will likely be competing with other countries to supply major U.S. and European markets. Countries most vulnerable to being overwhelmed by drug producers are those that have weak central governments, access to regional or global drug markets, and remote areas where illegal drugs can be cultivated without detection. These conditions exist in many Eurasian countries of the former Soviet-bloc,105, 106 as well as some developing African nations.107 With the drug trade's significant profit potential, several of these countries will likely fall into the ranks of those where drug production is already endemic. 108

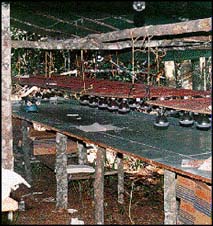

Future producers will use technology at least as efficiently as today's narco-businessman. Tools such as portable computers, handheld satellite phones, and increasingly "miniaturized" equipment make highly mobile production facilities an easily attainable goal. Where mobility is not required, producers can use technology to reduce operating expenses. Large-scale cannabis growers use computer-controlled, warehouse-sized hydroponics hot houses to grow thousands of plants in optimum growth conditions.109 With computers controlling water, plant food, light, and heat, fewer people are required, decreasing labor costs and improving operational security. Other improvements in the technical process have increased plant yields in both coca leaves and marijuana. In Colombia, chemical process improvements have yielded higher purity heroin than that of rival producers in Mexico. In the future, technology may allow producers to further increase plant yields, cheaply produce synthetic versions of organic drug components, or even mask indicators of drug use.

|

|

|

Figure III-19. Technology will improve drug production capabilities in 2020. |

While technology may significantly improve raw production capabilities, organized crime will provide many producers the business acumen, political leverage, and funds with which to effectively expand their enterprise. High-profit potential will continue to attract crime syndicates to the drug production business in 2020.110 For producers, the diversification these partners bring could provide ready-made distribution networks, money laundering services, and even venture capital, which could be used to purchase and incorporate new technology. This union of complimentary criminal enterprises inextricably links the drug trade to a host of other crimes such as smuggling (drugs, weapons, people) gambling, prostitution, and corruption.111, 112

(3) Illicit drug movement.

Drug trafficking will continue to plague the global community well into 2020. Future traffickers will increasingly rely on commercial transportation systems to move their products.113 The relatively low cost of maritime bulk transshipment and good product security, as well as limited personal risk, will entice a number of future drug transporters away from traditional non-commercial maritime methods. Smugglers moving smaller loads by speedboat will have more capable platforms than vessels currently in use, and future amateur smugglers will be able to effectively use traditional smuggling techniques with some degree of success.

Commercial maritime trade overall is expected to triple by 2020. A global trend in trade deregulation is largely responsible for this jump in international cargo movement. With the soaring of container shipping, regional transportation systems are increasingly becoming intermodal.114 International trading blocs are connecting their container moving systems (road, rail, and sea) together to allow for easy cargo passage through international boundaries. In addition to offering future drug transporters simplicity and convenience for shipping their product, the sheer volume of cargo being shipped via this method ensures no one specific shipment will be scrutinized too carefully. This method is certainly the most cost effective.

For smugglers moving smaller loads, traditional speedboats or "go-fasts"115 will likely continue to improve beyond today's impressive standards. Current fast boats used for smuggling can carry a metric ton of drugs at speeds of 35 knots or more and are very difficult to detect.116 Future boats may triple the speed and cargo capacity of current platforms, while virtually "disappearing" from law enforcement sensors through the use of a variety of low-observable technologies. Innovations such as super efficient engines or jet drives may significantly increase their operating range, and new computers may allow for the remote operation of high-speed delivery vehicles from an airplane or remote site.

|

Figure III-21. The capabilities of speedboats will likely improve the ability to transport drugs in 2020. |

Notwithstanding future technological improvements in drug detection, the resolve of anti-drug forces and the varying levels of political will to combat drug trafficking, future smugglers likely will be able to engage in their trade using methods and equipment common today. Despite current law enforcement's growing capability to counter smuggling, traffickers continue to reap enviable profits even with 25-30 percent load losses. This "cost" of doing business is one example of the typical smuggler's flexibility using conventional methods. Traffickers will continue to exploit gaps in law enforcement capability as well as legal and political impediments to international enforcement efforts.

(4) International resolve.

Absent a dynamic change in international cooperation and domestic resolve to substantially reduce illegal drug availability, the impediments to tomorrow's counterdrug forces will continue to be political, jurisdictional, and sovereignty issues which blunt effective drug control.

Effective regional drug control plans hinge on international cooperation, and future plans will require extensive collaboration among regional partners. International commitment and governmental resolve will be critical to any plan which might require the softening of sovereignty claims, cooperation with historically hostile states, and the commitment of resources such as defense forces and national police.

This level of resolve, while difficult to achieve, will be necessary if the world's nations are to deny illegal drug producers' and traffickers' exploitable niches. These niches extend beyond sovereignty concerns and constitutional interpretations, and are more complex than simply stopping drug boats. Drug producers rely on a business infrastructure to support their trade. Future enforcement efforts will need to exert greater pressure on key business nodes such as:

- Crop production

- Facility Security (insurgents, guerillas, and militias)

- Communications and Operational Security

- Transportation

- Chemical reagents for processing

- Cash Flow (money laundering/cash transportation).

The removal of any piece of this critical infrastructure would cause a significant disruption in the production or transportation of illegal drugs.

The simple removal of a drug production business node seems like an easy solution, but disruption even in one country is a difficult task. Even if this goal is achieved, the current global demand for illegal drugs is so massive that producers will remain intent on overcoming production obstacles with new methods or by moving production to another exploitable country. Although future drug control programs will need to develop and then emphasize demand reduction strategies, the interdiction of drugs at sea will remain a major tenet in reducing the available drug supply.

b. Arms Proliferation

Weapons will continue to be in high demand in 2020 throughout the world. Violence and open conflict resulting from ethnic or religious differences, nationalism, class struggle, criminal activity, or competition for resources will be constant threats, and may destabilize individual countries or entire regions. The various groups involved in these conflicts will often desire arms to help obtain their goals by force, if necessary, ensuring a thriving illicit arms trafficking business in 2020.

A large part of the illicit arms market will consist of small arms and light weapons ranging from handguns to shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles. Such weapons are easier to conceal and therefore easier to smuggle, and forces and groups armed with such weapons can cause damage and casualties disproportionate to their numbers. In some cases, irregulars can use such weapons to avoid defeat by . or even achieve victory against . the most modern and powerful military forces. In the recent past, for example, the Chechens fought the Russian Army to a standstill, and Somali clans weathered an intervention by modern Western forces. Bosnia-Herzegovina, Chechnya, the Mexican state of Chiapas, Colombia, Kosovo, Liberia, Rwanda, Somalia, and Zaire/Congo are just a few of the places where conflicts involving irregular forces fielded by insurgents or tribal groups and armed primarily with light weapons have captured media attention since the early 1990s.117

According to the Federation of American Scientists, "there are more than thirty wars raging in countries around the world today. These wars are being fought primarily with light weapons and small arms.Few combatants involved produce any, let alone the bulk of these munitions. Most light arms being used in these conflicts are imported - either through legal international channels, or through the black market."118

|

|

|

Figure III-22. Small arms

support criminals, terrorists, insurgents, and other groups. |

The demonstrated need for and effectiveness of small arms and light weapons will fuel a continued black market through and beyond 2020. Trafficked weapons will include both newly manufactured ones and older weapons drawn from arms caches maintained by stateless organizations or sold and transferred from the inventories of states. A portion of the arms traded on the black market inevitably will move by sea. In the United States, the greatest maritime challenge with respect to small arms and light weapons is and will remain their illegal exportation; overseas, the illicit arms market will operate worldwide.

(1) The market for small arms/light weapons.

The low cost of small arms and light weapons in comparison to heavy weaponry increasingly will attract new buyers.

In South America, for example, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Spanish language abbreviation FARC) and the National Liberation Army (Spanish language abbreviation ELN) have been engaged in a bloody conflict with the Colombian government for decades. In Colombia, paramilitary and insurgent forces use small arms and light weapons to conduct political assassinations and intimidation. "Violence is that country's leading cause of death. With a record 25,100 violent deaths in 1992, Colombia's murder rate is approximately nine times that of the United States."119

In addition to its importance to insurgents, the illicit small arms market is closely linked with drug dealers and other criminal groups and is growing as these elements work together to move illicit substances throughout the world. The lucrative business of smuggling small arms and light weapons, often in close connection with drugs, will remain a significant driving force behind small arms smuggling in the years ahead. In some cases, profits from drug trafficking provide the funds that insurgents need to purchase weapons.

|

|

|

Figure III-23. VS SS1 Rifles. |

In 1998, Russian organized crime groups reportedly exchanged weapons from their vast arsenal for Colombian drugs. Since the Russian crime syndicates can provide sophisticated weapons and new drug markets, alliances between Russian and South and Central American crime groups will remain likely. In Mexico, gun running is the third richest source of profit after drug trafficking and robbery/extortion.120 The growing number of small arms, which are smuggled to support organized crime and narcotrafficking, will allow drug cartels to resist government crackdowns violently and ultimately enhance their ability to smuggle drugs into the United States.121

(2) Sources of small/light weapons. Both new and old small arms and light weapons will emanate from a variety of sources, including the United States. Arms caches from civil wars and military armories sold on the black market will contribute to the growing diffusion of small arms and light weapons in the years ahead.

Small arms smuggled out of the United States will be among those available on the black market, and stopping that smuggling will a present a significant challenge to U.S. law enforcement agencies. U.S. arms manufacturers produce approximately five to six million weapons each year.122 Some of these weapons are smuggled into Mexico where an enormous small arms market exists. "Proximity, liberal gun sale laws, and inadequate law enforcement have made the U.S. Mexico's leading source of black market arms . despite Mexico's own strict gun control policy," according to the Federation of American Scientists.123 Weapons originating from the United States and illegally entering Central America via Mexico have fueled high crime rates in the region. The Inter-American Development Bank estimates that 120,000 people are murdered every year in Latin America, many by criminals, terrorists, and insurgents wielding U.S.- made firearms.124

In addition to those newly manufactured in the United States and smuggled overseas, small arms and light weapons already in circulation will continue to sustain the black market. Many of the weapons in circulation in the late 1990s date back to Soviet and American arms transfers to Central America in the 1970s and 1980s.125 In addition, U.S. weaponry abandoned in Vietnam in the early 1970s was smuggled to insurgent movements in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and other Central American states in the early 1980s. The enormous number of small arms that supported the civil wars in Central and South America in the 1980s remain in circulation on the black market. In the wake of the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, the 15 Soviet successor states, faced with severe economic challenges, will become increasingly willing to auction off ex-Soviet military hardware to the highest bidders.126 Ex-Soviet military equipment, therefore, will remain available, if not become more common, on the black market.

(3) Small arms/light weapons smuggling.

Smugglers will continue to transport illicit small arms and light weapons by sea through and beyond 2020. Despite occasional seizures of illegal weapon shipments, the full extent of maritime arms smuggling is unknown; identifying illicit arms shipments will become increasingly difficult as the volume of commercial seaborne trade triples by 2020.

Maritime arms smuggling will remain attractive because it allows smugglers to move large amounts of weaponry among legitimate cargo and within the legitimate transportation infrastructure. In a complex 1989 case, the Colombian police seized 232 Israeli-made Galil assault rifles after conducting a raid on one of the top leaders of the Medellin drug cartel. An investigation revealed the weapons were originally part of a larger arms shipment from Israel to the Caribbean nation of Antigua and Barbuda. The smuggling scheme involved Israelis, Antiguans, Panamanians, and Colombians who attempted to use legitimate covers to divert weapons to the Medellin drug cartel. The operation began in March 1989 when 500 assault rifles and ammunition left Haifa, Israel, aboard the motor vessel ELSE THUESEN bound for Central and South America via Antigua. While in Antigua, the container, presumably filled with weapons, was transferred to the motor vessel SEAPOINT which was supposedly bound for Panama. En route to Panama from Antigua, however, SEAPOINT, diverted to Santa Marta, Colombia, where the Medellin cartel took possession of the weapons.127

Smugglers also will use the United States as a transshipment point for moving weapons hidden among legitimate cargo, as they have done in the past. In one case "two Lithuanian nationals were arrested after they allegedly tried to sell Russian shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles for $330,000 to US agents posing as [Colombian] drug dealers. They were to be shipped through Bulgaria, Puerto Rico, and Miami."128 Another case, the largest in U.S. history, caught significant attention when U.S. military weapons left over from the Vietnam War era were shipped through the Port of Long Beach, California, in two large, sealed containers. "Before the arms returned home, they were well-traveled, having gone from Ho Chi Minh City to Singapore to Bremerhaven, Germany, through the Panama Canal, and up to Long Beach."129 The containers were filled with thousands of grenade launchers and M2 carbine parts and were never inspected by U.S. Customs while in the Port of Long Beach because they were not destined for the United States. Moreover, the cargo was represented as "hand tools and strap hangers." The containers were then placed on a truck and transported to the Mexican border where the arms were discovered by chance.130 Although it is unknown how often arms are smuggled through the United States, it is reasonable to suspect organized crime will continue to take advantage of trade deregulation and legitimate commercial infrastructure to move illicit arms to their final destination.

Smugglers will attempt to transport weapons manufactured in the United States to Central and South America. A majority of these weapons first move into Mexico, primarily carried overland by human "mules" or by commercial air.131 However, maritime smuggling represents another alternative for moving weapons from the United States to Central America. No substantial data exist on the number of weapons illegally exported from the United States via maritime means, but a report prepared by Mexico's Attorney General's Office, "cites flourishing gun/drug routes along the Pacific coast, the Gulf coast, and Central Baja and adds that a `significant' amount of arms trafficking originates out of central Florida, crossing through the Caribbean and entering Mexico through the Yucatan Peninsula."132 In the future, maritime smuggling via these routes likely will expand if U.S.-Mexican border inspections intensify to stem the overland flow of illicit weapons and substances.

In summary, the demand for small arms and light weapons will not diminish through at least 2020, and will continue to drive the black market and associated smuggling activities that transport them. While some of the weapons will move across land or by air, many will be transported via maritime means. These shipments will be difficult to detect, especially those shipped among legitimate cargo by the large smuggling operations that exploit the legitimate transportation infrastructure. Small arms will continue to be used by rogue states, insurgents, terrorists, and criminal organizations, any of which can threaten the ability of international organizations and national governments to maintain stability. Interdiction and prevention of illicit small arms and light weapons will continue to present a significant challenge to both U.S. and foreign law enforcement agencies.

c. Unlawful Migrant Entry Methods

With emigration pressure from less developed countries133 expected to rise over the next 20 years,134 thousands of potential immigrants will be unable to gain legal admission to the United States because of quota-controls, travel costs, or other obstacles. For a variety of reasons, many of these migrants will attempt to enter the United States illegally, and, with more than 12,000 miles of U.S. coastline, many of these attempts will be by maritime means. While some migrants will make these attempts on their own or en masse, others will receive assistance from family, friends, or paid smugglers to avoid detection and capture by border control forces.

Figure III-24. U.S. Coast Guard forces escorting

a Chinese migrant smuggling vessel.