Nuclear Plan Shows Cuts and Massive Investments

The Obama administration’s first nuclear weapons stockpile management plan is ready

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has sent Congress the FY 2011 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) with new information about what the administration plans to spend on maintaining and modernizing nuclear weapons and facilities over the next 15-20 years.

FAS and UCS got hold of the unclassified sections of the plan and have analyzed what the Obama administration’s first nuclear weapons management plan tells us about how the Prague speech vision will be translated into national nuclear weapons policy. The SSMP consists of five sections (three are unclassified):

- FY 2011 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan Summary (unclassified)

- Annex A – FY 2011 Stockpile Stewardship Plan (unclassified)

- Annex B – FY 2011 Stockpile Management Plan (classified)

- Annex C – FY 2011 Science, Technology, and Engineering Report on Stockpile Stewardship Criteria and Assessment of Stockpile Stewardship Program (classified), and

- Annex D – FY 2011 Biennial Plan and Budget Assessment on the Modernization and Refurbishment of the Nuclear Security Complex (unclassified)

Smaller Nuclear Stockpile Planned

The good news is that plan shows that the United States intends to reduce the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile by 30 to 40 percent from today’s total of approximately 5,000 weapons to 3,000-3,500 weapons at least by 2022.

Initiatives already underway from the previous administration are currently reducing the arsenal to some 4,700 weapons by the end of 2012, and the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) released in April will likely result in additional reserve weapons being retired.

The “3,000 to 3,500 active, logistic spare, and reserve warheads” would be the largest stockpile that could be supported by the weapons industrial complex proposed by the new plan, and about twice the size of the New START treaty limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads (note that the stockpile also contains non-strategic and non-deployed warheads).

Massive Investments Forecast

The reduction comes at a considerable price. To support the stockpile, the NNSA intends to spend more than $175 billion (in then-year dollars) over the next two decades on building new nuclear weapons factories, testing and simulation facilities, and modernizing and extending the life of the nuclear weapons in the stockpile.

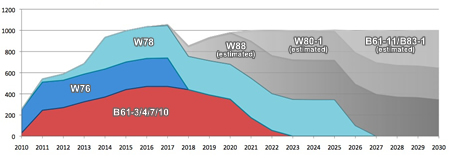

The plan shows for the first time how much will be spent on modernizing and extending the life of three nuclear weapons: the B61 gravity bomb, the W76 sea-based strategic warhead, and the W78 land-based strategic warhead. The cost is approximately $10 billion (in then-year dollars) between 2010 and 2025, peaking at about $1.05 billion in 2017 (at about the same time the New START strategic arms reduction treaty enters into force). Additional costs will follow as the remaining warheads in the stockpile are modernized and life-extended, projected at $1 billion per year in 2021-2030 (in then-year dollars).

.

The plan does not include the more than $100 billion the Department of Defense is expected to spend in 2010-2030 on the platforms needed to deliver the warheads. This includes a new class of ballistic missile submarines (estimated at $80 billion-plus), a new long-range bomber (presumably with a new cruise missile), and a new tactical fighter-bomber. (See latest Nuclear Notebook on US forces)

Smaller Stockpile, Expensive Complex

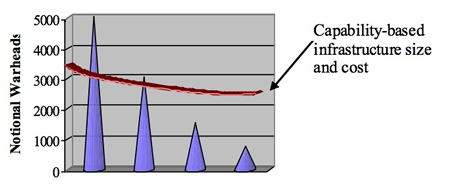

One of the more interesting parts of the plan is NNSA’s claim that even a much smaller nuclear weapons stockpile “would not lead to a smaller, less costly infrastructure” than the one proposed. In fact, NNSA concludes, “the costs to maintain capabilities necessary to support the stockpile are essentially independent of the size of the stockpile.” (Emphasis added)

| NNSA Stockpile-Complex Cost Matrix

|

|

| The NNSA plan suggests that the infrastructure needed to support a stockpile of less than 1,000 warheads will be about the same size and cost about as much money as the infrastructure needed to support a stockpile of 3,500 warheads.

|

.

According to NNSA’s calculations, even for a nuclear weapons stockpile of about 500 weapons, the size and cost of the infrastructure would be essential the same as what NNSA says is needed for a stockpile of 3,000-3,500 weapons. “After achieving a capability-based infrastructure, smaller total stockpiles than prescribed by post-NPR implementation strategies would not lead to a smaller, less costly infrastructure.” The basis for the argument is that even with 500 weapons, maintaining them would, in NNSA’s assessment, involve the same basic work and facilities as with the larger stockpile.

It is not uncommon to hear claims that proposed funding is the absolute minimum possible, but this claim will demand a lot of scrutiny in the months and years ahead. It implies that today’s complex maintaining 5,000 weapons would be about the same size and cost as the complex needed to maintain 8,000 weapons, which of course is not the case.

“New” Weapons or Just New Weapons

| New Capabilities Planned

|

|

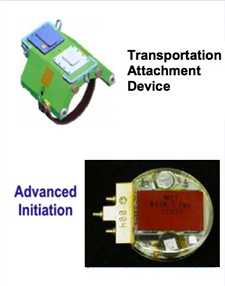

| The NNSA plan includes new capabilities, such as Arming, Fuzing & Firing (AF&AF) for all the warheads in the stockpile

|

The plan echoes the NPR’s promise that the United States will not build “new” nuclear weapons, but it shows that there are plenty of modernization options short of “new.”

Until a few years ago, the United States did not have the capacity to build new nuclear weapons. Since then, however, production of new W88 warheads has restarted and “war reserve” W88s are now entering the stockpile to replace those destroyed in surveillance tests. Other warhead types will follow in the years to come. The SSMP includes plans for building new nuclear weapons production facilities to ramp up warhead production capacity from 20 per year today to 80 per year by 2022.

The planned W78 modernization is described as “the next reentry system,” and the NNSA plan states that modernizing the complex will ensure that “the development cycle of future weapons is compressed.”

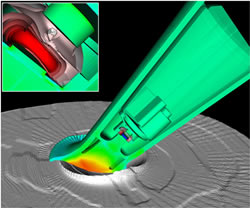

The plan strongly commits to continuing “current weapon alterations and modifications” and for adding “alterations/modifications to the enduring stockpile (or future strategic systems).” This includes advanced designs to “enable vastly improved capabilities for next system arming, fuzing, and firing [AF&F] and/or radar componentry….”

AF&F and radar systems are not part of the nuclear explosive package and therefore not normally considered covered by the pledge not to improve military capabilities of nuclear warheads. But “vastly improved capabilities” for AF&F and radar systems can significantly improve the military capabilities of a weapon and change the scenarios in which it can be used. One example is the new AF&F installed on the W76-1 during the current life-extension program, which adds new height of burst settings that increase the type of facilities the weapon can be used against. Another example is the B61-11 introduced in 1997, which is a modified B61-7 but with significantly different military capabilities.

Safety and Security as Modernization Drivers

Another category of warhead modernizations described in the plan involves the addition of new safety and security features to existing (and future) warheads. The demand for increased surety, as safety and security are jointly called, was triggered by the terrorist attacks in 2001 and has resulted in the pursuit of what the NNSA plan describes as “effective, affordable use denial options that address 21st century threats.”

| Safety and Security Pursuit

|

|

| Additional nuclear surety capabilities have become important divers for warhead modernization: all warheads will get some

|

It is not clear why the requirement for new surety features has increased, much less how much is needed. The same weapons were deployed before 2001 without any problems, but NNSA states that the new surety features are being pursued “independent of any threat scenario.”

In the near-term, the development focuses on new power management systems, security sensors, and integrated surety solutions such as advanced internal/external use-denial technologies. Warheads refurbished after 2010 will get new stronglink concepts, optical firing sets, and detonator safing. Longer-term developments include “multi-point safety for future insertion opportunities,” a capability that can significantly affect the nuclear package.

Most people obviously see nuclear weapons safety and security as important, but the addition of new features will gradually bring modified life-extended warheads further from their tested design. Since this could lead to demands for warhead replacements or even testing in the future, and given “the high cost and long time frame associated with integrating, qualifying, and certifying deeply buried subsystems through the LEP process,” a cost-benefit assessment is needed to create a benchmark for how much surety is enough.

And it is important to remember that nuclear weapons surety is not only a matter of what adversaries might do. Does our deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe and atop missiles on alert expose the weapons to additional risks that could be mitigated much cheaper and effectively by withdrawing and de-alerting the weapons?

Plan in Prague Speech Context

The nuclear investments forecast by the NNSA plan – combined with DOD modernization plans – should help undercut claims by (ultra)conservatives and uninformed that the New START treaty with Russia will somehow put the United States at a disadvantage.

Yet the massive investments to build weapons factories and modify warheads also raise questions about how the plan will be seen by the international community that is needed to support the Obama administration’s nonproliferation agenda. How will other nuclear weapon states interpret the plan and U.S. intensions, given that they need to be convinced to reduce, stop producing, and ultimately eliminate nuclear weapons to make nuclear reductions and eventually disarmament a reality?

In his Prague speech in April 2009, President Obama made a dual pledge: On the one hand, to “take concrete steps towards a world without nuclear weapons,” and to “put an end to Cold War thinking” by reducing “the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same.” On the other hand, he pledged to “maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies….” Whereas the president spoke of maintaining a nuclear deterrent, the NNSA plan speaks of “evolving and sustaining the nuclear deterrent.” (Emphasis added)

Likewise, while Congress during the past decade canceled or delayed, as NNSA describes them, “opportunities to exercise the full suite of design competencies through life extensions and modernizations” of nuclear weapons (presumably the Nuclear Robust Earth Penetrator and the Reliable Replacement Warhead), the new plan is designed for “providing the opportunity to fully exercise design and production skills” and “vastly improved capabilities” of modified warhead components.

The plan does echo the pledge to reduce the nuclear weapons stockpile, but that goal is conditioned on building new nuclear weapons production factories and creating a “more agile deterrent.” As the plan bluntly states, a “multi-year and steady investment in the modernization of the complex is an essential element of the NPR, allowing the United States to safely reduce the role of nuclear weapons.”

Striking a balance between disarmament and deterrence – a balance that conveys an clear transition towards disarmament – will be delicate and the administration must work to ensure that the goodwill of Prague is not undercut by nuclear modernizations.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

A military depot in central Belarus has recently been upgraded with additional security perimeters and an access point that indicate it could be intended for housing Russian nuclear warheads for Belarus’ Russia-supplied Iskander missile launchers.

The Indian government announced yesterday that it had conducted the first flight test of its Agni-5 ballistic missile “with Multiple Independently Targetable Re-Entry Vehicle (MIRV) technology.

While many are rightly concerned about Russia’s development of new nuclear-capable systems, fears of substantial nuclear increase may be overblown.

Despite modernization of Russian nuclear forces and warnings about an increase of especially shorter-range non-strategic warheads, we do not yet see such an increase as far as open sources indicate.